SOAS-AKS Working Papers in Korean Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Autonomous Power of the State

The autonomous power of the state : its origins, mechanisms and results Author(s): MICHAEL MANN Source: European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie, Vol. 25, No. 2, Tending the roots : nationalism and populism (1984), pp. 185-213 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23999270 Accessed: 14-09-2017 18:37 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie This content downloaded from 140.180.248.195 on Thu, 14 Sep 2017 18:37:47 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms MICHAEL MANN The autonomous power of the state , its origins, mechanisms and results This essay tries to specify the origins, mechanisms and results of the autonomous power which the state possesses in relation to the major power groupings of 'civil society'. The argument is couched generally, but it derives from a large, ongoing empirical research project into the development of power in human societ ies (i). At the moment, my generalisations are bolder about agrar ian societies ; concerning industrial societies I will be more tentative. -

Running Head: FAKE NEWS AS a THREAT to the DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT

Running head: FAKE NEWS AS A THREAT TO THE DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT Fake News as a Threat to the Democratic Media Environment: Past Conditions of Media Regulation and Their Contemporary Applicability to New Media in the United States of America and South Korea Jae Hyun Park Duke University FAKE NEWS AS A THREAT TO THE DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT 1 Abstract This study uses a comparative case study policy analysis to evaluate whether the media regulation standards that the governments of the United States of America and South Korea used in the past apply to fake news on social media and the Internet today. We first identify the shared conditions based on which the two governments intervened in the free press. Then, we examine media regulation laws regarding these conditions and review court cases in which they were utilized. In each section, we draw similarities and differences between the two governments’ courses of action. The comparative analysis will serve useful in the conclusion, where we assess the applicability of those conditions to fake news on new media platforms in each country and deliberate policy recommendations as well as policy flow between the two countries. Keywords: censorship, defamation, democracy, falsity, fairness, freedom of speech, intention, journalistic truth, news manipulation, objectivity FAKE NEWS AS A THREAT TO THE DEMOCRATIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 -

Candlelight Vigil at Chinese Embassy to Mark Save North Korea Refugees Day: September 24; Over 20 Cities Plan Action

For Immediate Release: September 21, 2015 Contact: Suzanne Scholte or Jack Rendler; Phone: 202-257-0095 (Scholte) or 612-202-8512 (Rendler) Candlelight Vigil at Chinese Embassy to Mark Save North Korea Refugees Day: September 24; Over 20 Cities Plan Action (Washington, D.C.)….On Thursday September 24, the North Korea Freedom Coalition joined by the International Coalition to Stop Crimes Against Humanity in North Korea is sponsoring the annual “Save North Korean Refugees Day" to recognize the horrifying plight and inhumane treatment of North Korean refugees by the Chinese government. Petition deliveries will occur in cities throughout the world including Washington, D.C., Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco; Seoul, Busan; Toyko; Berlin; London; The Hague; Toronto, Ottawa; Mexico City; Rio de Janeiro; Santiago; and Buenos Aires calling for the government of China to abide by its international treaty obligations and stop forcing North Koreans back to North Korea to face torture, imprisonment and even execution for fleeing their homeland. Solidarity cities including San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Waterloo, Ontario are planning events to call for action to help North Korean refugees. Several cities will also have events to mark the tragic circumstances facing North Korean refugees. For example, in Chicago, the North Korea Freedom Network will sponsor a protest at 11 am in front of the Chinese consulate, while in Washington, D.C., there will be a candlelight vigil at 8 pm at the Chinese embassy at which North Korean defectors and activists will read aloud the names of the hundreds of refugees who were forced back to North Korea by China. -

As Detained for 437 Days in China’S Sprawling New System of Incarceration and Indoctrination

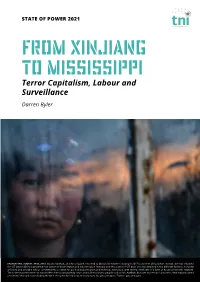

STATE OF POWER 2021 From Xinjiang to Mississippi Terror Capitalism, Labour and Surveillance Darren Byler KAZAKHSTAN, ALMATY, APRIL 2019: Gulzira Auelhan, an ethnic Kazakh, returned to China’s far western Xinjiang in 2017 to visit her ailing father. Instead, she was detained for 437 days in China’s sprawling new system of incarceration and indoctrination. Instead, over the course of 437 days, she was detained in five different facilities, including a factory and a middle school converted into a centre for political indoctrination and technical instruction, with several interludes of a form of house arrest with relatives. The Chinese government has said it offers free vocational education and skills training to people such as Ms. Auelhan. But over more than 14 months, “that training lasted one week,” she said, not including the time she spent forced to work in a factory. IG: @noorimages / Twitter: @noorimages The Chinese state within Xinjiang has forged a form of capitalist frontier-making based on data harvesting and unfree human labour that exploits ethno-racial difference in order to generate new forms of capital accumulation and coercive state power. ‘Where is your ID!’ the police contractor yelled at me in Uyghur. I looked up in surprise. I had been avoiding eye contact, trying to attract as little attention as possible. In April 2018, in the tourist areas of Kashgar – where there were checkpoints every 200 metres – the contractors usually recognised a bespectacled white person as a foreigner. But over the years that I had lived and worked as an anthropologist in Northwest China I had often been mistaken for a Uyghur. -

A Confucian Interpretation of South Korea's Candlelight Revolution

religions Article Candlelight for Our Country’s Right Name: A Confucian Interpretation of South Korea’s Candlelight Revolution Sungmoon Kim Department of Public Policy, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon, Hong Kong; [email protected]; Tel.: +(852)-3442-8274 Received: 10 September 2018; Accepted: 26 October 2018; Published: 28 October 2018 Abstract: The candlelight protest that took place in South Korea from October 2016 to March 2017 was a landmark political event, not least because it ultimately led to the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye. Arguably, its more historically important meaning lies in the fact that it marks the first nation-wide political struggle since the June Uprising of 1987, where civil society won an unequivocal victory over a regime that was found to be corrupt, unjust, and undemocratic, making it the most orderly, civil, and peaceful political revolution in modern Korean history. Despite a plethora of literature investigating the cause of what is now called “the Candlelight Revolution” and its implications for Korean democracy, less attention has been paid to the cultural motivation and moral discourse that galvanized Korean civil society. This paper captures the Korean civil society which resulted in the Candlelight Revolution in terms of Confucian democratic civil society, distinct from both liberal pluralist civil society and Confucian meritocratic civil society, and argues that Confucian democratic civil society can provide a useful conceptual tool by which to not only philosophically construct a vision of civil society that is culturally relevant and politically practicable but also to critically evaluate the politics of civil society in the East Asian context. -

An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida

Conductive Capacity of The State 1 Conductive Capacity of The State: An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida Initiative By Jose Pablo Olvera An Applied Research Project Submitted to the Department of Public Administration Texas State University-San Marcos In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Public Administration Spring 2017 Dr. Patricia Shields Christopher Brown, JD Ms. Alejandra Pena, MPA Conductive Capacity of The State 2 Abstract The purpose of this applied research paper is to conduct a preliminary assessment of Mexico’s political institutions since the Merida Initiative to evaluate the progress, or lack thereof, in relation to the agreement’s explicit goals of institutionalizing reforms and supporting democratic governance. The project’s framework is structured using three core pillar questions that address Mexican state capacities: coercive, extractive, and conductive capacity. Conductive capacity refers to the state’s ability to effectively channel citizen demands through the state apparatus. First, an assessment of Mexico’s political institutions is performed using a variety of methods, including data, survey-item, and case study analyses. Second, the dimension of conductive capacity is tested against coercive and extractive capacities to evaluate whether an interaction between these exists. The results of the assessment demonstrate that the Mexican state’s coercive and conductive capacities have significantly decreased since the implementation of the Merida Initiative, while demonstrating that coercive and extractive capacities of the state significantly predict conductive capacity dimension variables. Conductive Capacity of The State 3 Acknowledgments I would like to begin by thanking my parents, Alfonso and May, for their sacrifice made when they decided to leave almost everything behind so that my siblings and I could have a chance at a better future. -

Part I INTRODUCTION

Part I INTRODUCTION 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 1 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:380:30:38 PPMM 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 2 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:390:30:39 PPMM 1 Republics of the Possible State Building in Latin America and Spain Miguel A. Centeno and Agust í n E. Ferraro Introduction Latin American republics were among the fi rst modern political entities designed and built according to already tried and seemingly successful institutional mod- els. During the wars of independence and for several decades thereafter, pub- lic intellectuals, politicians, and concerned citizens willingly saw themselves confronted with a sort of void, a tabula rasa. Colonial public institutions and colonial ways of life had to be rejected, if possible eradicated, in order for new political forms and new social mores to be established in their stead. However, in contrast to the French or American revolutions, pure political utopias did not play a signifi cant role for Latin American institutional projects. The American Revolution was a deliberate experiment; the revolutionar- ies fi rmly believed that they were creating something new, something never attempted before. The French revolutionaries dramatically signaled the same purpose by starting a whole new offi cial calendar from year one. In contrast, Latin American patriots assumed that proven and desirable institutional mod- els already existed, and not just as utopic ideals. The models were precisely the state institutions of countries that had already undergone revolutions or achieved independence, or both: Britain , the United States, France, and others such as the Dutch Republic . -

Online Activism and South Korea's Candlelight Movement

WINDOW ON ASIA Candlelight rally in Seoul, June 2008. Online Activism PC: Michael-kay Park and South Korea’s @flickr.com. Candlelight Movement Hyejin KIM The Candlelight Movement of 2016 and outh Korea has a storied history of 2017 that successfully called for President mass agitation for political causes. Park Geun-hye to step down is among the SThe Candlelight Movement of 2016– largest social movements in South Korean 17, which called for President Park Geun-hye history. This movement attracted millions to step down, is among the largest—if not the of participants over a sustained period of largest—street demonstration in that history. time, while maintaining strikingly peaceful Set against any of several measuring sticks, demonstrations that ultimately achieved their it was a remarkable success. It attracted goal. In this essay, Hyejin Kim looks at the role millions of participants over a sustained of the Internet and new media in fostering a period of time. The events were strikingly new generation of activists and laying the peaceful—strangers smashed up against each foundation for a successful social mobilisation. other and encountered police, but participants prevented violence and there was not a single fatality. And, of course, the National Assembly 224 MADE IN CHINA YEARBOOK 2018 WINDOW ON ASIA eventually impeached the President, who was in a context where such views were taboo. later dismissed, tried in criminal court, and Surveys show that individual participation eventually sentenced to a lengthy prison term. declined when these organisations entered the Globally, examples like South Korea’s are fray (Kim 2008, 30). -

ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia

2014 ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia The Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions (ANNI) Compiled and Printed by Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) Secretariat of ANNI Editorial Committee: Balasingham Skanthakumar (Editor-in-chief) Joses Kuan Heewon Chun Layout: Prachoomthong Printing Group ISBN: 978-616-7733-06-7 Copyright ©2014 This book was written for the benefit of human rights defenders and may be quoted from or copied as long as the source and authors are acknowledged. Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) 66/2 Pan Road, Silom, Bang Rak Bangkok, 10500 Thailand Tel: +66 (0)2 637 91266-7 Fax: +66 (0)2 637 9128 Email: [email protected] Web: www.forum-asia.org Table of Contents Foreword 4 Regional Overview: Do NHRIs Occupy a Safe or Precarious Space? 6 Southeast Asia Burma: All the President’s Men 12 Indonesia: Lacking Effectiveness 25 Thailand: Protecting the State or the People? 34 Timor-Leste: Law and Practice Need Further Strengthening 45 South Asia Afghanistan: Unfulfilled Promises, Undermined Commitments 76 Bangladesh: Institutional Commitment Needed 89 The Maldives: Between a Rock and a Hard Place 108 Nepal: Missing Its Members 123 Sri Lanka: Protecting Human Rights or the Government? 135 Northeast Asia Hong Kong: Watchdog Institutions with Narrow Mandates 162 Japan: Government Opposes Establishing a National Institution 173 Mongolia: Selection Process Needed Fixing 182 South Korea: Silent and Inactive 195 Taiwan: Year of Turbulence 216 India: A Big Leap Forward 222 Foreword The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA), as the Secretariat of the Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions (ANNI), humbly presents the publication of the 2014 ANNI Report on the Performance and Establishment of National Human Rights Institutions in Asia. -

The Social Origins of State Power in China by Daniel Christopher

The Social Origins of State Power in China by Daniel Christopher Mattingly A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kevin J. O'Brien, Chair Professor Ruth Berins Collier Professor Peter L. Lorentzen Professor Noam Yuchtman Summer 2016 The Social Origins of State Power in China Copyright 2016 by Daniel Christopher Mattingly 1 Abstract The Social Origins of State Power in China by Daniel Christopher Mattingly Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Kevin J. O'Brien, Chair This dissertation investigates the origins of state power and political accountability. How do states exercise political control over their populations and implement policies that have clear winners and losers? Do democratic institutions in combination with a strong civil society strengthen political accountability? I examine these questions in the context of rural China, which combines limited local democracy and vibrant non-state groups such as kinship associations, temples, and neighborhood groups. Many argue that strong civil society institutions and local elections can curb the power of the state and hold government officials accountable. However, in this dissertation I argue that in China, strong civil society groups and village elections have expanded state power and helped officials confiscate wealth. The first part of the dissertation develops my theory of state power. Drawing on new data from rural China, I show that citizens distrust the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and believe that local party cadres do not represent their interests. -

Being a “Truth-Teller” in the Unsettled Period of Korean Journalism: a Case Study of Newstapa and Its Boundary Work

Being a “Truth-Teller” in the Unsettled Period of Korean Journalism: A Case Study of Newstapa and its Boundary Work A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Wooyeol Shin IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Giovanna Dell’Orto June 2016 © Wooyeol Shin, 2016 i Acknowledgements Completing this dissertation is a long journey. Faculty, friends, family members, and Newstapa journalists have helped me along the way. I would like to express my gratitude to these people for their support. Giovanna Dell’Orto has been an inspirational adviser to me throughout my graduate years. She is not just my academic adviser but also a truly good friend. She shows me how I can strive to be a good person in the highly stressful, competitive academic field. Without GD’s support, I would never survive in Murphy Hall. I am grateful to have Seth Lewis, Sid Bedingfield, and Jeffrey Broadbent as my dissertation committee members. Seth Lewis is a productive media sociologist and an encouraging reviewer. His research program has guided me to study the sociology of journalism, especially the boundary work of journalists in the changing media environment. Sid Bedingfield provides me with thoughtful feedback on how to extend my research on journalism further. Jeffrey Broadbent has been enormously generous to me. When I found out my outside committee member, he gradly agreed with a big smile, although I had never taken his class before. From him, I learned how to think and ask questions like a sociologist. His specialty of Asian studies, as well as of social movements, also helps me develop research ideas. -

Infrastructural Exclusion and the Fight for the City: Power, Democracy, and the Case of America’S Water Crisis

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLC\53-2\HLC208.txt unknown Seq: 1 29-OCT-18 9:18 Infrastructural Exclusion and the Fight for the City: Power, Democracy, and the Case of America’s Water Crisis K. Sabeel Rahman* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................. 533 I. INFRASTRUCTURAL EXCLUSION ............................ 536 R A. The Flint water crisis ................................ 536 R B. Mechanisms of infrastructural exclusion ............... 538 R II. TOWARD A POLITICAL THEORY OF INFRASTRUCTURE: POWER, DEMOCRACY, AND THE PUBLIC UTILITY TRADITION .......... 541 R III. CONSTRUCTING INCLUSIVE INFRASTRUCTURE: WATER AND BEYOND ................................................. 547 R A. Mandating water equity .............................. 548 R B. Restoring public (and democratic) utilities ............ 551 R C. Public oversight over the broader water infrastructure ....................................... 554 R 1. The importance of strategic and system-wide public oversight ........................................ 554 R 2. Institutionalizing strategic enforcement ............ 557 R IV. CONCLUSION ............................................ 560 R INTRODUCTION In 2013, government officials in Flint, Michigan, which had been placed under state-appointed emergency management following a long- standing budget crisis, imposed a variety of cost-cutting measures. One of these measures included switching the city’s water supply temporarily to the Flint River. Another decision was made not to spend scarce dollars on treat- ing the water with anti-corrosion agents. The result was a severe erosion of * Assistant Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School; Fellow, Roosevelt Institute. I am grateful to the editors of the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review for inviting me to contribute to this special issue. This paper was first drafted in December 2016. It draws on previous works including Rahman, THE NEW UTILITIES: PRIVATE POWER, SOCIAL INFRASTRUC- TURE, AND THE REVIVAL OF THE PUBLIC UTILITY CONCEPT, 30 CARDOZO L.