STATE CAPACITY AS POWER: a CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK Johannes Lindvall and Jan Teorell Lund University April 7, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Autonomous Power of the State

The autonomous power of the state : its origins, mechanisms and results Author(s): MICHAEL MANN Source: European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie, Vol. 25, No. 2, Tending the roots : nationalism and populism (1984), pp. 185-213 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23999270 Accessed: 14-09-2017 18:37 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv für Soziologie This content downloaded from 140.180.248.195 on Thu, 14 Sep 2017 18:37:47 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms MICHAEL MANN The autonomous power of the state , its origins, mechanisms and results This essay tries to specify the origins, mechanisms and results of the autonomous power which the state possesses in relation to the major power groupings of 'civil society'. The argument is couched generally, but it derives from a large, ongoing empirical research project into the development of power in human societ ies (i). At the moment, my generalisations are bolder about agrar ian societies ; concerning industrial societies I will be more tentative. -

As Detained for 437 Days in China’S Sprawling New System of Incarceration and Indoctrination

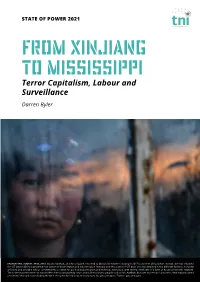

STATE OF POWER 2021 From Xinjiang to Mississippi Terror Capitalism, Labour and Surveillance Darren Byler KAZAKHSTAN, ALMATY, APRIL 2019: Gulzira Auelhan, an ethnic Kazakh, returned to China’s far western Xinjiang in 2017 to visit her ailing father. Instead, she was detained for 437 days in China’s sprawling new system of incarceration and indoctrination. Instead, over the course of 437 days, she was detained in five different facilities, including a factory and a middle school converted into a centre for political indoctrination and technical instruction, with several interludes of a form of house arrest with relatives. The Chinese government has said it offers free vocational education and skills training to people such as Ms. Auelhan. But over more than 14 months, “that training lasted one week,” she said, not including the time she spent forced to work in a factory. IG: @noorimages / Twitter: @noorimages The Chinese state within Xinjiang has forged a form of capitalist frontier-making based on data harvesting and unfree human labour that exploits ethno-racial difference in order to generate new forms of capital accumulation and coercive state power. ‘Where is your ID!’ the police contractor yelled at me in Uyghur. I looked up in surprise. I had been avoiding eye contact, trying to attract as little attention as possible. In April 2018, in the tourist areas of Kashgar – where there were checkpoints every 200 metres – the contractors usually recognised a bespectacled white person as a foreigner. But over the years that I had lived and worked as an anthropologist in Northwest China I had often been mistaken for a Uyghur. -

Competition and Cooperation

CONTRIBUTORS JAMES E. ALT is Frank G. Thomson Professor of Government and director of the Center of Basic Research in the Social Sciences at Harvard University. MARGARET LEVI is professor of political science and Harry Bridges Chair in Labor Studies, University of Washington, Seattle. She is also director of the University of Washington Center for Labor Studies. ELINOR OSTROM is codirector of the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis and the Center for the Study of Institutions, Population, and Environ- mental Change at Indiana University, Bloomington. She is also Arthur F. Bentley Professor of Political Science. KENNETH J. ARROW is Joan Kenney Professor of Economics Emeritus and profes- sor of Operations Research Emeritus at Stanford University. He is also director of the Stanford Center on Conflict and Negotiation. GARY S. BECKER is professor of economics and sociology at the University of Chicago. JAMES M. BUCHANAN is advisory general director of the Center for Study of Public Choice at George Mason University. NORMAN FROHLICH is professor of business administration at the University of Manitoba and senior researcher at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation. BARBARA GEDDES is associate professor of political science at the University of California at Los Angeles. ROBERT E. GOODIN is professor of philosophy in the Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. RUSSELL HARDIN is professor of politics at New York University. BRYAN D. JONES is professor of political science at the University of Washington, Seattle. ROBERT O. KEOHANE is James B. Duke Professor of Political Science at Duke University. xi xii Contributors DAVID D. -

Rewriting the Epic of America

One Rewriting the Epic of America IRA KATZNELSON “Is the traditional distinction between international relations and domes- tic politics dead?” Peter Gourevitch inquired at the start of his seminal 1978 article, “The Second Image Reversed.” His diagnosis—“perhaps”—was mo- tivated by the observation that while “we all understand that international politics and domestic structures affect each other,” the terms of trade across the domestic and international relations divide had been uneven: “reason- ing from international system to domestic structure” had been downplayed. Gourevitch’s review of the literature demonstrated that long-standing efforts by international relations scholars to trace the domestic roots of foreign pol- icy to the interplay of group interests, class dynamics, or national goals1 had not been matched by scholarship analyzing how domestic “structure itself derives from the exigencies of the international system.”2 Gourevitch counseled scholars to turn their attention to the international system as a cause as well as a consequence of domestic politics. He also cautioned that this reversal of the causal arrow must recognize that interna- tional forces exert pressures rather than determine outcomes. “The interna- tional system, be it in an economic or politico-military form, is underdeter- mining. The environment may exert strong pulls but short of actual occupation, some leeway in the response to that environment remains.”3 A decade later, Robert Putnam turned to two-level games to transcend the question as to “whether -

An Interview with Elinor Ostrom

Annual Reviews Conversations Presents An Interview with Elinor Ostrom Annual Reviews Conversations. 2010 Host: You are listening to an Annual Reviews prefatory interview. In Annual Reviews Conversations interviews are online this interview, Margaret Levi, editor of the Annual Review of Political at www.annualreviews.org/page/audio Science, talks with Elinor Ostrom. Professor Ostrom is the cofounder, Copyright © 2010 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved with her husband, Vincent Ostrom, and longtime codirector of the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis at Indiana University, and she now serves as its senior research director. She is currently the Arthur F. Bentley Professor of Political Science at Indiana University, as well as research professor and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity at Arizona State University. She is cowinner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. Margaret Levi: I have a couple questions that I am going to prime the pump with here, Lin, and then we can let conversation flow however it does. There are many things about your history and what you’ve done in your career that are immensely impressive and have broken all kinds of barriers. But one of the things that I’ve been most intrigued by, and which I know very few other people have achieved, is the way in which you have not only tolerated and encouraged a multiple-method 1 approach to how one does work, but how you’ve conquered so many different methods. You really are very au courant in just almost—first, you learned game theory, and you learned microeconomics. -

American Political Science Review

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW AMERICAN https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000060 . POLITICAL SCIENCE https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms REVIEW , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at 08 Oct 2021 at 13:45:36 , on May 2018, Volume 112, Issue 2 112, Volume May 2018, University of Athens . May 2018 Volume 112, Issue 2 Cambridge Core For further information about this journal https://www.cambridge.org/core ISSN: 0003-0554 please go to the journal website at: cambridge.org/apsr Downloaded from 00030554_112-2.indd 1 21/03/18 7:36 AM LEAD EDITOR Jennifer Gandhi Andreas Schedler Thomas König Emory University Centro de Investigación y Docencia University of Mannheim, Germany Claudine Gay Económicas, Mexico Harvard University Frank Schimmelfennig ASSOCIATE EDITORS John Gerring ETH Zürich, Switzerland Kenneth Benoit University of Texas, Austin Carsten Q. Schneider London School of Economics Sona N. Golder Central European University, and Political Science Pennsylvania State University Budapest, Hungary Thomas Bräuninger Ruth W. Grant Sanjay Seth University of Mannheim Duke University Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Sabine Carey Julia Gray Carl K. Y. Shaw University of Mannheim University of Pennsylvania Academia Sinica, Taiwan Leigh Jenco Mary Alice Haddad Betsy Sinclair London School of Economics Wesleyan University Washington University in St. Louis and Political Science Peter A. Hall Beth A. Simmons Benjamin Lauderdale Harvard University University of Pennsylvania London School of Economics Mary Hawkesworth Dan Slater and Political Science Rutgers University University of Chicago Ingo Rohlfi ng Gretchen Helmke Rune Slothuus University of Cologne University of Rochester Aarhus University, Denmark D. -

Rochester Phd Program in Political Science

Rochester PhD Program in Political Science Contents Introduction to the Program......................... 1 Main Fields of Study in Political Science American Politics............................... 5 Comparative Politics.......................... 6 Formal Political Theory...................... 7 International Relations....................... 8 Political Methodology......................... 9 Rochester Political Economy....................... 10 Selected Faculty Publications...................... 11 Rules & Requirements................................ 17 Timeline of Milestones................................ 28 Introduction to the Rochester PhD Program in Political Science Rigorous Analysis of Politics Introduction The Ph.D. program in Political Science at the University of Rochester is designed to train scholars to conduct rigorous analysis of politics at the highest level. Students learn the most advanced formal and statistical techniques to address substantive problems in political science, while some develop the technical skills needed to do work in pure formal theory or statistical methods, and others acquire skills for qualitative or historical work. The program has a storied history and long tradition of excellence. After joining Richard Fenno in Rochester in 1962, William Riker pushed the department – and the discipline – in a new direction, creating the field of “positive political theory,” which uses modeling techniques from mathematics, prob- ability theory, and game theory to study political phenomena of interest. To reflect -

An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida

Conductive Capacity of The State 1 Conductive Capacity of The State: An Assessment of Mexican Political Institutions Since the Merida Initiative By Jose Pablo Olvera An Applied Research Project Submitted to the Department of Public Administration Texas State University-San Marcos In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Public Administration Spring 2017 Dr. Patricia Shields Christopher Brown, JD Ms. Alejandra Pena, MPA Conductive Capacity of The State 2 Abstract The purpose of this applied research paper is to conduct a preliminary assessment of Mexico’s political institutions since the Merida Initiative to evaluate the progress, or lack thereof, in relation to the agreement’s explicit goals of institutionalizing reforms and supporting democratic governance. The project’s framework is structured using three core pillar questions that address Mexican state capacities: coercive, extractive, and conductive capacity. Conductive capacity refers to the state’s ability to effectively channel citizen demands through the state apparatus. First, an assessment of Mexico’s political institutions is performed using a variety of methods, including data, survey-item, and case study analyses. Second, the dimension of conductive capacity is tested against coercive and extractive capacities to evaluate whether an interaction between these exists. The results of the assessment demonstrate that the Mexican state’s coercive and conductive capacities have significantly decreased since the implementation of the Merida Initiative, while demonstrating that coercive and extractive capacities of the state significantly predict conductive capacity dimension variables. Conductive Capacity of The State 3 Acknowledgments I would like to begin by thanking my parents, Alfonso and May, for their sacrifice made when they decided to leave almost everything behind so that my siblings and I could have a chance at a better future. -

Part I INTRODUCTION

Part I INTRODUCTION 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 1 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:380:30:38 PPMM 99781107029866c01_p1-24.indd781107029866c01_p1-24.indd 2 110/9/20120/9/2012 110:30:390:30:39 PPMM 1 Republics of the Possible State Building in Latin America and Spain Miguel A. Centeno and Agust í n E. Ferraro Introduction Latin American republics were among the fi rst modern political entities designed and built according to already tried and seemingly successful institutional mod- els. During the wars of independence and for several decades thereafter, pub- lic intellectuals, politicians, and concerned citizens willingly saw themselves confronted with a sort of void, a tabula rasa. Colonial public institutions and colonial ways of life had to be rejected, if possible eradicated, in order for new political forms and new social mores to be established in their stead. However, in contrast to the French or American revolutions, pure political utopias did not play a signifi cant role for Latin American institutional projects. The American Revolution was a deliberate experiment; the revolutionar- ies fi rmly believed that they were creating something new, something never attempted before. The French revolutionaries dramatically signaled the same purpose by starting a whole new offi cial calendar from year one. In contrast, Latin American patriots assumed that proven and desirable institutional mod- els already existed, and not just as utopic ideals. The models were precisely the state institutions of countries that had already undergone revolutions or achieved independence, or both: Britain , the United States, France, and others such as the Dutch Republic . -

Government 601: Methods of Political Analysis I Fall 2003, Tueday 7:00–10:00P (WE 104)

Government 601: Methods of Political Analysis I Fall 2003, Tueday 7:00–10:00p (WE 104) Professors: Walter R. Mebane, Jr. Jonas Pontusson 217 White Hall 205 White Hall 255-3868 255-6764 [email protected] [email protected] office hours: T 3–5, W 2–3 office hours: MW 10–11 Assignment Due Dates due date description TBA one weekly discussion paper as assigned (weeks 3–10, 12) October 28 “explanations” paper November 11 research pre-proposal November 18 Boolean exercise December 15 research proposal Reading Availability We will be reading large proportions of most of the following books, and most are worth having on the shelf, so you may want to buy them. On the other hand, several are expensive. Most of the books should also soon appear on reserve in the Government Reading Room in Olin (room 405). Photocopies of other required reading should also be available in the Reading Room. Browning, Christopher R. 2000. Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers. New York: Cam- bridge UP. Browning, Christopher R. 1998. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York: HarperCollins. Campbell, Donald T., and Julian C. Stanley. 1966. Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs for Research. Chicago: Rand McNally. Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. 1996. Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holo- caust. New York: Knopf. Golden, Miriam. 1997. Heroic Defeats. New York: Cambridge UP. Hedstr¨om,Peter, and Richard Swedborg, eds. 1998. Social Mechanisms: An Analytical Approach to Social Theory. New York: Cambridge UP. King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane and Sidney Verba. -

APSA Contributors AS of NOVEMBER 10, 2014

APSA Contributors AS OF NOVEMBER 10, 2014 This list celebrates the generous contributions of our members in Jacobson Paul Allen Beck giving to one or more of the following programs from 1996 through 2014: APSA awards, programs, the Congressional Fellowship Pro- Cynthia McClintock John F. Bibby gram, and the Centennial Campaign. APSA thanks these donors for Ruth P. Morgan Amy B. Bridges ensuring that the benefi ts of membership and the infl uence of the Norman J. Ornstein Michael A. Brintnall profession will extend far into the future. APSA will update and print T.J. Pempel David S. Broder this list annually in the January issue of PS. Dianne M. Pinderhughes Charles S. Bullock III Jewel L. Prestage Margaret Cawley CENTENNIAL CIRCLE Offi ce of the President Lucian W. Pye Philip E. Converse ($25,000+) Policy Studies Organization J. Austin Ranney William J. Daniels Walter E. Beach Robert D. Putnam Ben F. Reeves Christopher J. Deering Doris A. Graber Ronald J Schmidt, Sr. Paul J. Rich Jorge I. Dominguez Pendleton Herring Smith College David B. Robertson Marion E. Doro Chun-tu Hsueh Endowment Janet D. Steiger for International Scholars Catherine E. Rudder Melvin J. Dubnick and Huang Hsing Kay Lehman Schlozman Eastern Michigan University Foundation FOUNDER’S CIRCLE ($5,000+) Eric J. Scott Leon D. Epstein Arend Lijphart Tony Affi gne J. Merrill Shanks Kathleen A. Frankovic Elinor Ostrom Barbara B. Bardes Lee Sigelman John Armando Garcia Beryl A. Radin Lucius J. Barker Howard J. Silver George J. Graham Leo A. Shifrin Robert H. Bates William O. Slayman Virginia H. -

The Analytical Narrative Project

The Analytical Narrative Project The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bates, Robert H., Avner Greif, Margaret Levi, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, and Barry R. Weingast. 2000. The Analytical Narrative Project. American Political Science Review 94(3): 696-702. Published Version http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2585843 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3710302 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Analytic Narratives September 2000 TheAnalytic Narrative Project ROBERT H. BATES Harvard University AVNER GREIF Stanford University MARGARET LEVI Universityof Washington JEAN-LAURENT ROSENTHAL Universityof California, Los Angeles BARRY R. WEINGAST Stanford University In Analytic Narratives,we attempt to address several bounded rationality. We believe that each of these issues. First, many of us are engaged in in-depth perspectives brings something of value, and to different case studies, but we also seek to contribute to, and degrees the essays in our book represent an integration to make use of, theory. How might we best proceed? of perspectives. By explicitly outlining an approach that Second, the historian, the anthropologist, and the area relies on rational choice and mathematical models, we specialist possess knowledge of a place and time. They do not mean to imply that other approaches lack rigor have an understanding of the particular.