Comparative Politics. the Core Reading List Is NOT Meant to Be Exhaustive Or to Substitute for Taking Seminars with CP Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

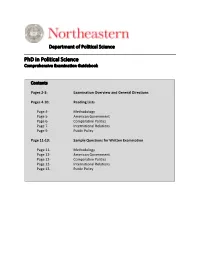

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Review Article the MANY VOICES of POLITICAL CULTURE Assessing Different Approaches

Review Article THE MANY VOICES OF POLITICAL CULTURE Assessing Different Approaches By RICHARD W. WILSON Richard J. Ellis and Michael Thompson, eds. Culture Matters: Essays in Honor of Aaron Wildavsky. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1997, 252 pp. Michael Gross. Ethics and Activism: The Theory and Practice of Political Moral- ity. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997, 305 pp. Samuel P. Huntington. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996, 367 pp. Ronald Inglehart. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in Forty-three Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997, 453 pp. David I. Kertzer. Politics and Symbols:The Italian Communist Party and the Fall of Communism. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996, 211 pp. HE popularity of political culture has waxed and waned, yet it re- Tmains an enduring feature of political studies. In recent years the appearance of many excellent books and articles has reminded us of the timeless appeal of the subject and of the need in political analysis to ac- count for values and beliefs. To what extent, though, does the current batch of studies in political culture suffer from the difficulties that plagued those of an earlier time? The recent resurgence of interest in political culture suggests the importance of assessing the relative merits of the different approaches that theorists employ. ESTABLISHING EVALUATIVE CRITERIA The earliest definitions of political culture noted the embedding of po- litical systems in sets of meanings and purposes, specifically in symbols, myths, beliefs, and values.1 Pye later enlarged upon this theme, stating 1 Sidney Verba, “Comparative Political Culture,” in Lucian W. -

Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics of Social Solidarity

Kathleen Thelen Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics XXI (73) - 2015 of Social Solidarity 2014. Cambridge University Press. Pages: 251 ISBN: 9781107679566 Are notions of solidarity obsolete in the face of the free market? Is there a single developed capitalism or are there many? Is there a best, most efficient way to delimit the state from the market and the public from the private or are there alternative, equally efficient solutions? Comparative political economy is often based on the premise that the latter is true. In particular, the now classic Varieties of Capitalism (VofC) comparative approach postulates two types of institutional frameworks. The general idea was that each institutional solution generates positive externalities which may or may not be captured by specific solutions in other institutional domains. Therefore, the precondition for economic success of any given country is not any single institutional solution, but rather a consistent approach throughout the political economy cutting through finance, labor markets, education, inter-firm relations etc. The analysis of developed countries revealed two principal types of such institutional consistency – the coordinated market economy (CME) as a more restrictively regulated variety of capitalism and the liberal market economy (LME) as a more flexible variety oriented towards free markets. The CME path to efficiency and growth is based on the formation of specific skills, protected and organized labor markets and long-term bank-centric corporate governance systems. This was considered as an approach of the Scandinavian countries, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Japan. On the other hand, LME countries base their institutional comparative advantage on general skill formation, flexible labor markets with low unionization and short-term oriented corporate governance with predominant stock-market financing. -

Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism and Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change* by Vivien A

Center for European Studies Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper Series 07.3 (2007) Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism * And Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change by Vivien A. Schmidt Jean Monnet Professor of European Integration Department of International Relations, Boston University 152 Bay State Road, Boston MA 02215 Tel: 1 617 3580192; Fax: 1 617 3539290 Email: [email protected] Abstract The Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) literature’s difficulties in accounting for the full diversity of na- tional capitalisms and in explaining institutional change result at least in part from its tendency to downplay state action and from its rather static, binary division of capitalism into two overall systems. This paper argues first of all that by taking state action—used as shorthand for govern- ment policy forged by the political interactions of public and private actors in given institutional contexts—as a significant factor, national capitalisms can be seen to come in at least three varie- ties: liberal, coordinated, and state-influenced market economies. But more importantly, by bring- ing the state back in, we also put the political back into political economy—in terms of policies, political institutional structures, and politics. Secondly, the paper shows that although recent re- visions to VoC that account for change by invoking open systems or historical institutionalist in- *Paper prepared for presentation for the panel: 7-5 “Explaining institutional change in different varieties of capitalism,” of the Annual Meetings of the American Political Science Association (Philadelphia PA, Aug. 31-Sept. 3, 2006). -

Competition and Cooperation

CONTRIBUTORS JAMES E. ALT is Frank G. Thomson Professor of Government and director of the Center of Basic Research in the Social Sciences at Harvard University. MARGARET LEVI is professor of political science and Harry Bridges Chair in Labor Studies, University of Washington, Seattle. She is also director of the University of Washington Center for Labor Studies. ELINOR OSTROM is codirector of the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis and the Center for the Study of Institutions, Population, and Environ- mental Change at Indiana University, Bloomington. She is also Arthur F. Bentley Professor of Political Science. KENNETH J. ARROW is Joan Kenney Professor of Economics Emeritus and profes- sor of Operations Research Emeritus at Stanford University. He is also director of the Stanford Center on Conflict and Negotiation. GARY S. BECKER is professor of economics and sociology at the University of Chicago. JAMES M. BUCHANAN is advisory general director of the Center for Study of Public Choice at George Mason University. NORMAN FROHLICH is professor of business administration at the University of Manitoba and senior researcher at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation. BARBARA GEDDES is associate professor of political science at the University of California at Los Angeles. ROBERT E. GOODIN is professor of philosophy in the Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. RUSSELL HARDIN is professor of politics at New York University. BRYAN D. JONES is professor of political science at the University of Washington, Seattle. ROBERT O. KEOHANE is James B. Duke Professor of Political Science at Duke University. xi xii Contributors DAVID D. -

Coming in the NEXT ISSUE

Association News contributors to the international scientific DBASSE can be accessed at http://sites. community. Nearly 500 members of the nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/index. Coming NAS have won Nobel Prizes” (See http:// htm. Presiding over DBASSE presently nasonline.org/about-nas/mission). is political scientist Kenneth Prewitt. in the For the past century and a half, mem- Scholars who are not NAS members also NEXT bers have investigated and responded to regularly participate as members of NAS questions posed by our national leaders committees, and we urge all political sci- ISSUE as a form of service to the nation without entists to give serious consideration to financial recompense. As Ralph Cicerone, these requests. A preview of some of the articles in the president of the NAS, never fails to relate The discussion at this year’s meeting April 2014 issue: to new members at the annual installation of NAS-member political scientists at ceremony, while our advice is often solic- the APSA convention centered on how to SYMPOSIUM ited—its first report to the Lincoln admin- effectively transmit the best social science US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION istration addressed whether our country knowledge to the government through FORECASTING should adopt the metric system, and sent the NRC. One issue facing the NRC in Michael Lewis-Beck and back a consensus “yes” answer—this ad- general and the DBASSE in particular Mary Stegmaier, guest editors vice is not always followed. Scientific is that by charter the NAS is not permit- FEATURES objectivity is the goal of the Academy, not ted to solicit contracts from government political advocacy. -

Rewriting the Epic of America

One Rewriting the Epic of America IRA KATZNELSON “Is the traditional distinction between international relations and domes- tic politics dead?” Peter Gourevitch inquired at the start of his seminal 1978 article, “The Second Image Reversed.” His diagnosis—“perhaps”—was mo- tivated by the observation that while “we all understand that international politics and domestic structures affect each other,” the terms of trade across the domestic and international relations divide had been uneven: “reason- ing from international system to domestic structure” had been downplayed. Gourevitch’s review of the literature demonstrated that long-standing efforts by international relations scholars to trace the domestic roots of foreign pol- icy to the interplay of group interests, class dynamics, or national goals1 had not been matched by scholarship analyzing how domestic “structure itself derives from the exigencies of the international system.”2 Gourevitch counseled scholars to turn their attention to the international system as a cause as well as a consequence of domestic politics. He also cautioned that this reversal of the causal arrow must recognize that interna- tional forces exert pressures rather than determine outcomes. “The interna- tional system, be it in an economic or politico-military form, is underdeter- mining. The environment may exert strong pulls but short of actual occupation, some leeway in the response to that environment remains.”3 A decade later, Robert Putnam turned to two-level games to transcend the question as to “whether -

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010

Government 2010. Strategies of Political Inquiry, G2010 Gary King, Robert Putnam, and Sidney Verba Thursdays 12-2pm, Littauer M-17 Gary King [email protected], http://GKing.Harvard.edu Phone: 617-495-2027 Office: 34 Kirkland Street Robert Putnam [email protected] Phone: 617-495-0539 Office: 79 JFK Street, T376 Sidney Verba [email protected] Phone: 617-495-4421 Office: Littauer Center, M18 Prerequisite or corequisite: Gov1000 Overview If you could learn only one thing in graduate school, it should be how to do scholarly research. You should be able to assess the state of a scholarly literature, identify interesting questions, formulate strategies for answering them, have the methodological tools with which to conduct the research, and understand how to write up the results so they can be published. Although most graduate level courses address these issues indirectly, we provide an explicit analysis of each. We do this in the context of a variety of strategies of empirical political inquiry. Our examples cover American politics, international relations, compara- tive politics, and other subfields of political science that rely on empirical evidence. We do not address certain research in political theory for which empirical evidence is not central, but our methodological emphases will be as varied as our substantive examples. We take empirical evidence to be historical, quantitative, or anthropological. Specific methodolo- gies include survey research, experiments, non-experiments, intensive interviews, statistical analyses, case studies, and participant observation. Assignments Weekly reading assignments are listed below. Since our classes are largely participatory, be sure to complete the readings prior to the class for which they are as- signed. -

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT and Permanent External Scientific Member, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, Germany Address Department of Political Science [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology http://web.mit.edu/polisci/faculty/K.Thelen.html 77 Massachusetts Avenue, E53-470 Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 Education M.A. (1981) and Ph.D. (1987), Political Science, University of California, Berkeley B.A. (1979), Political Science, University of Kansas (university and department honors) Teaching Positions Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT (2009-present) Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2005-2009) Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2004-2005) Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University (1994-2004) Assistant Professor, Department of Politics, Princeton University, 1988-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Oberlin College, 1987-1988 Other Appointments and Invited Visiting Positions 2012- 2014 Research Fellow, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung April 2013: Guest scholar, Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden Summer 2011: Guest scholar, Institute for Advanced Study Berlin (Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin) and Science Center (Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung) Summer 2010: Visiting Professor, Sciences Po, Paris 2007-2011: Senior Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford University, Oxford UK -

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Oxford Handbooks Online Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Julia Lynch and Martin Rhodes The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism Edited by Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia G. Falleti, and Adam Sheingate Print Publication Date: Mar 2016 Subject: Political Science, Comparative Politics, Political Institutions Online Publication Date: May 2016 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199662814.013.25 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines how historical institutionalism has influenced the analysis of welfare state and labor market policies in the rich industrial democracies. Using Lakatos’s concept of the “scientific research program” as a heuristic, the authors explore the development and expansion of historical institutionalism as a predominant approach in welfare state research. Focusing on this tradition’s strong core of actors (academic path- and boundary-setters), rules (methodology and methods), and norms (ontological and epistemological assumptions), they strive to demarcate the terrain of HI within studies of the welfare state, and to reveal the capacity of HI in this field to underpin a robust but flexible and enduring scholarly research program. Keywords: welfare state, Lakatos, research program, historical institutionalism, ideational approaches HISTORICAL institutionalism and the analysis of welfare states (including the ancillary policy domain of the labor market) overlap significantly. More than elsewhere in Political Science and public policy, much single-country, program, and comparative analysis of the welfare state since the 1980s has taken an historical approach (Amenta 2003). Relatedly, some of the major welfare state scholars have also been major historical institutionalism theorists and proponents—most prominently, but not only, Theda Skocpol, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen. -

An Interview with Elinor Ostrom

Annual Reviews Conversations Presents An Interview with Elinor Ostrom Annual Reviews Conversations. 2010 Host: You are listening to an Annual Reviews prefatory interview. In Annual Reviews Conversations interviews are online this interview, Margaret Levi, editor of the Annual Review of Political at www.annualreviews.org/page/audio Science, talks with Elinor Ostrom. Professor Ostrom is the cofounder, Copyright © 2010 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved with her husband, Vincent Ostrom, and longtime codirector of the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis at Indiana University, and she now serves as its senior research director. She is currently the Arthur F. Bentley Professor of Political Science at Indiana University, as well as research professor and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity at Arizona State University. She is cowinner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. Margaret Levi: I have a couple questions that I am going to prime the pump with here, Lin, and then we can let conversation flow however it does. There are many things about your history and what you’ve done in your career that are immensely impressive and have broken all kinds of barriers. But one of the things that I’ve been most intrigued by, and which I know very few other people have achieved, is the way in which you have not only tolerated and encouraged a multiple-method 1 approach to how one does work, but how you’ve conquered so many different methods. You really are very au courant in just almost—first, you learned game theory, and you learned microeconomics.