CSG Journal 2020-21REV4-CALIBRI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Forestry in Belgium Since the End of the Eighteenth Century

/ CHAPTER 3 State Forestry in Belgium since the End of the Eighteenth Century Pierre-Alain Tallier, Hilde Verboven, Kris Vandekerkhove, Hans Baeté and Kris Verheyen Forests are a key element in the structure of the landscape. Today they cover about 692,916 hectares, or about 22.7 per cent of Belgium. Unevenly distributed over the country, they constitute one of Belgium’s rare natural resources. For centuries, people have shaped these forests according to their needs and interests, resulting in the creation of man- aged forests with, to a greater or lesser extent, altered structure and species composition. Belgian forests have a long history in this respect. For millennia, they have served as a hideout, a place of worship, a food storage area and a material reserve for our ancestors. Our predecessors not only found part of their food supply in forests, but used the avail- able resources (herbs, leaves, brooms, heathers, beechnuts, acorns, etc.) to feed and to make their flocks of cows, goats and sheep prosper. Above all, forests have provided people with wood – a natural and renewable resource. As in many countries, depending on the available trees and technological evolutions, wood products have been used in various and multiple ways, such as heating and cooking (firewood, later on charcoal), making agricultural implements and fences (farmwood), and constructing and maintaining roads. Forests delivered huge quan- tities of wood for fortification, construction and furnishing, pit props, naval construction, coaches and carriages, and much more. Wood remained a basic material for industrial production up until the begin- ning of the nineteenth century, when it was increasingly replaced by iron, concrete, plastic and other synthetic materials. -

We Honour the Pouring Tradition…

Beer iis to Bellgiium as wiine iis to France and whiisky iis to Scotlland. Bellgiians can choose from over 800 diifferent brews from around 100 breweriies. These breweriies are known for theiir perfect ballance of hiigh qualliity, advanced bllendiing methods and state of the art technollogy. The resullts are here for you to enjoy. We honour the pouring tradition… I The Purification, your bartender will always use a clean glass, which is rinsed and then chilled with cold water, allowing the glass to reach the same temperature as the beer. II The Sacrifice, ensuring every drop of beer is fresh, your bartender allows the first foams from the tap to wash away. III The Liquid Alchemy Begins, the chalice is held at 45 degree angle allowing the perfect amount of foam to start forming the head of the beer. IV The Head, the glass is straightened and the head forms creating the vital protection for the beer ensuring maximum freshness and flavour. V The Removal, your bartender then closes the tap in one swift motion and moves the glass away to prevent drips entering the beer that have had contact with the air, these drops have oxidized and are not worthy of your beer. VI The Beheading, while the head is still forming, your bartender cuts it gently with a knife to eliminate the larger bubbles, bursting easily they accelerate the dissipation of the head. VII The Cleansing, your bartender rinses the bottom and sides of your glass, this keeps the outside of the chalice clean and comfortable to hold. -

Sectorverdeling Planning En Kwaliteit Ouderenzorg Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen

Sectorverdeling planning en kwaliteit ouderenzorg provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Karolien Rottiers: arrondissementen Dendermonde - Eeklo Toon Haezaert: arrondissement Gent Karen Jutten: arrondissementen Sint-Niklaas - Aalst - Oudenaarde Gemeente Arrondissement Sectorverantwoordelijke Aalst Aalst Karen Jutten Aalter Gent Toon Haezaert Assenede Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Berlare Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Beveren Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Brakel Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Buggenhout Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers De Pinte Gent Toon Haezaert Deinze Gent Toon Haezaert Denderleeuw Aalst Karen Jutten Dendermonde Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Destelbergen Gent Toon Haezaert Eeklo Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Erpe-Mere Aalst Karen Jutten Evergem Gent Toon Haezaert Gavere Gent Toon Haezaert Gent Gent Toon Haezaert Geraardsbergen Aalst Karen Jutten Haaltert Aalst Karen Jutten Hamme Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Herzele Aalst Karen Jutten Horebeke Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Kaprijke Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Kluisbergen Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Knesselare Gent Toon Haezaert Kruibeke Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Kruishoutem Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Laarne Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Lebbeke Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Lede Aalst Karen Jutten Lierde Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Lochristi Gent Toon Haezaert Lokeren Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Lovendegem Gent Toon Haezaert Maarkedal Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Maldegem Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Melle Gent Toon Haezaert Merelbeke Gent Toon Haezaert Moerbeke-Waas Gent Toon Haezaert Nazareth Gent Toon Haezaert Nevele Gent Toon Haezaert -

Appendix 1: Monastic and Religious Foundations in Thirteenth-Centur Y

APPENDIX 1: MONASTIC AND RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FLANDERS AND HAINAUT Affiliation: Arrouaise Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Eeckhout c. 1060/1146 Arrouaise Men Choques 1120/1138 Arrouaise Men Cysoing 855/1132 Arrouaise Men Phalernpin 1039/1145 Arrouaise Men Saint-Jean Baptiste c. 680/1142 Arrouaise Men Saint-Ni colas des Pres 1125/1140 Arrouaise Men Warneton 1066/1142 Arrouaise Men Zoetendale 1162/1215 re-founded Men Zonnebeke 1072/1142 Arrouaise Men Affiliation: Augustinian Canons Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Saint-Aubert 963/1066 reforrned Men Saint-Marie, Voormezele 1069/1110 reforrned Men Saint-Martin, Ypres 1012/1102 reformed Men Saint-Pierre de Loo c. 1050/1093 reformed Men Saint-Pierre et Saint-Vaast c. 1091 Men Affiliation: Beguines Name Date cf Foundation MenlWomen Aardenburg 1249 Wornen Audenarde 1272 Wornen Bardonck, Y pres 1271/1273 Wornen Bergues 1259 Wornen 118 WOMEN, POWER, AND RELIGIOUS PATRONAGE Binehe 1248 Wornen Briel, Y pres 1240 Wornen Carnbrai 1233 Wornen Charnpfleury, Douai 1251 Wornen Damme 1259 Wornen Deinze 1273 Wornen Diksrnuide 1273 Wornen Ijzendijke 1276 Wornen Maubeuge 1273 Wornen Cantirnpre, Mons 1245 Wornen Orehies 1267 Wornen Portaaker (Ghent) 1273 Wornen Quesnoy 1246 Wornen Saint-Aubert (Bruges) 1270 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Courtrai) 1242 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Ghent) 1234 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Lilie) 1244/1245 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Valeneiennes) 1239 Wornen Ter Hooie (Ghent) 1262 Wornen Tournai 1241 Wornen Wetz (Douai) 1245 Wornen Wijngaard (Bruges) 1242 Wornen Affiliation: Benedictine Name Date oJ Foundation Men/Women Anehin 1079 Men Notre-Darne d'Avesnes 1028 Wornen Bergues Saint-Winoe 1028 Men Bourbourg c. 1099 Wornen Notre-Darne de Conde e. -

Daguitstappen in Oost-Vlaanderen Verklaring Iconen Gratis

gratis & betaalbare daguitstappen in Oost-Vlaanderen Verklaring iconen gratis parkeren & betaalbare picknick daguitstappen eten en drinken in Oost-Vlaanderen speeltuin toegankelijk voor rolstoelgebruikers Deze brochure bundelt het gratis of op z’n minst betaalbaar vrijetijdsaanbod van het Provinciebestuur. Een reisgids die het mogelijk maakt om een uitstap naar een provinciaal uitstap naar natuur en bos domein, centrum of erfgoedsite te plannen. uitstappen met sport en doe-activiteiten De brochure laat je toe om in te schatten hoeveel een daguitstap naar een provinciaal domein of erfgoedsite kost. culturele uitstap Maar ook of het domein vlot bereikbaar is met de auto, het openbaar vervoer of voor personen met een beperking. De brochure is geschreven in vlot leesbare taal. De Provincie stapt af van de typische ambtenarentaal en ruilt lange teksten in voor symbolen, foto's of opsommingen. Op die manier maakt de Provincie vrije tijd en vakantie toegankelijk voor iedereen! 1 Aarzel dus niet om een kijkje te nemen in deze brochure en ontdek ons mooi aanbod. Colofon Deze publicatie is een initiatief van de directie Wonen en Mondiale Solidariteit van het Provinciebestuur Oost-Vlaanderen en het resultaat van een vruchtbare samenwerking tussen de dienst Communicatie, dienst Mobiliteit, directie Sport & Recreatie, directie Leefmilieu, directie Economie, directie Erfgoed en Toerisme Oost-Vlaanderen. Samenstelling Eindredactie: directie Wonen en Mondiale Solidariteit: Laurence Boelens, Melissa Van den Berghe en David Talloen Vormgeving: dienst Communicatie Uitgegeven door de deputatie van de Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen. Beleidsverantwoordelijke: gedeputeerde Leentje Grillaert Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Leentje Grillaert, gedeputeerde, p/a Gouvernementstraat 1, 9000 Gent Juni 2019 D/2019/5319/5 #maakhetmee Waar in Oost-Vlaanderen? Inhoud Hoe lees je de brochure? ..................................................................................................................................................................................... -

De Versterkingen Van De Wellingtonbarriere' in Oost-Vlaanderen

DE VERSTERKINGEN VAN DE WELLINGTONBARRIERE' IN OOST-VLAANDEREN DE VESTING DENDERMONDE, DE GENTSE CITADEL EN DE VESTING OUDENAARDE ROBERT GILS GENT 2005 DE VERSTERKINGEN VAN DE WELLINGTONBARRIERE' IN OOST-VLAANDEREN DE VEST! G DENDERMONDE, DE GE TSE CITA DEL EN DE VESTING OUDENAARDE ROBERT GILS GENT 2005 INLEIDING Wanneer Napoleon in 1815 van het toneel verdwijnt, lijkt er voor Ew·opa een nieuwe tijd aan te bi-eken. De grote mo gendheden nemen het besluit de beide Nederlanden te vei- enigen onder het Huis van Oranje. Tussen 1815 en 18l0, tijdens die kortstondige hereniging, bouwt of vernieuwt de ederla.ndse genie, op het grond gebied van het huidige België, 19 vestingen als grensverde diging tegen Frankrijk: de Wellingronbarrière. Drie van die vestingen lagen op het grondgebied van de provincie Oost Vlaanderen, namelijk Dendern10nde, Gent en Oudenaarde. Deze publicatie schetst de tomandkom.i.ngvan de Welling ton barrière en beschrijft de ,-ersterkingen van die drie Oost-Vlaamse steden, alsook de vestingbouwkundige over blijfselen ervan. DE WELLINGTON ' BARRIERE EEN BARRIÈ RE Grensversrerkingen behoorden tot de zogenaamde strate gische versterkingen. Ze moesten nier alleen een object ver dedigen, zoals een woning of een nederzetting, maar een hele streek of zelfs een land en maakten dus deel uit van de nationale landsverdediging. De uitbouw van dergelijke ,·er srerkingen was maar mogelijk wanneer her centraal bestuur sterk genoeg was om zijn wil op re leggen, zoals dar het geval was voor de Romeinen, de graven van Vlaanderen of Ka.rel V. Grensversrerkingen bestonden uit één of meerdere lij nen van forten of vestingen (dit zijn versterkte steden), uit verdedigingslinies of uit een combinatie van beide voor gaande. -

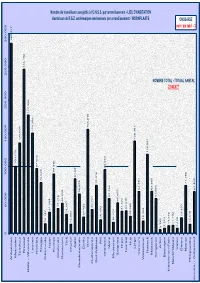

Nombre De Travailleurs Assujettis À L'o.N.S.S. Par Arrondissement - LIEU D'habitation Aantal Aan De R.S.Z

0 50.000 100.000 150.000 200.000 250.000 300.000 Antwerpen 285.317 Mechelen 100.713 Turnhout 135.601 Brussel 246.196 Halle - Vilvoorde 177.566 Leuven 150.259 Nivelles 97.005 Brugge 76.029 Diksmuide 14.147 Ieper 31.594 Nombre detravailleursassujettisàl'O.N.S.S.pararrondissement-LIEUD'HABITATION Aantal aandeR.S.Z.onderworpenwerknemersperarrondissement-WOONPLAATS Kortrijk 89.016 Oostende 37.216 Roeselare 45.028 Tielt 28.247 Veurne 13.584 Aalst 81.681 Dendermonde 58.979 Eeklo 24.422 Gent 156.016 Oudenaarde 35.701 Sint-Niklaas 72.016 Ath 20.100 Charleroi 95.653 Mons 52.166 Mouscron 16.414 Soignies 45.607 Thuin 32.872 Tournai 33.570 Huy 25.280 Liège 138.301 Verviers 62.751 Waremme 18.308 Hasselt 118.531 Maaseik 62.885 NOMBRE TOTAL-TOTAALAANTAL Tongeren 51.994 Arlon 5.369 Bastogne 7.373 Marche-en-Fam 11.275 2.945.077 Neufchâteau 11.792 voir /zietabI-3 Virton 7.419 ONSS-RSZ Dinant 23.320 Namur 71.786 Philippeville 13.519 Inconnu / Onbekend 62.459 0 100.000 200.000 300.000 400.000 500.000 600.000 700.000 800.000 Antwerpen 372.354 Mechelen 80.255 Turnhout 113.531 Brussel 720.477 Halle - Vilvoorde 179.132 Leuven 101.940 Nivelles 71.474 Brugge 66.492 Diksmuide 8.232 22.337 Ieper Nombre detravailleursassujettisàl'O.N.S.S.pararrondissement-LIEUDETRAVAIL Aantal aandeR.S.Z.onderworpenwerknemersperarrondissement-WERKPLAATS Kortrijk 89.877 Oostende 23.727 Roeselare 48.038 Tielt 26.045 Veurne 11.669 Aalst 38.850 Dendermonde 29.849 Eeklo 10.773 Gent 148.949 Oudenaarde 24.309 Sint-Niklaas 45.822 Ath 10.225 Charleroi 84.326 Mons 32.591 Mouscron 18.774 Soignies -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

The Black Death and Recurring Plague During the Late Middle Ages in the County of Hainaut

The Black Death and recurring plague during the late Middle Ages in the County of Hainaut Joris Roosen BinnenwerkJorisVersie2.indd 1 21/09/2020 15:45:13 Colofon The Black Death and recurring plague during the late Middle Ages in the County of Hainaut: Differential impact and diverging recovery ISBN: 978-94-6416-146-5 Copyright © 2020 Joris Roosen All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any way or by any means without the prior permission of the author, or when applicable, of the publishers of the scientific papers. Layout: Vera van Ommeren, persoonlijkproefschrift.nl Printing: Ridderprint | www.ridderprint.nl Dit proefschrift werd mogelijk gemaakt met financiële steun van de European Research Council (binnen het project “COORDINATINGforLIFE, beursnummer 339647, binnen het kader van het financieringsprogramma FP7-IDEAS-ERC) BinnenwerkJorisVersie2.indd 2 21/09/2020 15:45:13 The Black Death and recurring plague during the late Middle Ages in the County of Hainaut Differential impact and diverging recovery De Zwarte Dood en terugkerende pestgolven tijdens de late middeleeuwen in het Graafschap Henegouwen Differentiële impact en uiteenlopend herstel (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 23 oktober 2020 des middags te 4.15 uur door Joris Roosen geboren op 8 oktober 1987 te Genk, België BinnenwerkJorisVersie2.indd 3 21/09/2020 15:45:13 Promotor: Prof. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Contents 3 7 13 14 17 21 31 34 Dear Map Friends

BIMCC Newsletter N°19, May 2004 Contents Dear Map Friends, Pictures at an Ever since the creation of the BIMCC in 1998, President Wulf Exhibition (I—III) 3 Bodenstein has tried to obtain my help in running the Circle and, in particular, in editing the Newsletter. But I knew I could not possibly Looks at Books meet his demand for quality work, while being professionally active. (I - IV) 7 Now that I have retired from Eurocontrol, I no longer have that excuse, and I am taking over from Brendan Sinnott who has been the Royal 13 Newsletter Editor for over two years and who is more and more busy Geographical at the European Commission. Society Henry Morton When opening this issue, you will rapidly see a new feature: right in 14 the middle, you will find, not the playmap of the month, but the Stanley ”BIMCC map of the season”. We hope you will like the idea and present your favourite map in the centrefold of future Newsletters. BIMCC‘s Map 17 of the Season What else will change in the Newsletter? This will depend on you ! After 18 issues of the BIMCC Newsletter, we would like to have your Mapping of the 21 views: what features do you like or dislike? What else would you like Antarctic to read? Do you have contributions to offer? Please provide your feedback by returning the enclosed questionnaire. International Should you feel ready to get further involved in supporting the News & Events 31 organisation and the activities of the Circle, you should then volunteer to become an “Active Member”, and come to the Extraordinary Auction General Meeting; this meeting, on 29 October 2004 after the BIMCC Calendar 34 excursion (see details inside) will approve the modification of the BIMCC statutes (as required by Belgian law) and agree the Enclosure — nomination of Active Members to support the Executive Committee. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153