Shetlanders Who Signed up and Would Never Make the Trip Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

We Remember Those Members of the Lloyd's Community Who Lost Their

Surname First names Rank We remember those members of the Lloyd’s community who lost their lives in the First World War 1 We remember those who lost their lives in the First World War SurnameIntroduction Today, as we do each year, Lloyd’s is holding a But this book is the story of the Lloyd’s men who fought. Firstby John names Nelson, Remembrance Ceremony in the Underwriting Room, Many joined the County of London Regiment, either the ChairmanRank of Lloyd’s with many thousands of people attending. 5th Battalion (known as the London Rifle Brigade) or the 14th Battalion (known as the London Scottish). By June This book, brilliantly researched by John Hamblin is 1916, when compulsory military service was introduced, another act of remembrance. It is the story of the Lloyd’s 2485 men from Lloyd’s had undertaken military service. men who did not return from the First World War. Tragically, many did not return. This book honours those 214 men. Nine men from Lloyd’s fell in the first day of Like every organisation in Britain, Lloyd’s was deeply affected the battle of the Somme. The list of those who were by World War One. The market’s strong connections with killed contains members of the famous family firms that the Territorial Army led to hundreds of underwriters, dominated Lloyd’s at the outbreak of war – Willis, Poland, brokers, members and staff being mobilised within weeks Tyser, Walsham. of war being declared on 4 August 1914. Many of those who could not take part in actual combat also relinquished their This book is a labour of love by John Hamblin who is well business duties in order to serve the country in other ways. -

Valortours 2016Flyer.Pdf

2-10 May 2016 $3,395 per person Space limited Twin-Share, Land Only Our Concept: Friday, 6 May 2016 We go where history was written; we Historic & Symbolic Verdun: Walking walk in the path of those who served; tour of the city's many historic sites and a visit to Vauban's Citadel; battlefield we endeavor to understand the memorials, including: Bayonet Trench, challenges they faced; we will never the famous Ossuary, and much more. forget their sacrifices. Hotel: Verdun Monday, 2 May 2016 Saturday, 7 May 2016 Arrival Day in Paris: In the evening the group assembles for our welcome dinner. The Left Bank: Destroyed villages of Haucourt & Cumières, Mort Homme, Côte Hotel: Golden Tulip at CDG Airport 304, and the Butte de Vauquois. As time allows, key sites associated with the U.S. Tuesday, 3 May 2016 Meuse-Argonne Offensive of 1918. 1914 Shapes the Verdun Battlefield: Hotel: Verdun Champagne campaigns of 1914 & 1915; earlier German attempts to capture Ver- Sunday, 8 May 2016 dun; the Voie Sacrée. The Hot Zone, High Water Mark & Hotel: Verdun End Game: Thiaumont defenses; Quatre Chiminees, Froideterre Ouvrage, Fleury Wednesday, 4 May 2016 Ravine, Fort Souville, the Fallen Lion, the recapture of Douaumont and Vaux. Opening Attack: 21 February 1916: German rear area; attack at Bois des Hotel: Verdun Caures; Verdun Memorial; destroyed Monday, 9 May 2016 village of Fleury; Meuse River positions. American Sites Near Château-Thierry Hotel: Verdun & Musée de la Grande Guerre: The Thursday, 5 May 2016 "Rock of the Marne" site; Rainbow Divi- sion Monument; Château-Thierry; and Focusing on the Forts: The two defen- Belleau Wood; the spectacular Musée de sive ridge lines; Fort Douaumont and its la Grande Guerre at Meaux; departure surprising capture; Fort Vaux and its fall; dinner at our hotel. -

Bridgwater 1914-18 Adams James Stoker Petty

Bridgwater 1914-18 Adams James Stoker Petty Officer 309198 H.M.S “Valkyrie” Royal Navy. Killed by an explosion 22nd December 1917. James Adams was the 34 year old husband of Eliza Emma Duckham (formerly Adams of 4, Halesleigh Road, Bridgwater. Born at Huntworth. Bridgwater (Wembdon Road) Cemetery Church portion Location IV. 8. 3. Adams Albert James Corporal 266852 1st/6th Battalion TF Devonshire Regiment. Died 9th February 1919. Husband of Annie Adams, of Langley Marsh, Wiveliscombe, Somereset. Bridgwater (St Johns) Cemetery. Ref 2 2572. Allen Sidney Private 7312 19th (County of London) Battalion (St Pancras) The London Regiment (141st Infantry Brigade 47th (2nd London) Territorial Division). (formerly 3049 Somerset Light Infantry). Killed in action 14th November 1916. Sydney Allen was the 29 year old son of William Charles and Emily Allen, of Pathfinder Terrace, Bridgwater. Chester Farm Cemetery, Zillebeke, West Flanders, Belgium. Plot 1. Row J Grave 9. Andrews Willaim Private 1014 West Somerset Yeomanry. Died in Malta 19th November 1915. He was the son of Walter and Mary Ann Andrews, of Stringston, Holford, Bridgwater. Pieta Military Cemetery, Malta. Plot D. Row VII. Grave 3. Anglin Denis Patrick Private 3/6773 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. (11th Infantry Brigade 4th Division). Killed in action during the attack on and around the “Quadrilateral” a heavily fortified system of enemy trenches on Redan Ridge near the village of Serre 1st July 1916 the first day of the 1916 Battle of the Somme. He has no known grave, being commemorated n the Thiepval Memorial to the ‘Missing’ of the Somme. Anglin Joseph A/Sergeant 9566 Mentioned in Despatches 1st Battalion Somerset Light Infantry. -

Learning Lessons? Fifth Army Tank Operations, 1916-1917 – Jake Gasson

Learning Lessons? Fifth Army Tank Operations, 1916-1917 – Jake Gasson Introduction On 15 September 1916, a new weapon made its battlefield debut at Flers-Courcelette on the Somme – the tank. Its debut, primarily under the Fourth Army, has overshadowed later deployments of the tank on the Somme, particularly those under General Sir Hubert de la Poer Gough’s Reserve Army, or Fifth Army as it came to be known after 30 October 1916. Gough’s operations against Thiepval and beside the Ancre made small scale usage of tanks as auxiliaries to the infantry, but have largely been ignored in historiography.1 Similarly, Gough’s employment of tanks the following spring in April 1917 at Bullecourt has only been cursorily discussed for the Australian distrust in tanks created by the debacle.2 The value in examining these further is twofold. Firstly, the examination of operations on the Somme through the case studies of Thiepval and Beaumont-Hamel presents a more positive appraisal of the tank’s impact than analysis confined to Flers-Courcelette, such as J.F.C. Fuller’s suggestion that their impact was more as the ‘birthday of a new epoch’ on 15 September than concrete success.3 Secondly, Gough’s tank operations shed a new light onto the notion of the ‘learning curve’, the idea that the British Army became a more effective ‘instrument of war’ through its experience on the Somme.4 This goes beyond the well-trodden infantry and artillery tactics, and the study of campaigns in isolation. Gough’s operations from Thiepval to Bullecourt highlight the inter-relationship between theory and practice, the distinctive nature 1 David J. -

Rushmoor Men Who Died During the Battle of the Somme

Rushmoor men who died during the Battle of the Somme Compiled by Paul H Vickers, Friends of the Aldershot Military Museum, January 2016 Introduction To be included in this list a man must be included in the Rushmoor Roll of Honour: citizens of Aldershot, Farnborough and Cove who fell in the First World War as a resident of Rushmoor at the time of the First World War. The criteria for determining residency and the sources used for each man are detailed in the Rushmoor Roll of Honour. From the Rushmoor Roll of Honour men were identified who had died during the dates of the battle of the Somme, 1 July to 18 November 1916. Men who died up to 30 November were also considered to allow for those who may have died later of wounds received during the battle. To determine if they died at the Somme, consideration was then given to their unit and the known locations and actions of that unit, whether the man was buried in one of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) Somme cemeteries or listed on a memorial to the missing of the Somme, mainly the Thiepval Memorial, or who are noted in the Roll of Honour details as having died at the Somme or as a result of wounds sustained at the Somme. The entries in this list are arranged by regiment and battalion (or battery for the Royal Artillery). For each man the entry from the Rushmoor Roll of Honour is given, and for each regiment or battalion there is a summary of its movements up to the start of the Battle of the Somme and its participation in the battle up to the time the men listed were killed. -

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson

Copyright © 2016 by Bonnie Rose Hudson Select graphics used by permission of Teachers Resource Force. All Rights Reserved. This book may not be reproduced or transmitted by any means, including graphic, electronic, or mechanical, without the express written consent of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews and those uses expressly described in the following Terms of Use. You are welcome to link back to the author’s website, http://writebonnierose.com, but may not link directly to the PDF file. You may not alter this work, sell or distribute it in any way, host this file on your own website, or upload it to a shared website. Terms of Use: For use by a family, this unit can be printed and copied as many times as needed. Classroom teachers may reproduce one copy for each student in his or her class. Members of co-ops or workshops may reproduce one copy for up to fifteen children. This material cannot be resold or used in any way for commercial purposes. Please contact the publisher with any questions. ©Bonnie Rose Hudson WriteBonnieRose.com 2 World War I Notebooking Unit The World War I Notebooking Unit is a way to help your children explore World War I in a way that is easy to personalize for your family and interests. In the front portion of this unit you will find: How to use this unit List of 168 World War I battles and engagements in no specific order Maps for areas where one or more major engagements occurred Notebooking page templates for your children to use In the second portion of the unit, you will find a list of the battles by year to help you customize the unit to fit your family’s needs. -

1 MEMORY of the WORLD REGISTER the Battle of the Somme

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER The Battle of the Somme REF N° 2004-16 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY The 1916 film The Battle of the Somme is uniquely significant both as the compelling documentary record of one of the key battles of the First World War (and indeed one which has come to typify many aspects of this landmark in 20th Century history) and as the first feature-length documentary film record of combat produced anywhere in the world. In the latter role, the film played a major part in establishing the methodology of documentary and propaganda film, and initiated debate on a number of issues relating to the ethical treatment of “factual” film which continue to be relevant to this day. Seen by many millions of British civilians within the first month of distribution, The Battle of the Somme was recognized at the time as a phenomenon that allowed the civilian home-front audience to share the experiences of the front-line soldier, thus helping both to create and to reflect the concept of Total War. Seen later by mass audiences in allied and neutral countries, including Russia and the United States, it coloured the way in which the war and British participation in it were perceived around the world at the time and subsequently, and it is the source a number of iconic images of combat on the Western Front in the First World War which remain in almost daily use ninety years later, of which two examples are reproduced below. Finally, it has importance as one of the foundation stones of the film collection of the Imperial War Museum, an institution that may claim to be among the oldest film archives in the world. -

Men of Ashdown Forest Who Fell in the First World War and Who Are Commemorated At

Men of Ashdown Forest who fell in the First World War and who are commemorated at Forest Row, Hartfield and Coleman’s Hatch Volume One 1914 - 1916 1 Copyright © Ashdown Forest Research Group Published by: The Ashdown Forest Research Group The Ashdown Forest Centre Wych Cross Forest Row East Sussex RH18 5JP Website: http://www.ashdownforest.org/enjoy/history/AshdownResearchGroup.php Email: [email protected] First published: 4 August 2014 This revised edition: 27 November 2017 © The Ashdown Forest Research Group 2 Copyright © Ashdown Forest Research Group CONTENTS Introduction 4 Index, by surname 5 Index, by date of death 7 The Studies 9 Sources and acknowledgements 108 3 Copyright © Ashdown Forest Research Group INTRODUCTION The Ashdown Forest Research Group is carrying out a project to produce case studies on all the men who died while on military service during the 1914-18 war and who are commemorated by the war memorials at Forest Row and Hartfield and in memorial books at the churches of Holy Trinity, Forest Row, Holy Trinity, Coleman’s Hatch, and St. Mary the Virgin, Hartfield.1 We have confined ourselves to these locations, which are all situated on the northern edge of Ashdown Forest, for practical reasons. Consequently, men commemorated at other locations around Ashdown Forest are not covered by this project. Our aim is to produce case studies in chronological order, and we expect to produce 116 in total. This first volume deals with the 46 men who died between the declaration of war on 4 August 1914 and 31 December 1916. We hope you will find these case studies interesting and thought-provoking. -

PDF (All Devices)

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents To my daughter Betty, the gift of God ........................................................................... 1 The heroic dead of Ireland – Marshal Foch’s tribute .................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 Casualties in Irish regiments on the first day of the Battle of the Somme .................. 10 How The Irish Times reported the Somme .................................................................. 13 An Irishman’s Diary ...................................................................................................... 17 The Irish Times editorial ............................................................................................... 20 Death of daughter of poet Thomas Kettle ................................................................... 22 How the First World War began .................................................................................. 24 Preparing for the ‘Big Push’ ........................................................................................ -

The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front, 1914-18

The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front, 1914-18 Andrew Simpson University College, London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Abstract British corps command having been neglected in the literature, this thesis sets out to assess what British corps did, and how they did it, on the Western Front during the Great War. It attempts to avoid anecdotal sources as much as possible, drawing its evidence instead as much as possible from contemporary official documents. It is a central argument here that Field Service Regulations, Part 1 (1909), was found by commanders in the BEF to be applicable throughout the war, because it was designed to be as flexible as possible, its broad principles being supplemented by training and manuals. Corps began the war in a minor role, as an extra level of command to help the C-in-C control the divisions of the BEF. With the growth in numbers and importance of artilleiy in 1915, divisions could not cope with the quantity of artilleiy allotted theni, and by early 1916, the corps BGRA became the corps artilleiy commander (GOCRA). In addition to its crucial role in artillery control, corps was important as the highest level of operational command, discussing attack plans with Armies and divisions and being responsible for putting Army schemes into practice. Though corps tended to be prescnptive towards divisions in 1916, and Armies towards corps, a more hands-off style of command was generally practised in 1917, within the framework of FSR and the pamphlet SS13S (and others - to be used with FSR). -

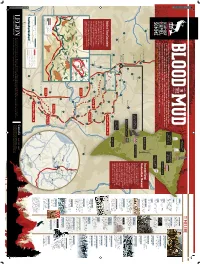

Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, Onwas Them, Trained a Few and Most Were Minutes Within Killed of the Assault

2015-12-18 2:03 PM Hunter’s CWGC TIMELINE Cemetery 1500s June 1916 English fishermen establish The regiment trains seasonal camps in Newfoundland in the rain and mud, waiting for the start of the Battle of the Somme 1610 The Newfoundland Company June 28, 1916 Hawthorn 51st (Highland) starts a proprietary colony at Cuper’s Cove near St. John’s The regiment is ordered A century ago, the Newfoundland Regiment suffered staggering losses at Beaumont-Hamel in France Ridge No. 2 Division under a mercantile charter to move to a forward CWGC Cemetery Monument granted by Queen Elizabeth I trench position, but later at the start of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. At the moment of their attack, the Newfoundlanders that day the order is postponed July 23-Aug. 7, 1916 were silhouetted on the horizon and the Germans could see them coming. Every German gun in the area 1795 Battle of Pozières Ridge was trained on them, and most were killed within a few minutes of the assault. German front line Newfoundland’s first military regiment is founded 9:15 p.m., June 30 September 1916 For more on the Newfoundland Regiment, Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, to 2 a.m., July 1, 1916 Canadian troops, moved from go to www.legionmagazine.com/BloodInTheMud. 1854 positions near Ypres, begin Newfoundland becomes a crown The regiment marches 12 kilo- arriving at the Somme battlefield Y Ravine CWGC colony of the British Empire metres to its designated trench, Cemetery dubbed St. John’s Road Sept.