Learning Lessons? Fifth Army Tank Operations, 1916-1917 – Jake Gasson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Virtual Visit - 63 to the Australian Army Museum of Western Australia

YOUR VIRTUAL VISIT - 63 TO THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY MUSEUM OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Throughout 2021, the Virtual Visit series will be continuing to present interesting features from the collection and their background stories. The Australian Army Museum of Western Australia is now open four days per week, Wednesday through Friday plus Sunday. Current COVID19 protocols including contact tracing will apply. National Memories of the Somme Beaumont Hamel, Delville Wood, Helen’s Tower, Thiepval An earlier Virtual Visit (VV61) focussed on the Australian remembrance of the Somme battles of July – November 1916. Other countries within the British Empire suffered similar trauma as national casualties mounted. They too chose to commemorate their sacrifice through evocative national memorials on the Somme battlefield. Newfoundland Regiment - Beaumont Hamel During the First World War, Newfoundland was a largely rural Dominion of the British Empire with a population of 240,000 people, and not yet part of Canada. In August 1914, Newfoundland recruited a battalion for service with the British Army. In a situation reminiscent of the khaki shortage facing the first WA Contingent to the Boer War, recruits in the Regiment were nicknamed the "Blue Puttees" due to the unusual colour of the puttees, chosen to give the Newfoundland Regiment a unique look and due to the unavailability of woollen khakis on the island. On 20 September 1915, the Regiment landed at Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli peninsula. At that stage of the campaign, the Newfoundland Regiment faced snipers, artillery fire and severe cold, as well as the trench warfare hazards of cholera, dysentery, typhus, gangrene and trench foot. -

Volume 7, Issue 2, July 2021 Introduction: New Researchers and the Bright Future of Military History

www.bjmh.org.uk British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 2, July 2021 Cover picture: Royal Navy destroyers visiting Derry, Northern Ireland, 11 June 1933. Photo © Imperial War Museum, HU 111339 www.bjmh.org.uk BRITISH JOURNAL FOR MILITARY HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD The Editorial Team gratefully acknowledges the support of the British Journal for Military History’s Editorial Advisory Board the membership of which is as follows: Chair: Prof Alexander Watson (Goldsmiths, University of London, UK) Dr Laura Aguiar (Public Record Office of Northern Ireland / Nerve Centre, UK) Dr Andrew Ayton (Keele University, UK) Prof Tarak Barkawi (London School of Economics, UK) Prof Ian Beckett (University of Kent, UK) Dr Huw Bennett (University of Cardiff, UK) Prof Martyn Bennett (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Dr Matthew Bennett (University of Winchester, UK) Prof Brian Bond (King’s College London, UK) Dr Timothy Bowman (University of Kent, UK; Member BCMH, UK) Ian Brewer (Treasurer, BCMH, UK) Dr Ambrogio Caiani (University of Kent, UK) Prof Antoine Capet (University of Rouen, France) Dr Erica Charters (University of Oxford, UK) Sqn Ldr (Ret) Rana TS Chhina (United Service Institution of India, India) Dr Gemma Clark (University of Exeter, UK) Dr Marie Coleman (Queens University Belfast, UK) Prof Mark Connelly (University of Kent, UK) Seb Cox (Air Historical Branch, UK) Dr Selena Daly (Royal Holloway, University of London, UK) Dr Susan Edgington (Queen Mary University of London, UK) Prof Catharine Edwards (Birkbeck, University of London, -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

General Sir William Birdwood and the AIF,L914-1918

A study in the limitations of command: General Sir William Birdwood and the A.I.F.,l914-1918 Prepared and submitted by JOHN DERMOT MILLAR for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales 31 January 1993 I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of advanced learning, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. John Dermot Millar 31 January 1993 ABSTRACT Military command is the single most important factor in the conduct of warfare. To understand war and military success and failure, historians need to explore command structures and the relationships between commanders. In World War I, a new level of higher command had emerged: the corps commander. Between 1914 and 1918, the role of corps commanders and the demands placed upon them constantly changed as experience brought illumination and insight. Yet the men who occupied these positions were sometimes unable to cope with the changing circumstances and the many significant limitations which were imposed upon them. Of the World War I corps commanders, William Bird wood was one of the longest serving. From the time of his appointment in December 1914 until May 1918, Bird wood acquired an experience of corps command which was perhaps more diverse than his contemporaries during this time. -

Bullecourt: Arras Free

FREE BULLECOURT: ARRAS PDF Graham Keech | 160 pages | 01 May 1999 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9780850526523 | English | Barnsley, United Kingdom Visit the Bullecourt museum- Arras Pays d'Artois Tourisme Home Remembrance At Bullecourt: Arrasimmerse yourself in Bullecourt: Arras private world of the Australian soldiers. Here, History is made tangible through the personal effects on display, turning into strong emotion when presented with all those Australian and British soldiers who perished on Artois soil. A heavy machine gun, a tank turret, ripped open gas cylinders. These are what Jean Letaille happened upon Bullecourt: Arras fine day, as he Bullecourt: Arras in his fields. It is hard to imagine the scene, so Bullecourt: Arras must it have seemed. What ensued was even more so. Today, they all find a home under the roof of his own barn, now a museum. The only source of natural light is Bullecourt: Arras sunlight that filters through holes in an enormous door, which one might describe as… riddled with bullets. It is the golden voice of Bullecourt: Arras Letaille himself that accompanies the visitor in this emotionally charged place. An accumulation of shells, horse shoes, barbed wire, rifles and everything making up the kit of a soldier of the First World War. The staging is brutal. All around, display cases filled with personal effects, all neatly arranged like toy soldiers, stand in stark contrast to the disarray Bullecourt: Arras confusion of the central pit. But perhaps this re-enacts the two battles of Bullecourt which, in the spring ofleft 17, dead from among the Australian and British ranks? The Letaille museum is an enduring allegory: it explains by showing. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

The Evolution of British Tactical and Operational Tank Doctrine and Training in the First World War

The evolution of British tactical and operational tank doctrine and training in the First World War PHILIP RICHARD VENTHAM TD BA (Hons.) MA. Thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy by the University of Wolverhampton October 2016 ©Copyright P R Ventham 1 ABSTRACT Tanks were first used in action in September 1916. There had been no previous combat experience on which to base tactical and operational doctrine for the employment of this novel weapon of war. Training of crews and commanders was hampered by lack of vehicles and weapons. Time was short in which to train novice crews. Training facilities were limited. Despite mechanical limitations of the early machines and their vulnerability to adverse ground conditions, the tanks achieved moderate success in their initial actions. Advocates of the tanks, such as Fuller and Elles, worked hard to convince the sceptical of the value of the tank. Two years later, tanks had gained the support of most senior commanders. Doctrine, based on practical combat experience, had evolved both within the Tank Corps and at GHQ and higher command. Despite dramatic improvements in the design, functionality and reliability of the later marks of heavy and medium tanks, they still remained slow and vulnerable to ground conditions and enemy counter-measures. Competing demands for materiel meant there were never enough tanks to replace casualties and meet the demands of formation commanders. This thesis will argue that the somewhat patchy performance of the armoured vehicles in the final months of the war was less a product of poor doctrinal guidance and inadequate training than of an insufficiency of tanks and the difficulties of providing enough tanks in the right locations at the right time to meet the requirements of the manoeuvre battles of the ‘Hundred Days’. -

Beaumont-Hamel One Hundred Years Later in Most of Our Country, July 1St 68 Were There to Answer the Roll Call

Veterans’Veterans’ WeekWeek SSpecialpecial EditionEdition - NovemberNovember 55 toto 11, 11, 2016 2016 Beaumont-Hamel one hundred years later In most of our country, July 1st 68 were there to answer the roll call. is simply known as Canada Day. It was a blow that touched almost In Newfoundland and Labrador, every community in Newfoundland. however, it has an additional and A century later the people of the much more sombre meaning. There, province still mark it with Memorial it is also known as Memorial Day—a Day. time to remember those who have served and sacrificed in uniform. The regiment would rebuild after this tragedy and it would later earn the On this day in 1916 near the French designation “Royal Newfoundland village of Beaumont-Hamel, some Regiment” for its members’ brave 800 soldiers from the Newfoundland actions during the First World Regiment went into action on the War. Today, the now-peaceful opening day of the Battle of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Somme. The brave men advanced Memorial overlooks the old into a thick hail of enemy fire, battlefield and commemorates the instinctively tucking their chins Newfoundlanders who served in the down as if they were walking through conflict, particularly those who have a snowstorm. In less than half an no known grave. Special events were hour of fighting, the regiment would held in Canada and France to mark Affairs Canada Veterans Photo: th be torn apart. The next morning, only the 100 anniversary in July 2016. Caribou monument at the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial. Force C in The Gulf War not forgotten Against all Hong Kong Our service members played a variety of roles, from crewing odds three Canadian warships with the Coalition fleet, to flying CF-18 jet fighters in attack missions, to Photo: Department of National Department of National Photo: Defence ISC91-5253 operating a military hospital, and at Canadian Armed Forces CF-18 readying more. -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 by John Bilcliffe edited and amended in 2016 by Peter Nelson and Steve Shannon Part 4 The Casualties. Killed in Action, Died of Wounds and Died of Disease. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License You can download this work and share it with others as long as it is credited, but you can’t change it in any way or use it commercially © John Bilcliffe. Email [email protected] Part 4 Contents. 4.1: Analysis of casualties sustained by The Durham Light Infantry on the Somme in 1916. 4.2: Officers who were killed or died of wounds on the Somme 1916. 4.3: DLI Somme casualties by Battalion. Note: The drawing on the front page of British infantrymen attacking towards La Boisselle on 1 July 1916 is from Reverend James Birch's war diary. DCRO: D/DLI 7/63/2, p.149. About the Cemetery Codes used in Part 4 The author researched and wrote this book in the 1990s. It was designed to be published in print although, sadly, this was not achieved during his lifetime. Throughout the text, John Bilcliffe used a set of alpha-numeric codes to abbreviate cemetery names. In Part 4 each soldier’s name is followed by a Cemetery Code and, where known, the Grave Reference, as identified by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Here are two examples of the codes and what they represent: T2 Thiepval Memorial A5 VII.B.22 Adanac Military Cemetery, Miraumont: Section VII, Row B, Grave no. -

Tanks and Tank Warfare | International Encyclopedia of The

Version 1.0 | Last updated 17 May 2016 Tanks and Tank Warfare By Michael David Kennedy World War I introduced new technologies and doctrine in a quest to overcome the tactical stalemate of the trenches. The first tanks had great potential that would be capitalized upon during the next world war, but early models suffered from design flaws and lack of doctrine for their use on the battlefield. Table of Contents 1 Definition and Background 2 Characteristics 3 Development in Great Britain 4 Battle of the Somme (1 July-18 November 1916) 5 Battle of Cambrai (20-30 November 1917) 6 French Tanks 7 German Tanks 8 Tanks in the American Expeditionary Forces 9 Impact of Tanks on World War I Selected Bibliography Citation Definition and Background Tanks are armored vehicles designed to combine the military factors of fire, maneuver and protection. Although the concept of armored vehicles preceded the Great War, the tank was specifically developed to overcome the stalemate of trench warfare on the Western Front that followed the First Battle of Ypres (19 October-22 November 1914). The marrying of recent technological advances, such as the internal combustion engine with armor plating, enabled the tank’s development during World War I. Characteristics The first tanks introduced in 1916 were generally slow and hard to maneuver, and they performed poorly in rugged terrain. The early models were heavily influenced by commercial tractors. While impervious to barbed wire, small arms, and shrapnel, their primitive armor was still susceptible to heavy machine gun fire and direct hits from high explosive artillery rounds. -

Grimes, Ronald

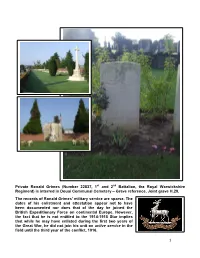

Private Ronald Grimes (Number 22837, 1st and 2nd Battalion, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment) is interred in Douai Communal Cemetery – Grave reference, Joint grave H.29. The records of Ronald Grimes’ military service are sparse. The dates of his enlistment and attestation appear not to have been documented nor does that of the day he joined the British Expeditionary Force on continental Europe. However, the fact that he is not entitled to the 1914-1915 Star implies that while he may have enlisted during the first two years of the Great War, he did not join his unit on active service in the field until the third year of the conflict, 1916. 1 Furthermore, the recorded (in places) service of Private Grimes with both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Warwicks leads one to believe that this was also the order in which he was attached to them. *However, there appears to be little further evidence of Private Grimes serving with the 2nd Battalion of the Regiment. The Forces War Records web-site has him with the 1st. Both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Royal Warwickshire had been ordered to the Continent in 1914. The 1st Battalion had fought in the Retreat from Mons and then in the Race to the Sea, the campaign which ensured the static nature of the Great War for the next few years. It had been stationed in Belgium at the time of the Second Battle of Ypres, then in northern France until 1916 when the British assumed responsibility for the area of the Somme from the French. -

A- 1969 B.R.G.M, Inventaire Des Ressources Hydrauliques

T- BUREAU DE RECHERCHES GÉOLOGIQUES ET MINIERES DEPARTEMENT DES SERVICES GEOLOGIQUES REGIONAUX INVENTAIRE DES RESSOURCES HYDRAULIQUES DES DÉRû,RTEMENTS DU NORD ET DU PAS DE CALAIS FEUILLE TOPOGRAPHIQUE AU 1/20000 DE: CAMBRAI n-36 Coupures 1-2-3 Données hydrogèologiques acquises à la date du 15 Novembre 1901 par R CAMBIER P. DOUVRIN E.LEROUX J.RICOUR G. WATERLOT ^ Bji" G. r>lN^ ñiBLÍÓTHEQÜTj A- 1969 B.R.G.M, Inventaire des ressources hydrauliques BUREAU DE RECHERCHES des départements du Nord et du Pas-de-Calals GEOLOGIQUES & MINIERES 20, quai des Fontainettes DOUAI (Nord) 74, rue de la Fédération Tél. : 88-98-05 PARIS (15°) département des services géologiques régionaux Tél. : Suf, 94,00 DONNEES HYDROGEOLOGIQUES ACQUISES A LA DATE du 15 novembre 1961 sur le territoire de la FEUILLE TOPOGRAPHIQUE AU l/20 000 DE CAMBRAI (N" 36) (coupures n 1 - 2 et 3) par P. CAMBIER - J,¥i, DEZVÍARTE - P. DOUVRIN G. DASC0NVILL3 - E. LEROUX - J.RICOUR - G. WATERLOT Paris, le 14 février 1962 - 2 - SOMMAIRE Pages INTRODUCTION 5 1. DONNEES GENERALES 6 11 - Régions naturelles 6 12 - Hydrographie 6 13 - Végétation naturelle et cultures ............ 9 14 - Habitat et industrie 9 15 - Météorologie 9 2. GEOLOGIE 10 21 - Quaternaire 10 22 - Tertiaire 12 23 - Secondaire 12 231 - Sénonien 12 232 - Turonien supérieur 12 233 - Turonien moyen 13 234 - Turonien inférieur 13 235 - Cénomanien 13 24 - Primaire 13 25 - Tectonique 15 3. EAUX SOUTERRAINES 16 31 - Nappes d'importance secondaire 16 311 - Tertiaire 16 312 - Cénomanien 16 32 - Remarque 16 321 - Quaternaire 16 322 - Primaire 17 32 - Nappe d'importance principale - nappe de la craie 17 331 - Turonien moyen 17 332 - Turonien inférieur 17 - 3 - 333 - Turonien supérieur et Sénonien 18 3331 - Situation générale de la nappe .