CHAPTER VI11 WHEN on March 17Th the Germans Withdrew Their Front

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bullecourt: Arras Free

FREE BULLECOURT: ARRAS PDF Graham Keech | 160 pages | 01 May 1999 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9780850526523 | English | Barnsley, United Kingdom Visit the Bullecourt museum- Arras Pays d'Artois Tourisme Home Remembrance At Bullecourt: Arrasimmerse yourself in Bullecourt: Arras private world of the Australian soldiers. Here, History is made tangible through the personal effects on display, turning into strong emotion when presented with all those Australian and British soldiers who perished on Artois soil. A heavy machine gun, a tank turret, ripped open gas cylinders. These are what Jean Letaille happened upon Bullecourt: Arras fine day, as he Bullecourt: Arras in his fields. It is hard to imagine the scene, so Bullecourt: Arras must it have seemed. What ensued was even more so. Today, they all find a home under the roof of his own barn, now a museum. The only source of natural light is Bullecourt: Arras sunlight that filters through holes in an enormous door, which one might describe as… riddled with bullets. It is the golden voice of Bullecourt: Arras Letaille himself that accompanies the visitor in this emotionally charged place. An accumulation of shells, horse shoes, barbed wire, rifles and everything making up the kit of a soldier of the First World War. The staging is brutal. All around, display cases filled with personal effects, all neatly arranged like toy soldiers, stand in stark contrast to the disarray Bullecourt: Arras confusion of the central pit. But perhaps this re-enacts the two battles of Bullecourt which, in the spring ofleft 17, dead from among the Australian and British ranks? The Letaille museum is an enduring allegory: it explains by showing. -

Mouvement Départemental Du Pas-De-Calais Enseignants Du 1Er Degré Public 2021

MOUVEMENT DÉPARTEMENTAL DU PAS-DE-CALAIS ENSEIGNANTS DU 1ER DEGRÉ PUBLIC 2021 LISTE N°2 REGROUPEMENTS GÉOGRAPHIQUES ET COMMUNES RATTACHÉES ACHICOURT et ARRAS Sud ACHICOURT FICHEUX ADINFER HENDECOURT LES RANSART AGNY HENINEL BEAUMETZ LES LOGES HENIN SUR COJEUL BEAURAINS MERCATEL BERNEVILLE NEUVILLE VITASSE BLAIRVILLE RANSART BOIRY BECQUERELLE RIVIÈRE BOIRY ST MARTIN SAINT MARTIN SUR COJEUL BOIRY STE RICTRUDE TILLOY LES MOFFLAINES BOISLEUX AU MONT WAILLY BOYELLES WANCOURT AIRE SUR LA LYS AIRE SUR LA LYS ROQUETOIRE BLESSY WARDRECQUES RACQUINGHEM WITTES ANNEZIN ANNEZIN VENDIN LES BÉTHUNE HINGES ARDRES ARDRES NORDAUSQUES BALINGHEM RODELINGHEM BRÈMES TOURNEHEM SUR LA HEM LANDRETHUN LES ARDRES ZOUAFQUES LOUCHES ARQUES et LONGUENESSE ARQUES LONGUENESSE CAMPAGNE LES WARDRECQUES ARRAS Ville ARRAS ARRAS Nord ACQ MONT ST ÉLOI ANZIN ST AUBIN SAINTE CATHERINE DAINVILLE THELUS DUISANS VIMY MAROEUIL AUBIGNY AGNIERES FREVILLERS AMBRINES FREVIN CAPELLE AUBIGNY EN ARTOIS HERMAVILLE BAJUS IZEL LES HAMEAUX BERLES MONCHEL MAGNICOURT EN COMTE BETHONSART PENIN CAMBLIGNEUL SAVY BERLETTE CAMBLAIN L’ABBÉ TILLOY LES HERMAVILLE CHELERS TINCQUES LA COMTE VILLERS BRULIN ESTREE CAUCHY VILLERS CHATEL AUCHEL AMES FERFAY AMETTES LOZINGHEM AUCHEL LIÈRES CAUCHY A LA TOUR AUCHY LES HESDIN AUCHY LES HESDIN LE PARCQ BLANGY SUR TERNOISE ROLLANCOURT GRIGNY WAMIN AUCHY LES MINES AUCHY LES MINES GIVENCHY LES LA BASSÉE CAMBRIN HAISNES CUINCHY VIOLAINES AUDRUICQ AUDRUICQ RECQUES SUR HEM MUNCQ NIEURLET RUMINGHEM NORTKERQUE SAINTE MARIE KERQUE POLINCOVE ZUTKERQUE AUXI LE CHÂTEAU AUXI -

A- 1969 B.R.G.M, Inventaire Des Ressources Hydrauliques

T- BUREAU DE RECHERCHES GÉOLOGIQUES ET MINIERES DEPARTEMENT DES SERVICES GEOLOGIQUES REGIONAUX INVENTAIRE DES RESSOURCES HYDRAULIQUES DES DÉRû,RTEMENTS DU NORD ET DU PAS DE CALAIS FEUILLE TOPOGRAPHIQUE AU 1/20000 DE: CAMBRAI n-36 Coupures 1-2-3 Données hydrogèologiques acquises à la date du 15 Novembre 1901 par R CAMBIER P. DOUVRIN E.LEROUX J.RICOUR G. WATERLOT ^ Bji" G. r>lN^ ñiBLÍÓTHEQÜTj A- 1969 B.R.G.M, Inventaire des ressources hydrauliques BUREAU DE RECHERCHES des départements du Nord et du Pas-de-Calals GEOLOGIQUES & MINIERES 20, quai des Fontainettes DOUAI (Nord) 74, rue de la Fédération Tél. : 88-98-05 PARIS (15°) département des services géologiques régionaux Tél. : Suf, 94,00 DONNEES HYDROGEOLOGIQUES ACQUISES A LA DATE du 15 novembre 1961 sur le territoire de la FEUILLE TOPOGRAPHIQUE AU l/20 000 DE CAMBRAI (N" 36) (coupures n 1 - 2 et 3) par P. CAMBIER - J,¥i, DEZVÍARTE - P. DOUVRIN G. DASC0NVILL3 - E. LEROUX - J.RICOUR - G. WATERLOT Paris, le 14 février 1962 - 2 - SOMMAIRE Pages INTRODUCTION 5 1. DONNEES GENERALES 6 11 - Régions naturelles 6 12 - Hydrographie 6 13 - Végétation naturelle et cultures ............ 9 14 - Habitat et industrie 9 15 - Météorologie 9 2. GEOLOGIE 10 21 - Quaternaire 10 22 - Tertiaire 12 23 - Secondaire 12 231 - Sénonien 12 232 - Turonien supérieur 12 233 - Turonien moyen 13 234 - Turonien inférieur 13 235 - Cénomanien 13 24 - Primaire 13 25 - Tectonique 15 3. EAUX SOUTERRAINES 16 31 - Nappes d'importance secondaire 16 311 - Tertiaire 16 312 - Cénomanien 16 32 - Remarque 16 321 - Quaternaire 16 322 - Primaire 17 32 - Nappe d'importance principale - nappe de la craie 17 331 - Turonien moyen 17 332 - Turonien inférieur 17 - 3 - 333 - Turonien supérieur et Sénonien 18 3331 - Situation générale de la nappe . -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

Extract of the 1St Essex Regiment Diary Source

Extract of the 1st Essex regiment diary Source: Chelmsford War Memorial “Orders to attack came at short notice to the 112th Brigade. At 4 a.m. on the 23rd the 3rd Division captured Gomiecourt, which had an important influence on the operations in this quarter. Its commander agreed to co-operate with the 37th Division in a further forward movement, the immediate objective of the latter being the village of Achiet-le-Grand, which the enemy held in some strength. On the right the 5th Division were advancing on Irles. Not only was the ground rendered difficult by the cutting of the Arras-Amiens railway - which was in places 35 feet deep - and the track running from the last-named village to Bapaume, but the enemy had planted machine guns along it on the average of one to every twenty yards. There were also numerous banks and trenches which served as cover. A large brickworks in front of the railway and opposite Achiet-le-Grand was strongly held, as was also a spur to the south, which was later to prove very troublesome to the Essex. The 112th Infantry Brigade operated in a south-easterly direction from Achiet-le-Petit, having experienced some difficulty in forming up north of the village owing to the disorganised state of some units of another division which had recently attacked, and to the lack of reconnaissance. Touch with the 5th Division had not been established at zero hour. 111th Brigade were on the left with Achiet-le-Grand as the objective. To 13th Royal Fusiliers was allotted the capture of the railway cutting and the road beyond south of Achiet-le-Grand, the 1st Herts. -

We Remember Those Members of the Lloyd's Community Who Lost Their

Surname First names Rank We remember those members of the Lloyd’s community who lost their lives in the First World War 1 We remember those who lost their lives in the First World War SurnameIntroduction Today, as we do each year, Lloyd’s is holding a But this book is the story of the Lloyd’s men who fought. Firstby John names Nelson, Remembrance Ceremony in the Underwriting Room, Many joined the County of London Regiment, either the ChairmanRank of Lloyd’s with many thousands of people attending. 5th Battalion (known as the London Rifle Brigade) or the 14th Battalion (known as the London Scottish). By June This book, brilliantly researched by John Hamblin is 1916, when compulsory military service was introduced, another act of remembrance. It is the story of the Lloyd’s 2485 men from Lloyd’s had undertaken military service. men who did not return from the First World War. Tragically, many did not return. This book honours those 214 men. Nine men from Lloyd’s fell in the first day of Like every organisation in Britain, Lloyd’s was deeply affected the battle of the Somme. The list of those who were by World War One. The market’s strong connections with killed contains members of the famous family firms that the Territorial Army led to hundreds of underwriters, dominated Lloyd’s at the outbreak of war – Willis, Poland, brokers, members and staff being mobilised within weeks Tyser, Walsham. of war being declared on 4 August 1914. Many of those who could not take part in actual combat also relinquished their This book is a labour of love by John Hamblin who is well business duties in order to serve the country in other ways. -

+Mcvitty, Trevor Maynard Watt

remembrance ni Anniversary of victory in Battle of Monte Cassino Page 1 This day in 1944, Polish, British and other Allied forces captured Monte Cassino, Italy, after 123 days of heavy fighting. 55,000 Allied troops became casualties in 123 days of fighting. The Battle of Monte Cassino, arguably one of the most intense and demanding of the war. It is worth recalling the circumstances that led to this protracted engagement on the Italian peninsula. With the Axis surrendering in North Africa, the Allies had just passed their first real test. The road to Rome appeared open. +++++ 18th May 1944 Letter from Lt. Room to Olive Franklyn-Vaile "Yesterday morning, about quarter to eight, Lawrie died. I was about five yards from him when the shell exploded so was with him immediately. I am certain he was not conscious after he had been hit and so suffered no pain.” Major Lawrie Franklyn-Vaile was a company commander of RIF +++++ Halfway up the boot of Italy, however, Allied troops encountered a series of coast-to-coast defensive fortifications known as the Winter Line, with the magnificent Roman Catholic abbey of Monte Cassino at its apex. Built in Page 2 John Horsfall, CO 2 London Irish Rifles, north of Cassino, 18 May 1944; "We remained in the vicinity of Piumarola for the rest of that day, the 18th &, during the morning, I sent out a further patrol westwards. But all that F Coy could find was a rather scruffy jager, who had clearly got lost. Not a shot was fired at us all morning and in this strange lull, hardly a gun opened up in the whole of the sector..." the sixth century, its hilltop vantage point dominated access to the Liri and Rapido valleys – and the road to Rome. -

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs

PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS RECUEIL n°33 du 17 MAI 2019 Le Recueil des Actes Administratifs sous sa forme intégrale est consultable en Préfecture, dans les Sous-Préfectures, ainsi que sur le site Internet de la Préfecture (www.pas-de-calais.gouv.fr) rue Ferdinand BUISSON - 62020 ARRAS CEDEX 9 tél. 03.21.21.20.00 fax 03.21.55.30.30 CABINET DU PRÉFET...........................................................................................................4 Direction des Sécurités - Bureau de la Réglementation de Sécurité...................................................................................4 - Arrêté en date du 15 mai 2019 portant nomination aux présidences des commissions d’arrondissements de sécurité incendie..................................................................................................................................................................................4 Direction des Sécurités – Service Interministériel de Défense et de Protection Civiles....................................................5 - Arrêté en date du 13 mai 2019 portant désignation du référent départemental « Sûreté Portuaire ».................................5 DIRECTION DÉPARTEMENTALE D’INCENDIE ET DE SECOURS DU PAS-DE-CALAIS...7 - Arrêté n°19-1533 en date du 6 mai 2019 portant tableaux d’avancements au grade de Médecin et pharmacien hors classe de sapeurs-pompiers professionnels du Pas-de-Calais au titre de l'année 2019..........................................................7 - Arrêté n°19-1530 en date -

Vacances De PRINTEMPS 2018

FICHE D’INSCRIPTION Nom : ………………………………. Prénom : ……………………. Age : ………… ACCUEIL DE LOISIRS DE : ……………………………………. Vacances de PRINTEMPS 2018 En cas d’annulation de dernière minute, merci de prévenir au plus tard le mercredi 18 avril avant 18h00 la semaine précédente. Dans le cas contraire, la semaine sera due. Vac. De printemps Semaine du 23/04 au 27/04/2018 Bus matin Bus soir Lieu de ramassage Vac. De printemps Semaine du 30/04 au 04/05/2018 Bus matin Bus soir Lieu de ramassage TARIFICATION FORFAITAIRE (inclus : garderie, restauration, activités, transports) Ressortissants CAF Coefficient CAF < 750 Coefficient CAF > 750 Semaine du 23/04 au 27/04 30,00 € 35,00 € Semaine du 30/04 au 04/05 24,00 € 28,00 € Extérieur par enfant et par semaine Supplément de 10,00 € Pour la tarification, merci de vous rapprocher du Ressortissants MSA directeur concerné ou à la CCSA siège de Bapaume afin de connaître le coût réel de l'inscription Souhaiteriez-vous une facture acquittée : oui non MODALITE DE PAIEMENT Cadre réservé à la CCSA Mode de règlement : Chèque Espèce € Autre Facture n° Reçu envoyé le : / / 2018 Clôture des inscriptions le mercredi 18 avril CIRCUITS DE RAMASSAGE Un bus viendra chercher chaque matin les enfants inscrits et les ramènera le soir. En dehors des circuits prévus par la collectivité, le transport est à la charge des parents. Important ! Les enfants qui fréquentent le service de ramassage le matin restent sous la responsabilité de leurs parents ou d’un adulte désigné par la famille jusqu’à la montée dans le bus. Il en est de même le soir à la descente. -

Learning Lessons? Fifth Army Tank Operations, 1916-1917 – Jake Gasson

Learning Lessons? Fifth Army Tank Operations, 1916-1917 – Jake Gasson Introduction On 15 September 1916, a new weapon made its battlefield debut at Flers-Courcelette on the Somme – the tank. Its debut, primarily under the Fourth Army, has overshadowed later deployments of the tank on the Somme, particularly those under General Sir Hubert de la Poer Gough’s Reserve Army, or Fifth Army as it came to be known after 30 October 1916. Gough’s operations against Thiepval and beside the Ancre made small scale usage of tanks as auxiliaries to the infantry, but have largely been ignored in historiography.1 Similarly, Gough’s employment of tanks the following spring in April 1917 at Bullecourt has only been cursorily discussed for the Australian distrust in tanks created by the debacle.2 The value in examining these further is twofold. Firstly, the examination of operations on the Somme through the case studies of Thiepval and Beaumont-Hamel presents a more positive appraisal of the tank’s impact than analysis confined to Flers-Courcelette, such as J.F.C. Fuller’s suggestion that their impact was more as the ‘birthday of a new epoch’ on 15 September than concrete success.3 Secondly, Gough’s tank operations shed a new light onto the notion of the ‘learning curve’, the idea that the British Army became a more effective ‘instrument of war’ through its experience on the Somme.4 This goes beyond the well-trodden infantry and artillery tactics, and the study of campaigns in isolation. Gough’s operations from Thiepval to Bullecourt highlight the inter-relationship between theory and practice, the distinctive nature 1 David J. -

Circuits De Ramassage

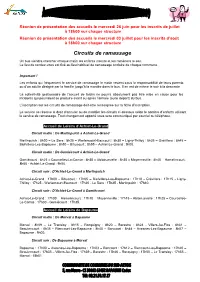

Réunion de présentation des accueils le mercredi 26 juin pour les inscrits de juillet à 18h00 sur chaque structure Réunion de présentation des accueils le mercredi 03 juillet pour les inscrits d’août à 18h00 sur chaque structure Circuits de ramassage Un bus viendra chercher chaque matin les enfants inscrits et les ramènera le soir. Le lieu de rendez-vous est fixé au lieu habituel de ramassage scolaire de chaque commune. Important ! Les enfants qui fréquentent le service de ramassage le matin restent sous la responsabilité de leurs parents ou d’un adulte désigné par la famille jusqu’à la montée dans le bus. Il en est de même le soir à la descente. La collectivité gestionnaire de l’accueil de loisirs ne pourra absolument pas être mise en cause pour les incidents qui pourraient se produire avant ou après l’arrivée (ou le départ) du bus. L’inscription sur les circuits de ramassage doit-être renseignée sur la fiche d’inscription. Le service se réserve le droit d’annuler ou de modifier les circuits ci-dessous selon le nombre d’enfants utilisant le service de ramassage. Tout changement apporté vous sera communiqué par courriel ou téléphone. Accueil de Loisirs d’Achiet-Le-Grand Circuit matin : De Martinpuich à Achiet-Le-Grand Martinpuich : 8h20 – Le Sars : 8h25 – Warlencourt-Eaucourt : 8h30 – Ligny-Thilloy : 8h35 – Grévillers : 8h45 – Biefvillers-Les-Bapaume : 8h50 – Bihucourt : 8h55 – Achiet-Le-Grand : 9h00. Circuit matin : De Gomiécourt à Achiet-Le-Grand Gomiécourt : 8h25 – Courcelles-Le-Comte : 8h30 – Ablainzevelle : 8h35 – Moyenneville : 8h45 – Hamelincourt : 8h50 - Achiet-Le-Grand : 9h00. Circuit soir : D’Achiet-Le-Grand à Martinpuich Achiet-Le-Grand : 17h00 - Bihucourt : 17h05 – Biefvillers-Les-Bapaume : 17h10 - Grévillers : 17h15 - Ligny- Thilloy : 17h25 - Warlencourt-Eaucourt : 17h30 - Le Sars : 17h35 - Martinpuich : 17h40. -

Lance-Corporal Sydney Vernon Pickering

Lance-Corporal Sydney Vernon Pickering The British Fifth Army attacks on the Somme front stopped over the winter of 1916. They were reduced to surviving the rain, snow, fog, mud fields, waterlogged trenches and shell- holes. As preparations for the spring offensive at Arras began, the 1/4th Battalion of the 12th Battalion Middlesex Regiment prepared to capture the village of Bihucourt in early March 1917. The attacks commenced in January in the Ancre Valley against exhausted German troops holding poor defensive positions left from the fighting in 1916. The Pickering family can trace their origins back to James Pickering and his wife Jane, both born, c1801, in Staffordshire. In the 1841 census James, a ‘tallow chandler’ is living with his family of five sons and a daughter in Upper Green, Newcastle under Lyme. James’ eldest son John was born on 20th November 1820 at Etruriai and baptised at St Giles Church, Newcastle under Lyme on 3rd December 1820.ii John, like his father, became a tallow chandler.iii On 30th August 1846, John married Frances Williams, daughter of Edward Williams a basket maker at Bishop Ryder’s Church, Gem Street, Gosta Green, Birmingham (now demolished to make way for building Aston University). John’s address given on the marriage certificate was 1, Nelson Street South. By 1851, John and Frances and their five children (Mary, their first child is not recorded in the 1851 census but reappears in the 1861 census) are living at 24a, Fordrough Street, Birmingham. John is now Figure 1: Bishop Ryder’s Church, a ‘master chandler, employer and Gosta Green, Birmingham manufacturer’.