New North Star

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2019 Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery Jake Spangler DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Spangler, Jake, "Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery" (2019). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June 2019 BY Jake C. Spangler Department of English College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois This project is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Jim Cowan Father, Friend, Teacher Table of Contents Dedication / i Table of Contents / ii Acknowledgements / iii Introduction / 1 I. “I Could Not Deem Myself a Slave” / 9 II. The Heroic Slave / 26 III. The “Files” of Frederick Douglass / 53 Bibliography / 76 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the support of several scholars and readers. -

Rochester's Frederick Douglass, Part

ROCHESTER HISTORY Vol. LXVII Fall, 2005 No. 4 Rochester's Frederick Douglass Part Two by Victoria Sandwick Schmitt Underground Railroad From History of New York State, edited by Alexander C. Flick. Volume 7. New York: Columbia University Press, 1935 Courtesy of the Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, NY 1 Front page from Douglass’ Monthly, Courtesy of the Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, NY ROCHESTER HISTORY, published by the Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County. Address correspondence to Local History and Genealogy Division, Rochester Public Library, 115 South Avenue, Rochester, NY 14604. Subscriptions to Rochester History are $8.00 per year by mail. Foreign subscriptions are $12.00 per year, $4.00 per copy for individual issues. Rochester History is funded in part by the Frances Kenyon Publication Fund, established in memory of her sister, Florence Taber Kenyon and her friend Thelma Jeffries. CONOLLY PRINTING-2 c CITY OF ROCHESTER 2007 2 2 Douglass Sheltered Freedom Seekers The Douglass family only lived on Alexander Street for four years before relocating in 1852 to a hillside farm south of the city on what is now South Avenue. Douglass’ farm stood on the outskirts of town, amongst sparsely settled hills not far from the Genesee River. The Douglasses did not sell their Alexander Street house. They held it as the first of several real estate investments, which were the foundation of financial security for them as for many enterprising African American families. 71 The Douglasses’ second residence consisted of a farm with a framed dwelling, orchard and barn. In 2005, a marker in front of School 12 on South Avenue locates the site, near Highland Park. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass As a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Theology Faculty Publications Theology 10-1988 And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass as a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895 Gabriel Pivarnik Providence College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_fac Part of the Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Pivarnik, Gabriel, "And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass as a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895" (1988). Theology Faculty Publications. 5. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_fac/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AND HE WAS NO SOFT-TONGUED APOLOGIST: FREDERICK DOUGLASS AS A CONSTITUTIONAL THEORIST, 1865-1895 A Paper Presented to the National Endowment for the Humanities for the Younger Scholars Grant Program 1988 by Robert George Pivarnik October, 1988 And he was no soft-tongued apologist; He spoke straightforward, fearlessly uncowed The sunlight of his truth dispelled the mist, And set in bold relief each dark-hued cloud; To sin and crime he gave their proper hue, And hurled at evil what was evil's due. Paul Lawrence Dunbar, "Frederick Douglass" Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the work of Waldo E. Martin on the psychology of Frederick Douglass. If it were not for Martin's research, this project would never have gotten underway. I would also like to thank Elizabeth Ackert and the staff of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Library who were instrumen tal in helping me obtain the necessary resources for this work. -

Julia Faisst, Phin Beiheft

PhiN Beiheft | Supplement 5/2012: 71 Julia Faisst (Siegen) Degrees of Exposure: Frederick Douglass, Daguerreotypes, and Representations of Freedom1 This essay investigates the picture-making processes in the writings of Frederick Douglass, one of the most articulate critics of photography in the second half of the nineteenth century. Through his fiction, speeches on photography, three autobiographies, and frontispieces, he fashioned himself as the most "representative" African American of his time, and effectively updated and expanded the image of the increasingly emancipated African American self. Tracing Douglass's project of self-fashioning – both of himself and his race – with the aid of images as well as words is the major aim of this essay. Through a close reading of the historical novella "The Heroic Slave," I examine how the face of a slave imprints itself on the photographic memory of a white man as it would on a silvered daguerreotype plate – transforming the latter into a committed abolitionist. The essay furthermore uncovers how the transformation of the novella's slave into a free man is described in terms of various photographic genres: first a "type," Augustus Washington (whose life story mirrors that of Douglass) changes into a subject worthy of portraiture. As he explored photographic genres in his writings, Douglass launched the genre of African American fiction. Moreover, through his pronounced interest in mixed media, he functioned as an immediate precursor to modernist authors who produced literature on the basis of photographic imagery. Overall, this essay reveals how Douglass performed his own progress within his photographically inflected writings, and turned both himself and his characters into free people. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

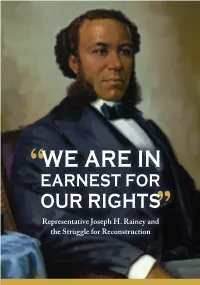

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

When Sons Remember Their Fathers

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History Winter 1997 When Sons Remember Their Fathers Bruce Dorsey Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Bruce Dorsey. (1997). "When Sons Remember Their Fathers". Kenyon Review. Volume 19, Issue 1. 162-166. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/120 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRUCE DORSEY WHEN SONS REMEMBER THEIR FATHERS Fathering the Nation: American Genealogies of Slavery and Freedom. By Russ Castronovo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. 295 pp. $32.00. Over the past half decade, historians of American culture have been attracted to two quite disparate avenues of inquiry, one involving a heightened understanding of memory and the second expanding the parameters of gender to include the meanings of masculinity. Certainly the mythic and cultural significance of the "Founding Fathers" for a generation of Americans on the eve of the Civil War offers a rich field for exploring both of these. An understanding of the "Founding Fathers" demands an analysis of the relationships between fathers and sons (both real and metaphorical) as well as the manner in which different antebellum Americans constructed -

1. Slavery, Resistance and the Slave Narrative

“I have often tried to write myself a pass” A Systemic-Functional Analysis of Discourse in Selected African American Slave Narratives Tobias Pischel de Ascensão Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft der Universität Osnabrück Hauptberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Oliver Grannis Nebenberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Busse Osnabrück, 01.12.2003 Contents i Contents List of Tables iii List of Figures iv Conventions and abbreviations v Preface vi 0. Introduction: the slave narrative as an object of linguistic study 1 1. Slavery, resistance and the slave narrative 6 1.1 Slavery and resistance 6 1.2 The development of the slave narrative 12 1.2.1 The first phase 12 1.2.2 The second phase 15 1.2.3 The slave narrative after 1865 21 2. Discourse, power, and ideology in the slave narrative 23 2.1 The production of disciplinary knowledge 23 2.2 Truth, reality, and ideology 31 2.3 “The writer” and “the reader” of slave narratives 35 2.3.1 Slave narrative production: “the writer” 35 2.3.2 Slave narrative reception: “the reader” 39 3. The language of slave narratives as an object of study 42 3.1 Investigations in the language of the slave narrative 42 3.2 The “plain-style”-fallacy 45 3.3 Linguistic expression as functional choice 48 3.4 The construal of experience and identity 51 3.4.1 The ideational metafunction 52 3.4.2 The interpersonal metafunction 55 3.4.3 The textual metafunction 55 3.5 Applying systemic grammar 56 4. -

Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, James, "Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution" (2015). Masters Theses. 23. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/23 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory as Torchlight: Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2015 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: The Antebellum Era………………………………………………………….22 Chapter 2: Secession and the Civil War…………………………………………………66 Chapter 3: Reconstruction and the Post-War Years……………………………………112 Epilogue………………………………………………………………………………...150 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………154 ii Abstract The following explores how Frederick Douglass used memoires of the Haitian Revolution in various public forums throughout the nineteenth century. Specifically, it analyzes both how Douglass articulated specific public memories of the Haitian Revolution and why his articulations changed over time. Additional context is added to the present analysis as Douglass’ various articulations are also compared to those of other individuals who were expressing their memories at the same time. -

Community and Status of the African American Slave Population at Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina Amy C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 The Affinities and Disparities within: Community and Status of the African American Slave Population at Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, Mount Pleasant, South Carolina Amy C. Kowal Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE AFFINITIES AND DISPARITIES WITHIN: COMMUNITY AND STATUS OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SLAVE POPULATION AT CHARLES PINCKNEY NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE, MOUNT PLEASANT, SOUTH CAROLINA By AMY C. KOWAL A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 Copyright © 2007 Amy C. Kowal All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Amy C. Kowal defended on December 14, 2006. ____________________________ Glen H. Doran Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________ Dennis Moore Outside Committee Member ____________________________ Joseph Hellweg Committee Member ____________________________ Bennie C. Keel Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________________ Dean Falk, Chair, Department of Anthropology _____________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to Bill Kowal for all his love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge the significant influence and exemplar of several people. My advisor through both my masters and doctorate education is Glen H. Doran. His advice and encouragement throughout my graduate education has been invaluable. I am thankful for his offers of assistance and collaboration on his projects. -

Transatlantica, 1 | 2018 Confronting Race Head-On in 12 Years a Slave (Steve Mcqueen, 2013): Redefinin

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2018 Slavery on Screen / American Women Writers Abroad: 1849-1976 Confronting Race Head-on in 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013): Redefining the Contours of the Classic Biopic? Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/11593 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.11593 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher AFEA Electronic reference Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris, “Confronting Race Head-on in 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013): Redefining the Contours of the Classic Biopic?”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2018, Online since 05 September 2019, connection on 29 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/ 11593 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.11593 This text was automatically generated on 29 April 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Confronting Race Head-on in 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013): Redefinin... 1 Confronting Race Head-on in 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013): Redefining the Contours of the Classic Biopic? Anne-Marie Paquet-Deyris 1 During the Obama years, the issue of race seemed to dissolve into the so-called “post- racial” era in the media. For critics such as H. Roy Kaplan in The Myth of Post-Racial America: Searching for Equality in the Age of Materialism (2011) and David J. Leonard and Lisa A. Guerrero in African Americans on Television: Race-ing for Ratings (2013), however, such colorblindness led to the bypassing of any direct confrontation with the persistent problems linked to race in contemporary American society.