Rochester's Frederick Douglass, Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Founding and Early Years of the National Association of Colored Women

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-20-1977 The Founding and Early Years of the National Association of Colored Women Therese C. Tepedino Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Tepedino, Therese C., "The Founding and Early Years of the National Association of Colored Women" (1977). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2504. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2498 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF 'IRE THESIS OF Therese C. Tepedino for the Master of Arts in History presented May 20, 1977. Title: The Founding and Early Years of the National Association of Colored Women. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: : • t. : The National Association of Colored Women was formed in 1896, during a period when the Negro was encountering a great amount of difficulty in maintaining the legal and political rights granted to him during the period of recon~ struction. As a result of this erosion· of power, some historians have contended that the Negro male was unable to effectively deal with the problems that arose within the Negro community. It was during this same period of time that the Negro woman began to assert herself in the affairs of her community. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

An American Slave: Frederick Douglass and the Importance of His Narratives

An American Slave: Frederick Douglass and the Importance of His Narratives Pavić, Andrea Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:606265 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-01 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major MA Study Programme in English Language and Literature –Teaching English as a Foreign Language and German Language and Literature –Teaching German as a Foreign Language Andrea Pavić An American Slave: Frederick Douglass and the Importance of His Narratives Master's Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Jadranka Zlomislić, Assistant Professor Osijek, 2018 J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Study Programme: Double Major MA Study Programme in English Language and Literature –Teaching English as a Foreign Language and German Language and Literature –Teaching German as a Foreign Language Andrea Pavić An American Slave: Frederick Douglass and the Importance of His Narratives Master's Thesis Scientific area: humanities Scientific field: philology Scientific branch: English studies Supervisor: Dr. Jadranka Zlomislić, Assistant Professor Osijek, 2018 Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i njemačkog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Andrea Pavić Američki rob: Frederick Douglass i važnost njegovih pripovijesti Diplomski rad Mentor: doc. -

And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass As a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Theology Faculty Publications Theology 10-1988 And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass as a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895 Gabriel Pivarnik Providence College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_fac Part of the Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Pivarnik, Gabriel, "And He Was No Soft-Tongued Apologist: Fredrick Douglass as a Constitutional Theorist 1865-1895" (1988). Theology Faculty Publications. 5. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/theology_fac/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AND HE WAS NO SOFT-TONGUED APOLOGIST: FREDERICK DOUGLASS AS A CONSTITUTIONAL THEORIST, 1865-1895 A Paper Presented to the National Endowment for the Humanities for the Younger Scholars Grant Program 1988 by Robert George Pivarnik October, 1988 And he was no soft-tongued apologist; He spoke straightforward, fearlessly uncowed The sunlight of his truth dispelled the mist, And set in bold relief each dark-hued cloud; To sin and crime he gave their proper hue, And hurled at evil what was evil's due. Paul Lawrence Dunbar, "Frederick Douglass" Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the work of Waldo E. Martin on the psychology of Frederick Douglass. If it were not for Martin's research, this project would never have gotten underway. I would also like to thank Elizabeth Ackert and the staff of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Library who were instrumen tal in helping me obtain the necessary resources for this work. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Purchasing Frederick Douglass's Freedom in 1846 Hannah-Rose

New North Star, 2020; 2:63–65 “The Birth Place of Your Liberty”: Purchasing Frederick Douglass’s Freedom in 1846 Hannah-Rose Murray University of Edinburgh Following in the footsteps of African Americans who had made radical and politicized journeys across the Atlantic, Frederick Douglass set sail for the British Isles in August 1845. Over the course of nearly two years, he electrified audiences with his blistering exposure of American slavery, the corruption and pollution of Southern Christianity, and the blatant hypocrisies of American freedom and independence. He forged antislavery networks with British and Irish abolitionists who would support him financially and emotionally for the rest of his life, including most famously Julia Griffiths Crofts, Russell L. and Mary Carpenter, and Ellen and Anna Richardson, who were based in Newcastle. After a stay in the Richardson household in 1846, Ellen became determined to secure Douglass’s legal freedom; extended analysis of her letters, though, indicates that throughout the entire process she did not discuss the matter with him. Through Walter Lowrie, a lawyer in New York, she and her sister-in-law Anna made contact with Douglass’s enslaver, Hugh Auld, and organized a bill of sale for £150, or $750. Eventually, on 12 December 1846, the free papers were signed.1 While Douglass regarded this as a generous and unselfish act throughout his life, supporters of William Lloyd Garrison and the American Anti- Slavery Society objected to the purchase, for it seemed to be `property.2 In the pages of the -

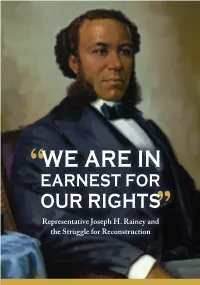

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

Frederick Douglass As a U.S

LATER LIFE 0. LATER LIFE - Story Preface 1. A CHILD SLAVE 2. GET EDUCATED!! 3. ESCAPE! 4. ANNA MURRAY DOUGLASS 5. THE ABOLITIONISTS 6. ABOLITIONIST LITERATURE 7. FAME 8. DOUGLASS AT HOME 9. LATER LIFE 10. DEATH AND LEGACY This drawin—published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper on April 7, 1877 (at page 85)—shows Frederick Douglass as a U.S. Marshall. Online, courtesy Library of Congress. In 1881, Frederick was invited to the inauguration of President Garfield (who was assassinated a few months later). While chief executive, Garfield made Douglass recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia. Working in the recorder’s office was a white woman named Helen Pitts. In 1884, she became the second Mrs. Douglass. An article, published after Frederick died, provides the background of their romance: The story of the second marriage was a romantic one. Miss Helen Pitts, whom he married, was a New England woman of middle age, a clerk in the office of the Recorder of Deeds of the District of Columbia, when Mr. Douglass was appointed to that office. She was a member of a literary society to which he belonged. They were thrown much together, and finally became engaged. Her relatives opposed the union bitterly on account of his color, but finally yielded to force of circumstances. Frederick reportedly said: “My first wife was the color of my mother, my second is the color of my father.” According to contemporary articles, however, his children also opposed the marriage. During the last years of his life, he was known as “The Old Man Eloquent,” and lived with Helen at Cedar Hill, his home in the eastern outskirts of D.C. -

Sample Proposal for Workshop

Nancy I. Sanders Street Address City, state, zip phone number e-mail address website address Frederick Douglass for Kids With 21 Activities Sample Manuscript and Activity Table of Contents Chapter 1: Four Score and Seven Years Ago… • Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey is born into slavery in Maryland in 1817. • Brief history of slavery and free African American leaders during the founding years of our nation. • Anna Murray (future wife of Frederick Douglass) is born free just after parents are freed from slavery. • Frederick Bailey’s life as a slave. He teaches himself to read after learning his letters from Sophia Auld, who broke the law by teaching a slave. o Activity: Help a younger child learn to read. Sanders-Douglass 2 • Anna Murray moves to Baltimore, Maryland and finds work as a house servant. • Robert Roberts publishes The House Servant’s Directory: An African American Butler’s 1827 Guide. Include excerpt on how a servant such as Anna Murray would serve tea and coffee to a room full of guests. o Activity: Recipe house servants used for making a paste that can be set in room to keep flies away. • Anna Murray is active in her church and various self-improvement societies. Anna meets Frederick through a debating club. o Activity: Form a debating club. • Frederick reads newspaper article about John Quincy Adam’s work as an abolitionist and learns about organized efforts to stop slavery. • Attempting to teach other slaves to read, Frederick is discovered and stopped. • Frederick works in Baltimore shipyards and is a ship’s caulker. o Activity: Make a caulking wheel and learn how a ship was caulked. -

In the Library Frederick Douglass Family Materials from the Walter O

In the Library Frederick Douglass Family Materials from the Walter O. Evans Collection April 22 – June 14, 2019 National Gallery of Art Dr. Walter O. Evans and Linda Evans at their home in Savannah, Georgia, 2009. Courtesy Walter O. Evans. Frederick Douglass Family Materials from the Walter O. Evans Collection “I hope that in some small way my collecting will encourage others to do the same, and to recognize the importance of preserving our cultural heritage, providing a legacy for those who come after us.” – Dr. Walter O. Evans Walter O. Evans has spent decades collecting, curating, and conserving a wide variety of African American art, music, and literature in an effort to preserve the cultural history of African Americans. His home in Savannah, Georgia, is a repository of the artworks and papers of many important figures, and increasingly has become a destination for scholars. Part of his collection focuses on the nineteenth-century slave, abolitionist, and statesman Frederick Douglass (c. 1818 – 1895). In addition to inscribed books from Douglass’s and his descendants’ libraries and printed editions of his speeches, the collection contains letters, manuscripts, photographs, and scrapbooks. While some of this material relates directly to Douglass’s speeches and work promoting the cause of black freedom and equality, much of the material is of a more personal nature: correspondence between family members, family histories, and scrapbooks compiled by Douglass and his sons Lewis Henry, Charles Remond, and Frederick Douglass Jr. This family history provides a new lens through which to view the near-mythical orator. In addition to containing news clippings from many nineteenth-century African American newspapers that do not survive in other archives today, the scrapbooks, with their personal documents and familial relationships, illuminate Frederick Douglass in ways never before seen. -

Douglass: in His Own Time

Civil War Book Review Spring 2015 Article 7 Douglass: In His Own Time Leigh Fought Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Fought, Leigh (2015) "Douglass: In His Own Time," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.17.2.08 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol17/iss2/7 Fought: Douglass: In His Own Time Review Fought, Leigh Spring 2015 Ernest, John Douglass: In His Own Time. University of Iowa Press, $37.50 ISBN 9781609382803 Frederick Douglass through the Eyes of His Contemporaries With Douglass in His Own Time, editor and scholar of African American literature John Ernest intends to provide an “introduction to Douglass the man by those who knew him" (p. ix). Attempting to avoid selections that reiterate Douglass’s own accounts of his life, Ernest chooses fifty-two documents dated from between 1841 and 1914 that emphasize themes of race, politics, and religion. For lay readers with little knowledge of Douglass’s life, this volume will likely accomplish its intended task, although anyone hoping for the title’s promises of “recollections, interviews, and memoirs" from family will be wholly disappointed. Those who do know something of Douglass’s life, however, may be perplexed by the selection of these particular documents and the omission of those that might better illustrate many of the points addressed in Ernest’s introduction. A collection such as this could serve as a valuable compliment to the volumes of The Frederick Douglass Papers Project, which publishes only Douglass’s writings and correspondence and intentionally excludes epistolary conversations about the great man by third parties. -

Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, James, "Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution" (2015). Masters Theses. 23. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/23 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory as Torchlight: Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2015 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: The Antebellum Era………………………………………………………….22 Chapter 2: Secession and the Civil War…………………………………………………66 Chapter 3: Reconstruction and the Post-War Years……………………………………112 Epilogue………………………………………………………………………………...150 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………154 ii Abstract The following explores how Frederick Douglass used memoires of the Haitian Revolution in various public forums throughout the nineteenth century. Specifically, it analyzes both how Douglass articulated specific public memories of the Haitian Revolution and why his articulations changed over time. Additional context is added to the present analysis as Douglass’ various articulations are also compared to those of other individuals who were expressing their memories at the same time.