Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Helot Revolt of Sparta Greece

464 B.C. The Helot Revolt of Sparta Greece Sparta, at first, was only the Messenia and Laconia territories, and later the Spartans (previously known as the Dorians) came and took over those territories. Those places they conquered had other residents who were captured and used them as Spartan “slaves” (also known as Helots) for the growing nation. However, these Helots were not the property of anyone or under the control of a specific person. They worked for Sparta in general, and since the Dorians couldn’t do agriculture, they made the Helots do the work. The Dorians were “Barbarians,” note them taking over territories. Unlike the slaves that we know today, these ones were able to go wherever they want in Spartan territory and they could live normal lives like the Spartans.The Helots lived in houses together for a plot of land that they worked on. They were allowed families, to go away from their house and make cash for themselves. Occasionally, the Helots would be assigned to help out in the military. However, not all Helots were happy where they were at. Around 660 B.C., the Spartans attacked the Argives, who demolished the Spartans. The report of Sparta’s lost gave encouragement to the Helots who started a revolt against Sparta, which is now known as the Second Messenian War. The Spartans were fighting to gain back control, but they were outnumbered seven Helots to one Spartan. The details about this war were concealed, and very little information is known about what happened in the war. -

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery Siobhán McGrath Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science, New School University Economic Development & Global Governance and Independent Study: William Milberg Spring 2005 1. Introduction It is widely accepted that capitalism is characterized by “free” wage labor. But what is “free wage labor”? According to Marx a “free” laborer is “free in the double sense, that as a free man he can dispose of his labour power as his own commodity, and that on the other hand he has no other commodity for sale” – thus obliging the laborer to sell this labor power to an employer, who possesses the means of production. Yet, instances of “unfree labor” – where the worker cannot even “dispose of his labor power as his own commodity1” – abound under capitalism. The question posed by this paper is why. What factors can account for the existence of unfree labor? What role does it play in an economy? Why does it exist in certain forms? In terms of the broadest answers to the question of why unfree labor exists under capitalism, there appear to be various potential hypotheses. ¾ Unfree labor may be theorized as a “pre-capitalist” form of labor that has lingered on, a “vestige” of a formerly dominant mode of production. Similarly, it may be viewed as a “non-capitalist” form of labor that can come into existence under capitalism, but can never become the central form of labor. ¾ An alternate explanation of the relationship between unfree labor and capitalism is that it is part of a process of primary accumulation. -

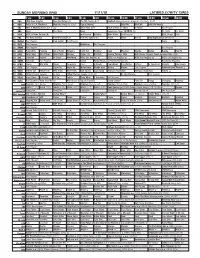

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Slavery, Property, Sexual Hierarchy

Politics, Book I: Slavery, Property, Sexual Hierarchy PHIL 2011 2010-11 1 ‘All men are created equal…’ An impossible thought for ancient thinkers 2 Hierarchy of Beings • Hierarchy is natural (Pol., I, passim); – = relations of super- and subordination – Master-slave; male-female (esp. p. 17, Pol. 1.5). • Each being has its own kind of soul (anima): – not to be confused w/ Christian idea of soul; • Plants: vegetative soul; stays in one place, serve animals; • Animals: sensitive soul; have locomotion • Humans: rational soul, locomotion, activity • Higher vs lower humans: – those who have the capacity to rule: • statesmen, men in general, and Greeks. – Those who need to be ruled • natural slaves, women/wives, and barbarians. 3 4 A base instrument: the Auloi [Pipes] 5 Actual Slavery Status Sources of slaves • No rights; • Birth • Property of master, who could • Purchase kill or punish in any way he • Conquest/War wished; • Criminal conviction; in Athens • Law required slaves to be this meant being sent to the tortured when giving evidence; silver mines, where death was • Manumission (grant of certain; freedom) rare in ancient • The reality was different from Greece, common in Rome. Aristotle’s theory! • Worshipped master’s family gods (ancestors) • Given a name. 6 Elaboration on ancient slavery In Athens Elsewhere • Domestic servitude: • ‘Helotage’: enslaved – Debated and codified communities, – Personal dependence – e.g. Sparta’s Helots – Essential element of oikos (household) – retained identity, customs, – Manumission rare & contracts gods, etc offered few advantages – Similar idea in Pol. 7.10. – Closed system—did not offer passage to citizenship. • Roman manumission; • Penal slavery= certain death – strategically created • Public slavery, patron-client networks; – e.g. -

Julia Faisst, Phin Beiheft

PhiN Beiheft | Supplement 5/2012: 71 Julia Faisst (Siegen) Degrees of Exposure: Frederick Douglass, Daguerreotypes, and Representations of Freedom1 This essay investigates the picture-making processes in the writings of Frederick Douglass, one of the most articulate critics of photography in the second half of the nineteenth century. Through his fiction, speeches on photography, three autobiographies, and frontispieces, he fashioned himself as the most "representative" African American of his time, and effectively updated and expanded the image of the increasingly emancipated African American self. Tracing Douglass's project of self-fashioning – both of himself and his race – with the aid of images as well as words is the major aim of this essay. Through a close reading of the historical novella "The Heroic Slave," I examine how the face of a slave imprints itself on the photographic memory of a white man as it would on a silvered daguerreotype plate – transforming the latter into a committed abolitionist. The essay furthermore uncovers how the transformation of the novella's slave into a free man is described in terms of various photographic genres: first a "type," Augustus Washington (whose life story mirrors that of Douglass) changes into a subject worthy of portraiture. As he explored photographic genres in his writings, Douglass launched the genre of African American fiction. Moreover, through his pronounced interest in mixed media, he functioned as an immediate precursor to modernist authors who produced literature on the basis of photographic imagery. Overall, this essay reveals how Douglass performed his own progress within his photographically inflected writings, and turned both himself and his characters into free people. -

Religion and the Abolition of Slavery: a Comparative Approach

Religions and the abolition of slavery - a comparative approach William G. Clarence-Smith Economic historians tend to see religion as justifying servitude, or perhaps as ameliorating the conditions of slaves and serving to make abolition acceptable, but rarely as a causative factor in the evolution of the ‘peculiar institution.’ In the hallowed traditions, slavery emerges from scarcity of labour and abundance of land. This may be a mistake. If culture is to humans what water is to fish, the relationship between slavery and religion might be stood on its head. It takes a culture that sees certain human beings as chattels, or livestock, for labour to be structured in particular ways. If religions profoundly affected labour opportunities in societies, it becomes all the more important to understand how perceptions of slavery differed and changed. It is customary to draw a distinction between Christian sensitivity to slavery, and the ingrained conservatism of other faiths, but all world religions have wrestled with the problem of slavery. Moreover, all have hesitated between sanctioning and condemning the 'embarrassing institution.' Acceptance of slavery lasted for centuries, and yet went hand in hand with doubts, criticisms, and occasional outright condemnations. Hinduism The roots of slavery stretch back to the earliest Hindu texts, and belief in reincarnation led to the interpretation of slavery as retribution for evil deeds in an earlier life. Servile status originated chiefly from capture in war, birth to a bondwoman, sale of self and children, debt, or judicial procedures. Caste and slavery overlapped considerably, but were far from being identical. Brahmins tried to have themselves exempted from servitude, and more generally to ensure that no slave should belong to 1 someone from a lower caste. -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

Sinner to Saint

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:54 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of November 11 - 17, 2017 OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Sinner to saint FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Kimberly Hébert Gregoy and Jason Ritter star in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World” Massachusetts’ First Credit Union In spite of his selfish past — or perhaps be- Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle cause of it — Kevin Finn (Jason Ritter, “Joan of St. Jean's Credit Union INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY Arcadia”) sets out to make the world a better 3 x 3 Voted #1 1 x 3 place in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World,” Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 Insurance Agency airing Tuesday, Nov. 14, on ABC. All the while, a Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs celestial being known as Yvette (Kimberly Hé- bert Gregory, “Vice Principals”) guides him on Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses Auto • Homeowners his mission. JoAnna Garcia Swisher (“Once 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business • Life Insurance Upon a Time”) and India de Beaufort (“Veep”) Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere 978-777-6344 also star. Federally Insured by NCUA www.doyleinsurance.com FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:55 PM 2 • Salem News • November 11 - 17, 2017 TV with soul: New ABC drama follows a man on a mission By Kyla Brewer find and anoint a new generation the Hollywood ranks with roles in With You,” and has a recurring role ma, but they hope “Kevin (Proba- TV Media of righteous souls. -

When Sons Remember Their Fathers

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History Winter 1997 When Sons Remember Their Fathers Bruce Dorsey Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Bruce Dorsey. (1997). "When Sons Remember Their Fathers". Kenyon Review. Volume 19, Issue 1. 162-166. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/120 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRUCE DORSEY WHEN SONS REMEMBER THEIR FATHERS Fathering the Nation: American Genealogies of Slavery and Freedom. By Russ Castronovo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. 295 pp. $32.00. Over the past half decade, historians of American culture have been attracted to two quite disparate avenues of inquiry, one involving a heightened understanding of memory and the second expanding the parameters of gender to include the meanings of masculinity. Certainly the mythic and cultural significance of the "Founding Fathers" for a generation of Americans on the eve of the Civil War offers a rich field for exploring both of these. An understanding of the "Founding Fathers" demands an analysis of the relationships between fathers and sons (both real and metaphorical) as well as the manner in which different antebellum Americans constructed -

AREA RESTAURANT GUIDE American Café O'charley's Homestead Restaurant Mcdonald's 306 S Ewing St

B4 Thursday, March 22, 2012 | TV | www.kentuckynewera.com THURSDAY PRIMETIME MARCH 22, 2012 N - NEW WAVE M - MEDIACOM S1 - DISH NETWORK S2 - DIRECTV N M 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 1:30 S1 S2 :35 :05 :35 :35 (2) (2) WKRN [2] Nashville's Nashville's Nashville's ABC World Nashville's Wheel of Missing "The Hard Grey's Anatomy "If/ Private Practice "It Nashville's News Jimmy Kimmel Live Extra Law & Order: C.I. Paid ABC News 2 News 2 News 2 News News 2 Fortune Drive" (N) Then" Was Inevitable" (N) News 2 "Privilege" Program 2 2 :35 :35 :35 :05 (4) WSMV [4] Channel 4 Channel 4 Channel 4 NBC News Channel 4 Channel 4 Commu- 30 Rock 30 Rock Up All Awake "Kate Is Channel 4 Jay Leno Arsenio LateNight Fallon Carson Today Show NBC News News News 5 News nity (N) Night (N) Enough" (N) News Hall, Lily Collins (N) Candice Bergen, Fergie Daly 4 4 :35 :35 :35 (5) (5) WTVF [5] News 5 Inside News 5 CBSNews NCAA Basketball Division I Tournament West Region Sweet NCAA Basketball Division I Tournament West Region Sweet News 5 David Letterman LateLate Show Frasier CBS Edition Sixteen (L) Sixteen (L) Ewan McGregor 5 5 :35 :35 :35 :05 (6) (6) WPSD Dr. Phil Local 6 at NBC News Local 6 at Wheel of Commu- 30 Rock 30 Rock Up All Awake "Kate Is Local 6 at Jay Leno Arsenio LateNight Fallon Carson Today Show NBC 5 p.m. -

1. Slavery, Resistance and the Slave Narrative

“I have often tried to write myself a pass” A Systemic-Functional Analysis of Discourse in Selected African American Slave Narratives Tobias Pischel de Ascensão Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft der Universität Osnabrück Hauptberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Oliver Grannis Nebenberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Busse Osnabrück, 01.12.2003 Contents i Contents List of Tables iii List of Figures iv Conventions and abbreviations v Preface vi 0. Introduction: the slave narrative as an object of linguistic study 1 1. Slavery, resistance and the slave narrative 6 1.1 Slavery and resistance 6 1.2 The development of the slave narrative 12 1.2.1 The first phase 12 1.2.2 The second phase 15 1.2.3 The slave narrative after 1865 21 2. Discourse, power, and ideology in the slave narrative 23 2.1 The production of disciplinary knowledge 23 2.2 Truth, reality, and ideology 31 2.3 “The writer” and “the reader” of slave narratives 35 2.3.1 Slave narrative production: “the writer” 35 2.3.2 Slave narrative reception: “the reader” 39 3. The language of slave narratives as an object of study 42 3.1 Investigations in the language of the slave narrative 42 3.2 The “plain-style”-fallacy 45 3.3 Linguistic expression as functional choice 48 3.4 The construal of experience and identity 51 3.4.1 The ideational metafunction 52 3.4.2 The interpersonal metafunction 55 3.4.3 The textual metafunction 55 3.5 Applying systemic grammar 56 4. -

Gibbs's Rules

Gibbs's Rules THIS SITE USES COOKIES Gibbs's Rules are an extensive series of guidelines that NCIS Special Agent Leroy Jethro Gibbs lives by and teaches to the people he works closely with. FANDOM and our partners use technology such as cookies on our site to personalize content and ads, provide social media features, and analyze our traffic. In particular, we want to draw your attention to cookies which are used to market to you, or provide personalized ads to you. Where we use these cookies (“advertising cookies”), we do so only where you have consented to our use of such cookies by ticking Contents [show] "ACCEPT ADVERTISING COOKIES" below. Note that if you select reject, you may see ads that are less relevant to you and certain features of the site may not work as intended. You can change your mind and revisit your consent choices at any time by visiting our privacy policy. For more information about the cookies we use, please see our Privacy Policy. For information about our partners using advertising cookies on our site, please see the Partner List below. Origins It was revealed in the last few minutes of the Season 6 episode, Heartland (episode) that Gibbs's rules originated from his first AwCifCeE, SPhTa AnDnVoEn RGTibISbIsN,G w CheOrOeK sIhEeS told him at their first meeting that "Everyone needs a code they can live by". The only rule of Shannon's personal code that is quoted is either her first or third: "Never date a lumberjack." REJECT ADVERTISING COOKIES Years later, after their wedding, Gibbs began writing his rules down, keeping them in a small tin inside his home which was shown in the Season 7 finale episode, Rule Fifty-One (episode).