The Historical Legacies of the Polish Partitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland and the UK – a Comparative Study Term: Autumn

Springwood School Medium Term Planning Topic: Poland and the UK – a comparative study Term: Autumn Pre Formal Semi Formal Formal Suggested Activities Suggested Activities Suggested Activities 1 Experience a range of foods from Poland and Explore and recognise a range of foods from Investigate different Traditional UK and the UK. Record responses and likes/dislikes. Poland and the UK. Polish foods. Discuss and understand the Food similarities and differences. Explore a range of foods from Poland and the Taste a range of traditional Polish and UK dishes. UK with our senses – smell, touch and taste. Use a variety of ways to communicate to show Use a range of traditional Polish and UK foods Observe and record responses and likes/dislikes. as a basis for different activities. likes/dislikes. Use traditional ingredients to make items from Investigate which foods are traditional Polish Make a range of traditional Polish or UK foods both countries that are similar, eg traditional and traditional UK, particularly linked to that are sensory in nature– compare and soup – compare and contrast. Christmas. contrast, eg breads. Explore different foods that are traditionally Design a traditional UK or traditional Polish Link to traditional foods that are eaten during eaten at Christmas in both countries. Use as a menu. Christmas time in both countries – taste, basis for writing and creative work. touch, smell a range of these foods. Visit a local Polish food shop to investigate Make own representations through cookery Set up a role play café area in class linked to both the type of foods that are traditionally eaten. -

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

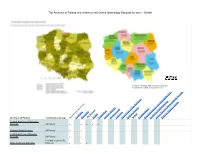

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

Human Capital in the Aftermath of the Partitions of Poland Andreas Ba

European Historical Economics Society EHES Working Paper | No. 150 | March 2019 Fading Legacies: Human Capital in the Aftermath of the Partitions of Poland Andreas Backhaus, Centre for European Policy Studies EHES Working Paper | No. 150 | March 2019 Fading Legacies: Human Capital in the Aftermath of the Partitions of Poland* Andreas Backhaus†, Centre for European Policy Studies Abstract This paper studies the longevity of historical legacies in the context of the formation of human capital. The Partitions of Poland (1772-1918) represent a natural experiment that instilled Poland with three different legacies of education, resulting in sharp differences in human capital among the Polish population. I construct a large, unique dataset that reflects the state of schooling and human capital in the partition territories from 1911 to 1961. Using a spatial regression discontinuity design, I find that primary school enrollment differs by as much as 80 percentage points between the partitions before WWI. However, this legacy disappears within the following two decades of Polish independence, as all former partitions achieve universal enrollment. Differences in educational infrastructure and gender access to schooling simultaneously disappear after WWI. The level of literacy converges likewise across the former partitions, driven by a high intergenerational mobility in education. After WWII, the former partitions are not distinguishable from each other in terms of education anymore. JEL Codes: N34, I20, O15, H75 Keywords: Poland, Human Capital, Education, Persistence * Research for this paper was conducted while the author was a Ph.D. candidate at LMU Munich. The author would like to thank Philipp Ager, Lukas Buchheim, Matteo Cervellati, Jeremiah Dittmar, Erik Hornung, Chris Muris, Christian Ochsner, Uwe Sunde, Ludger Wößmann, Nikolaus Wolf, and audiences at the University of Southern Denmark, the University of Bayreuth, UCLouvain, the FRESH Meeting 2018, the WEast Workshop 2018, and WIEM 2018 for their comments. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context, C.1500–1795

The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context, c.1500–1795 The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context, c.1500–1795 Edited by Richard Butterwick Lecturer in Modern European History Queen’s University Belfast Northern Ireland Editorial matter, selection and Introduction © Richard Butterwick 2001 Chapter 10 © Richard Butterwick 2001 Chapters 1–9 © Palgrave Publishers Ltd 2001 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2001 978-0-333-77382-6 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2001 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin’s Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd). ISBN 978-1-349-41618-9 ISBN 978-0-333-99380-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780333993804 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Eastern Poland As the Borderland of the European Union1

QUAESTIONES GEOGRAPHICAE 29(2) • 2010 EASTERN POLAND AS THE BORDERLAND OF THE EUROPEAN UNION1 TOMASZ KOMORNICKI Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland ANDRZEJ MISZCZUK Centre for European Regional and Local Studies EUROREG, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland Manuscript received May 28, 2010 Revised version June 7, 2010 KOMORNICKI T. & MISZCZUK A., Eastern Poland as the borderland of the European Union. Quaestiones Geo- graphicae 29(2), Adam Mickiewicz University Press, Poznań 2010, pp. 55-69, 3 Figs, 5 Tables. ISBN 978-83-232- 2168-5. ISSN 0137-477X. DOI 10.2478/v10117-010-0014-5. ABSTRACT. The purpose of the present paper is to characterise the socio-economic potentials of the regions situated on both sides of the Polish-Russian, Polish-Belarusian and Polish-Ukrainian boundaries (against the background of historical conditions), as well as the economic interactions taking place within these regions. The analysis, carried out in a dynamic setting, sought to identify changes that have occurred owing to the enlargement of the European Union (including those associated with the absorption of the means from the pre-accession funds and from the structural funds). The territorial reach of the analysis encompasses four Polish units of the NUTS 2 level (voivodeships, or “voivodeships”), situated directly at the present outer boundary of the European Union: Warmia-Mazuria, Podlasie, Lublin and Subcarpathia. Besides, the analysis extends to the units located just outside of the eastern border of Poland: the District of Kaliningrad of the Rus- sian Federation, the Belarusian districts of Hrodna and Brest, as well as the Ukrainian districts of Volyn, Lviv and Zakarpattya. -

Poland Historical Geography Handout

Poland Historical Geography: Polish History through Maps and Gazetteers Daniel R. Jones, MS, AG® FamilySearch HISTORY OF POLAND Polish Commonwealth, 1600s-1795 Instead of a hereditary monarchy, they elected their own king. Because the king was elected, this allowed foreign powers to manipulate the elections for candidates, and to create turmoil for their own gain. The commonwealth was in a state of decline because of wars, political turmoil, and aristocratic rebellions. Although reforms were attempted, Poland’s neighbors saw opportunities for themselves. Partitions of Poland, 1772-1795 First partition, 1772: Rebellion occurred in 1768, bringing Poland into a civil war. Austria, Prussia, and Russia collectively decided to annex pieces of Poland for themselves during the war. Second partition, 1792: Poland institutes a constitution in 1791. This angered Russia, who encouraged another rebellion against the Polish king. Russia provided military support to the rebellion. After a few months, Russia and Prussia slice off large sections of Poland. Third partition, 1795: Some nobles were angry at their king for surrendering to Russia during the second partition, and created another uprising. Russia invaded again to crush the uprising. Russia, Austria, and Prussia decided to split the rest of Poland between themselves, and Poland disappeared off the map. Kingdom of Poland, 1815-1914 The French created the Duchy of Warsaw during the Napoleonic Wars as a semi-independent country. After the war, the Kingdom of Poland was established, but was joined to the Russian Empire; they were allowed their own constitution and military. After several uprisings, the Polish language and culture were suppressed, the kingdom was more integrated into the Russian Empire. -

221 Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis

221 Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis Studia Geographica X Redaktor Naczelny ZastępcaSławomir RedaktoraKurek Naczelnego RadaTomasz Programowa Rachwał Gideon Biger (Tel Aviv University, Izrael), Zbigniew Długosz (Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny, Kraków), Anatol- Jakobson (Irkutsk University, Rosja), Sławomir Kurek (Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny, Kraków) – Chair, Ana María Liberali (Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentyna), Roman Malarz (Uniwersytet Peda gogiczny, Kraków), Keisuke Matsui (University of Tsukuba, Japonia), Aleksandar Petrovic (University of- Belgrade, Serbia), Tomasz Rachwał (Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny, Kraków) – Vice-chair, Natalia M. Sysoeva (Irkutsk University, Rosja), Zdeněk Szczyrba (Univerzita Palackeho v Olomouci, Czechy), Wanda Wil- czyńska-Michalik (Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny, Kraków), Witold Wilczyński (Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny, Kraków), Bożena Wójtowicz (Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny, Kraków), Mirosław Wójtowicz (Uniwersytet Pe dagogiczny, Kraków), Jiuchen Zhang (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chiny), Zbigniew Zioło (Podkarpacka ListaSzkoła recenzentów Wyższa im. bł. ks. Władysława Findysza, Jasło) - Krystyna German (Uniwersytet Jagielloński), Zygmunt Górka (Uniwersytet Jagielloński), Jerzy Kitowski (Uniwersytet Rzeszowski), Tomasz Komornicki (Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej, Lublin), Włodzi mierz Kurek (Uniwersytet Jagielloński), Rene Matlovic (Presovska Univerzita v Presove, Słowacja), Piotr Pachura (Politechnika Częstochowska), Joanna Pociask-Karteczka (Uniwersytet Jagielloński), Zbigniew Podgórski (Uniwersytet -

Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego W Warszawie W „Akcji Łączności Fabryk (Miasta) Z Wsią” W Latach 1949–1954

SPORT I TURYSTYKA ŚRODKOWOEUROPEJSKIE CZASOPISMO NAUKOWE T. 3 NR 4 RADA NAUKOWA Ryszard ASIENKIEWICZ (Uniwersytet Zielonogórski) Diethelm BLECKING (Uniwersytet Albrechta i Ludwika we Fryburgu) Miroslav BOBRIK (Słowacki Uniwersytet Techniczny w Bratysławie) Valentin CONSTANTINOV (Uniwersytet Państwowy Tiraspol z siedzibą w Kiszyniowie) Tomáš DOHNAL (Uniwersytet Techniczny w Libercu) Elena GODINA (Rosyjski Państwowy Uniwersytet Wychowania Fizycznego, Sportu i Turystyki) Karol GÖRNER (Uniwersytet Mateja Bela w Bańskiej Bystrzycy) Wiktor Władimirowicz GRIGORIEWICZ (Grodzieński Państwowy Uniwersytet Medyczny) Michal JIŘÍ (Uniwersytet Mateja Bela w Bańskiej Bystrzycy) Tomasz JUREK (Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego im. Eugeniusza Piaseckiego w Poznaniu) Jerzy KOSIEWICZ (Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego Józefa Piłsudskiego w Warszawie) Jurij LIANNOJ (Sumski Państwowy Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny im. Antona Makarenki) Wojciech LIPOŃSKI (Uniwersytet Szczeciński) Veaceslav MANOLACHI (Państwowy Uniwersytet Wychowania Fizycznego i Sportu w Kiszyniowie) Josef OBORNÝ (Uniwersytet Komeńskiego w Bratysławie) Andrzej PAWŁUCKI (Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego we Wrocławiu) Jurij PELEKH (Równieński Państwowy Uniwersytet Humanistyczny) Gertrud PFISTER (Uniwersytet Kopenhaski) Anatolij TSOS (Wschodnioeuropejski Narodowy Uniwersytet im. Łesi Ukrainki w Łucku) Marek WAIC (Uniwersytet Karola w Pradze) Klaudia ZUSKOVÁ (Uniwersytet Pavla Jozefa Šafárika w Koszycach) LISTA RECENZENTÓW prof. apl. dr. Diethelm BLECKING; dr prof. nadzw. Valentin CONSTANTINOV; doc. dr Svitlana INDYKA; prof. dr hab. Tomasz JUREK; dr hab. prof. UR Paweł KRÓL; dr hab. prof. AWF Adam MASZCZYK; dr hab. prof. AWF Jolanta MOGIŁA-LISOWSKA; prof. dr hab. Leonard NOWAK; doc. dr Vasyl PANTIK; dr hab. prof. UwB Artur PASKO; dr hab. prof. UMCS Dariusz SŁAPEK; dr hab. prof. US Renata URBAN; dr hab. prof. OSW Jerzy URNIAŻ; prof. dr hab. Marek WAIC; dr hab. prof. UAM Ryszard WRYK; prof. dr hab. Stanisław ZABORNIAK Nadesłane do redakcji artykuły są oceniane anonimowo przez dwóch Recenzentów UNIWERSYTET HUMANISTYCZNO-PRZYRODNICZY IM. -

Cultural Vs. Economic Legacies of Empires: Evidence from the Partition of Poland I

Motivation and Background Contributions Discussion and Conclusion Cultural vs. Economic Legacies of Empires: Evidence from the Partition of Poland I. Grosfeld and E. Zhuravakaya Luke Zinnen, Presenter EC 765, Spring 2018 Luke Zinnen, Presenter Cultural vs. Economic Legacies of Empires Motivation and Background Contributions Discussion and Conclusion Outline 1 Motivation and Background 2 Contributions Empirical Strategy Results 3 Discussion and Conclusion Luke Zinnen, Presenter Cultural vs. Economic Legacies of Empires Motivation and Background Contributions Discussion and Conclusion Economic and Political Persistence of Historical Events Major and growing literature on connection between historical events and current political and economic outcomes Slavery Imperialism Unclear what carries through intervening time Economic factors Cultural Institutional Likewise, mechanisms important: which are overriden by later shocks, policy? Luke Zinnen, Presenter Cultural vs. Economic Legacies of Empires Motivation and Background Contributions Discussion and Conclusion Goals and Outcomes of the Paper Use 1815 - 1918 partition of Poland between Russia, Prussia/Germany, and Austria/Austria-Hungary as clean case to examine persistent and attenuated factors Homogenous before and after partition Partition arbitrary and with sharp borders Large dierences between absorbing empires Employ spacial regression discontinuity analysis on localities near empire borders during partition Find little persistent dierence in most economic outcomes (exception: railroad infrastructure), more for religiosity and democratic capital Latter have observable eect on liberal/religious conservative voting patterns Luke Zinnen, Presenter Cultural vs. Economic Legacies of Empires Motivation and Background Contributions Discussion and Conclusion Related Literature Persistence of culture and institutions, and their long-term eects on development Colonial rule and post-independence institutions: (Acemoglu et al.