Interview with Sean Ellis Re: Graphic Adventure Creator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pcbs : 465 in 1 Babystar PCB

PCBs : 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB 465 Games in 1 BabyStar PCB Rating: Not Rated Yet Price: Sales price: $274.95 Discount: Ask a question about this product Description 465 in 1 BabyStar PCB ***ATX Power Supply with P4 connector required for operation*** JAMMA ready arcade system containing 465 vertical ready to play games. Choose from classics like Ms. Pac man, Donkey Kong, and Frogger to great shooters like 19XX, Strikers 1945 II, and Varth! The game selection menu is easy to understand and navigate. To select a game, scroll through the list and press your button to select. At anytime during the active game aplayer can return back to main game selection menu by holding in the start button for 3 seconds. This sytem runs on a stable flash drive. No hard drive to ever fail! Supports Vertically mounted monitors only. Universal JAMMA Connector. User Friendly Game Selection Screen. P4 Motherboard using genuine Intel Processor and Card Flash memory creates a faster/more stable system! User Adjustable Game Options (Game Dip Switch Settings; Number of Lives, Difficulty, etc). Supports 1-4 Player Games (players 3 & 4 via linking - kit included). Supports two-channel audio (Stereo Sound). Supports CGA Standard Arcade Monitor (15kHz). Supports Upright Cabinets (will not flip screen for cocktails). Enable One Game (for a dedicated machine if desired) or All Games. Enable/Disable Individual Game Categories From Showing. Delete/Undelete Each Game. Set Coin/Credit Ratio of All Games with One Setting. Supports a Coin Counter. System Specifications: JAMMA Controller/Interface PCB. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Edição De Natal !

Ano II - Número 5 A revista eletrônica do entusiasta de videogames e microcomputadores clássicos Visitamos a Cinótica! EDIÇÃO DE NATAL ! Entrevistas Internacionais: Ralph Baer Howard S. Warshaw Reviews Especiais: . Prince of Persia . Em Busca dos Tesouros JOGOS 80 1 INDICE C.P.U. EXPEDIENTE Beta - O Retorno ...................................... 04 Jogos 80 é uma publicação da Dickens Editora Virtual. Editor CURIOSIDADES Marcus Vinicius Garrett Chiado Konami´s Synthesizer .............................. 24 Visita à Cinótica ...................................... 22 Co-Editor Eduardo Antônio Raga Luccas Redatores desta Edição EDITORIAL .......................................... 03 Carlos Bragatto Eduardo Antônio Raga Luccas Ericson Benjamin Jorge Braga da Silva JOYSTICK Marcelo Tini E.T. Phone Home! .................................... 17 Marcus Vinicius Garrett Chiado Em Busca dos Tesouros ........................... 09 Murilo Saraiva de Queiroz Fiendish Freddy’s Big Top O’ Fun ............ 15 Revisão M.A.S.H. .................................................. 14 Eduardo Antônio Raga Luccas Prince of Persia ........................................ 11 Marcus Vinicius Garrett Chiado Logotipo Rick Zavala PERSONALIDADES Howard Scott Warshaw .......................... 19 Projeto gráfico e diagramação Ralph Baer .............................................. 06 LuccasCorp. Computer Division Agradecimentos André Saracene Forte TELEX Carlos Bragatto Fernando Salvio Especial: Depoimentos de Natal ............ 25 Howard Scott Warshaw Ralph Baer -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

Tecnologias Da Informação E Comunicação

Referências: Guia da Exposição "Memórias das Tecnologias e dos Sistemas de Informação" www.memtsi.dsi.uminho.pt Colecção: memTSI, DSI e Alfamicro http://piano.dsi.uminho.pt/museuv Departamento de Sistemas de Informação da UM www.memtsi.dsi.uminho.pt http://piano.dsi.uminho.pt/museuv || Sinclair ZX81 || Sinclair ZX SPECTRUM || TIMEX 1500 || TIMEX TC 2068 Máquina lançada em 1981, Lançado em 1982, foi um O Timex 1500 foi criado em O Timex TC 2068 foi TECNOLOGIAS com 1K de memória (max dos maiores sucessos Julho de 1983 e era desenvolvido no final de 16K), sem som e sem cor. comerciais no mercado dos basicamente um sinclair 1983 com um processador “home computers”, Z81 com 16KB de RAM Z80A a 3,5 Mhz. DA INFORMAÇÃO desenhado e comercializado incorporada com Dispunha de 48KB de por uma empresa do Reino possibilidade de expansão memória RAM e 16KB de E COMUNICAÇÃO Unido (Sinclair) por poucas até 64KB. memória ROM. TIC dezenas de contos (o preço Tinha um processador Dispunha de conectores de lançamento foi £129.95 ZILOG Z80A que funcionava para monitor, joystick, no Reino Unido). a uma velocidade de 3,5Mhz. leitor/gravador de casetes, Descendente directo do A imagem em ecrã era a 2 porta de expansão e ZX81, incorporou cor e som. cores com uma resolução televisão, usando um sinal Configuração completa com de 64x44. PAL. impressora térmica Sinclair Em modo de texto permitia Tinha uma resolução de 2040 e um gravador áudio 32 colunas e 24 linhas. 256x192 píxeis e permitia (periférico de arquivo) e Não dispunha de som. -

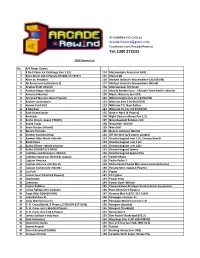

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

Melbourne House at Our Office Books and Software That Melbourne House Has Nearest to You: Published for a Wide Range of Microcomputers

mELBDLIAnE HO LISE PAESEnTS camPLITEA BDDHSB SDFTWAAE Me·lbourne House is an international software publishing company. If you have any difficulties obtaining some Dear Computer User: of our products, please contact I am very pleased to be able to let you know of the Melbourne House at our office books and software that Melbourne House has nearest to you: published for a wide range of microcomputers. United States of America Our aim is to present the best possible books and Melbourne House Software Inc., software for most home computers. Our books 347 Reedwood Drive, present information that is suitable for the beginner Nashville TN 37217 computer user right through to the experienced United Kingdom computer programmer or hobbyist. Melbourne House (Publishers) Ltd., Our software aims to bring out the most possible Glebe Cottage, Glebe House, from each computer. Each program has been written to be a state-of-the-art work. The result has been Station Road, Cheddington, software that has been internationally acclaimed. Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, LU77NA. I would like to hear from you if you have any comments or suggestions about our books and Australia & New Zealand software, or what you would like to see us publish. Melbourne House (Australia) Pty. Ltd., Suite 4, 75 Palmerston Crescent, If you have written something for your computer-a program, an article, or a book-then please send it to South Melbourne, Victoria 3205. us. We will give you a prompt reply as to whether it is a work that we could publish. I trust that you will enjoy our books and software. -

Aboard the Impulse Train: an Analysis of the Two- Channel Title Music Routine in Manic Miner Kenneth B

All aboard the impulse train: an analysis of the two- channel title music routine in Manic Miner Kenneth B. McAlpine This is the author's accepted manuscript. The final publication is available at Springer via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40869-015-0012-x All Aboard the Impulse Train: An analysis of the two-channel title music routine in Manic Miner Dr Kenneth B. McAlpine University of Abertay Dundee Abstract The ZX Spectrum launched in the UK in April 1982, and almost single- handedly kick-started the British computer games industry. Launched to compete with technologically-superior rivals from Acorn and Commodore, the Spectrum had price and popularity on its side and became a runaway success. One area, however, where the Spectrum betrayed its price-point was its sound hardware, providing just a single channel of 1-bit sound playback, and the first-generation of Spectrum titles did little to challenge the machine’s hardware. Programmers soon realised, however, that with clever machine coding, the Spectrum’s speaker could be encouraged to do more than it was ever designed to. This creativity, borne from constraint, represents a very real example of technology, or rather limited technology, as a driver for creativity, and, since the solutions were not without cost, they imparted a characteristic sound that, in turn, came to define the aesthetic of ZX Spectrum music. At the time, there was little interest in the formal study of either the technologies that support computer games or the social and cultural phenomena that surround them. This retrospective study aims to address that by deconstructing and analysing a key turning point in the musical life of the ZX Spectrum. -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

ED 278 545 AUTHOR Conference on Science and Technology

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 278 545 SE 047 709 AUTHOR Thulstrup, Erik W., Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the NordicConference on Science and Technology Education: The Challengeof the Future (Karlslunde Strand, Denmark, May8-12, 1985). INSTITUTION Royal Danish School of EducationalStudies, Copenhagen (Denmark). SPONS AGENCY Nordic Culture Fund, Copenhagen(Denmark).; United Nations Educational, Scientific,and Cultural Organization, Paris (France). REPORT NO ISBN-87-88289-50-8 PUB DATE 8 May 85 NOTE 410p.; Document contains small print;drawings may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Collected Works- Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/12C17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Biological Sciences; ComputerUses in Education; Educational Trends; Energy Education;*Environmental Education; *International EducationalExchange; International Programs; MathematicsEducation; Models; *Physical Sciences; Scienceand Society; *Science Curriculum; ScienceEducation; *Science Instruction; Student Attitudes IDENTIFIERS *Nordic Countries ABSTRACT The Nordic Conference of 1985was convened for the purpose of fostering cooperation between scienceand technology educators within different fieldsand at different levels, with approximately 40 science and technologyeducators from Finland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, India,the United States, and Yugoslavia participating. This report contains27 contributed papers fromthe conference. Some of the topics addressedinclude: (1) teaching with computers; (2) physics instruction; (3)theory of mathematics education; (4) UNESCO's activitiesin science -

New Joysticks Available for Your Atari 2600

May Your Holiday Season Be a Classic One Classic Gamer Magazine Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 3 The Xonox List 27 Teach Your Children Well 28 Games of Blame 29 Mit’s Revenge 31 The Odyssey Challenger Series 34 Interview With Bob Rosha 38 Atari Arcade Hits Review 41 Jaguar: Straight From the Cat’s 43 Mouth 6 Homebrew Review 44 24 Dear Santa 46 CGM Online Reset 5 22 So, what’s Happening with CGM Newswire 6 our website? Upcoming Releases 8 In the coming months we’ll Book Review: The First Quarter 9 be expanding our web pres- Classic Ad: “Fonz” from 1976 10 ence with more articles, games and classic gaming merchan- Lost Arcade Classic: Guzzler 11 dise. Right now we’re even The Games We Love to Hate 12 shilling Classic Gamer Maga- zine merchandise such as The X-Games 14 t-shirts and coffee mugs. Are These Games Unplayable? 16 So be sure to check online with us for all the latest and My Favorite Hedgehog 18 greatest in classic gaming news Ode to Arcade Art 20 and fun. Roland’s Rat Race for the C-64 22 www.classicgamer.com Survival Island 24 Head ‘em Off at the Past 48 Classic Ad: “K.C. Munchkin” 1982 49 My .025 50 Make it So, Mr. Borf! Dragon’s Lair 52 and Space Ace DVD Review How I Tapped Out on Tapper 54 Classifieds 55 Poetry Contest Winners 55 CVG 101: What I Learned Over 56 Summer Vacation Atari’s Misplays and Bogey’s 58 46 Deep Thaw 62 38 Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 4 “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to Issue 5 repeat it” - George Santayana December 2000 Editor-in-Chief “Unfortunately, those of us who do remember the past are Chris Cavanaugh condemned to repeat it with them." - unaccredited [email protected] Managing Editor -Box, Dreamcast, Play- and the X-Box? Well, much to Sarah Thomas [email protected] Station, PlayStation 2, the chagrin of Microsoft bashers Gamecube, Nintendo 64, everywhere, there is one rule of Contributing Writers Indrema, Nuon, Game business that should never be X Mark Androvich Boy Advance, and the home forgotten: Never bet against Bill. -

More Real Applications for the ZX 81 and ZX Spectrum

More Real Applications for the ZX 81 and ZX Spectrum Macmillan Computing Books Assembly Language Programming for the BBC Microcomputer Ian Birnbaum Advanced Programming for the 16K ZX81 Mike Costello Microprocessors and Microcomputers - their use and programming Eric Huggins The Alien, Numbereater, and Other Programs for Personal Computers with notes on how they were written John Race Beginning BASIC Peter Gosling Continuing BASIC Peter Gosling Program Your Microcomputer in BASIC Peter Gosling Practical BASIC Programming Peter Gosling The Sinclair ZX81 - Programming for Real Applications Randle Hurley More Real Applications for the Spectrum and ZX81 Randle Hurley Assembly Language Assembled - for the Sinclair ZX81 Tony Woods Digital Techniques Noel Morris Microprocessor and Microcomputer Technology Noel Morris Understanding Microprocessors B. S. Walker Codes for Computers and Microprocessors P. Gosling and Q. Laarhoven Z80 Assembly Language Programming for Students Roger Hutty More Real Applications for the ZX81 and ZX Spectrum Randle Hurley M © Randle Hurley 1982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form of by any means, without permission. Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Company and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-0-333-34543-6 ISBN 978-1-349-06604-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-06604-9 The paperback edition of this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.