John Benjamins Publishing Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U R U G U a Y

Telephone: 598 26040329 U R U G U A Y ext. 1260, 1463 Dirección Nacional de Aviación Civil e Infraestructura Aeronáutica AMDT Telefax: 598 26040067 Servicio de Información Aeronáutica NR 56 AFTN: SUMUYNYX Aeropuerto Intl de Carrasco “Gral. Cesáreo L. Berisso” 01 DEC 2018 e-mail: [email protected] 14000 Canelones The entries with an indicator (!) at the margin indicates changes in the paragraph EFFECTIVE DATE: 01 DEC 2018 - 03:01 UTC THIS AMDT MUST NOT BE INSERTED INTO THE AIP BEFORE THE EFFECTIVE DATE. HOWEVER, IT IS SUGGESTED TO STUDY ITS CONTENT BEFORE THAT DATE. 1. INSERT AND/OR DESTROY THE FOLLOWING PAGES: DESTROY INSERT GEN GEN 0.4-1 ........................................ 11 OCT 2018 0.4-1............................... 01 DEC 2018 0.4-2 ........................................ 11 OCT 2018 0.4-2............................... 01 DEC 2018 0.4-3 ........................................ 11 OCT 2018 0.4-3............................... 01 DEC 2018 0.4-4 ........................................ 01 APR 2018 0.4-4............................... 01 DEC 2018 0.4-5 ........................................ 01 AUG 2018 0.4-5............................... 01 DEC 2018 0.4-6 ........................................ 01 DEC 2017 1.5-1....... ................................. 02 JAN 2017 1.5-1............................... 01 DEC 2018 1.6-1 ........................................ 02 JAN 2017 1.6-1............................... 01 DEC 2018 1.6-2 ........................................ 01 APR 2002 1.6-3 ........................................ 01 APR 2002 1.6-4 ........................................ 01 APR 2014 1.6-5 ........................................ 01 DEC 2010 1.6-6 ........................................ 01 DEC 2010 1.6-7 ........................................ 01 APR 2014 1.6-8 ........................................ 01 APR 2014 1.6-9 ........................................ 01 APR 2014 1.6-10 ...................................... 02 JAN 2017 1.6-11 ...................................... 01 APR 2014 1.6-12 ..................................... -

Vulnerability of Family Livestock Farming on the Livramento-Rivera Border of Brazil and Uruguay: Comparative Analysis

Vulnerability of family livestock farming on the Livramento-Rivera border of Brazil and Uruguay: Comparative analysis Paulo D. Waquil1* Marcio Z. Neske1 Claudio M. Ribeiro2,3 Fabio E. Schlick2 Tanice Andreatta4 Cleiton Perleberg4 Marcos F.S. Borba5 Jose P. Trindade5 Rafael Carriquiry6,7 Italo Malaquin7 Alejandro Saravia7,8 Mario Gonzales9 Livio S.D. Claudino10 Keywords Summary Cattle, family farm, risk factor, Social, ecological, and economic sciences have all shown interest in studying ET FILIÈRES SYSTÈMES D’ÉLEVAGE Brazil, Uruguay the social group called family livestock farmers. The main characteristic of this ■ group, which is present in the Pampa biome in Southern Brazil and Uruguay, Accepted: 21 December 2014; Published: is beef cattle production based on family work on small lands, expressing an 25 March 2016 autonomous way of life which is, however, highly dependent on strong relations with the physical environment and marked by risk aversion. In this study we made a comparative analysis of vulnerability factors of family livestock farm- ing in Brazil and Uruguay. We also compared these social actors’ perceptions of risks, and the strategies built to mitigate threats. A survey was thus carried out and included 16 family livestock farmers’ interviews, eight in each country, near the cities of Santana do Livramento (Brazil) and Rivera (Uruguay). Although these cities are next to each other on each side of the border and thus present environmental similarities, we chose them because family farming was not sub- jected to the same political and economic conditions which might (or might not) have influenced farmers’ perceptions and reactions. Results showed that live- stock farmers were mainly affected by vulnerabilities arising from external ele- ments such as the climate (e.g. -

Livestock Farming Embedded in Local Development: Functional Perspective En Recherche Agronomique Pour Le Développement to Alleviate Vulnerability of Rural Communities

Contents Sommaire LiFLoD Livestock Farming & Local Development Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina 31 March – 1 April 2011 www.liflod.org Workshop held during the 9th International Rangeland Congress ISSN 1951-6711 Publication du Centre de coopération internationale 51-53 Livestock farming embedded in local development: Functional perspective en recherche agronomique pour le développement to alleviate vulnerability of rural communities. Tourrand J.-F., Waquil P.D., Sraïri M.T., http://revues.cirad.fr/index.php/REMVT http://www.cirad.fr/ Hubert B. (in English) Directeur de la publication / Publication Director: LIVESTOCK FARMING SYSTEMS AND VALUE CHAINS Michel Eddi, PDG / President & CEO SYSTÈMES D’ÉLEVAGE ET FILIÈRES Rédacteurs en chef / Editors-in-Chief: Gilles Balança, Denis Bastianelli, Frédéric Stachurski 55-59 Vulnerability of family livestock farming on the Livramento-Rivera border of Brazil and Uruguay: Comparative analysis. Vulnérabilité des éleveurs familiaux à la Rédacteurs associés / Associate Editors: Guillaume Duteurtre, Bernard Faye, Flavie Goutard, frontière entre Livramento et Rivera au Brésil et en Uruguay : analyse comparative. Waquil Vincent Porphyre P.D., Neske M.Z., Ribeiro C.M., Schlick F.E., Andreatta T., Perleberg C., Borba M.F.S., Trindade J.P., Carriquiry R., Malaquin I., Saravia A., Gonzales M., Claudino L.S.D. (in English) Coordinatrice d’édition / Publishing Coordinator: Marie-Cécile Maraval 61-67 Opportunism and persistence in milk production in the Brazilian Traductrices/Translators: Amazonia. Opportunisme et persistance dans la production de lait en Amazonie Marie-Cécile Maraval (anglais), brésilienne. De Carvalho S.A., Poccard-Chapuis R., Tourrand J.-F. (in English) Suzanne Osorio-da Cruz (espagnol) Webmestre/Webmaster: Christian Sahut 69-74 Rangeland management in the Qilian mountains, Tibetan plateau, China. -

Check List 4(4): 434–438, 2008. ISSN: 1809-127X

Check List 4(4): 434–438, 2008. ISSN: 1809-127X NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Reptilia, Gekkonidae, Hemidactylus mabouia, Tarentola mauritanica: Distribution extension and anthropogenic dispersal Diego Baldo 1 Claudio Borteiro 2 Francisco Brusquetti 3 José Eduardo García 4 Carlos Prigioni 5 1 Universidad Nacional de Misiones, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas Químicas y Naturales. Félix de Azara 1552, (3300). Posadas, Misiones, Argentina. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Río de Janeiro 4058, 12800, Montevideo, Uruguay. 3 Instituto de Investigación Biológica del Paraguay (IIBP). Del Escudo 1607. 1429. Asunción, Paraguay. 4Dirección Nacional de Aduanas, La Coronilla, Rocha, Uruguay. Leopoldo Fernández s/n, La Coronilla, Rocha, Uruguay 5Museo Nacional de Historia Natural y Antropología. 25 de Mayo 582, Montevideo, Uruguay. The gekkonid genera Hemidactylus and Tarentola also found in an urban area (Achaval and Gudynas are composed by small sized lizards, noticeably 1983). able to perform long distance natural and anthropogenic dispersal, followed by colonization In this work we present new records of both of new areas (Kluge 1969, Vanzolini 1978, species in Uruguay, some of them associated to Carranza et al. 2000, Vences et al. 2004). Newly accidental anthropogenic dispersal, new records of introduced gecko species, at least of the genus H. mabouia in Argentina, and the first record of Hemidactylus, were reported as capable of the H. mabouia for Paraguay. Vouchers are displacing native ones (Hanley et al. 1998, Dame deposited at Colección Diego Baldo, housed at and Petren 2006, Rivas Fuenmayor et al. 2005). Museo de La Plata, Argentina (MLP DB), Colección Zoológica de la Facultad de Ciencias Interestingly, human related translocations aided Exactas y Naturales, Asunción, Paraguay some of these invasive lizards to have currently an (CZCEN), Museo Nacional de Historia Natural almost cosmopolitan distribution in tropical and de Montevideo (MNHN, currently Museo temperate regions (Vences et al. -

European Commission Dg(Sanco

EUROPEAN COMMISSION HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL Directorate F - Food and Veterinary Office DG(SANCO)/3399/2001 – MR FINAL FINAL REPORT OF A MISSION CARRIED OUT IN URUGUAY FROM 17/09/2001 TO 21/09/2001 IN ORDER TO EVALUATE THE INSPECTION PROCEDURES FOR CITRUS FRUIT ORIGINATING IN URUGUAY AND EXPORTED TO THE EUROPEAN UNION Please note that factual errors in the draft report have been corrected in bold, italic, type. Clarifications provided by the Uruguayan authorities are given as footnotes, in bold, italic, type, to the relevant part of the report. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 1 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE MISSION............................................................................. 1 3. LEGAL BASIS FOR THE MISSION ........................................................................ 1 4. BACKGROUND......................................................................................................... 2 4.1. Background to present mission ......................................................................... 2 4.2. Production and trade information...................................................................... 2 4.3. Health information............................................................................................ 3 5. MAIN FINDINGS ...................................................................................................... 3 5.1. Competent authority......................................................................................... -

URUGUAY by Alfredo C

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF URUGUAY By Alfredo C. Gurmendi 1 Uruguay is a small, open-market economy that allows Provisions of the 1972 Mining Code are as follows: a private ownership. It is largely agrarian, with a liberal prospecting permit is issued for up to 1,000 square foreign investment policy, political stability, a progressive kilometers (km2) and a 2-year term; an exploration permit is Government, outstanding regional and international relations, for up to 10 km2 and a 2-year term; and a mining concession and tremendous hydropower potential. The production of is for a maximum of 5 km2 and up to a 30-year term. Decree minerals is evolving from small-scale to more capital- No. 516/990 of November 1990 authorized the intensive mining operations. The mining industry has Administración Nacional de Combustibles, Alcohol y attracted domestic and foreign investors, particularly from Portland (ANCAP) to call for tenders from companies Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Italy, Japan, and the United interested in offshore drilling. States, to produce granite, gold, and semiprecious stones. Uruguay's mining and quarrying were for gold and The gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 2% to $15 construction minerals, such as clays, dimension stone, billion,2 while the rate of inflation was 44% by yearend, dolomite, granite, gypsum, limestone, marble, quartz, and representing a decrease from that of 1993, when it was 53%. sand and gravel. The Mahoma gold project, 60 kilometers The foreign debt increased by $300 million to $4.2 billion, (km) northwest of San José, came on-stream at an initial unemployment reached 9.6%, and the country's international production of 1,250 kilograms per year (kg/a). -

1. General Information on the Scope of the IDB Invest Environmental and Social Review

I) Fideicomiso Financiero Conaprole, y II) Conaprole - IDBInvest Corporativo 1. General information on the scope of the IDB Invest Environmental and Social Review Conaprole is an Uruguayan dairy company that processes 1,650 million liters of milk per year and produces more than 300 products, meeting domestic market needs and exporting to more than 50 countries. The company is Latin America’s leading dairy exporter and has commercial offices in the United States, China, and Brazil. It has the following eight industrial plants: Montevideo Industrial Complex (CIM – Plant 21), Villa Rodríguez Industrial Complex (CIVR – Plant 8), Florida Industrial Complex (CIF – Plant 7), San Ramón Industrial Complex (CISF – Plant 9), San Carlos Plant (Plant 10), Rincón del Pino Plant (Plant 11), Mercedes Plant (Plant 16), and Rivera Plant (Plant 14). Those plants produce liquid pasteurized milk (fresh and extended shelf-life), flavored milks, cheeses, dried products (powdered milk and whey), butter, heavy cream, dulce de leche, desserts, yogurts, ice creams, and juices. There are products (frozen foods and tomato pulp) that are made by third parties according to Conaprole guidelines. The company is governed by a Board (5 members), the Producers’ Assembly (29 members), a Fiscal Commission (3 members), and nine committees (Audit and Surveillance Committee, Human Resources Committee, Water Committee, Engineering Committee, Energy Committee, Management Committee, External Market Committee, Domestic Market Committee, and Sustainability Committee). Between April 2 and April 5, 2019, responsible staff from the IDB Invest Environmental, Social, and Governance Department (SEG) conducted the due environmental and social due diligence process for this transaction, holding meetings with responsible Conaprole staff at the plants in Montevideo, Villa Rodríguez, Florida, and San Ramón. -

Sgs Qualifor Informe De Certificación De Manejo

SGS QUALIFOR Doc. Number: AD 36A-12 (Associated Documents) Doc. Version date: 21 Sept. 2010 Page: 1 of 120 Approved by: Gerrit Marais INFORME DE CERTIFICACIÓN DE MANEJO FORESTA FOREST MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION REPORT SECCIÓN A: RESUMEN PÚBLICO / SECTION A: PUBLIC SUMMARY Número de proyecto: 7021-UY Project No: Cliente: Forestal Oriental S.A. Client: Página web: www.forestaloriental.com.uy Web Page: Domicilio: 18 de julio 818. Paysandú Address: País: Uruguay Country: Tipo de Manejo Forestal y Cadena de Número de certificado: certificado: Custodia SGS-FM/CoC-000606 Certificate No: Certificate Type: Forest Management and Chain of Custody Fecha de Fecha de emisión: 05 Jan 2011 vencimiento: 04 Jan 2016 Date of Issue: Date of expiry: SGS Estándares de Manejo Forestal (AD33) adaptado para Uruguay, versión 04 Estándar de de 14 de julio de 2010 evaluación: Evaluation Standard: SGS Forest Management Standard (AD33) adapted for Uruguay, version 04 of 14 July 2010 Zona Forestal: Templado Forest Zone: Temperate Área Total Certificada: 209,483ha Total Certified Area: Alcance: Manejo forestal de las plantaciones en los Departamentos de Paysandú, Río Negro, Tacuarembó, Cerro Largo, Durazno y Soriano de Uruguay, para la Scope: producción de madera de coníferas y latifoliadas. Forest Management of plantations in the Paysandú, Rio Negro, Tacuarembó, Cerro Largo, Durazno and Soriano regions of Uruguay for the production of softwood and hardwood timber. Ubicación de las UMF Departamentos de Paysandú, Río Negro, Tacuarembó, Cerro Largo , Soriano y incluida en el ámbito de Durazno alcance: SGS services are rendered in accordance with the applicable SGS General Conditions of Service accessible at http://www.sgs.com/terms_and_conditions.htm SGS South Africa (Qualifor Programme) 58 Melville Road, Booysens - PO Box 82582, Southdale 2185 -SouthSouth AAfricafrica Systems and Services Certification Division Contact Programme Director at t. -

List of Sources

List of Sources General Bolivia La Paz, Altmir, 0., The Extent of Poverty in Latin America. Bird Working Anuario Geografico. Estadistico de La Republica de Bolivia. Paper 522, Washington, 1982. 1988. Blackmore, H.&: Smith, C.T. Latin America. London, Methuen, 1983. Area Handbook Series: Bolivia - A Country Study. The American Bulterworth, D., Latin American Urbanization. Cambridge, Cambridge University, Washington D.C. University Press, 1981. Dummerley, J., Rebellion in the Veins, Political Struggle in Bolivia Butland, G.J., Latin America. John Witey &: Son. N.Y., 1966. I95I-I982. Verso, 1984. Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook I990. Washington Fifer, J.V., Bolivia: Land, Location and Politics Since I825. California D.C. University Press, 1972. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., I987 Britannica World Data. Chicago, Chile 1987. Anuario Estadistico. lnstituto Nacional de Estadistica. Santiago, 1988. Economic Relations between Europe and Gleich, A., The Political and Area Handbook Series: Chile - A Country Study. The American 1983. Latin America. I.E.I. Hamburg, Universtiy. Washington D.C. Oxford, 1990. Heinemann Educational, Geographical Digest I990-9I. Militar, Atlas Geografico de Chile, para Ia Agostini I990. lnstituto Geogratico lnstituto Geografico de Agostini, Calendario At/ante De Educacion. Santiago, 1985. Novara, 1989. T.X., &: Alvarado, E.Z., Geografia de Chile, Editoria 1969. Olivares, Jones, Preston E., Latin America. 3rd Ed. London, Cassel, Universitaria, 1984. Lambert, D.C., Ameriques Latines. Declins et Decollages, Ed. Economica, Paris, 1984. Argentina Morris, A.S., Latin America Economic Development and Regional Area Handbook Series: Argentina - A Country Study. The American Differentiation. Totowa, N.J., Barnes and Noble, 1981. University, Washington D.C. Morris, A., South America. -

Uruguay Immigration Detention Data Profile

Uruguay Immigration Detention Data Profile Global Detention Project Profile Quick Facts Immigration detainees Not Available (2019) Detained minors (2017) Not Available International migrants 81,482 (2019) New asylum applications 12,222 (2019) NOTES ON USING THIS PROFILE • Sources for the data provided in this report are available online at: https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/americas/uruguay • "Observation Dates" indicate the timeframe statistical data correspond to or other data were last validated. More than one statistical entry for a year indicates contrasting reports. © Global Detention Project 2021 1/6 STATISTICS Detention, expulsion, and incarceration statistics Observation Date Observation Date Total number of Not Available 2019 Total number of Not Available 2017 immigration detainees detained minors by year 10,228 2016 2.8 2015 9,829 2013 2.7 2006 8,700 2010 7,186 2007 Criminal prison Percentage of foreign 6,888 2004 population prisoners 5,107 2001 3,927 1998 3,192 1995 3,157 1992 297 2016 289 2013 257 2010 215 2007 Prison population rate (per 100,000 of national 207 2004 population) 154 2001 119 1998 99 1995 100 1992 Demographics and immigration-related statistics Observation Date Observation Date 3,500,000 2020 81,482 2019 Population International migrants 3,432,000 2015 71,800 2015 2.4 2019 498 2019 2.1 2015 391 2018 International migrants 344 2017 as a percentage of the Refugees population 274 2016 289 2015 272 2014 0.09 2016 12,222 2019 Ratio of refugees per Total number of new 0.08 2015 378 2016 1000 inhabitants -

Is Grazing Land, Where Extensive Grazing of Natural Grass Is Conducted

State of Baselines ・ Grazing land in Uruguay Some 80 % of Uruguay’s land (about 14 million hectares) is grazing land, where extensive grazing of natural grass is conducted. In some grazing land with high productivity (mainly located in western, southwestern and southern areas), intensive grazing using improved grass is conducted. Such grazing lands were widely covered with forests in past days; however, the forests have been eliminated due to long-lasting cutting by settlers. The land which becomes grazing land is not easily recovered as forests even if the land is left to take its own course. One of the reasons for this is that conditions are good for forming a grassland, such as the climate in which there is not so much precipitation (the average annual precipitation is 1,000 mm) , while a situation in which the amount of evapotranspiration and precipitation are almost the same lasts for several months. This kind of climate creates the conditions conducive to the forming of grassland. For example, the climate prevents rain from penetrating into the deeper part of soil. As a result, only surface soil holds adequate humidity. Another reason is that the conditions where grazing land is burned intentionally every year, and old grass is replaced by new grass are maintained in many cases. From the above, we can consider that there is a high possibility that the existing grazing lands will be maintained in the same conditions. Therefore, the present state can be considered the baseline.The species of grasses that grow there are Eryngeon, Bachris, Cenecio, Paspalum qusdrifarium, P. -

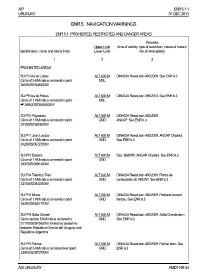

Enr 5. Navigation Warnings

AIP ENR 5.1-1 URUGUAY 01 DEC 2013 ENR 5. NAVIGATION WARNINGS ENR 5.1 PROHIBITED, RESTRICTED AND DANGER AREAS Remarks Upper Limit (time of activity, type of restriction, nature of hazard, Identification, name and lateral limits Lower Limit risk of interception) 1 2 3 PROHIBITED AREAS SU P2 Isla de Lobos ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 450/2009. See ENR 6.3 Circle of 5 KM radius centered in point MSL 350200S/0545300W SU P9 Isla de Flores ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 396/2013. See ENR 6.3 Circle of 1 KM radius centered in point MSL !345633S/05555535W SU P10 Paysandú ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 450/2009. Circle of 1 KM radius centered in point GND ANCAP. See ENR 6.3 321500S/0580500W SU P11 Juan Lacaze ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 450/2009. ANCAP Oil plant. Circle of 1 KM radius centered in point GND See ENR 6.3 342500S/0572700W SU P12 Dolores ALT 600 M Dec. 568/970. ANCAP Oil plant. See ENR 6.3 Circle of 1 KM radius centered in point GND 333100S/0581400W SU P14 Treinta y Tres ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 450/2009. Planta de Circle of 1 KM radius centered in point GND combustible de ANCAP. See ENR 6.3 331400S/0542200W SU P15 Minas ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 450/2009. Portland cement Circle of 1 KM radius centered in point GND factory. See ENR 6.3 342400S/0551700W SU P18 Salto Grande ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 450/2009. Salto Grande dam. Circle section 5 KM radius centered in GND See ENR 6.3 311700S/0575600W, limited by borderline between República Oriental del Uruguay and República Argentina SU P19 Palmar ALT 600 M DINACIA Resolution 450/2009.