Island Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AI Hubs: Europe and CANZUK

April 2021 AI Hubs Europe and CANZUK CSET Data Brief AUTHORS Max Langenkamp Melissa Flagg Executive Summary With the increasing importance of artificial intelligence to national and economic security, and the growing competition for AI talent globally, it is essential for U.S. policymakers to understand the landscape of AI talent and investment. This knowledge is critical as U.S. leadership develops new alliances and works to curb the growing influence of China. As an initial effort, an earlier CSET report, “AI Hubs in the United States,” examined the domestic AI ecosystem by mapping where U.S. AI talent is produced, where it is concentrated, and where AI private equity funding goes. That work showed that AI talent and investment was concentrated in specific, well-defined geographic centers referred to as “AI Hubs.” Given the global characteristics of the AI ecosystem and the importance of international talent flows, it is equally important to consider the AI landscape outside of the United States. To provide insights to U.S. policymakers on the larger aspects of international AI talent, this paper builds on our earlier U.S. domestic research by exploring the centers of AI talent and investment in countries and regions that are key U.S. partners: Europe and CANZUK (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom). As before, we examine patterns of investment into privately held AI companies, the geography of top AI research universities, and the location of self-reported AI workers. The key findings: • Traditional treaty partners, including France, Germany, and CANZUK countries, contain both a high number of the top AI research universities and a high number of workers with self-reported AI skills. -

The Socio-Economic Impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in Times of Corona: the Case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand Kohnert, Dirk

www.ssoar.info The socio-economic impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in times of Corona: The case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand Kohnert, Dirk Preprint / Preprint Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kohnert, D. (2021). The socio-economic impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in times of Corona: The case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand.. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-73206-3 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-SA Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-SA Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Weitergebe unter gleichen (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike). For more Information Bedingungen) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den see: CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de The socio-economic impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in times of Corona : The case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand Dirk Kohnert 1 ‘Britannia as Miss Havisham’ 2 Source: The Guardian / Olusoga, 2017 Abstract: Although Britain has been one of the hardest hit among the EU member states by the corona pandemic, Boris Johnson left the EU at the end of 2020. Brexit supporters endorsed the idea of CANZUK, i.e. a union between the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The CANZUK was embedded in a vision of the revival of the olden days of Great Britain and its role in the ‘Anglosphere’, dating back to World War II and 19th-century British settler colonialism. -

Geopolitics, Education, and Empire: the Political Life of Sir Halford Mackinder, 1895-1925

Geopolitics, Education, and Empire: The Political Life of Sir Halford Mackinder, 1895-1925 Simone Pelizza Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, School of History Submitted March 2013 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2013 The University of Leeds and Simone Pelizza i Acknowledgements During the last three years I have received the kind assistance of many people, who made the writing of this thesis much more enjoyable than previously believed. First of all, I would like to thank my former supervisors at the University of Leeds, Professor Andrew Thompson and Dr Chris Prior, for their invaluable help in understanding the complex field of British imperial history and for their insightful advice on the early structure of the document. Then my deepest gratitude goes to my current supervisor, Professor Richard Whiting, who inherited me from Chris and Andrew two years ago, driving often my work toward profitable and unexplored directions. Of course, the final product is all my own, including possible flaws and shortcomings, but several of its parts really owe something to Richard’s brilliant suggestions and observations. Last but not least, I am very grateful to Pascal Venier, Vincent Hiribarren, and Chris Phillips, with whom I had frequent interesting exchanges on Mackinder’s geopolitical thought and its subtle influences over twentieth century international affairs. -

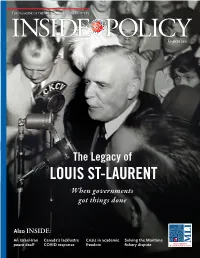

LOUIS ST-LAURENT When Governments Got Things Done

MARCH 2021 The Legacy of LOUIS ST-LAURENT When governments got things done Also INSIDE: An Israel-Iran Canada’s lacklustre Crisis in academic Solving the Maritime peace deal? COVID response freedom fishery dispute 1 PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee LeeBrianby Crowley, Crowley,the Lee Macdonald-Laurier Crowley,Managing Managing Managing Director, Director, Director [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames DeputyAnderson, Anderson, Managing Managing Managing Director, Editor, Editor, Editorial Inside Inside Policy and Policy Operations Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] David McDonough, Deputy Editor James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:Editor, writers: Inside Policy Contributing writers: ThomasThomas S. S.Axworthy Axworthy PastAndrewAndrew contributors Griffith Griffith BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. Axworthy Andrew Griffith Benjamin Perrin Mary-Jane BennettDonaldDonald Barry Barry Jeremy DepowStanleyStanley H. H. Hartt HarttMarcus Kolga MikeMike J.Priaro Berkshire Priaro Miller Massimo BergaminiDonald Barry Peter DeVries Stanley H. HarttAudrey Laporte Mike Priaro Jack Mintz Derek BurneyKenKen Coates Coates Brian Dijkema PaulPaul Kennedy KennedyBrad Lavigne ColinColin RobertsonRobert Robertson P. Murphy Ken Coates Paul Kennedy Colin Robertson Charles Burton Ujjal Dosanjh Ian Lee Dwight Newman BrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley Crowley AudreyAudrey Laporte Laporte RogerRoger Robinson Robinson Catherine -

REACHING the SUMMIT International Cooperation Takes Centre Stage in 2021 22715 Steinway ROSL JUN/AUG21 Kravitz.Qxp Layout 1 15/04/2021 11:03 Page 1

ISSUE 726 JUNE - AUGUST 2021 REACHING THE SUMMIT International cooperation takes centre stage in 2021 22715 Steinway ROSL JUN/AUG21 Kravitz.qxp_Layout 1 15/04/2021 11:03 Page 1 WELCOME KRAVITZ GRAND LIMITED EDITION The Royal Over-Seas League is dedicated A COLLABORATION WITH WORLD-RENOWNED MUSICIAN to championing international friendship and understanding through cultural and education “ Whilst travel has AND MODERN-DAY RENAISSANCE MAN LENNY KRAVITZ activities around the Commonwealth and beyond. A not-for-profit private members’ organisation, we’ve been bringing like-minded people been restricted, it's together since 1910. OVERSEAS EDITORIAL TEAM business as usual on Editor Mr Mark Brierley: [email protected]; +44 (0)20 7408 0214 Design the international stage” zed creative: www.zedcreative.co.uk Advertising [email protected] By the time this edition hits the doorstep, ROSL will have reopened its [email protected] doors. After what has been a long and difficult time for members and staff, ROYAL OVER-SEAS LEAGUE we’ll be into a wonderful spring and summer. We’re bursting into action Incorporated by Royal Charter Patron HM The Queen with the addition of two key new members of the team following our Vice-Patron HRH Princess Alexandra KG GCVO decision to take catering back in house – highly experienced Food and President The Rt Hon The Lord Geidt GCB GCVO OBE QSO PC Beverage Manager Serge Pradier, and Executive Chef Elliot Plimmer, who Chairman The Hon. Alexander Downer AC has Michelin starred experience. We will welcome -

The Anglosphere and Its Others: the ‘English‐Speaking Peoples’ in a Changing World Order

The Anglosphere and its Others: The ‘English‐speaking Peoples’ in a Changing World Order Venue: The British Academy, 10‐11 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AH 15 & 16 June Convenors: Professor Michael Kenny, University of Cambridge Dr Andrew Mycock, University of Huddersfield Dr Ben Wellings, Monash University Thursday, 15 June 2017 08.45 Registration and refreshments 09.15 Opening Address: Mr Matt Anderson, Deputy High Commissioner, Australian High Commission SESSION ONE: chaired by Professor Sarah Stockwell 9.30 Brexit, the Anglosphere and the emergence of ‘Global Britain’ Dr Andrew Mycock, University of Huddersfield 10.00 The Anglosphere and the End of Empire Professor Stuart Ward, University of Copenhagen 10.30 Discussion 10.50 Refreshments SESSION TWO: chaired by Dr Ben Wellings 11.20 Anglosphere: Legacy of Empire Dr Duncan Bell, University of Cambridge 11.50 Neoliberalism, the Anglosphere and Indigenous Peoples: the case of Aotearoa/New Zealand Associate Professor Katherine Smits, University of Auckland 12.20 Discussion 12.40 Lunch SESSION THREE: chaired by Professor Andrew Gamble 13.45 Policy transfer and international cooperation within the Anglosphere Dr Tim Legrand, Australian National University 14.15 The Anglosphere and CANZUK Mr James C Bennett, Independent/Anglosphere Institute 14.45 Discussion 15.05 Refreshments SESSION FOUR: chaired by Dr Andrew Mycock 15.35 The Anglosphere and Cricket Dr Dominic Malcolm, University of Loughborough 16.05 Language and Speech in the Anglosphere Professor Wendy Webster, University of Huddersfield -

Lord Rosebery and the Imperial Federation League, 1884-1893

Lord Rosebery and the Imperial Federation League, 1884-1893 BETWEEN 1884 and 1893 the Imperial Federation League flourished in Great Britain as the most important popular expression of the idea of closer imperial union between the mother country and her white self- governing colonies. Appearing as the result of an inaugural conference held at the Westminster Palace Hotel, London in July 1884,' the new League was pledged to 'secure by Federation the permanent unity of the Empire'2 and offered membership to any British subject who paid the annual registration fee of one shilling. As an avowedly propagandist organization, the League's plan of campaign included publications, lec- tures, meetings and the collection and dissemination of information and statistics about the empire, and in January 1886 the monthly journal Imperial Federation first appeared as a regular periodical monitoring League progress and events until the organization's abrupt collapse in December 1893. If the success of the foundation conference of July 1884 is to be measured in terms of the number of important public figures who attend- ed and who were willing to lend their names and influence to the move- ment for closer imperial union, then the meeting met with almost unqualified approval. When W.E. Forster addressed the opening con- ference as the chairman on 29 July 1884,3 the assembled company iry:lud- ed prominent politicians from both Liberal and Conservative parties in Great Britain, established political figures from the colonies, and a host of colonists and colonial expatriates who were animated by a great imperial vision which seemed to offer security and prosperity, both to the the mother country and to the colonies, in a world of increasing economic depression and foreign rivalry." Apart from the dedicated 1 Report of the Westminister Palace Hotel Conference, 29 July 1884, London, 1884, Rhodes House Library, Oxford. -

On the Use of the Term 'Commonwealth'

This article was downloaded by: [Commonwealth Secretariat] On: 30 March 2012, At: 04:07 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Commonwealth Political Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fccp18 On the use of the term ‘commonwealth’ S. R. Mehrotra a a School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London Available online: 25 Mar 2008 To cite this article: S. R. Mehrotra (1963): On the use of the term ‘commonwealth’, Journal of Commonwealth Political Studies, 2:1, 1-16 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14662046308446985 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. ON THE USE OF THE TERM 'COMMONWEALTH' BY S. -

Imperial Federation, Colonial Nationalism, and the Pacific Cable Telegraph, 1879-1902

“From One British Island to Another:” Imperial Federation, Colonial Nationalism, and the Pacific Cable Telegraph, 1879-1902 by Claire Oliver B.A., Portland State University, 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2018 © Claire Oliver, 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: “From One British Island to Another:” Imperial Federation, Colonial Nationalism, and the Pacific Cable Telegraph, 1879-1902 submitted by Claire Oliver in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Examining Committee: Heidi J.S. Tworek, History Co-supervisor Robert Brain, History and STS Co-supervisor Supervisory Committee Member Laura Ishiguro, History Additional Examiner ii Abstract This essay traces the development of Sir Sandford Fleming’s Canadian campaign for the Pacific Cable submarine telegraph line from 1879 to 1902. Fleming envisioned a globe-encircling communications network that supported both Canadian economic and political expansion as well as increased inter-colonial partnership between Canada and the Australasian Colonies. Supporting the project through ideologies of nationalism and imperialism, Fleming maintained a broad public discourse in order to encourage funding for the expensive and unpopular telegraph line. The Pacific Cable’s construction during a period of growing political independence across Britain’s white settlement colonies reveals the institutional legacy of the British imperial system within emerging modes of early twentieth-century national development. -

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for October 11Th, 2019

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for October 11th, 2019 For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at: https://electricscotland.com/scotnews.htm Electric Scotland News It is with a heavy heart that I have to inform you all of the passing of Camus-na-h-Erie. Duncan will be posting the following notice in the press soon: Ian Malcolm Grant MacIntyre, 17th Chieftain of Camus-na-h-Erie on 26th September in his 80th year, beloved long term companion of Anne, Countess of Dunmore, loving and adored father of Duncan, Annabelle and Abby, sorely missed by Katie, Rebecca and their families and by his nine grandchildren; Skye, Rosie, Zara, Poppy, Lily, Jack, Kitty, Lulu and Florie. Thanksgiving Service to be held at the Canongate Kirk, Edinburgh on Wednesday 16th October at 2pm. Family flowers only. I will be attending the funeral. I am also aware that the Chief will be represented at the service. I understand it was a heart attack. This is all the information I have at the moment. Regards Colin ------- Scotland and the Arctic Festival Events at Moat Brae Press Release 7th October 2019 Read about this event which includes Inuits from Greenland and also Canada at: https://electricscotland.com/newsletter/moatbrae.pdf Scottish News from this weeks newspapers Note that this is a selection and more can be read in our ScotNews feed on our index page where we list news from the past 1-2 weeks. I am partly doing this to build an archive of modern news from and about Scotland as all the newsletters are archived and also indexed on Google and other search engines. -

A Ripper Deal the Case for Free Trade and Movement Between Australia and the United Kingdom

A Ripper Deal The case for free trade and movement between Australia and the United Kingdom Senator James Paterson A Ripper Deal The case for free trade and movement between Australia and the United Kingdom Senator James Paterson The Adam Smith Institute has an open access policy. Copyright remains with the copyright holder, but users may download, save and distribute this work in any format provided: (1) that the Adam Smith Institute is cited; (2) that the web address adamsmith.org is published together with a prominent copy of this notice; (3) the text is used in full without amendment [extracts may be used for criticism or review]; (4) the work is not re–sold; (5) the link for any online use is sent to info@ adamsmith.org. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect any views held by the publisher or copyright owner. They are published as a contribution to public debate. © Adam Smith Research Trust 2020 CONTENTS Executive summary 6 About the author 9 Preface 10 1 A pivotal time in Britain’s history 12 2 Why Australia will welcome Britain’s return to the global stage 17 3 The future of Australia’s relationship with the UK 23 4 The foundations for a CANZUK agreement 37 Conclusion 46 6 THE ADAM SMITH INSTITUTE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • This is a pivotal time in Britain’s history. The decision to leave the EU allows the UK to redefine its role in the world: to re- emerge as a global champion of free trade and a defender of the rules-based international order. -

From Empire to Commonwealth and League of Nations

FROM EMPIRE TO COMMONWEALTH AND LEAGUE OF NATIONS: INTELLECTUAL ROOTS OF IMPERIALIST- INTERNATIONALISM, 1915-1926 By Martha Aggernaes Ebbesen, Cand.Mag., M.A. July 2019 Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion, Lancaster University This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Acknowledgements: My journey through the history of the British Empire/Commonwealth and the League of Nations has benefitted from a large range of insights and experiences over the past 15 years. In particular, Professor Stuart MacIntyre, showed his old student invaluable help by introducing me to the British World conferences, when I was academically somewhat isolated in Mexico, and Professors Robert Holland and John Darwin gave me valuably advice in the early phases of my work. My supervisors, Professors Michael Hughes and Patrick Bishop, have both offered good and valued guidance as well as kindness and moral support since I enrolled at the University of Lancaster. My father, Professor Sten Ebbesen, has supported me in every possible way, including help with Greek and Latin translations that would otherwise have been beyond me. That this work is written by the daughter of a classicist, should be amply clear along the way. Above all, my thanks to my husband, Juan F Puente Castillo, and our children, Erik, Anna, Daniel and Catalina, who have been patient with me every step of the journey. For better or for worse, this is for you. ABSTRACT During the nineteen-tens and -twenties the British Empire was transformed into the British Commonwealth of Nations and the League of Nations was created and began its work.