UK-EU Foreign Policy Relations: Transiting from Internal Player to External Contestation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents NDPHS Continues Efforts to Have Health Prioritised on The

Northern Dimension Partnership in Public Health A partnership committed to and Social Well-being achieving tangible results e-Newsletter Issue 1/2012 Contents Dear Reader… NDPHS Continues Efforts to It is widely recognised that health is crucial in the context of the ageing Have Health Prioritised on society and challenges posed to sustainable economic development. Yet, the Regional Agenda 1 the importance of health is not properly reflected on the regional coopera- tion agenda. One example is the Action Plan of the EU Strategy for the Baltic The Demography Challenge Sea Region (EUSBSR), where health has been listed as a sub-priority. Since in the Baltic Sea Region 2 last year our Partnership has taken several actions to address this problem Making Success Stories and our efforts will continue. This issue of our e-newsletter will give you with Russian Partners 4 some details on this. Following the above is an article about the 9th Baltic Sea States Summit rd 3 EUSBSR Annual Forum held in May 2012 in Stralsund, Germany and, more specifically, its plenary Discusses the Review of the session on the impact of demographic change. The Prime Ministers had Strategy Action Plan 5 a stimulating debate on main challenges posed by the demographic change PrimCareIT: Counteracting and discussed policies to induce win-win situations for the future. Brain Drain and Professional You will also find two articles about the 3rd Annual Forum of the EU Strat- Isolation of Health 6 egy for the Baltic Sea Region held a few days ago in Denmark. Many interest- ing events took place during it, which provided an opportunity to discuss the progress so far and the way forward. -

A Companion to Nineteenth- Century Britain

A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108, Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, Melbourne, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Chris Williams to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to nineteenth-century Britain / edited by Chris Williams. p. cm. – (Blackwell companions to British history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-22579-X (alk. paper) 1. Great Britain – History – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Great Britain – Civilization – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Williams, Chris, 1963– II. Title. III. Series. DA530.C76 2004 941.081 – dc22 2003021511 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10 on 12 pt Galliard by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published in association with The Historical Association This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of British history. -

Fredrik Reinfeldt

2014 Press release 03 June 2014 Prime Minister's Office REMINDER: German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte to Harpsund On Monday and Tuesday 9-10 June, Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt will host a high-level meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte at Harpsund. The European Union needs to improve job creation and growth now that the EU is gradually recovering from the economic crisis. At the same time, the EU is facing institutional changes with a new European Parliament and a new European Commission taking office in the autumn. Sweden, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands are all reform and growth-oriented countries. As far as Sweden is concerned, it will be important to emphasise structural reforms to boost EU competitiveness, strengthen the Single Market, increase trade relations and promote free movement. These issues will be at the centre of the discussions at Harpsund. Germany, the UK and the Netherlands, like Sweden, are on the World Economic Forum's list of the world's ten most competitive countries. It is natural, therefore, for these countries to come together to compare experiences and discuss EU reform. Programme points: Monday 9 June 18.30 Chancellor Merkel, PM Cameron and PM Rutte arrive at Harpsund; outdoor photo opportunity/door step. Tuesday 10 June 10.30 Joint concluding press conference. Possible further photo opportunities will be announced later. Accreditation is required through the MFA International Press Centre. Applications close on 4 June at 18.00. -

The Brexit Vote: a Divided Nation, a Divided Continent

Sara Hobolt The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Hobolt, Sara (2016) The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23 (9). pp. 1259-1277. ISSN 1466-4429 DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785 © 2016 Routledge This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/67546/ Available in LSE Research Online: November 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent Sara B. Hobolt London School of Economics and Political Science, UK ABSTRACT The outcome of the British referendum on EU membership sent shockwaves through Europe. While Britain is an outlier when it comes to the strength of Euroscepticism, the anti- immigration and anti-establishment sentiments that produced the referendum outcome are gaining strength across Europe. -

AI Hubs: Europe and CANZUK

April 2021 AI Hubs Europe and CANZUK CSET Data Brief AUTHORS Max Langenkamp Melissa Flagg Executive Summary With the increasing importance of artificial intelligence to national and economic security, and the growing competition for AI talent globally, it is essential for U.S. policymakers to understand the landscape of AI talent and investment. This knowledge is critical as U.S. leadership develops new alliances and works to curb the growing influence of China. As an initial effort, an earlier CSET report, “AI Hubs in the United States,” examined the domestic AI ecosystem by mapping where U.S. AI talent is produced, where it is concentrated, and where AI private equity funding goes. That work showed that AI talent and investment was concentrated in specific, well-defined geographic centers referred to as “AI Hubs.” Given the global characteristics of the AI ecosystem and the importance of international talent flows, it is equally important to consider the AI landscape outside of the United States. To provide insights to U.S. policymakers on the larger aspects of international AI talent, this paper builds on our earlier U.S. domestic research by exploring the centers of AI talent and investment in countries and regions that are key U.S. partners: Europe and CANZUK (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom). As before, we examine patterns of investment into privately held AI companies, the geography of top AI research universities, and the location of self-reported AI workers. The key findings: • Traditional treaty partners, including France, Germany, and CANZUK countries, contain both a high number of the top AI research universities and a high number of workers with self-reported AI skills. -

Island Stories

ISLAND STORIES 9781541646926-text.indd 1 11/7/19 2:48 PM ALSO BY DAVID REYNOLDS The Creation of the Anglo-American Alliance: A Study in Competitive Cooperation, 1937–1941 An Ocean Apart: The Relationship between Britain and America in the Twentieth Century (with David Dimbleby) Britannia Overruled: British Policy and World Power in the Twentieth Century The Origins of the Cold War in Europe (editor) Allies at War: The Soviet, American and British Experience, 1939–1945 (co-edited with Warren F. Kimball and A. O. Chubarian) Rich Relations: The American Occupation of Britain, 1942–1945 One World Divisible: A Global History since 1945 From Munich to Pearl Harbor: Roosevelt’s America and the Origins of the Second World War In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War From World War to Cold War: Churchill, Roosevelt and the International History of the 1940s Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century America, Empire of Liberty: A New History FDR’s World: War, Peace, and Legacies (co-edited with David B. Woolner and Warren F. Kimball) The Long Shadow: The Great War and the Twentieth Century Transcending the Cold War: Summits, Statecraft, and the Dissolution of Bipolarity in Europe, 1970–1990 (co-edited with Kristina Spohr) The Kremlin Letters: Stalin’s Wartime Correspondence with Churchill and Roosevelt (with Vladimir Pechatnov) 9781541646926-text.indd 2 11/7/19 2:48 PM ISLAND STORIES AN UNCONVENTIONAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN DAVID REYNOLDS New York 9781541646926-text.indd 3 11/7/19 2:48 PM Copyright © 2020 by David Reynolds Cover design by XXX Cover image [Credit here] Cover copyright © 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc. -

SWEDEN Aras Lindh

★ SWEDEN Aras Lindh Mind Rather Than Heart in EU Politics Highlights ★ The Swedish decision to enter the EU was not based so much on the hope of gaining March 2016 March something, but rather on the fear of being left out if it did not. It was probably the desire for a ‘negative safety’ that made the Swedes vote in favour of the EU as the alternative cost would probably have been too high. ★ Many think that their cutting-edge welfare system and high living standards could be lost as a result of deeper EU integration. This hesitancy towards the EU explains a relative knowledge discrepancy on the EU in the country. Overall, Sweden displays both a degree of satisfaction with its current level of integration (especially its non-membership to the Eurozone) and a diffuse euroscepticism across the society. ★ To strengthen the EU’s image in Sweden requires concrete projects, rather than abstract symbols. A stronger Common European Asylum System would be a prime example of such a project. Overall, any policy from the EU which would positively affect Swedes could decrease scepticism. BUILDING BRIDGES SERIES PAPER Building Bridges project This paper is part of the Building Bridges Paper Series. The series looks at how the Member States perceive the EU and what they expect from it. It is composed of 28 contributions, one from each Member State. The publications aim to be both analytical and educational in order to be available to a wider public. All the contributions and the full volume The European Union in The Fog are available here. -

The Socio-Economic Impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in Times of Corona: the Case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand Kohnert, Dirk

www.ssoar.info The socio-economic impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in times of Corona: The case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand Kohnert, Dirk Preprint / Preprint Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kohnert, D. (2021). The socio-economic impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in times of Corona: The case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand.. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-73206-3 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-SA Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-SA Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Weitergebe unter gleichen (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike). For more Information Bedingungen) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den see: CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de The socio-economic impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in times of Corona : The case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand Dirk Kohnert 1 ‘Britannia as Miss Havisham’ 2 Source: The Guardian / Olusoga, 2017 Abstract: Although Britain has been one of the hardest hit among the EU member states by the corona pandemic, Boris Johnson left the EU at the end of 2020. Brexit supporters endorsed the idea of CANZUK, i.e. a union between the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The CANZUK was embedded in a vision of the revival of the olden days of Great Britain and its role in the ‘Anglosphere’, dating back to World War II and 19th-century British settler colonialism. -

A Nordic Model for Scotland?

A NORDIC MODEL FOR SCOTLAND? Scottish-UK relations after independence Nicola McEwen ESRC Senior Scotland Fellow University of Edinburgh KEY POINTS . Existing UK intergovernmental forums would be insufficient to manage Scottish-rUK intergovernmental relations if the Scottish government’s independence vision was realised. The Nordic example illustrates that intergovernmental cooperation, formal and informal, between neighbouring sovereign states is commonplace in many policy areas. Formal cooperation is most evident where it produces clear ‘added value’ for each party. Formal structures of intergovernmental cooperation nurture policy learning and encourage the networking that facilitates informal cooperation, but senior official and ministerial buy-in can be difficult to secure. European integration has limited the incentive for separate Nordic cooperation initiatives, though Nordic governments continue to cooperate over the implementation of EU directives. The Nordic countries do not usually act as a cohesive regional bloc in the EU – national interests prevail. Intergovernmental coordination among the Nordic countries offers useful insights for Scottish- rUK relations in the event of independence, but the Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers offer limited opportunities for an independent Scotland, either for direct engagement or as a model for Scottish-rUK cooperation. ***** INDEPENDENCE AND INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS For the Scottish government and Yes Scotland, independence would mark a new ‘partnership of equals’ between the nations of these islands. The independence vision, set out in the White Paper, Scotland’s Future, incorporates a variety of proposals for sharing institutional assets and services with the rest of the UK. These include, for example: . Sterling currency union . Research Councils UK . Joint venture between a Scottish Broadcasting . -

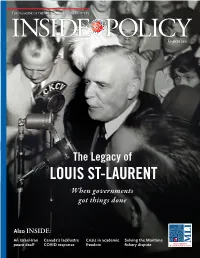

LOUIS ST-LAURENT When Governments Got Things Done

MARCH 2021 The Legacy of LOUIS ST-LAURENT When governments got things done Also INSIDE: An Israel-Iran Canada’s lacklustre Crisis in academic Solving the Maritime peace deal? COVID response freedom fishery dispute 1 PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee LeeBrianby Crowley, Crowley,the Lee Macdonald-Laurier Crowley,Managing Managing Managing Director, Director, Director [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames DeputyAnderson, Anderson, Managing Managing Managing Director, Editor, Editor, Editorial Inside Inside Policy and Policy Operations Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] David McDonough, Deputy Editor James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:Editor, writers: Inside Policy Contributing writers: ThomasThomas S. S.Axworthy Axworthy PastAndrewAndrew contributors Griffith Griffith BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. Axworthy Andrew Griffith Benjamin Perrin Mary-Jane BennettDonaldDonald Barry Barry Jeremy DepowStanleyStanley H. H. Hartt HarttMarcus Kolga MikeMike J.Priaro Berkshire Priaro Miller Massimo BergaminiDonald Barry Peter DeVries Stanley H. HarttAudrey Laporte Mike Priaro Jack Mintz Derek BurneyKenKen Coates Coates Brian Dijkema PaulPaul Kennedy KennedyBrad Lavigne ColinColin RobertsonRobert Robertson P. Murphy Ken Coates Paul Kennedy Colin Robertson Charles Burton Ujjal Dosanjh Ian Lee Dwight Newman BrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley Crowley AudreyAudrey Laporte Laporte RogerRoger Robinson Robinson Catherine -

Britain After Empire

Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Britain After Empire This page intentionally left blank Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Professor of Political Sociology, University of Birmingham, UK © P. W. Preston 2014 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2014 978-1-137-02382-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2014 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

REACHING the SUMMIT International Cooperation Takes Centre Stage in 2021 22715 Steinway ROSL JUN/AUG21 Kravitz.Qxp Layout 1 15/04/2021 11:03 Page 1

ISSUE 726 JUNE - AUGUST 2021 REACHING THE SUMMIT International cooperation takes centre stage in 2021 22715 Steinway ROSL JUN/AUG21 Kravitz.qxp_Layout 1 15/04/2021 11:03 Page 1 WELCOME KRAVITZ GRAND LIMITED EDITION The Royal Over-Seas League is dedicated A COLLABORATION WITH WORLD-RENOWNED MUSICIAN to championing international friendship and understanding through cultural and education “ Whilst travel has AND MODERN-DAY RENAISSANCE MAN LENNY KRAVITZ activities around the Commonwealth and beyond. A not-for-profit private members’ organisation, we’ve been bringing like-minded people been restricted, it's together since 1910. OVERSEAS EDITORIAL TEAM business as usual on Editor Mr Mark Brierley: [email protected]; +44 (0)20 7408 0214 Design the international stage” zed creative: www.zedcreative.co.uk Advertising [email protected] By the time this edition hits the doorstep, ROSL will have reopened its [email protected] doors. After what has been a long and difficult time for members and staff, ROYAL OVER-SEAS LEAGUE we’ll be into a wonderful spring and summer. We’re bursting into action Incorporated by Royal Charter Patron HM The Queen with the addition of two key new members of the team following our Vice-Patron HRH Princess Alexandra KG GCVO decision to take catering back in house – highly experienced Food and President The Rt Hon The Lord Geidt GCB GCVO OBE QSO PC Beverage Manager Serge Pradier, and Executive Chef Elliot Plimmer, who Chairman The Hon. Alexander Downer AC has Michelin starred experience. We will welcome