Language and Territoriality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overzicht Hinder Voor Dienstverlening

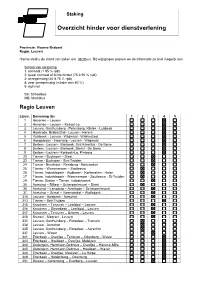

Staking Overzicht hinder voor dienstverlening Provincie: Vlaams-Brabant Regio: Leuven Hierna vindt u de stand van zaken om 06.00uur. Bij wijzigingen passen we de informatie zo snel mogelijk aan. Schaal van verstoring 1: normaal (+ 95 % rijdt) 2: quasi normaal of lichte hinder (75 à 95 % rijdt) 3: onregelmatig (40 à 75 % rijdt) 4: zeer onregelmatig (minder dan 40 %) 5: rijdt niet SB: Schoolbus MB: Marktbus Regio Leuven Lijnnr. Benaming lijn 1 2 3 4 5 1 Heverlee – Leuven 2 Heverlee – Leuven – Kessel-Lo 3 Leuven, Gasthuisberg - Pellenberg, Kliniek - Lubbeek 4 Haasrode, Brabanthal - Leuven - Herent 5 Vaalbeek - Leuven - Wijgmaal - Wakkerzeel 6 Hoegaarden - Neervelp - Leuven - Wijgmaal 7 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Sint-Kamillus - De Borre 8 Bertem - Leuven - Bierbeek, Bremt - De Borre 9 Bertem - Leuven - Korbeek-Lo, Pimberg 22 Tienen – Budingen – Diest 23 Tienen - Budingen - Sint-Truiden 24 Tienen - Neerlinter - Ransberg - Kortenaken 25 Tienen – Wommersom – Zoutleeuw 26 Tienen, Industriepark - Budingen - Kortenaken - Halen 27 Tienen, Industriepark - Wommersom - Zoutleeuw - St-Truiden 29 Tienen, Station – Tienen, Industriepark 35 Aarschot – Rillaar – Scherpenheuvel – Diest 36 Aarschot – Langdorp – Averbode – Scherpenheuvel 37 Aarschot – Gijmel – Varenwinkel – Wolfsdonk 310 Leuven - Holsbeek - Aarschot 313 Tienen – Sint-Truiden 315 Kraainem – Tervuren – Leefdaal – Leuven 316 Kraainem – Sterrebeek – Leefdaal – Leuven 317 Kraainem – Tervuren – Bertem – Leuven 318 Brussel - Moorsel - Leuven 333 Leuven, Gasthuisberg – Rotselaar – Tremelo 334 Leuven -

Une «Flamandisation» De Bruxelles?

Une «flamandisation» de Bruxelles? Alice Romainville Université Libre de Bruxelles RÉSUMÉ Les médias francophones, en couvrant l'actualité politique bruxelloise et à la faveur des (très médiatisés) «conflits» communautaires, évoquent régulièrement les volontés du pouvoir flamand de (re)conquérir Bruxelles, voire une véritable «flamandisation» de la ville. Cet article tente d'éclairer cette question de manière empirique à l'aide de diffé- rents «indicateurs» de la présence flamande à Bruxelles. L'analyse des migrations entre la Flandre, la Wallonie et Bruxelles ces vingt dernières années montre que la population néerlandophone de Bruxelles n'est pas en augmentation. D'autres éléments doivent donc être trouvés pour expliquer ce sentiment d'une présence flamande accrue. Une étude plus poussée des migrations montre une concentration vers le centre de Bruxelles des migrations depuis la Flandre, et les investissements de la Communauté flamande sont également, dans beaucoup de domaines, concentrés dans le centre-ville. On observe en réalité, à défaut d'une véritable «flamandisation», une augmentation de la visibilité de la communauté flamande, à la fois en tant que groupe de population et en tant qu'institution politique. Le «mythe de la flamandisation» prend essence dans cette visibilité accrue, mais aussi dans les réactions francophones à cette visibilité. L'article analyse, au passage, les différentes formes que prend la présence institutionnelle fla- mande dans l'espace urbain, et en particulier dans le domaine culturel, lequel présente à Bruxelles des enjeux particuliers. MOTS-CLÉS: Bruxelles, Communautés, flamandisation, migrations, visibilité, culture ABSTRACT DOES «FLEMISHISATION» THREATEN BRUSSELS? French-speaking media, when covering Brussels' political events, especially on the occasion of (much mediatised) inter-community conflicts, regularly mention the Flemish authorities' will to (re)conquer Brussels, if not a true «flemishisation» of the city. -

Ganshoren Tussen Stad En Natuur

tussen stad Collectie Brussel, Stad van Kunst en Geschiedenis Ganshoren en natuur BRUSSELS HOOFDSTEDELIJK GEWEST 52 De collectie Brussel, Stad van Kunst en Ge- schiedenis wordt uitgegeven om het culturele erfgoed van Brussel ruimere bekendheid te geven. Vol anekdotes, onuitgegeven documenten, oude afbeeldingen, historische gegevens met bijzondere aandacht voor stedenbouw en architectuur vormt deze reeks een echte goudmijn voor de lezer en wandelaar die Brussel beter wil leren kennen. Ganshoren : tussen stad en natuur Het architecturaal erfgoed van de gemeente Ganshoren is gekenmerkt door een opvallende diversiteit. Hieruit blijkt duidelijk hoe sinds het einde van de 19de eeuw op het vlak van ruim- telijke ordening inspanningen zijn geleverd om in deze gemeente van het Brussels Gewest het evenwicht te behouden tussen stad en natuur. Het huidige Ganshoren is het resultaat van opeenvol- gende stedenbouwkundige visies. Dit boek vertelt het verhaal hierachter en neemt de lezer mee op een reis doorheen de boeiende geschiedenis van de Brusselse architectuur en stedenbouw. Charles Picqué, Minister-President van de Regering van het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest belast met Monumenten en Landschappen Stedenboukundige verkenning van een gemeente Ondanks het aparte karakter en de diversiteit van de architectuur op zijn grondgebied blijft de gemeente Ganshoren slecht gekend . Dat is gedeeltelijk te verklaren door zijn perifere ligging . Maar naast die relatieve afgele- genheid is het waarschijnlijk de afstand tussen enerzijds het beeld dat men doorgaans heeft van een stad en anderzijds het feitelijke uitzicht van Ganshoren dat voor verwarring zorgt . Zijn contrastrijke landschap, dat aarzelt tussen stad en platteland, is niet gemakkelijk te vatten . We treffen er zeer duidelijke, zelfs monotone sequenties aan zoals de Keizer Karellaan of de woontorens langs de Van Overbekelaan . -

Language Contact at the Romance-Germanic Language Border

Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Other Books of Interest from Multilingual Matters Beyond Bilingualism: Multilingualism and Multilingual Education Jasone Cenoz and Fred Genesee (eds) Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (eds) Bilingualism: Beyond Basic Principles Jean-Marc Dewaele, Alex Housen and Li wei (eds) Can Threatened Languages be Saved? Joshua Fishman (ed.) Chtimi: The Urban Vernaculars of Northern France Timothy Pooley Community and Communication Sue Wright A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism Philip Herdina and Ulrike Jessner Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism Colin Baker and Sylvia Prys Jones Identity, Insecurity and Image: France and Language Dennis Ager Language, Culture and Communication in Contemporary Europe Charlotte Hoffman (ed.) Language and Society in a Changing Italy Arturo Tosi Language Planning in Malawi, Mozambique and the Philippines Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Planning in Nepal, Taiwan and Sweden Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. and Robert B. Kaplan (eds) Language Planning: From Practice to Theory Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Reclamation Hubisi Nwenmely Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe Christina Bratt Paulston and Donald Peckham (eds) Motivation in Language Planning and Language Policy Dennis Ager Multilingualism in Spain M. Teresa Turell (ed.) The Other Languages of Europe Guus Extra and Durk Gorter (eds) A Reader in French Sociolinguistics Malcolm Offord (ed.) Please contact us for the latest book information: Multilingual Matters, Frankfurt Lodge, Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon, BS21 7HH, England http://www.multilingual-matters.com Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns MULTILINGUAL MATTERS LTD Clevedon • Buffalo • Toronto • Sydney Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Language Contact at Romance-Germanic Language Border/Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns. -

Brussels Aterloose Charleroisestwg

E40 B R20 . Leuvensesteenweg Ninoofsestwg acqmainlaan J D E40 E. oningsstr K Wetstraat E19 an C ark v Belliardstraat Anspachlaan P Brussel Jubelpark Troonstraat Waterloolaan Veeartsenstraat Louizalaan W R20 aversestwg. T Kroonlaan T. V erhaegenstr Livornostraat . W Louizalaan Brussels aterloose Charleroisestwg. steenweg Gen. Louizalaan 99 Avenue Louise Jacqueslaan 1050 Brussels Alsembergsesteenweg Parking: Brugmannlaan Livornostraat 14 Rue de Livourne A 1050 Brussels E19 +32 2 543 31 00 A From Mons/Bergen, Halle or Charleroi D From Leuven or Liège (Brussels South Airport) • Driving from Leuven on the E40 motorway, go straight ahead • Driving from Mons on the E19 motorway, take exit 18 of the towards Brussels, follow the signs for Centre / Institutions Brussels Ring, in the direction of Drogenbos / Uccle. européennes, take the tunnel, and go straight ahead until you • Continue straight ahead for about 4.5 km, following the tramway reach the Schuman roundabout. (the name of the road changes : Rue Prolongée de Stalle, Rue de • Take the 2nd road on the right to Rue de la Loi. Stalle, Avenue Brugmann, Chaussée de Charleroi). • Continue straight on until you cross the Small Ring / Boulevard du • About 250 metres before Place Stéphanie there are traffic lights: at Régent. Turn left and take the small Ring (tunnels). this crossing, turn right into Rue Berckmans. At the next crossing, • See E turn right into Rue de Livourne. • The entrance to the car park is at number 14, 25 m on the left. E Continue • Follow the tunnels and drive towards La Cambre / Ter Kameren B From Ghent (to the right) in the tunnel just after the Louise exit. -

A Forgotten Anniversary: the First European Hypermarkets Open In

Brussels Studies La revue scientifique pour les recherches sur Bruxelles / Het wetenschappelijk tijdschrift voor onderzoek over Brussel / The Journal of Research on Brussels Collection générale | 2013 A forgotten anniversary: the first European hypermarkets open in Brussels in 1961 Un anniversaire oublié : les premiers hypermarchés européens ouvrent à Bruxelles en 1961 Een vergeten verjaardag: de eerste Europese hypermarkten openen in Brussel in 1961 Jean-Pierre Grimmeau Translator: Jane Corrigan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/brussels/1162 DOI: 10.4000/brussels.1162 ISSN: 2031-0293 Publisher Université Saint-Louis Bruxelles Electronic reference Jean-Pierre Grimmeau, « A forgotten anniversary: the first European hypermarkets open in Brussels in 1961 », Brussels Studies [Online], General collection, no 67, Online since 10 June 2013, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/brussels/1162 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/brussels.1162 Licence CC BY www.brusselsstudies.be the e-journal for academic research on Brussels Number 67, June 10th 2013. ISSN 2031-0293 Jean-Pierre Grimmeau A forgotten anniversary: the first European hypermarkets open in Brussels in 1961 Translation: Jane Corrigan Hypermarkets are self-service shops with a surface area of more than 2,500m², which sell food and non food products, are located on the outskirts of a city, are easily accessible and have a large car park. They are generally considered to have been invented in France in 1963 (Carrefour in Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois, close to Paris, 2,500m²). But nearly two years earlier, in 1961, GB had opened three hypermarkets under the name of SuperBazar, in Bruges, Auderghem and Anderlecht, measuring between 3,300 and 9,100m². -

Heritage Days 15 & 16 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS 15 & 16 SEPT. 2018 HERITAGE IS US! The book market! Halles Saint-Géry will be the venue for a book market organised by the Department of Monuments and Sites of Brussels-Capital Region. On 15 and 16 September, from 10h00 to 19h00, you’ll be able to stock up your library and take advantage of some special “Heritage Days” promotions on many titles! Info Featured pictograms DISCOVER Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Regional Public Service of Brussels/Brussels Urbanism and Heritage Opening hours and dates Department of Monuments and Sites a THE HERITAGE OF BRUSSELS CCN – Rue du Progrès/Vooruitgangsstraat 80 – 1035 Brussels c Place of activity Telephone helpline open on 15 and 16 September from 10h00 to 17h00: Launched in 2011, Bruxelles Patrimoines or starting point 02/204.17.69 – Fax: 02/204.15.22 – www.heritagedays.brussels [email protected] – #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel magazine is aimed at all heritage fans, M Metro lines and stops The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers whether or not from Brussels, and reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. T Trams endeavours to showcase the various Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not B Busses aspects of the monuments and sites in bring rucksacks or large bags. -

Directe Tewerkstelling Op Brussels Airport

Directe tewerkstelling op Brussels Airport TRENDRAPPORT 2019/1 Tine Vandekerkhove, Tim Goesaert & Ludo Struyven DIRECTE TEWERKSTELLING OP BRUSSELS AIRPORT Trendrapport 2019/1 Tine Vandekerkhove, Tim Goesaert & Ludo Struyven Onderzoek in opdracht van Aviato Gepubliceerd door KU Leuven HIVA - ONDERZOEKSINSTITUUT VOOR ARBEID EN SAMENLEVING Parkstraat 47 bus 5300, 3000 LEUVEN, België [email protected] http://hiva.kuleuven.be D/2019/4718/017 – ISBN 9789088360909 © 2019 HIVA-KU Leuven Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph, film or any other means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Voorwoord Dit trendrapport over de directe tewerkstelling op Brussels Airport kwam tot stand met de steun van Aviato. Aviato is het tewerkstellingsorgaan van Brussels Airport. Het is een gezamenlijk initiatief dat publieke, privé- en overheidspartners samenbrengt die zich bezighouden met werkgelegenheid en opleiding. De partners zijn VDAB, Actiris, Provincie Vlaams-Brabant, BECI, VOKA, SFTL en Brussels Airport Company. Dit trendrapport is het eerste rapport in een ruimere opdracht van het HIVA-KU Leuven voor Aviato. Als beleidsgerichte onderzoekers willen wij de rol van Aviato versterken als hét kennis- en vaardighedencentrum bij uitstek op het vlak van werk, opleiding en mobiliteit rond de luchthaven. Wij danken de leden van de stuurgroep voor hun waardevolle feedback op eerdere versies van dit eerste trendrapport. In het bijzonder danken wij Aviato voor de deskundige ondersteuning, het geduld en het vertrouwen. Verder danken wij Amynah Gangji van BISA (Brussels Instituut voor Statistiek en Analyse) voor de revisie van de tekst van het Franstalige rapport. -

From Brussels National Airport (Zaventem)

From Brussels National Airport (Zaventem) Æ By taxi - It takes about 20 minutes to get to the CEN premises (longer at rush hour). (cost: approx. 25 €) Æ By train - The Brussels Airport Express to the Central Station (Gare Centrale / Centraal Station) runs approximately every 15 minutes and takes about 25 minutes. (cost: 2,5 €) From the Central Station Æ On foot - It takes about 15 minutes. Æ By taxi - (cost: approx. 7,50 €) Æ By underground (Metro) (cost: 1,40 € for a one way ticket) Take the metro line 1a (yellow) or 1b (red) direction STOCKEL / H. DEBROUX. Change in ARTS-LOI / KUNST WET to metro line 2 (orange) direction CLEMENCEAU. Get off at PORTE DE NAMUR / NAAMSEPOORT, which is at approximately 100 m from the CEN premises. From the South Station (Gare du Midi / Zuidstation) Æ By taxi (cost: approx. 10,00 €) Æ By underground (Metro) (cost: 1,40 € for a one way ticket) Take metro line 2 (orange) direction SIMONIS. Get off at PORTE DE NAMUR / NAAMSEPOORT, which is at approximately 100 m from the CEN premises. Æ Coming from the E19 – Paris: in Drogenbos at sign BRUSSEL/BRUXELLES / INDUSTRIE ANDERLECHT, Exit: 17 - Follow the ramp for about 0,5 km and turn left. Follow Boulevard Industriel for 2 km. Follow the roundabout Rond- Point Hermes for 80 m. Turn right and follow Boulevard Industriel for 1 km. In Saint-Gilles, turn left, follow the Avenue Fonsny for 890 m. In Brussels turn right, and go into the tunnel. Take exit Porte de Namur. At the Porte de Namur turn right into the Chaussée d’Ixelles. -

Multilingual Higher Education in European Regions

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Multilingual higher education in European regions Janssens, R.; Mamadouh, V.; Marácz, L. Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Published in Acta Universitatis Sapientiae. European and Regional Studies Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Janssens, R., Mamadouh, V., & Marácz, L. (2013). Multilingual higher education in European regions. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae. European and Regional Studies, 3, 5-23. http://www.acta.sapientia.ro/acta-euro/C3/euro3-1.pdf General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Acta Universitatis Sapientiae European and Regional Studies Volume 3, 2013 -

A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 B C D E F G H I J a B C D E F G H

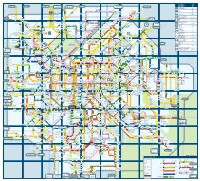

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 POINTS D’INTÉRÊT ARRÊT BEZIENSWAARDIGHEDEN HALTE Asse Puurs via Liezele Humbeek Mechelen Drijpikkel Puurs via Willebroek Luchthaven Malines Malderen Mechelen - Antwerpen POINT OF INTEREST STOP Dendermonde Boom via Londerzeel Kapelle-op-den-Bos Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Antwerpen Malines - Anvers Boom via Tisselt Verbrande Brug Anvers Stade Roi Baudouin Heysel B2 Koning Boudewijn stadion Heizel Jordaen Pellenberg Heysel Ennepetal Minnemolen Sportcomplex Kerk Vilvoorde Heldenplein Atomium B3 Vilvoorde Station 64 Heizel Vlierkens 260 47 58 Kerk Machelen 820 Machelen A 250-251 460-461 A 230-231-232 Twee Leeuwenweg Vilvoorde Heysel Blokken Brussels Expo B3 Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Koningin Fabiola Heizel VTM Drie Fonteinen Parkstraat Aéroport Bruxelles National Windberg Kasteel Luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal Brussels Airport B8 Zellik Station Twyeninck Witloof Beaulieu Raedemaekers Brussels National Airport Dilbeek Keebergen Kaasmarkt Robbrechts Cortenbach Kampenhout RTBF 243-820 Kerk Kortenbach Haacht Diamant D6 Hoogveld VRT Kerk Haren-Sud SAO DGHR Domaine Militaire Omnisports Haren 270-271-470 Markt Bever De Villegas Buda Haren-Zuid Omnisport Haren Basilique de Koekelberg Rijkendal Militair Hospitaal DOO DGHR Militair Domein Dobbelenberg Bossaert-Basilique Gemeenteplein Biplan Basiliek van Koekelberg E2 Guido Gezelle Vijvers Hôpital Militaire 47 Bicoque Aérodrome Bossaert-Basiliek Tweedekker Vliegveld Leuven National Basilica 820 Van Zone tarifaire MTB Louvain 240 Bloemendal Long Bonnier Beyseghem 53 57 -

Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT

Asse Beersel Dilbeek Drogenbos Grimbergen Hoeilaart Kraainem Linkebeek Machelen Meise Merchtem Overijse Sint-Genesius-Rode Sint-Pieters-Leeuw Tervuren Vilvoorde Wemmel Wezembeek-Oppem Zaventem Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering oktober 2011 Samenstelling Diensten voor het Algemeen Regeringsbeleid Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering Cijferboek: Naomi Plevoets Georneth Santos Tekst: Patrick De Klerck Met medewerking van het Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand Verantwoordelijke uitgever Josée Lemaître Administrateur-generaal Boudewijnlaan 30 bus 23 1000 Brussel Depotnummer D/2011/3241/185 http://www.vlaanderen.be/svr INHOUD INLEIDING ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Algemene situering .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Demografie ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aantal inwoners neemt toe ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Aantal huishoudens neemt toe....................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Bevolking is relatief jong én vergrijst verder