Avrahm Galper's Influence on Clarinet Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

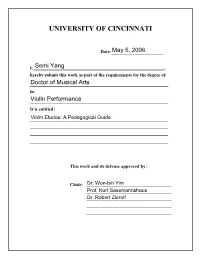

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2019 A master of music recital in clarinet Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2019 Lucas Randall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Randall, Lucas, "A master of music recital in clarinet" (2019). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 1005. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/1005 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MASTER OF MUSIC RECITAL IN CLARINET An Abstract of a Recital Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa December, 2019 This Recital Abstract by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet has been approved as meeting the recital abstract requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Amanda McCandless, Chair, Recital Committee ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Stephen Galyen, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Ann Bradfield, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Jennifer Waldron, Dean, Graduate College This Recital Performance by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet Date of Recital: November 22, 2019 has been approved as meeting the recital requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’S Clarinet Sonata

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata Kenneth T. Aoki Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Composition Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Aoki, Kenneth T., "A Brief History of the Sonata with an Analysis and Comparison of a Brahms’ and Hindemith’s Clarinet Sonata" (1968). All Master's Theses. 1077. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1077 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SONATA WITH AN ANALYSIS AND COMPARISON OF A BRAHMS' AND HINDEMITH'S CLARINET SONATA A Covering Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Music Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Education by Kenneth T. Aoki August, 1968 :N01!83 i iuJ :JV133dS q g re. 'H/ £"Ille; arr THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CENTRAL WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE presents in KENNETH T. AOKI, Clarinet MRS. PATRICIA SMITH, Accompanist PROGRAM Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in B flat Major, Op. 120 No. 2. J. Brahms Allegro amabile Allegro appassionato Andante con moto II Sonatina for Clarinet and Piano .............................................. 8. Heiden Con moto Andante Vivace, ma non troppo Caprice for B flat Clarinet ................................................... -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

Boosey & Hawkes

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Howell, Jocelyn (2016). Boosey & Hawkes: The rise and fall of a wind instrument manufacturing empire. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16081/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Boosey & Hawkes: The Rise and Fall of a Wind Instrument Manufacturing Empire Jocelyn Howell PhD in Music City University London, Department of Music July 2016 Volume 1 of 2 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures...................................................................................................................................... -

The Publication History of Spohr's Clarinet Concertos

THE PUBLICATION HISTORY OF SPOHR'S CLARINET CONCERTOS by Keith Warsop N DISCUSSING the editions used for the recording by French clarinettist paul Meyer of Spohr's four concertos for the instrument on the Alpha label (released as a two-CD set, ALPHA 605, with the orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne), reviewers in the November 2012 issues of the Gramophone and,Internotional Record Review magazines came to some slightly misleading conclusions about this subject so that it has become important to clarify matters. Carl Rosman, writing in 1RR, ,authentic, said: "Meyer has also taken steps towards a more text fbr these concertos. While the clarinet works of Mozart, Brahms and Weber have seen various Urtext editions over the years, Spohr's concertos circulate only in piano reductions from the late nineteenth century ... Meyer has prepared his own editions from the best available sources (the manuscripts of all but No.4 have been lost but there are contemporary manuscript copies of the others held at the Louis Spohr Society in Kassel); this has certainly giu., him lreater freedom in the area of articulation, and also allowed him to adopt some more-flowing temios than the late nineteenth-century editions specify.', In the Gramophone, Nalen Anthoni stated: "Hermstedt demanded exclusive rights and, presumably, kept the autographs. Only that of No.4 was found, in 1960. The other works have been put together from manuscript copies. Paul Meyer seems largely attuned to the solo parts edited by stanley Drucker, the one-time principal ciarinettist of the New york philharmonic. Michael Collins [on the Hyperion label] is of similar mind, though both musicians add their own individual touches phrasing to and articulation. -

Cameron Burgess - Clarinet BBM Youth Support Report - June 2013

Cameron Burgess - Clarinet BBM Youth Support Report - June 2013 My trip to the UK was an incredibly rewarding and exciting experience. In my lessons I gained a wealth of information and ideas on how to perform British clarinet repertoire, and many different approaches and concepts to improve my technique, which I have found invaluable in my development as a musician. I was also able to collect a vast amount of data on Frederick Thurston, who is the focal point of my honours thesis. Much of this information I probably would not have discovered had it not been for my trip to the UK. I was also fortunate enough to attend numerous concerts by the London Symphony Orchestra, Halle Orchestra, London Chamber Orchestra and Southbank Sinfonia, as well as visit London’s many galleries and museums. After arriving in the UK I traveled from Manchester to London for my first lesson, which was with the Principal of the Royal College of Music and renowned Mozart scholar, Professor Colin Lawson. Much of my time in this lesson was devoted to Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto. I had been fortunate enough to attend a master class given by Professor Lawson at the Sydney Conservatorium in 2010 and had gained some ideas on how to interpret the work, however this was expanded on greatly, and my ideas and concepts on how to perform the work completely changed. As well as this we spent some time discussing my thesis topic, how it could potentially be improved and what new ideas I could also include. Professor Lawson also very generously provided me with some incredibly useful literature on Thurston, published for his centenary celebration, which is no longer in print. -

O Ensino Da Clarineta Em Nível Superior: Materiais Didáticos E O Desenvolvimento Técnico-Interpretativo Do Clarinetista

Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima João Pessoa Março de 2019 Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima Orientador: Dr. Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro Trabalho apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal da Paraíba como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música, área de concentração em Educação Musical. João Pessoa Março de 2019 Catalogação na publicação Seção de Catalogação e Classificação L732e Lima, Eduardo Filippe de. O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista / Eduardo Filippe de Lima. - João Pessoa, 2019. 111f. : il. Orientação: Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro. Dissertação (Mestrado) - UFPB/CCTA. 1. Ensino de instrumento musical. 2. Ensino da clarineta em nível superior. 3. Materiais didáticos para clarineta. 4. Desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinet. I. Ribeiro, Fábio Henrique Gomes. II. Título. UFPB/BC 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Gostaria de agradecer imensamente a todos que contribuíram de maneira direta e indireta para a conclusão desse curso de mestrado, o qual me trouxe um profundo amadurecimento pessoal e profissional, e que simboliza o encerramento de mais um ciclo na minha carreira musical. À minha família, que sempre me deu apoio e o suporte necessário para continuar com todos os meus projetos, incluindo esse curso; Ao meu orientador, prof. -

JEAN ANN HITE Résumé, April 2012 440 W. 21St Street, Box 211 New

JEAN ANN HITE Résumé, April 2012 440 W. 21st Street, Box 211 New York, NY 10011 Cell Phone: (239) 980-0912 Email: [email protected] Objective: To obtain a position as a rector or an assistant/associate rector or curate, focusing on reconciliation, teaching and preaching, liturgy and worship, formation and pastoral care Present Status: Transitional Deacon, Episcopal Diocese of SW Florida • Student, The General Theological Seminary (New York City), Class of 2012, Master of Divinity degree program Work Experience: 2011-Present St. Clement’s Episcopal Church, New York, NY: Seminarian Intern • Preaching • Liturgical Diaconal Ministry • Spiritual director 2010–Present The Church of the Epiphany, New York, NY: Seminarian Intern • Adult Education: Class content design and facilitation • Quiet Day Meditations • Liturgical Diaconal Ministry and Evening Prayer Officiant • Preaching • Office and web-site consultation Summer 2011 St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Marco Island, FL: Seminarian Intern • Camp Able (summer camp for disabled children) • Vacation Bible School • Preaching • Pastoral care seminars Summer 2010 Morton Plant Hospital, Clearwater, FL: Clinical Pastoral Education • Hospital Chaplain 2006-2009 St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Bonita Springs, FL: Lay Leadership • Establishment and leadership of Taizé worship • Morning and Evening Prayer Officiant; Lay Reader and Leader • Preaching (weekend Eucharists, Taizé, weekday Eucharists) • Pastoral care representation - Bentley Village, Naples • Nursing home ministry • Lay Eucharistic and Visitation