The Publication History of Spohr's Clarinet Concertos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

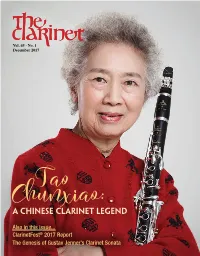

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

Julian Bliss

Julian Bliss “unfailingly musical” Fanfare Magazine Biography Julian Bliss is one of the world’s finest solo clarinettists excelling as concerto soloist, chamber musician, jazz artist, masterclass leader and tireless musical explorer. He has inspired a generation of young players, as guest lecturer and creator of the Leblanc Bliss range of affordable clarinets, and introduced a large new audience to his instrument. The breadth and depth of Julian’s artistry are reflected in the diversity and distinction of his work. He has appeared with many of the world’s leading orchestras, including the London Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, and performed chamber music with Joshua Bell, Hélène Grimaud, Steven Isserlis, Steven Kovacevich and other great interpreters. Born in St Albans (UK), Julian began playing at the age of four. He moved to the United States in 2000 to study at Indiana University and subsequently received lessons from Sabine Meyer in Germany. Julian’s prodigious early career included performances at the prestigious Gstaad, Mecklenburg Vorpommern, Rheingau and Verbier festivals, and critically acclaimed debuts at London’s Wigmore Hall and New York’s Julian Bliss Lincoln Center. His first album for EMI Classics’ Debut series was greeted by five-star reviews and public praise following its release in 2003. Released on Signum Classics in September 2014, Julian’s live recording of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto with the Royal Northern Sinfonia was Classic FM disc of the week upon release. The release was accompanied by a performance at Classic FM Live at the Royal Albert Hall, London. -

English Music for Clarinet and Piano Bax • Fiske • Hamilton • Wood • Bennett

THE THURSTON CONNECTION English Music for Clarinet and Piano Bax • Fiske • Hamilton • Wood • Bennett Nicholas Cox, Clarinet Ian Buckle, Piano The Thurston Connection The Clarinet Sonata, written in 1934, is in two Roger Fiske (1910-1987): Clarinet Sonata English Music for Clarinet and Piano contrasting movements, with a cyclical return of the Sonata’s opening material at the end of the second Roger Fiske was an English musicologist, broadcaster, After starting the clarinet with his father at the age of episode appears to have been forgotten, for he movement. Opening in D major with a sumptuous clarinet author and composer. After taking a BA in English at seven, Frederick Thurston (1901-1953) went on to study immediately summoned Thurston to join the orchestra. melody played over a sonorous piano chord, the initial Wadham College, Oxford in 1932, he studied composition with Charles Draper at the Royal College of Music on an Thurston made a ‘beautiful firm sound’ on his Boosey fourteen bars of the Molto moderato first movement seem with Herbert Howells at the Royal College of Music in Open Scholarship. In the 1920s he played with the Royal and Hawkes wider 10-10 bore clarinets, with which he could to encompass so much harmonically and melodically that London. Awarded an Oxford Doctorate in Music in 1937, Philharmonic Orchestra, the Orchestra of Covent Garden project pianissimo ‘to the back of the Royal Albert Hall’. He one wonders where Bax will subsequently take the he subsequently joined the staff of the BBC where he and the BBC Wireless Orchestra, becoming Principal made relatively few recordings, but those we have suggest listener. -

Download Booklet

573022 bk Ebony Ivory EU_573022 bk Ebony Ivory EU 24/09/2013 12:43 Page 1 Sonatina in G minor for Clarinet and Piano The Clarinet Sonatina, composed in 1948, is Clarinetist Andrew Simon and pianist Warren Lee have been collaborating on stage for over a decade, appearing in dedicated to Frederick Thurston, of whom Arnold tries to numerous recitals for universities, the Hong Kong Chamber Music Society, Buffet-Crampon, Radio Television Hong Born in 1921 in the English town of Northampton, create a miniature portrait in the piece. The opening Kong, and in Macau, Singapore, Australia, Norway, Sweden and the United States. “Together, they produced a rich, Malcolm Arnold developed a keen interest in jazz and at theme depicts the robust and dramatic approach of vibrant and well-balanced sound, characterized by clear articulations, neat phrasing and a finely tuned sense of the age of twelve, decided to take up the trumpet. At the Thurston’s playing, and the music goes on to showcase ensemble,” said the Mercury Post of Australia of a performance of Mozart’s Kegelstatt Trio in May 2011. The Straits Royal College of Music he initially studied trumpet with the best register and character of the instrument. The Times of Singapore described their September 2011 recital as “an unrestrained flourish”. The South China Morning Ernest Hall, as well as composition with Gordon Jacob. three-movement work follows a traditional fast-slow-fast Post of Hong Kong portrayed the duo as “…embody[ing] the solidarity and breadth of local talents.” A fine trumpeter, he joined the London Philharmonic pattern, and is an example of his accessible and light- Orchestra in 1942 after only two years at the College, hearted style among many others. -

Der Kritiker Sagt

SABINE MEYER Clarinet Sabine Meyer is one of the world’s most renowned instrumental soloists. It is partly due to her that the clarinet, a solo instrument previously underestimated, recaptured the attention of the concert platform. Born in Crailsheim, she studied with Otto Hermann in Stuttgart and Hans Deinzer in Hanover, then embarked on a career as an orchestral musician and became member of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. This was followed by an engagement as solo clarinettist at the Berlin Philharmonic which she abandoned, as she was more and more in demand as a soloist. For almost a quarter of a century, numerous concerts and broadcast engagements led her to all musical centres of Europe as well as to Brazil, Israel, Canada, Africa and Australia, and, for twenty years, equally regularly to Japan and the USA. Sabine Meyer has been a much-celebrated soloist with more than three hundred orchestras internationally. She has given guest performances with all the top-level orchestras in Germany and has been engaged by the world’s leading orchestras such as the Vienna Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the NHK Symphony Orchestra Tokyo, the Orchestra of Suisse Romande, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the Radio Orchestras of Vienna, Basel, Warsaw, Prague and Budapest as well as numerous additional ensembles. Sabine Meyer is particularly interested in the field of chamber music, where she has formed much long-lasting collaboration. She has explored a wide range of chamber repertoire with such colleagues as Heinrich Schiff, Gidon Kremer, Oleg Maisenberg, Leif Ove Andsnes, Fazil Say, Martin Helmchen, Juliane Banse, the Hagen Quartet, Tokyo String and Modigliani Quartet. -

Dissertation 3.19.2021

Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Timothy Salzman, Chair David Rahbee Benjamin Lulich Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2021 Caitlin Beare University of Washington Abstract Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Timothy Salzman School of Music The exploration and implementation of new timbral possibilities and techniques over the past century have redefined approaches to clarinet performance and pedagogy. As the body of repertoire involving nontraditional, or “extended,” clarinet techniques has grown, so too has the pedagogical literature on contemporary clarinet performance, yielding method books, dissertations, articles, and online resources. Despite the wealth of resources on extended clarinet techniques, however, few authors offer accessible pedagogical materials that function as a gateway to learning contemporary clarinet techniques and literature. Consequently, many clarinetists may be deterred from learning a significant portion of the repertoire from the past six decades, impeding their musical development. The purpose of this dissertation is to contribute to the pedagogical literature pertaining to extended clarinet techniques. The document consists of two main sections followed by two appendices. The first section (chapters 1-2) contains an introduction and a literature review of extant resources on extended clarinet techniques published between 1965–2020. This literature review forms the basis of the compendium of materials, found in Appendix A of this document, which aims to assist performers and teachers in searching for and selecting pedagogical materials involving extended clarinet techniques. -

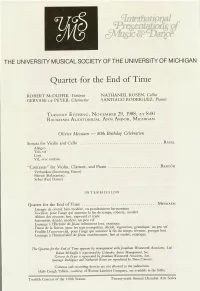

Quartet for the End of Time

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Quartet for the End of Time ROBERT McDUFFIE, Violinist NATHANIEL ROSEN, Cellist GERVASE DE PEYER, Clarinetist SANTIAGO RODRIGUEZ, Pianist TUESDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 29, 1988, AT 8:00 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN Olivier Messiaen 80th Birthday Celebration Sonata for Violin and Cello ......................................... RAVEL Allegro Trcs vif Lent Vif, avec entrain "Contrasts" for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano ......................... BARTOK Verbunkos (Recruiting Dance) Pihend (Relaxation) Sebes (Fast Dance) INTERMISSION Quartet for the End of Time .................................... MESSIAEN Liturgie de cristal; bien modere, en poudroiment harmonieux Vocalise, pour 1'ange qui annonce la fin du temps; robuste, modere Abime des oiseaux; lent, expressif et triste Intermede; decide, modere, un peu vif Louange a 1'Eternite de Jesus; infiniment lent, extatique Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes; decide, vigoureux, granitique, un peu vif Fouillis D'arcs-en-ciel, pour 1'ange qui annonce la fin du temps; revenur, presque lent Louange a rimmortalite de Jesus; extremement, lent et tendre, extatique The Quartet for the End of Time appears by arrangement with Jonathan Wentworth Associates, Ltd. Robert McDuffte is represented by Columbia Artists Management, Inc. Gervase de Peyer is represented by Jonathan Wentworth Associates, Ltd. Santiago Rodriguez and Nathaniel Rosen are represtnted by Shaw Concerts. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner-Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Twelfth Concert of the 110th Season Twenty-sixth Annual Chamber Arts Series PROGRAM NOTES Sonata for Violin and Cello ................................ MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937) Perhaps Mozart's two magnificent Duo Sonatas for Violin and Viola were among the stimuli for Ravel's Sonata for Violin and Cello (also originally entitled Duo). -

Biography the Award-Winning Pianist William Youn

www.williamyoun.com Biography The award-winning pianist William Youn has been described by critics as a “genuine poet” with “sovereign, bravura technique of touch”. After early studies in Korea and in the USA, William again changed continents to study at the Hanover University of Music and at the Piano Academy Lake Como, where he worked regularly with Karl-Heinz Kämmerling, Dmitri Bashkirov, Andreas Staier, William Grant Naboré and Menahem Pressler. Based now in his adopted hometown of Munich, Germany, William performs internationally from Berlin via Seoul to New York with major orchestras, including Cleveland Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Munich Chamber Orchestra, National Orchestra of Belgium, Mariinsky Theater and Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra, and makes regular solo/chamber music appearances in renowned halls, including the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, Pierre Boulez Hall Berlin, Prinzregenten Theater Munich, Konzerthaus Wien, Wigmore Hall London, Toppan Hall Tokyo and Seoul Arts Center, or at festivals such as the Schubertiade, Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, Rheingau Music Festival, Heidelberger Frühling and MDR Musiksommer. William also performs increasingly on fortepiano at venues, including the Mecklenburg Vorpommern Festival, Mozart Festival in Würzburg and Schwetzingen SWR Festival. As chamber musician, William enjoys close collaborations with violist Nils Mönkemeyer, clarinetist Sabine Meyer, cellist Julian Steckel and Johannes Moser, violinist Veronika Eberle and the Signum String Quartet. William has recorded for Sony Korea and Ars Produktion. Other recordings include a disc of works by Brahms with Mönkemeyer, and 'Mozart with Friends' with Sabine Meyer, Julia Fischer and Mönkemeyer, which was named Chamber Music Recording of the Year at ECHO Klassik 2017. -

Instructions for Authors

Journal of Science and Arts Supplement at No. 2(13), pp. 157-161, 2010 THE CLARINET IN THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF THE 20TH CENTURY FELIX CONSTANTIN GOLDBACH Valahia University of Targoviste, Faculty of Science and Arts, Arts Department, 130024, Targoviste, Romania Abstract. The beginning of the 20th century lay under the sign of the economic crises, caused by the great World Wars. Along with them came state reorganizations and political divisions. The most cruel realism, of the unimaginable disasters, culminating with the nuclear bombs, replaced, to a significant extent, the European romanticism and affected the cultural environment, modifying viewpoints, ideals, spiritual and philosophical values, artistic domains. The art of the sounds developed, being supported as well by the multiple possibilities of recording and world distribution, generated by the inventions of this epoch, an excessively technical one, the most important ones being the cinema, the radio, the television and the recordings – electronic or on tape – of the creations and interpretations. Keywords: chamber music of the 20th century, musical styles, cultural tradition. 1. INTRODUCTION Despite all the vicissitudes, music continued to ennoble the human souls. The study of the instruments’ construction features, of the concert halls, the investigation of the sound and the quality of the recordings supported the formation of a series of high-quality performers and the attainment of high performance levels. The international contests organized on instruments led to a selection of the values of the interpretative art. So, the exceptional professional players are no longer rarities. 2. DISCUSSIONS The economic development of the United States of America after the two World Wars, the cultural continuity in countries with tradition, such as England and France, the fast restoration of the West European states, including Germany, represented conditions that allowed the flourishing of musical education. -

British Clarinet Concertos Volume 2 BRITTEN | MATHIAS Finzi | Cooke

BRITISH CLARINET CONCERTOS VOLUME 2 BRITTEN | MATHIAS FINZI | COOKE BBC Symphony Orchestra Michael Collins soloist | conductor New York, December 1941 Benjamin Britten, right, with Peter Pears, at Amityville, Long Island, © T.P. / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library British Clarinet Concertos, Volume 2 Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Movements for a Clarinet Concerto (1941 – 42) 19:20 for Clarinet and Orchestra Devised and orchestrated 2007 by Colin Matthews (b. 1946) Intended for Benny Goodman 1 1 Molto allegro – Tranquillo – Tempo I – Tranquillo – Tempo I – Tranquillo 5:47 2 2 Mazurka elegiaca (derived from Op. 23 No. 2 for two pianos). Poco lento – Animato appassionato – Tempo I – Solenne – Tempo I (poco più lento) 8:12 3 3 Finale. Allegro – Più mosso – Poco più sostenuto – Tempo I – Molto vivo 5:15 3 Gerald Finzi (1901 – 1956) Five Bagatelles, Op. 23a (1938 – 43) 15:33 Arranged 1989 for clarinet and string orchestra by Lawrence Ashmore (1928 – 2013) from the original version for clarinet and piano, Op. 23 4 I Prelude. Allegro deciso – Poco meno mosso – Tempo I 3:30 5 II Romance. Andante tranquillo – Poco più mosso – Tempo I 4:57 6 III Carol. Andantino semplice 2:00 7 IV Forlana. Allegretto grazioso 2:51 8 V Fughetta. Allegro vivace 2:02 Arnold Cooke (1906 – 2005) Concerto No. 1 (1955) 28:08 for Clarinet and String Orchestra in Three Movements To William Morrison 9 I Allegro – Cadenza – A Tempo 11:58 10 II Lento – Poco più mosso – Tempo I 10:37 11 III Allegro vivace – Poco meno mosso – Tempo I 5:26 4 William Mathias (1934 – 1992) Clarinet Concerto, Op. -

English Chamber Orchestra JEFFREY TATE Conductor

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN English Chamber Orchestra JEFFREY TATE Conductor FRANK PETER ZIMMERMANN, Violinist THEA KING, Clarinetist MONDAY EVENING, MARCH 7, 1988, AT 8:00 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Overture to The Marriage of Figaro ................................ MOZART Concerto No. 3 in G major for Violin and Orchestra, K. 216 ........ MOZART Allegro Adagio Rondo: allegro FRANK PETER ZIMMERMANN, Violinist INTERMISSION Mini-Concerto for Clarinet and Strings (1980) ................ GORDON JACOB Allegro Adagio Allegretto moderate Allegro vivace THEA KING, Clarinetist Symphony No. 101 in D major, "The Clock" ....................... HAYDN Adagio, presto Andante Menuetto: allegro Finale: vivace The University Musical Society expresses gratitude to Ford Motor Company Fund for its generosity in underwriting the printing costs of this house program. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner-Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Thirty-third Concert of the 109th Season 109th Annual Choral Union Series PROGRAM NOTES Overture to The Maniave ofFivaro ............ WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Written in 1786, The Marriage ofFigaro is one of Mozart's greatest operas in the Italian style. It embodies Beaumarchais' bitter indictment of the tyranny, greed, and immorality of the nobility. After the sensational success of Beaumarchais' play in Paris in 1784, Mozart suggested to his librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte, the idea of making it into an opera. Already in the autumn of 1785, Mozart was at work on his music, composing with feverish haste, even as Da Ponte hurried to complete the libretto. "As fast as I wrote the words," Da Ponte recounts in his memoirs, "Mozart wrote the music, and it was all finished in six weeks." The overture, however, was composed last, completed only the day before the first performance.