The 1998 Floods in the Tambo Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAIRNSDALE – OMEO East Region – Diocese of Sale Who We Are Tomorrow Begins with What We Do Today

BAIRNSDALE – OMEO East Region – Diocese of Sale Who we are tomorrow begins with what we do today. St Marys Bairnsdale St Patricks Paynesville Vision: We are a welcoming community where the word of God, through the message of Jesus Christ is made known & lived. Our mission is to: L ive the message of Jesus Christ taking inspiration from Mary, the Mother of God. Empower our community to activate their gifts to build a better world. Strengthen and grow our faith. TWELFTH SUNDAY of ORDINARY TIME, Year A – June 21st, 2020 Welcome to all who have joined us to celebrate Mass. St Mary’s Parish Bairnsdale/Omeo acknowledge the Gunai Kurnai people, the Traditional Custodians who have walked upon and cared for this land for thousands of years. We acknowledge the continued deep spiritual attachment and relationship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples to this country and commit ourselves to the ongoing journey of reconciliation. PARISH CONTACTS LITURGY/MASS TIMES Parish Priest: Fr Michael Willemsen ST MARY’S BAIRNSDALE – WEEKDAYS Assistant Priests: Fr Avinash George Mon: 22nd June 9:10am Mass Fr Jayakody Francis Tues: 23rd June 9:10am Mass Bairnsdale Presbytery: Wed: 24th June 9:10am Mass 23 Pyke Street Bairnsdale 3875 Phone 5152 3106 Thurs: 25th June 9:10am Mass Email: [email protected] Fri: 26th June 9:10am Mass Internet: www.stmarysbairnsdale.net ST MARY’S BAIRNSDALE - WEEKENDS Facebook: St Mary's Church Bairnsdale Sat: 27th June 6:00pm St Mary’s Parish Pastoral Centre: Sun: 28th June 9:30am 135 Nicholson Street Bairnsdale 3875 Phone 5152 2942 PLEASE NOTE: No 11am Mass on the 4th Sunday due to Parish Business Manager: Paul Heaton-Harris Masses being held in the High Country. -

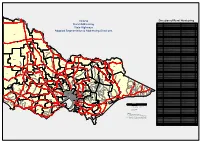

Victoria Rural Addressing State Highways Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions

23 0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 MILDURA Direction of Rural Numbering 0 Victoria 00 00 Highway 00 00 00 Sturt 00 00 00 110 00 Hwy_name From To Distance Bass Highway South Gippsland Hwy @ Lang Lang South Gippsland Hwy @ Leongatha 93 Rural Addressing Bellarine Highway Latrobe Tce (Princes Hwy) @ Geelong Queenscliffe 29 Bonang Road Princes Hwy @ Orbost McKillops Rd @ Bonang 90 Bonang Road McKillops Rd @ Bonang New South Wales State Border 21 Borung Highway Calder Hwy @ Charlton Sunraysia Hwy @ Donald 42 99 State Highways Borung Highway Sunraysia Hwy @ Litchfield Borung Hwy @ Warracknabeal 42 ROBINVALE Calder Borung Highway Henty Hwy @ Warracknabeal Western Highway @ Dimboola 41 Calder Alternative Highway Calder Hwy @ Ravenswood Calder Hwy @ Marong 21 48 BOUNDARY BEND Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions Calder Highway Kyneton-Trentham Rd @ Kyneton McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo 65 0 Calder Highway McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn 73 000000 000000 000000 Calder Highway Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof 62 Murray MILDURA Calder Highway Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake 77 Calder Highway Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen 88 Calder Highway Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura 99 Calder Highway Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura Murray River @ Yelta 23 Glenelg Highway Midland Hwy @ Ballarat Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham 76 OUYEN Highway 0 0 97 000000 PIANGIL Glenelg Highway Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham Lonsdale -

Gauging Station Index

Site Details Flow/Volume Height/Elevation NSW River Basins: Gauging Station Details Other No. of Area Data Data Site ID Sitename Cat Commence Ceased Status Owner Lat Long Datum Start Date End Date Start Date End Date Data Gaugings (km2) (Years) (Years) 1102001 Homestead Creek at Fowlers Gap C 7/08/1972 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 19.9 -31.0848 141.6974 GDA94 07/08/1972 16/12/1995 23.4 01/01/1972 01/01/1996 24 Rn 1102002 Frieslich Creek at Frieslich Dam C 21/10/1976 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 8 -31.0660 141.6690 GDA94 19/03/1977 31/05/2003 26.2 01/01/1977 01/01/2004 27 Rn 1102003 Fowlers Creek at Fowlers Gap C 13/05/1980 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 384 -31.0856 141.7131 GDA94 28/02/1992 07/12/1992 0.8 01/05/1980 01/01/1993 12.7 Basin 201: Tweed River Basin 201001 Oxley River at Eungella A 21/05/1947 Open DWR 213 -28.3537 153.2931 GDA94 03/03/1957 08/11/2010 53.7 30/12/1899 08/11/2010 110.9 Rn 388 201002 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.1 C 27/05/1947 31/07/1957 Closed DWR 124 -28.3151 153.3511 GDA94 01/05/1947 01/04/1957 9.9 48 201003 Tweed River at Braeside C 20/08/1951 31/12/1968 Closed DWR 298 -28.3960 153.3369 GDA94 01/08/1951 01/01/1969 17.4 126 201004 Tweed River at Kunghur C 14/05/1954 2/06/1982 Closed DWR 49 -28.4702 153.2547 GDA94 01/08/1954 01/07/1982 27.9 196 201005 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.3 A 3/04/1957 Open DWR 111 -28.3096 153.3360 GDA94 03/04/1957 08/11/2010 53.6 01/01/1957 01/01/2010 53 261 201006 Oxley River at Tyalgum C 5/05/1969 12/08/1982 Closed DWR 153 -28.3526 153.2245 GDA94 01/06/1969 01/09/1982 13.3 108 201007 Hopping Dick Creek -

2013-2014 to 2015-2016 Ovens

Y RIV A E W RIN A H HIG H G WAY I H E M U H THOLOGOLONG - KURRAJONG TRK HAW KINS STR Y EET A W H F G L I A G H G E Y C M R E U E H K W A Y G A R A W C H R G E I E H K R E IV E M R U IN H A H IG MURR H AY VAL W LEY HI A GHWAY Y MA IN S TR EE K MURRAY RIVER Y E T A W E H R C IG N H E O THOLOGOLONG - BUNGIL REFERENCE AREA M T U S WISES CREEK - FLORA RESERVE H N H AY O W J MUR IGH RAY V A H K ALLEY RIN E HIGH IVE E WAY B R R ORE C LLA R P OAD Y ADM B AN D U RIVE R Y A D E W M E A W S IS N E C U N RE A U EK C N L Grevillia Track O Chiltern - Wallaces Gully C IN L Kurrajong Gap Wodonga Wodonga McFarlands Hill ! GRANYA - FIREBRACE LINK TRACK Chiltern Red Box Track Centre Tk GRANYA BRIDLE TK AN Z K AC E E PA R R C H A UON A HINDLETON - GRANYA GAP ROAD CREEK D G E N M A I T H T T A E B Chiltern Caledenia plots - All Nations road M I T T A GEORGES CREEK HILLAS TK R Chiltern Caledenia plots - All Nations road I V E Chiltern Skeleton Hill R Wodonga WRENS orchid block K E Baranduda Stringybark Block E R C Peechelba Frosts E HOUSE CREEK L D B ID Y M Boorhaman Native Grassland E C K Barambogie - Sandersons hill - grassland R EE E R C Barambogie - Sandersons hill - forest E G K N RI SP Brewers Road Baranduda Trig Point Track Cheesley Gate road HWAY HIG D LEY E VAL E RAY P K UR M C E Dry Forest Ck - Ref. -

GO on > HEAD EAST

industry & investment > EAST GIPPSLAND GO ON > HEAD EAST. www.discovereastgippsland.com.au 1 < GO ON > HEAD EAST BEACH, BEACH HAPPY & MORE BEACH. DAYS. HOME to AustRALIA’S Longest beach (90 MILE Beach) AND YEAR ROUND LARgest INLAND wateRwaY TEMPERATE CLIMATE (THE GIPPSLAND LAKES) TOWNS & COMMUNITIES. 8 MAJOR towns AND AROUND 40 INDIViduaL COMMUNITIES 30 PRIMARY, 6 secondaRY SCHOOLS & ACCESS to TERTIARY education LocaLLY MEDIAN HOUSE PRICE $230,000* HOME to ONE OF THE LARgest FISHING PORts IN AustRALIA ALIVE WITH NATURE & WILDLIFE. ONE OF THE LARGEST AREAS OF NationaL PARKS IN AustRALIA – 1.5 MILLION hectaRES ONE OF THE LARgest PER TRAIN: MELBOURNE capita boat owneRSHIPS to BAIRnsdaLE 3 IN AustRALIA TIMES daiLY (3.5 HOUR JOURNEy) * SOURCE: BAIRNsdaLE, RP Data, MARCH 2014 > 2 welcome > EAST GIPPSLAND HEAD EAST & EXPERIENCE > A better work/life balance > A more relaxed lifestyle with time to enjoy our diverse natural wonders > Affordable housing so you can spend more money on the things you want > A chance to further your career in a thriving and vibrant community > Excellent educational facilities for your children to help deliver a bright, successful future welcome to Home to tranquil lakes, pristine beacHes and tHe rugged beauty of tHe HigH country. east gippsland WHETHER YOU HAVE A LIFETIME, A MONTH, A WEEKEND OR A daY, THERE ARE MANY Reasons to EXploRE THIS MagiCAL CORNER OF VICtoRIA. Our relaxed regional lifestyle means that you can forget about traffic jams and get home on time to enjoy everything the region has to offer. Spend time with family and friends or head outdoors for some quality “me” time. -

Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations

LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL RIVERS AND STREAMS SPECIAL INVESTIGATION FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS June 1991 This text is a facsimile of the former Land Conservation Council’s Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations. It has been edited to incorporate Government decisions on the recommendations made by Order in Council dated 7 July 1992, and subsequent formal amendments. Added text is shown underlined; deleted text is shown struck through. Annotations [in brackets] explain the origins of the changes. MEMBERS OF THE LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL D.H.F. Scott, B.A. (Chairman) R.W. Campbell, B.Vet.Sc., M.B.A.; Director - Natural Resource Systems, Department of Conservation and Environment (Deputy Chairman) D.M. Calder, M.Sc., Ph.D., M.I.Biol. W.A. Chamley, B.Sc., D.Phil.; Director - Fisheries Management, Department of Conservation and Environment S.M. Ferguson, M.B.E. M.D.A. Gregson, E.D., M.A.F., Aus.I.M.M.; General Manager - Minerals, Department of Manufacturing and Industry Development A.E.K. Hingston, B.Behav.Sc., M.Env.Stud., Cert.Hort. P. Jerome, B.A., Dip.T.R.P., M.A.; Director - Regional Planning, Department of Planning and Housing M.N. Kinsella, B.Ag.Sc., M.Sci., F.A.I.A.S.; Manager - Quarantine and Inspection Services, Department of Agriculture K.J. Langford, B.Eng.(Ag)., Ph.D , General Manager - Rural Water Commission R.D. Malcolmson, M.B.E., B.Sc., F.A.I.M., M.I.P.M.A., M.Inst.P., M.A.I.P. D.S. Saunders, B.Agr.Sc., M.A.I.A.S.; Director - National Parks and Public Land, Department of Conservation and Environment K.J. -

Eligible Schools – South Eastern Victoria

ELIGIBLE SCHOOLS – SOUTH EASTERN VICTORIA Category 1 Schools Airly PS Drouin South PS Lindenow South PS Noorinbee PS Swifts Creek P-12 School Alberton PS Drouin West PS Loch PS Nowa Nowa PS Tambo Upper PS Araluen PS Eagle Point PS Loch Sport PS Nungurner PS Tanjil South PS East Gippsland Specialist Bairnsdale PS School Longford PS Nyora PS Tarwin Lower PS Bairnsdale SC Ellinbank PS Longwarry PS Omeo PS Tarwin Valley PS Bairnsdale West PS Fish Creek and District PS Lucknow PS Orbost North PS Thorpdale PS Boisdale Consolidated School Foster PS Maffra PS Orbost PS Toora PS Goongerah Tubbut P–8 Bona Vista PS College Maffra SC Orbost SC Toorloo Arm PS Briagolong PS Gormandale And District PS Mallacoota P-12 College Paynesville PS Trafalgar High School Bruthen PS Guthridge PS Marlo PS Perseverance PS Trafalgar PS Buchan PS Heyfield PS Metung PS Poowong Consolidated School Warragul & District Specialist School Buln Buln PS Jindivick PS Mirboo North PS Rawson PS Warragul North PS Bundalaguah PS Kongwak PS Mirboo North SC Ripplebrook PS Warragul PS Cann River P-12 College Korumburra PS Nambrok Denison PS Rosedale PS Warragul Regional College Clifton Creek PS Korumburra SC Narracan PS Sale College Welshpool and District PS Cobains PS Labertouche PS Neerim District Rural PS Sale PS Willow Grove PS Cowwarr PS Lakes Entrance PS Neerim District SC Sale Specialist School Woodside PS Dargo PS Lakes Entrance SC Neerim South PS Seaspray PS Wurruk PS Darnum PS Lardner and District PS Newmerella PS South Gippsland SC Yarragon PS Devon North PS Leongatha PS -

The Geology and Prospectivity of the Tallangatta 1:250 000 Sheet

VIMP Report 10 The geology and prospectivity of the Tallangatta 1:250 000 sheet I.D. Oppy, R.A. Cayley & J. Caluzzi November 1995 Bibliographic reference: OPPY, I.D., CAYLEY R.A. & CALUZZI, J., 1995. The Geology and prospectivity of the Tallangatta 1:250 000 sheet Victorian Initiative for Minerals and Petroleum Report 10. Department of Agriculture, Energy and Minerals. © Crown (State of Victoria) Copyright 1995 Geological Survey of Victoria ISSN 1323 4536 ISBN 0 7306 7980 2 This report may be purchased from: Business Centre, Department of Agriculture, Energy & Minerals, Ground Floor, 115 Victoria Parade, Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 For further technical information contact: General Manager, Geological Survey of Victoria, Department of Agriculture, Energy & Minerals, P O Box 2145, MDC Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 Acknowledgments: The authors wish to acknowledge G. Ellis for formatting the document, R. Buckley, P.J. O'Shea and D.H. Taylor for editing and S. Heeps for cartography I. Oppy wrote chapters 3 and 5, R. Cayley wrote chapter 2 and J. Caluzzi wrote chapter 4. GEOLOGY AND PROSPECTIVITY - TALLANGATTA 1 Contents Abstract 4 1 Introduction 5 2 Geology 7 2.1 Geological history 7 Pre-Ordovician to Early Silurian 7 Early Silurian Benambran deformation and widespread granite intrusion 8 Middle to Late Silurian 9 Late Silurian Bindian deformation 9 Early Devonian rifting and volcanism 10 Middle Devonian Tabberabberan deformation 11 Late Devonian sedimentation and volcanism 11 Early Carboniferous Kanimblan deformation to Present day 11 2.2 Stratigraphy -

Regional Camping Guide

Guide to Free Camping Sites in North East Victoria Encompassing the regions of... Albury Wodonga, Lake Hume, Chiltern, Rutherglen, Wahgunyah, Beechworth, Yackandandah, Bright, Myrtleford, Mt Beauty, Wangaratta, Benalla, Tallangatta, Corryong, Dartmouth, Mansfield. 7 1 2 3 8 5 6 4 Mansfield Region 1 Blue Range Camping and Picnic Area Blue Range offers a small basic camp site on Blue Range Creek. (Creek may run low in summer). Directions: From Mansfield: Head north on Mansfield-Whitfield Rd approx. 10km to Mt Samaria Park turnoff, continue 4.4km north on Blue Range Rd (unsealed - keep left at 0.7k), towards Mt Samaria Park, camp on the right before entering Park. 2 Buttercup Creek Camping Area Small camping areas alongside Buttercup Creek offering shady location. Directions: From Mansfield: Head east on Mt Buller Rd through Sawmill Settlement, left (north) 5.4k on Carters Rd (unsealed), left (west) 0.7k down Buttercup Rd to the first site, 4 more sites over the next 4k, all on the right. 3 Carters Mill Camping and Picnic Area Camping area at Carters Mill is a small, sheltered site close to the Delatite River. Directions: From Mansfield: Head east on Mt Buller Rd through Sawmill Settlement, left (north) on Carters Rd (unsealed), cross Plain Creek, signed access track on right. 4 The Delatite Arm Reserve The Delatite Arm Reserve (also known as The Pines) is situated along the shores of Lake Eildon and adjacent to bushland. The reserve is very popular for camping, water sports, scenic views and fishing .Access to lake. Informal boat ramps. Directions: From Mansfield: From Mansfield east on Mt Buller Rd 4km, south on Mansfield – Woods Point Rd for 9.5km and turn right (west) on Piries - Gough’s Bay Rd. -

Heritage Rivers Act 1992 No

Version No. 014 Heritage Rivers Act 1992 No. 36 of 1992 Version incorporating amendments as at 7 December 2007 TABLE OF PROVISIONS Section Page 1 Purpose 1 2 Commencement 1 3 Definitions 1 4 Crown to be bound 4 5 Heritage river areas 4 6 Natural catchment areas 4 7 Powers and duties of managing authorities 4 8 Management plans 5 8A Disallowance of management plan or part of a management plan 7 8B Effect of disallowance of management plan or part of a management plan 8 8C Notice of disallowance of management plan or part of a management plan 8 9 Contents of management plans 8 10 Land and water uses which are not permitted in heritage river areas 8 11 Specific land and water uses for particular heritage river areas 9 12 Land and water uses which are not permitted in natural catchment areas 9 13 Specific land and water uses for particular natural catchment areas 10 14 Public land in a heritage river area or natural catchment area is not to be disposed of 11 15 Act to prevail over inconsistent provisions 11 16 Managing authority may act in an emergency 11 17 Power to enter into agreements 12 18 Regulations 12 19–21 Repealed 13 22 Transitional provision 13 23 Further transitional and savings provisions 14 __________________ i Section Page SCHEDULES 15 SCHEDULE 1—Heritage River Areas 15 SCHEDULE 2—Natural Catchment Areas 21 SCHEDULE 3—Restricted Land and Water Uses in Heritage River Areas 25 SCHEDULE 4—Specific Land and Water Uses for Particular Heritage River Areas 27 SCHEDULE 5—Specific Land and Water Uses for Particular Natural Catchment Areas 30 ═══════════════ ENDNOTES 31 1. -

Supporting Information for Section 3.3

Appendix E – Supporting Information for Section 3.3 GHD | Report for Latrobe City Council –Hyland Highway Landfill Extension, 3136742 Gippsland Waste and Resource Recovery Implementation Plan June 2017 Section 6: Infrastructure Schedule Section 6 | Infrastructure Schedule 6. Infrastructure Schedule As a requirement of the EP Act, the Gippsland Implementation Plan must include an Infrastructure Schedule that outlines existing waste and resource infrastructure within the region and provides detail on what will be required to effectively manage Gippsland’s future waste needs. The purpose of the Schedule is to facilitate planning to identify and address gaps in infrastructure based on current status, future needs, and constraints and opportunities. In developing this Schedule, the region has worked with the other Waste and Resource Recovery Groups, ensuring consistency and alignment with the Infrastructure Schedules across the state. A key requirement of the Infrastructure Schedule is to facilitate decision making that prioritises resource recovery over landfilling. To the knowledge of the GWRRG, all relevant facilities currently in existence have been included in the Schedule. It is important to note that inclusion of a facility should not in any way be interpreted as a warranty or representation as to its quality, compliance, effectiveness or suitability. While the GWRRG has made every effort to ensure the information contained in the Infrastructure Schedule is accurate and complete, the list of facilities included, as well as information and comments in the ‘other considerations’ section, should not be taken as exhaustive and are provided to fulfil the objectives of the EP Act. Further information about individual facilities should be sought from the EPA or (where appropriate) owners or operators of facilities. -

Planting Guide Tambo River Swifts Creek to Bruthen

Tambo River Swifts Creek Township to Bruthen (including Sheep Station Creek and Back Creek). Larger trees with deep root Medium sized plants with Low growing plants with systems good root systems, providing matted roots to bind the bank toe stream shade and help control erosion Top of bank Bank slope Toe of bank (mid-bank) (water’s edge) Trees Trees Trees -Silver Wattle -Lightwood -Silver Wattle -Lightwood -Silver Wattle -Blackwood -Blackwood -Manna Gum -Blackwood -Manna Gum -Manna Gum -Yellow Box -Apple Box -Yellow Box -Apple Box -Bundy (Eucalyptus -Red Stringybark -Mountain Grey goniocalyx) -Mountain Grey Gum Gum Small trees and large shrubs Small trees and large shrubs Small trees and large shrubs -Black Wattle -Kanooka -Black Wattle -Woolley Tea-tree -Woolley Tea-tree -Rough-barked -Tree Hakea -Sunshine Wattle -Rough-barked -Kanooka Honey-Myrtle -Cherry Ballart -Varnish Wattle Honey-Myrtle -Tree Hakea -Sunshine Wattle -Varnish Wattle Small shrubs and herbs Small shrubs and herbs Small shrubs and herbs 1 – 4 metres 1 – 4 metres 1 – 4 metres -Eastern Bitter- -Shiny Cassinia -Eastern Bitter- -Shiny Cassinia -Eastern Bitter- -River Bottle-brush bush -Purple Coral-pea bush -Purple Coral-pea bush -Sweet Bursaria -Narrow-leaved Hop -Burgan -Narrow-leaved Hop -Burgan -Burgan Bush -Austral Indigo Bush -Austral Indigo -Snowy Daisy-bush -Snowy Daisy-bush -Sweet Bursaria -Sweet Bursaria CLIMBERS: CLIMBERS: -Skeleton Vine -Skeleton Vine Clematis Clematis -Forest Clematis -Forest Clematis Grasses/reeds/sedges Grasses/reeds/sedges Grasses/reeds/sedges