Caravaggio's Two St. Matthews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hassler's Roma: a Publication That Descrive Tutte Le Meraviglie Intorno Al Nostro Al- Describes All the Marvels, Both Hidden and Not, Bergo, Nascoste E Non

HASSLER’S ROMA A CURA DI FILIPPO COSMELLI Prodotto in esclusiva per l’Hotel Hassler direzione creativa: Filippo Cosmelli direzione editoriale: Daniela Bianco fotografie: Alessandro Celani testi: Filippo Cosmelli & Giacomo Levi ricerche iconografiche: Pietro Aldobrandini traduzione: Logos Srls. - Creative services assistente: Carmen Mariel Di Buono mappe disegnate a mano: Mario Camerini progetto grafico: Leonardo Magrelli stampato presso: Varigrafica, Roma Tutti I Diritti Riservati Nessuna parte di questo libro può essere riprodotta in nessuna forma senza il preventivo permesso da parte dell’Hotel Hassler 2018. If/Books · Marchio di Proprietà di If S.r.l. Via di Parione 17, 00186 Roma · www.ifbooks.it Gentilissimi ospiti, cari amici, Dear guests, dear friends, Le strade, le piazze e i monumenti che circonda- The streets, squares and buildings that surround no l’Hotel Hassler sono senza dubbio parte inte- the Hassler Hotel are without a doubt an in- grante della nostra identità. Attraversando ogni tegral part of our identity. Crossing Trinità de mattina la piazza di Trinità de Monti, circonda- Monti every morning, surrounded by the stair- ta dalla scalinata, dal verde brillante del Pincio case, the brilliant greenery of the Pincio and the e dalla quiete di via Gregoriana, è inevitabile silence of Via Gregoriana, the desire to preser- che sorga il desiderio di preservare, e traman- ve and hand so much beauty down to future ge- dare tanta bellezza. È per questo che sono feli- nerations is inevitable. This is why I am pleased ce di presentarvi Hassler’s Roma: un volume che to present Hassler's Roma: a publication that descrive tutte le meraviglie intorno al nostro al- describes all the marvels, both hidden and not, bergo, nascoste e non. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

Santa Maria Del Popolo Piazza Del Popolo Metro Station: Flaminio, Line a 7 AM – 12 PM (Closed Sunday) 4 PM – 7 PM (Closed Sunday)

Santa Maria del Popolo Piazza del Popolo Metro station: Flaminio, line A 7 AM – 12 PM (Closed Sunday) 4 PM – 7 PM (Closed Sunday) Sculpture of Habakkuk and the Angel by Bernini (after 1652) in the Chigi Chapel Crucifixion of St. Peter (1600-01) by Caravaggio in the Cerasi Chapel. Baroque facade added by Bernini in 1600 Standing on the Piazza del Popolo, near the northern gate of the Aurelian Wall, the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo is a small temple with a splendid Renaissance decoration in its interior. In its interior Santa Maria del Popolo’s decoration is unlike any other church in Rome. The ceiling, less high than most built during the same period, is practically bare, while the decoration of each of the small chapels is especially remarkable. Among the beautiful art work found in the church, it is worth highlighting the Chapel Cerasi, which houses two canvases by Caravaggio from 1600, and the Chapel Chigi, built and decorated by Raphael. If you look closely at the wooden benches, you’ll be able to see inscriptions with the names of the people the benches are dedicated to. This custom is also found in a lot of English speaking countries like Scotland or Edinburgh, where the families of the person deceased buy urban furniture in their honour. ******************************************** Located next to the northern gate of Rome on the elegant Piazza del Popolo, the 15th-century Santa Maria del Popolo is famed for its wealth of Renaissance art. Its walls and ceilings are decorated with paintings by some of the greatest artists ever to work in Rome: Pinturicchio, Raphael, Carracci, Caravaggio and Bernini. -

Caravaggio's Capitoline Saint John

Caravaggio’s Capitoline Saint John: An Emblematic Image of Divine Love Shannon Pritchard With an oeuvre filled with striking, even shocking works, mid-1601 on the invitation of the Roman Marchese Ciriaco Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Saint John the Baptist Mattei and his two brothers, Cardinal Girolamo Mattei and in the Wilderness, still remains one of his most visually com- Asdrubale Mattei, and remained there for approximately two pelling works (Figure 1).1 The painting, now in the Capitoline years.4 Thirteen years later, his painting was recorded in the Museum in Rome, was completed around 1601-02 during the 1616 inventory of Ciriaco’s only son and heir, Giovanni Battista height of the artist’s Roman career.2 At first glance, the nude Mattei, at which time it was listed as “Saint John the Baptist figure, splayed from corner to corner across the entire canvas, with his lamb by the hand of Caravaggio.”5 From this point produces an uneasy response in the viewer. The boy’s soft, forward, the painting is documented in numerous invento- curly hair, prepubescent body and coquettish turn of the head ries, and these records reveal that uncertainty over the subject endow the image with an unexpected sensuality. It is precisely matter was present virtually from the beginning. In 1623, this quality that has spawned nearly four hundred years of Giovanni Battista Mattei bequeathed the painting to Cardinal debate about the identity of Caravaggio’s nude youth, the sup- Francesco Maria del Monte, in whose 1627 inventory it was posed John the Baptist. -

Apostle to the Gentiles” Has Begun

50 Copyright © 2010 Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University Due to copyright restrictions, this image is only available in the print version of Racism. In Caravaggio’s painting, Saul is knocked flat on his back before our eyes and almost into our space. His suffering as the “apostle to the Gentiles” has begun. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1573-1610), THE CONVERSION OF ST. PAUL (1600-1601). Oil on canvas, 90½ ” x 70”. Cerasi Chapel, S. Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy. Photo: © Scala / Art Resource, NY. Used by permission. © 2010 Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University Apostle to the Gentiles BY HEIDI J. HORNIK aravaggio painted The Conversion of St. Paul as a pair with Crucifixion of St. Peter to establish a theme of suffering. The suffering of Peter, Cthe apostle to the Jews, as he is crucified upside down on a cross is immediately apparent. As the apostle to the Gentiles, Paul endured suffering and ridicule as he took the gospel to those outside the Jewish faith. Monsignor Tiberio Cerasi, treasurer general under Pope Clement VIII, com- missioned Caravaggio to paint the two pictures in his recently acquired private chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome. On September 24, 1600, Caravaggio signed a contract to paint them on two cypress panels measuring 10 x 8 palmi.† Keeping close to the details in the biblical accounts of the apostle’s con- version (Acts 9:1-6, 22:5-11, 26:13), Caravaggio does not embellish the narrative with an apparition of God or angels. The psychological dimension of the painting is very modern: Saul, the Jewish persecutor of Christians, is knocked flat on his back before our eyes and almost into our space. -

1 Caravaggio and a Neuroarthistory Of

CARAVAGGIO AND A NEUROARTHISTORY OF ENGAGEMENT Kajsa Berg A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia September 2009 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior written consent. 1 Abstract ABSTRACT John Onians, David Freedberg and Norman Bryson have all suggested that neuroscience may be particularly useful in examining emotional responses to art. This thesis presents a neuroarthistorical approach to viewer engagement in order to examine Caravaggio’s paintings and the responses of early-seventeenth-century viewers in Rome. Data concerning mirror neurons suggests that people engaged empathetically with Caravaggio’s paintings because of his innovative use of movement. While spiritual exercises have been connected to Caravaggio’s interpretation of subject matter, knowledge about neural plasticity (how the brain changes as a result of experience and training), indicates that people who continually practiced these exercises would be more susceptible to emotionally engaging imagery. The thesis develops Baxandall’s concept of the ‘period eye’ in order to demonstrate that neuroscience is useful in context specific art-historical queries. Applying data concerning the ‘contextual brain’ facilitates the examination of both the cognitive skills and the emotional factors involved in viewer engagement. The skilful rendering of gestures and expressions was a part of the artist’s repertoire and Artemisia Gentileschi’s adaptation of the violent action emphasised in Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes testifies to her engagement with his painting. -

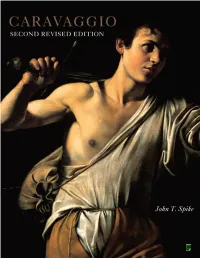

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Caravaggism in the Work of Guido Reni Man Ltmdrns

Caravaggism in the Work of Guido Reni Man ltmdrns An important key to understanding Guido Reni's personal theme was the revival of e.irly Chiistian roots. This painting, style is his interest in opposing qualities. These opposites in lauded for gentleness that the 01iginal lacked, in addition to the clude his representation of tensions between lhe heavenly and 1601 Martyrdom ofSt. Cecilia and Com11atio11 ofSts. Cecilia temporal. holy grace u-iumphant over an earthly morass. vii1u and Valerian gave Rcni popularity which extended. for the first ous physical beauty versus the execrated Christian body. On time, beyond Bologna. By looking at these. we can see 1ha1 this partially autobiographical element of Reni's Style, very linlc Reni called upon the simple, rigid sy1mnetry of early Christian has been w1i11en in depth, although there is some mention of paintings as well as the trend of local interest in tenebrism. this dialectic in most of the literature on Reni. Of those slight Also at this Lime, the Cavaliere d'Arpino was instn1mental obligatory references, most discuss composition and the op in obtaining important pau-onage for Reni. He did this 10 over posing relation of Caravaggio's style to Rcni's. If a similarity shadow the growing success of Caravaggio. By I 602. Reni between the artists is mentioned. it is usually in reference to was sraning to work Loward a more expressive naturalism of Ren i's 1604 Crucifixjo11 ofS1. Pe1er (Figure I) or. in a few cases, his own. The rigid compositions of the Saint Cecilia paintings the 1606 Da,,id with 11te Head of Goliath. -

Gli Esordi Di Caravaggio a Roma

Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana Band 39 ∙ 2009/2010 LOTHAR SICKEL GLI ESORDI DI CARAVAGGIO A ROMA UNA RICOSTRUZIONE DEL SUO AMBIENTE SOCIALE NEL PRIMO PERIODO ROMANO PREPRINT [26. 11. 2010] URL: http://edoc.biblhertz.it/preprints/RJb/Sickel_Caravaggio Abstract Caravaggio’s beginnings in Rome A reconstruction of the painter’s milieu during his early Roman years There is still no precise answer to the question of when and under what circumstances the young Michelangelo Merisi moved from his Lombard home to Rome, where he is recorded for the first time only in 1597. While it is commonly assumed that he came to Rome in the Fall of 1592, the present article examines the possibility of a first, even earlier arrival in late 1591 or early 1592. The main aim of the study is, however, to outline the social settings that the young painter frequented in striving for artistic success. The reconstruction of this milieu is based on new documentary evidence. The first part regards the Roman journey of Michelangelo’s uncle, Ludovico Merisi, who lived in the Eternal city for about seven months from October 1591 to May 1592. It was very likely due to Ludovico’s connections in Rome that his nephew Michelangelo found his first lodging in the house of Pandolfo Pucci, the famous Monsignor Insalata. Pucci’s rather negative reputation, as rendered by Mancini, can now be rectified; Pucci indeed had specific interests in art. Furthermore it is possible to identify Pucci’s house situated in the Borgo in front of Saint Peter’s. In this house Caravaggio must have stayed during his first Roman journey. -

Simen-K--Nielsen---Master---2017.Pdf (7.176Mb)

The Iconic (Re)Turn: Caravaggio’s The Crucifixion of St. Peter between Image, Relic and Martyrdom in Early Modern Italy Simen K. Nielsen Master’s Thesis in the History of Art Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art, and Ideas Supervisor: Associate Professor Per Sigurd Tveitevåg Styve UNIVERSITY OF OSLO June 2017 II The Iconic (Re)Turn: Caravaggio’s The Crucifixion of St. Peter between Image, Relic and Martyrdom in Early Modern Italy III © Simen K. Nielsen 2017 The Iconic (Re)Turn: Caravaggio’s The Crucifixion of St. Peter between Image, Relic and Martyrdom in Early Modern Italy Simen K. Nielsen http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract In September 1601 Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) signed the contract to produce two paintings for the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. Modern art historiography contains millions of such details; Yet, a painting is not simply a painting, in the way history is never just history. Things, like language and words themselves, have histories. These intertwine and mesh with social, religious and cultural practices. Consequently, in order to speak about meaning in historical visual cultures, we must reconstruct and engage with these histories. Such is the aim of this thesis. In 1545, Pope Paul III Farnese called the Council of Trent, a great ecumenical endeavour which would last eighteen years, closing in December 1563. What followed was a so-called Post-Tridentine period. At a distance, these compromise what we know as the Counter-Reformation. Caravaggio grew up in the wake of these developments, when the Catholic Church, more or less finding itself in a constant state of spiritual blitzkrieg, devised a new artistic programme for its visual theology. -

Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volumes 24–25 Foreword

In the Breach of Decorum: Painting between Altar and Gallery Gail Feigenbaum Associate Director, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volumes 24–25 Foreword Dr. Susanna Pettersson Director General Associate Professor Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, (An Unpublished Drawing on Panel by Salvator (In the Breach of Decorum: Painting between is published with generous support from the Rosa Depicting a Landscape with a Philosopher Altar and Gallery, Fig. 9, p. 163). Friends of the Nationalmuseum. and Astrological Symbols, Fig. 6, p. 22). © Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY 2.0 © The Capitoline Museums, Rome. Archivio (In the Breach of Decorum: Painting between Nationalmuseum collaborates with Svenska Fotografico dei Musei Capitolini, Roma, Sovrinten- Altar and Gallery, Fig. 13, p. 167). Dagbladet, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, denza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali. © The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Grand Hôtel Stockholm, The Wineagency and (A Drawing for Pietro da Cortona’s Rape of the Sarasota. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Nationalmusei Vänner. Sabine Women, Fig. 2, p. 28). (In the Breach of Decorum: Painting between © Bibliothèque Nationale France, Paris. Altar and Gallery, Fig. 19, p. 173). Cover Illustration (The Entry of Queen Christina into Paris in 1656, © Uppsala auktionskammare, Uppsala Étienne Bouhot (1780–1862), View of the Pavillon by François Chauveau, Fig. 2, p. 32). (Acquisitions 2017: Exposé, Fig 4, p. 178). de Bellechasse on rue Saint-Dominique in Paris, © Finnish National Gallery/ Sinebrychoff Art 1823. Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 47 cm. Purchase: the Museum, Helsinki. Photo: Jaakko Lukumaa Graphic Design Hedda and N. D. Qvist Fund. -

List of Works of Art B.A

List of works of art B.A. and B.A. (Hons) History of Art B.A. and B.A. (Hons) History of Art with Fine Arts B.A. and B.A. (Hons) Fine Arts Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages The bison of Altamira, c.15,000-10,000 BC. Khafre, from Giza, c.2500BC, Egyptian Museum, Cairo Seated Scribe, from Saqqara, c. 2400 BC, Paris, Louvre. Bronze Warrior of Riace, c.450BC, Reggio Calabria Charioteer from Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, c.470BC Praxiteles, Hermes with the Young Dionysius, (Roman Copy of original of c.320BC), Archaeological Museum, Olympia Pythokritos of Rhodes (?), Nike of Samothrace, c. 190BC, Paris, Louvre The Laocoon Group, Roman Copy or original of 1st Century BC A Roman Patrician with Busts of His Ancestors, Capitoline Museum, Rome Peristyle, Palace of Diocletian, Split, Croatia Ara Pacis, Museum of the Ara Pacis, Rome Basilica of Maxentius, Rome, architecture Dura Europos (Christian House-Synagogue, Mithreum). Early Christian Paintings from the catacombs Peter and Marcellinus, Rome Sarchopagus of Junius Bassus, c.359, marble Mausoleum of Santa Costanza, Rome, architecture and mosaics Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, architecture and mosaics Baptistry of the Orthodox, Ravenna, architecture and mosaics San Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, architecture and mosaics San Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, architecture and mosaics Baptistry of the Arian, Ravenna Page 1 of 9 San Vitale, Ravenna, architecture and mosaics Throne of Maximianus, Ravenna Palace Chapel of Charlemagne, Aachen, architecture Theodulf’s oratory, Germigny des Prés, Paris Abbey Church, Corvey, Germany, architecture The Utrecht Psalter, early 9th century Ivory covers of the Lorsch, Gospels, early 9th century Gold cover of the Codex Aureus of Lindau, c.870AD Miniatures from the Moutier-Grandvalle Bible Gospel book of Otto III, Jesus washing the feet of Peter, c.1000, tempera Crucifix of Archbishop Gero, Cologne, c.