Simen-K--Nielsen---Master---2017.Pdf (7.176Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Considering Trieste Or OH, HOW I WANTED to BE YOUR BABY (But You Wouldn't Let Me)

Christoph Szalay Re-Considering Trieste or OH, HOW I WANTED TO BE YOUR BABY (but you wouldn't let me) AiR Trieste Sono lieta che a inaugurare AiR Trieste, il programma di residenze d’artista I am truly glad that it was Christoph Szalay’s residency to open the organizzato in collaborazione con MLZ Art Dep e Cultural Inventory, sia activities of AiR Trieste, the artist-in-residence program organized in stata la residenza di Christoph Szalay. collaboration with MLZ Art Dep and Cultural Inventory. The peculiar La formazione particolare di questo artista, a cavallo tra letteratura e arti background of this artist, halfway between literature and visual arts, and visive, e la sua conoscenza di contesti artistici internazionali - quello di his acquaintance with international artistic contexts - Graz, where culture Graz, dove la cultura è al centro dell’agenda politica, e quello vivacissimo is at the core of the political agenda, and the very dynamic Berlin, where di Berlino, dove Christoph ha vissuto negli ultimi anni - hanno offerto Christoph has been living in recent years - offered valuable inspirations to preziosi spunti per osservare, attraverso la lente della contemporaneità, observe, through the lens of a contemporary outlook, Trieste, a city where Trieste, una città in cui il passato riveste tanta importanza da offuscare the past takes on so great importance that it often casts shadows over the spesso il delinearsi del presente e l’emergere di visioni future. outlining of the present and the emerging of future visions. Punto di partenza del lavoro di Christoph è stato un episodio avvenuto The starting point of Christoph’s work was an event occurred in Trieste a Trieste nel 1768: la morte dello storico dell’arte Johann Joachim in 1768, the death of art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. -

Rome: a Pilgrim’S Guide to the Eternal City James L

Rome: A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Eternal City James L. Papandrea, Ph.D. Checklist of Things to See at the Sites Capitoline Museums Building 1 Pieces of the Colossal Statue of Constantine Statue of Mars Bronze She-wolf with Twins Romulus and Remus Bernini’s Head of Medusa Statue of the Emperor Commodus dressed as Hercules Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Statue Statue of Hercules Foundation of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus In the Tunnel Grave Markers, Some with Christian Symbols Tabularium Balconies with View of the Forum Building 2 Hall of the Philosophers Hall of the Emperors National Museum @ Baths of Diocletian (Therme) Early Roman Empire Wall Paintings Roman Mosaic Floors Statue of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus (main floor atrium) Ancient Coins and Jewelry (in the basement) Vatican Museums Christian Sarcophagi (Early Christian Room) Painting of the Battle at the Milvian Bridge (Constantine Room) Painting of Pope Leo meeting Attila the Hun (Raphael Rooms) Raphael’s School of Athens (Raphael Rooms) The painting Fire in the Borgo, showing old St. Peter’s (Fire Room) Sistine Chapel San Clemente In the Current Church Seams in the schola cantorum Where it was Cut to Fit the Smaller Basilica The Bishop’s Chair is Made from the Tomb Marker of a Martyr Apse Mosaic with “Tree of Life” Cross In the Scavi Fourth Century Basilica with Ninth/Tenth Century Frescos Mithraeum Alleyway between Warehouse and Public Building/Roman House Santa Croce in Gerusalemme Find the Original Fourth Century Columns (look for the seams in the bases) Altar Tomb: St. Caesarius of Arles, Presider at the Council of Orange, 529 Titulus Crucis Brick, Found in 1492 In the St. -

Hassler's Roma: a Publication That Descrive Tutte Le Meraviglie Intorno Al Nostro Al- Describes All the Marvels, Both Hidden and Not, Bergo, Nascoste E Non

HASSLER’S ROMA A CURA DI FILIPPO COSMELLI Prodotto in esclusiva per l’Hotel Hassler direzione creativa: Filippo Cosmelli direzione editoriale: Daniela Bianco fotografie: Alessandro Celani testi: Filippo Cosmelli & Giacomo Levi ricerche iconografiche: Pietro Aldobrandini traduzione: Logos Srls. - Creative services assistente: Carmen Mariel Di Buono mappe disegnate a mano: Mario Camerini progetto grafico: Leonardo Magrelli stampato presso: Varigrafica, Roma Tutti I Diritti Riservati Nessuna parte di questo libro può essere riprodotta in nessuna forma senza il preventivo permesso da parte dell’Hotel Hassler 2018. If/Books · Marchio di Proprietà di If S.r.l. Via di Parione 17, 00186 Roma · www.ifbooks.it Gentilissimi ospiti, cari amici, Dear guests, dear friends, Le strade, le piazze e i monumenti che circonda- The streets, squares and buildings that surround no l’Hotel Hassler sono senza dubbio parte inte- the Hassler Hotel are without a doubt an in- grante della nostra identità. Attraversando ogni tegral part of our identity. Crossing Trinità de mattina la piazza di Trinità de Monti, circonda- Monti every morning, surrounded by the stair- ta dalla scalinata, dal verde brillante del Pincio case, the brilliant greenery of the Pincio and the e dalla quiete di via Gregoriana, è inevitabile silence of Via Gregoriana, the desire to preser- che sorga il desiderio di preservare, e traman- ve and hand so much beauty down to future ge- dare tanta bellezza. È per questo che sono feli- nerations is inevitable. This is why I am pleased ce di presentarvi Hassler’s Roma: un volume che to present Hassler's Roma: a publication that descrive tutte le meraviglie intorno al nostro al- describes all the marvels, both hidden and not, bergo, nascoste e non. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

Renaissance Art and Architecture

Renaissance Art and Architecture from the libraries of Professor Craig Hugh Smyth late Director of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; Director, I Tatti, Florence; Ph.D., Princeton University & Professor Robert Munman Associate Professor Emeritus of the University of Illinois; Ph.D., Harvard University 2552 titles in circa 3000 physical volumes Craig Hugh Smyth Craig Hugh Smyth, 91, Dies; Renaissance Art Historian By ROJA HEYDARPOUR Published: January 1, 2007 Craig Hugh Smyth, an art historian who drew attention to the importance of conservation and the recovery of purloined art and cultural objects, died on Dec. 22 in Englewood, N.J. He was 91 and lived in Cresskill, N.J. The New York Times, 1964 Craig Hugh Smyth The cause was a heart attack, his daughter, Alexandra, said. Mr. Smyth led the first academic program in conservation in the United States in 1960 as the director of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Long before he began his academic career, he worked in the recovery of stolen art. After the defeat of Germany in World War II, Mr. Smyth was made director of the Munich Central Collecting Point, set up by the Allies for works that they retrieved. There, he received art and cultural relics confiscated by the Nazis, cared for them and tried to return them to their owners or their countries of origin. He served as a lieutenant in the United States Naval Reserve during the war, and the art job was part of his military service. Upon returning from Germany in 1946, he lectured at the Frick Collection and, in 1949, was awarded a Fulbright research fellowship, which took him to Florence, Italy. -

View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

PRESENT IN THE PERFORMANCE: STEFANO MADERNO’S SANTA CECILIA AND THE FRAME OF THE JUBILEE OF 1600 by KELLY ANNE WHITFORD A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kelly Anne Whitford Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Dr. James Harper Chairperson Dr. Nicola Camerlenghi Member Dr. Jessica Maier Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2011 ii © 2011 Kelly Anne Whitford iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kelly Anne Whitford Master of Arts Department of Art History December 2011 Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 In 1599, in commemoration of the remarkable discovery of the incorrupt remains of the early Christian martyr St. Cecilia, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrato commissioned Stefano Maderno to create a memorial sculpture which dramatically departed from earlier and contemporary monuments. While previous scholars have considered the influence of the historical setting on the conception of Maderno’s Santa Cecilia, none have studied how this historical moment affected the beholder of the work. In 1600, the Church’s Holy Year of Jubilee drew hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to Rome to take part in Church rites and rituals. -

Inter Cultural Studies of Architecture (ICSA) in Rome 2019

Intercultural Understanding, 2019, volume 9, pages 30-38 Inter Cultural Studies of Architecture (ICSA) in Rome 2019 A general exchange agreement between Mukogawa Women’s University (MWU) and Bahçeúehir㻌 University (BAU) was signed㻌 on December 8, 2008. According to this agreement, 11 Japanese second-year master’s degree students majoring in architecture visited Italy from February 19, 2019, to March 2, 2019. The purpose of “Intercultural Studies of Architecture (ICSA) in Rome” program is to gain a deeper understanding of western architecture and art. Italy is a country well known for its extensive cultural heritage and architecture. Many of the western world’s construction techniques are based, on Italy’s heritage and architecture. Therefore, Italy was selected as the most appropriate destination for this program. Based on Italy’s historic background, the students were able to investigate the structure, construction methods, spatial composition, architectural style, artistic desires based on social conditions, and design intentions of architects and artists for various buildings. This year’s program focused on “ancient Roman architecture and sculpture,” “early Christian architecture,” “Renaissance architecture, sculpture, and garden,” and “Baroque architecture and sculpture. ” Before the ICSA trip to Rome, the students attended seminars on studying historic places during their visit abroad and were asked to make a presentation about the stuff that they learned during these seminars. During their trip to Rome, the students had the opportunity to deepen their understanding of architecture and art, measure the height and span of architecture, and draw sketches and make presentations related to some sites that they have visited. A report describing the details of this program is given below. -

Santa Maria Del Popolo Piazza Del Popolo Metro Station: Flaminio, Line a 7 AM – 12 PM (Closed Sunday) 4 PM – 7 PM (Closed Sunday)

Santa Maria del Popolo Piazza del Popolo Metro station: Flaminio, line A 7 AM – 12 PM (Closed Sunday) 4 PM – 7 PM (Closed Sunday) Sculpture of Habakkuk and the Angel by Bernini (after 1652) in the Chigi Chapel Crucifixion of St. Peter (1600-01) by Caravaggio in the Cerasi Chapel. Baroque facade added by Bernini in 1600 Standing on the Piazza del Popolo, near the northern gate of the Aurelian Wall, the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo is a small temple with a splendid Renaissance decoration in its interior. In its interior Santa Maria del Popolo’s decoration is unlike any other church in Rome. The ceiling, less high than most built during the same period, is practically bare, while the decoration of each of the small chapels is especially remarkable. Among the beautiful art work found in the church, it is worth highlighting the Chapel Cerasi, which houses two canvases by Caravaggio from 1600, and the Chapel Chigi, built and decorated by Raphael. If you look closely at the wooden benches, you’ll be able to see inscriptions with the names of the people the benches are dedicated to. This custom is also found in a lot of English speaking countries like Scotland or Edinburgh, where the families of the person deceased buy urban furniture in their honour. ******************************************** Located next to the northern gate of Rome on the elegant Piazza del Popolo, the 15th-century Santa Maria del Popolo is famed for its wealth of Renaissance art. Its walls and ceilings are decorated with paintings by some of the greatest artists ever to work in Rome: Pinturicchio, Raphael, Carracci, Caravaggio and Bernini. -

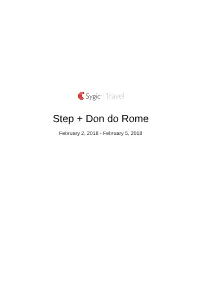

Step + Don Do Rome

Step + Don do Rome February 2, 2018 - February 5, 2018 Friday ColosseumB8 • Piazza del Colosseo, 00184 February 2, 2018 Rome Ciampino Airport F11 • Roma Ciampino Airport (Giovan Battista Pastine Airport), Via Appia Nuova B&B La Terrazza sul Colosseo 1651, 00040 Rome Ciampino, Italy B9 • Via Ruggero Bonghi 13/b, 00184 Rome Basilica of Saint Mary Major B9 • Piazza di S. Maria Maggiore, 42, 00100 Roma RM, Italy Palazzo delle Esposizioni B8 • Via Nazionale 194, Rome, Latium, 00184, Italy Church of St Andrea della Valle B8 • Corso del Rinascimento Rome, Italy 00186 Trevi Fountain B8 • Piazza di Trevi, 00187 Roma, Italy Caffè Tazza d'Oro B8 • 84 Via degli Orfani, 00186 Pantheon B8 • Piazza della Rotonda, 00186 Roma, Italy Freni e Frizioni B8 • Rome Trastevere B8 • Rome Area sacra dell'Argentina B8 • Rome Venice Square B8 • Rome Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II B8 • Piazza Venezia, 00187 Roma, Italy Trajan's Column B8 • Via dei Fori Imperiali, Roma, Italy Imperial Forums B8 • Largo della Salara Vecchia 5/6, 9 00184 Roma, Italy Forum of Augustus B8 • Via dei Fori Imperiali, Rome, Latium, 00186, Italy Forum of Trajan B8 • Via IV Novembre 94, 00187 Roma, Italy Saturday Sunday February 3, 2018 February 4, 2018 B&B La Terrazza sul Colosseo B&B La Terrazza sul Colosseo B9 • Via Ruggero Bonghi 13/b, 00184 Rome B9 • Via Ruggero Bonghi 13/b, 00184 Rome Colosseum Navona Square B8 • Piazza del Colosseo, 00184 B8 • Piazza Navona, 00186 Rome, Italy Imperial Forums Pantheon B8 • Largo della Salara Vecchia 5/6, 9 00184 Roma, Italy B8 • Piazza della Rotonda, -

Caravaggio's Capitoline Saint John

Caravaggio’s Capitoline Saint John: An Emblematic Image of Divine Love Shannon Pritchard With an oeuvre filled with striking, even shocking works, mid-1601 on the invitation of the Roman Marchese Ciriaco Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Saint John the Baptist Mattei and his two brothers, Cardinal Girolamo Mattei and in the Wilderness, still remains one of his most visually com- Asdrubale Mattei, and remained there for approximately two pelling works (Figure 1).1 The painting, now in the Capitoline years.4 Thirteen years later, his painting was recorded in the Museum in Rome, was completed around 1601-02 during the 1616 inventory of Ciriaco’s only son and heir, Giovanni Battista height of the artist’s Roman career.2 At first glance, the nude Mattei, at which time it was listed as “Saint John the Baptist figure, splayed from corner to corner across the entire canvas, with his lamb by the hand of Caravaggio.”5 From this point produces an uneasy response in the viewer. The boy’s soft, forward, the painting is documented in numerous invento- curly hair, prepubescent body and coquettish turn of the head ries, and these records reveal that uncertainty over the subject endow the image with an unexpected sensuality. It is precisely matter was present virtually from the beginning. In 1623, this quality that has spawned nearly four hundred years of Giovanni Battista Mattei bequeathed the painting to Cardinal debate about the identity of Caravaggio’s nude youth, the sup- Francesco Maria del Monte, in whose 1627 inventory it was posed John the Baptist.