The Syntax of Chaldean Neo-Aramaic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Personal Name Here Is Again Obscure. At

342 THE FIRST ARAMAIC INSCRIPTION FROM INDIA 1. 10 : " his conduct " ? 1. 11 : " and also his sons." 1. 12 : the personal name here is again obscure. At the end of the line are traces of the right-hand side of a letter, which might be samekh or beth; if we accept the former, it is possible to vocalize as Pavira-ram, i.e. Pavira-rdja, corresponding to the Sanskrit Pravira- rdja. The name Pravira is well known in epos, and might well be borne by a real man ; and the change of a sonant to a surd consonant, such as that of j to «, is quite common in the North-West dialects. L. D. BARNETT. THE FIRST ARAMAIC INSCRIPTION FROM INDIA I must thank Mr. F. W. Thomas for his great kindness in sending me the photograph taken by Sir J. H. Marshall, and also Dr. Barnett for letting me see his tracing and transliteration. The facsimile is made from the photo- graph, which is as good as it can be. Unfortunately, on the original, the letters are as white as the rest of the marble, and it was necessary to darken them in order to obtain a photograph. This process inti'oduces an element of uncertainty, since in some cases part of a line may have escaped, and in others an accidental scratch may appear as part of a letter. Hence the following passages are more or less doubtful: line 4, 3PI; 1. 6, Tpfl; 1. 8, "123 and y\; 1. 9, the seventh and ninth letters; 1. 10, ID; 1. -

History of Writing

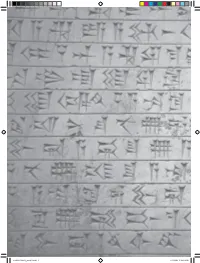

History of Writing On present archaeological evidence, full writing appeared in Mesopotamia and Egypt around the same time, in the century or so before 3000 BC. It is probable that it started slightly earlier in Mesopotamia, given the date of the earliest proto-writing on clay tablets from Uruk, circa 3300 BC, and the much longer history of urban development in Mesopotamia compared to the Nile Valley of Egypt. However we cannot be sure about the date of the earliest known Egyptian historical inscription, a monumental slate palette of King Narmer, on which his name is written in two hieroglyphs showing a fish and a chisel. Narmer’s date is insecure, but probably falls in the period 3150 to 3050 BC. In China, full writing first appears on the so-called ‘oracle bones’ of the Shang civilization, found about a century ago at Anyang in north China, dated to 1200 BC. Many of their signs bear an undoubted resemblance to modern Chinese characters, and it is a fairly straightforward task for scholars to read them. However, there are much older signs on the pottery of the Yangshao culture, dating from 5000 to 4000 BC, which may conceivably be precursors of an older form of full Chinese writing, still to be discovered; many areas of China have yet to be archaeologically excavated. In Europe, the oldest full writing is the Linear A script found in Crete in 1900. Linear A dates from about 1750 BC. Although it is undeciphered, its signs closely resemble the somewhat younger, deciphered Linear B script, which is known to be full writing; Linear B was used to write an archaic form of the Greek language. -

Communicator Summer 2015 47

Learn more about Microsoft Word Start to delve into VBA and create your own macros CommunicatorThe Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators Summer 2015 What’s a technical metaphor? Find out more. Create and implement personalised learning Re-think your accessibility requirements with SVG Discover how a security technology team engaged with customers 46 Global brand success Success with desktop publishing Kavita Kovvali from translate plus takes a look into the role that DTP plays to help organisations maximise their international reach. them, with negative implications for a brand if it’s not. Common Sense Advisory’s survey across three continents about online buying behaviour states that 52% of participants only make online purchases if a website presents information in their language, with many considering this more important than the price of the product.2 Supporting this is an analytical report carried out by the European Commission across 27 EU member states regarding purchasing behaviour. Their survey shows that of their respondents, 9 out of 10 internet users3 said that when given a choice of languages, they always visited a website in their own language, with only a small majority (53%) stating that they would accept using an English language site if their own language wasn’t available. This shows the overwhelming need to communicate to audiences in their local languages. As you can see in this chart4 compiled by Statista, although English has the highest number of total speakers due to its widespread learning across the word, other languages such as Chinese and Hindi have a higher number of native speakers. -

Learn-The-Aramaic-Alphabet-Ashuri

Learn The ARAMAIC Alphabet 'Hebrew' Ashuri Script By Ewan MacLeod, B.Sc. Hons, M.Sc. 2 LEARN THE ARAMAIC ALPHABET – 'HEBREW' ASHURI SCRIPT Ewan MacLeod is the creator of the following websites: JesusSpokeAramaic.com JesusSpokeAramaicBook.com BibleManuscriptSociety.com Copyright © Ewan MacLeod, JesusSpokeAramaic.com, 2015. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into, a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, scanning, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission from the copyright holder. The right of Ewan MacLeod to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the copyright holder's prior consent, in any form, or binding, or cover, other than that in which it is published, and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Jesus Spoke AramaicTM is a Trademark. 3 Table of Contents Introduction To These Lessons.............................................................5 How Difficult Is Aramaic To Learn?........................................................7 Introduction To The Aramaic Alphabet And Scripts.............................11 How To Write The Aramaic Letters....................................................... 19 -

Introduction to Syriac: an Elementary Grammar with Readings From

INTRODUCTION TO SYRIAC An Elementary Grammar with Readings from Syriac Literature Wheeler M. Thackston IBEX Publishers Bethesda, Maryland Introduction to Syriac An Elementary Grammar with Readings from Syriac Literature by Wheeler M. Thackston Copyright © 1999 Ibex Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any manner whatsoever, except in the form of a review, without written permission from the publisher. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Services—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 IBEX Publishers Post Office Box 30087 Bethesda, Maryland 20824 U.S.A. Telephone: 301-718-8188 Facsimile: 301-907-8707 www.ibexpub.com LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Thackston, W.M. (Wheeler Mcintosh), 1944- Introduction to Syriac : an elementary grammar with readings from Syriac literature / by W. M. Thackston. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-936347-98-8 1. Syriac language —Grammar. I. Title. PJ5423T53 1999 492'.382421~dc21 99-39576 CIP Contents PREFACE vii PRELIMINARY MATTERS I. The Sounds of Syriac: Consonants and Vowels x II. Begadkepat and the Schwa xii III. Syllabification xiv IV. Stress xv V. Vocalic Reduction and Prosthesis xv VI. The Syriac Alphabet xvii VII. Other Orthographic Devices xxi VIII. Alphabetic Numerals xxiii IX. Comparative Chart of Semitic Consonants xxiv X. Preliminary Exercise xxvi -

Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. & Dr. K. Muniratnam Director i/c, Epigraphy, ASI, Mysore Dr. Sayantani Pal Dept. of AIHC, University of Calcutta. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Indian Epigraphy Module Name/Title Kharosthi Script Module Id IC / IEP / 15 Pre requisites Kharosthi Script – Characteristics – Origin – Objectives Different Theories – Distribution and its End Keywords E-text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction Kharosthi was one of the major scripts of the Indian subcontinent in the early period. In the list of 64 scripts occurring in the Lalitavistara (3rd century CE), a text in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, Kharosthi comes second after Brahmi. Thus both of them were considered to be two major scripts of the Indian subcontinent. Both Kharosthi and Brahmi are first encountered in the edicts of Asoka in the 3rd century BCE. 2. Discovery of the script and its Decipherment The script was first discovered on one side of a large number of coins bearing Greek legends on the other side from the north western part of the Indian subcontinent in the first quarter of the 19th century. Later in 1830 to 1834 two full inscriptions of the time of Kanishka bearing the same script were found at Manikiyala in Pakistan. After this discovery James Prinsep named the script as ‘Bactrian Pehelevi’ since it occurred on a number of so called ‘Bactrian’ coins. To James Prinsep the characters first looked similar to Pahlavi (Semitic) characters. -

THE ARAMAIC of the ZOHAR These Course Handouts Are Also The

The Aramaic Language of the Zohar I * Fall 2011 * Justin Jaron Lewis THE ARAMAIC OF THE ZOHAR These course handouts are also the first draft of a textbook. As you read them or work through them, please let the author know of any mistakes, anything that doesn’t work well for you in your language study, and any suggestions for improvements! _____________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Purpose of this Course The purpose of this course is to give you a reading knowledge of the Aramaic language of the Zohar. By the end of the course you should be able to read passages of the Zohar in the original, if not without the help of a translation, then at least without depending on the translation blindly. The particular dialect of Aramaic used in the Zohar does not exist as a spoken language and perhaps never did, and we are aiming for a reading knowledge only. This means that you will be spared many of the typical challenges of language study, such as mastering correct pronunciation or being able to express yourself in conversation. This, and the fact that the Zohar’s core vocabulary is quite small, should make this easy as language courses go. Nevertheless, just as with any language study, you’ll want to immerse yourself in the language as much as possible, working hard and, most importantly, steadily, in order to achieve fluency — in this case the ability to read the Zohar fluently. Background The Zohar, which first began to circulate in manuscript in late thirteenth-century Spain, is the central text of Kabbalah, a largely esoteric but very influential tradition which encompasses distinct approaches to theology, spiritual practice, etc. -

Imperial Aramaic

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3273R2 L2/07-197R2 2007-07-25 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Preliminary proposal for encoding the Imperial Aramaic script in the SMP of the UCS Source: Michael Everson Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2007-07-25 1. Background. The Imperial Aramaic script is the head of a rather complex family of scripts. It is named from the use of Aramaic as the language of regional and supraregional correspondance in the Persian Empire though, in fact, the language was in use in this function already before that. The practice continued after the demise of the Persian Empire and was the starting-point for the writing-systems of most of the Middle Iranian languages, namely Inscriptional Parthian, Inscriptional Pahlavi, Psalter Pahlavi, Book Pahlavi, and Avestan. Imperial Aramaic has many other descendents, including Mongolian and possibly Brahmi. The term, “Imperial Aramaic”, refers both to a script and to a language. As a script term, Imperial Aramaic refers to the writing system in use in the Neo-Assyrian and Persian Empires, and was used to write Aramaic, but also other languages. There is no script code for Imperial Aramaic yet registered by ISO 15924. As a language term, Imperial Aramaic refers to a historic variety of Aramaic, as spoken and written during the period roughly from 600 BCE to 200 BCE. The Imperial Aramaic language has been given the ISO 639 language code in “arc”. -

Writing Systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson

9780198606536_essay01.indd 2 8/17/2009 2:19:03 PM writing systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson 1 The emergence of writing 2 Development and diffusion of writing systems 3 Decipherment 4 Classification of writing systems 5 The origin of the alphabet 6 The family of alphabets 7 Chinese and Japanese writing 8 Electronic writing 1 The emergence of writing istrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many Without writing, there would be no recording, no regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, history, and of course no books. The creation of writ- rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly ing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more for example, the world would be virtually unaware of complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 in three *scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional sym- alphabetic. bols in clay for these three-dimensional tokens was a How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, first step towards writing, according to this theory. -

Neo-Aramaic Garshuni: Observations Based on Manuscripts

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 17.1, 17-31 © 2014 by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press NEO-ARAMAIC GARSHUNI: OBSERVATIONS BASED ON MANUSCRIPTS EMANUELA BRAIDA UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO* ABSTRACT The present paper is a preliminary study of key spelling features detected in the rendering of foreign words in some Neo-Aramaic Christian texts belonging to the late literary production from the region of Alqosh in Northern Iraq. This Neo-Syriac literature laid the groundwork for its written form as early as the end of the 16th century, when scribes of the so-called ‘school of Alqosh’ wrote down texts for the local population. From a linguistic point of view, scribes and authors developed a Neo-Syriac literary koine based on the vernacular languages of the region of Alqosh. Despite the sporadic presence of certain orthographical conventions, largely influenced by Classical Syriac, these texts lacked a standard orthography and strict conventions in spelling. Since a large number of vernacular terms have strayed over time from the classical language or, in many cases, they have been borrowed from other languages, the rendering of the terms was usually characterized by a mostly phonetic rendition, especially in the case of foreign words that cannot be written according to an original or a standard form. In these cases, scribes and authors had to adapt the Syriac alphabet to * A Post Doctoral Research Fellowship granted by Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Amir Harrak, for the guidance, encouragement and advice he has provided throughout my time as Post-doctoral fellow. -

INTRODUCTION Nabatean Or Syriac?

Chapter I INTRODUCTION Among the family of scripts descending Nabatean or Syriac? from the Phoenician alphabet, Arabic seems to be the most remote from its ancestor. Not In 1865 Theodor Noldeke related the only have the rectilinear characters changed to origin of Ku.fie script to Nabatean.2 Very soon integrated curves and loops, but also the letter thereafter numerous scholars, including M. A. groups have been transformed from a row of Levy, M. de Vogue, J. Karabacek and J. disconnected signs to an organic band. As a Euting, joined him in this opinion, leading to a result, the individual letters, which once general consensus. Half a century later, J. occupied isolated oblong spaces, now grow Starcky, who had originally held the same out of (and return to) a connecting line. The view, adopted another approach: the theory diversity of heights and sizes among the that Arabic has its roots in a Syriac cursive. In different letters has increased, as has the his article Petra et la Nabatene, 3 he number of their positional variants. Although questioned the affiliation of Nabatean and the individual Arabic graphemes can be traced Arabic scripts on the following grounds: the without difficulty to the Aramaic alphabet, the relationship, he claims, had been elaborated drastic change in their graphic character and on the basis of unreliable facsimiles, or of rare spatial arrangement, i.e., the ductus, has or obscure letter forms that failed to display fueled a controversy: which specific Aramaic the general characteristics of the late Nabatean branch is responsible for the script transfer, ducrus. -

A Note on the Phonetic and Graphic Representation of Greek Vowels and of the Spiritus Asper in the Aramaic Transcription of Greek Loanwords Abraham Wasserstein

A Note on the Phonetic and Graphic Representation of Greek Vowels and of the Spiritus Asper in the Aramaic Transcription of Greek Loanwords Abraham Wasserstein Raanana Meridor has probably taught Greek to more men and women in Israel than any other person. Her learning, constantly enriched by intellectual curiosity, enthusiasm and conscientiousness, has for many years been a source of encour- agement to her students and a model to be emulated by her colleagues. It is an honour to be allowed to participate in the tribute offered to her on her retirement by those who are linked to her by friendship, affection and admiration. Ancient transcriptions of Greek (and other) names and loanwords into Semitic alphabets are a notorious source of mistakes and ambiguities. Since these alpha- bets normally use only consonantal signs the vowels of the words in the source language are often liable to be corrupted. This happens routinely in Greek loan- words in Syriac and in rabbinic Hebrew and Aramaic. Thus, though no educated in rabbinic Hebrew being סנהדרין modern Hebrew-speaker has any doubt about derived from the Greek συνέδριον, there cannot have been many occasions since late antiquity on which any non-hellenized Jew has pronounced the first vowel of that word in any way other than if it had been an alpha; indeed I know of no modern western language in which that word, when applied to the Pales- tinian institution of that name is not, normally, = Sanhedrin.1 Though, in principle, it can be stated that practically all vowel sounds can remain unrepresented in Syriac and Jewish Aramaic transcription2 it is true that it is possible to indicate Greek vowels or diphthongs by approximate representa- See below for the internal aspiration in this word.