THE ARAMAIC of the ZOHAR These Course Handouts Are Also The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Personal Name Here Is Again Obscure. At

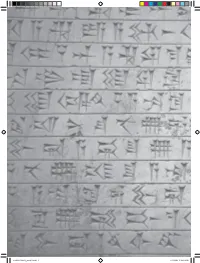

342 THE FIRST ARAMAIC INSCRIPTION FROM INDIA 1. 10 : " his conduct " ? 1. 11 : " and also his sons." 1. 12 : the personal name here is again obscure. At the end of the line are traces of the right-hand side of a letter, which might be samekh or beth; if we accept the former, it is possible to vocalize as Pavira-ram, i.e. Pavira-rdja, corresponding to the Sanskrit Pravira- rdja. The name Pravira is well known in epos, and might well be borne by a real man ; and the change of a sonant to a surd consonant, such as that of j to «, is quite common in the North-West dialects. L. D. BARNETT. THE FIRST ARAMAIC INSCRIPTION FROM INDIA I must thank Mr. F. W. Thomas for his great kindness in sending me the photograph taken by Sir J. H. Marshall, and also Dr. Barnett for letting me see his tracing and transliteration. The facsimile is made from the photo- graph, which is as good as it can be. Unfortunately, on the original, the letters are as white as the rest of the marble, and it was necessary to darken them in order to obtain a photograph. This process inti'oduces an element of uncertainty, since in some cases part of a line may have escaped, and in others an accidental scratch may appear as part of a letter. Hence the following passages are more or less doubtful: line 4, 3PI; 1. 6, Tpfl; 1. 8, "123 and y\; 1. 9, the seventh and ninth letters; 1. 10, ID; 1. -

History of Writing

History of Writing On present archaeological evidence, full writing appeared in Mesopotamia and Egypt around the same time, in the century or so before 3000 BC. It is probable that it started slightly earlier in Mesopotamia, given the date of the earliest proto-writing on clay tablets from Uruk, circa 3300 BC, and the much longer history of urban development in Mesopotamia compared to the Nile Valley of Egypt. However we cannot be sure about the date of the earliest known Egyptian historical inscription, a monumental slate palette of King Narmer, on which his name is written in two hieroglyphs showing a fish and a chisel. Narmer’s date is insecure, but probably falls in the period 3150 to 3050 BC. In China, full writing first appears on the so-called ‘oracle bones’ of the Shang civilization, found about a century ago at Anyang in north China, dated to 1200 BC. Many of their signs bear an undoubted resemblance to modern Chinese characters, and it is a fairly straightforward task for scholars to read them. However, there are much older signs on the pottery of the Yangshao culture, dating from 5000 to 4000 BC, which may conceivably be precursors of an older form of full Chinese writing, still to be discovered; many areas of China have yet to be archaeologically excavated. In Europe, the oldest full writing is the Linear A script found in Crete in 1900. Linear A dates from about 1750 BC. Although it is undeciphered, its signs closely resemble the somewhat younger, deciphered Linear B script, which is known to be full writing; Linear B was used to write an archaic form of the Greek language. -

Learn-The-Aramaic-Alphabet-Ashuri

Learn The ARAMAIC Alphabet 'Hebrew' Ashuri Script By Ewan MacLeod, B.Sc. Hons, M.Sc. 2 LEARN THE ARAMAIC ALPHABET – 'HEBREW' ASHURI SCRIPT Ewan MacLeod is the creator of the following websites: JesusSpokeAramaic.com JesusSpokeAramaicBook.com BibleManuscriptSociety.com Copyright © Ewan MacLeod, JesusSpokeAramaic.com, 2015. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into, a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, scanning, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission from the copyright holder. The right of Ewan MacLeod to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the copyright holder's prior consent, in any form, or binding, or cover, other than that in which it is published, and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Jesus Spoke AramaicTM is a Trademark. 3 Table of Contents Introduction To These Lessons.............................................................5 How Difficult Is Aramaic To Learn?........................................................7 Introduction To The Aramaic Alphabet And Scripts.............................11 How To Write The Aramaic Letters....................................................... 19 -

Introduction to Syriac: an Elementary Grammar with Readings From

INTRODUCTION TO SYRIAC An Elementary Grammar with Readings from Syriac Literature Wheeler M. Thackston IBEX Publishers Bethesda, Maryland Introduction to Syriac An Elementary Grammar with Readings from Syriac Literature by Wheeler M. Thackston Copyright © 1999 Ibex Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any manner whatsoever, except in the form of a review, without written permission from the publisher. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Services—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 IBEX Publishers Post Office Box 30087 Bethesda, Maryland 20824 U.S.A. Telephone: 301-718-8188 Facsimile: 301-907-8707 www.ibexpub.com LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Thackston, W.M. (Wheeler Mcintosh), 1944- Introduction to Syriac : an elementary grammar with readings from Syriac literature / by W. M. Thackston. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-936347-98-8 1. Syriac language —Grammar. I. Title. PJ5423T53 1999 492'.382421~dc21 99-39576 CIP Contents PREFACE vii PRELIMINARY MATTERS I. The Sounds of Syriac: Consonants and Vowels x II. Begadkepat and the Schwa xii III. Syllabification xiv IV. Stress xv V. Vocalic Reduction and Prosthesis xv VI. The Syriac Alphabet xvii VII. Other Orthographic Devices xxi VIII. Alphabetic Numerals xxiii IX. Comparative Chart of Semitic Consonants xxiv X. Preliminary Exercise xxvi -

Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. & Dr. K. Muniratnam Director i/c, Epigraphy, ASI, Mysore Dr. Sayantani Pal Dept. of AIHC, University of Calcutta. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Indian Epigraphy Module Name/Title Kharosthi Script Module Id IC / IEP / 15 Pre requisites Kharosthi Script – Characteristics – Origin – Objectives Different Theories – Distribution and its End Keywords E-text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction Kharosthi was one of the major scripts of the Indian subcontinent in the early period. In the list of 64 scripts occurring in the Lalitavistara (3rd century CE), a text in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, Kharosthi comes second after Brahmi. Thus both of them were considered to be two major scripts of the Indian subcontinent. Both Kharosthi and Brahmi are first encountered in the edicts of Asoka in the 3rd century BCE. 2. Discovery of the script and its Decipherment The script was first discovered on one side of a large number of coins bearing Greek legends on the other side from the north western part of the Indian subcontinent in the first quarter of the 19th century. Later in 1830 to 1834 two full inscriptions of the time of Kanishka bearing the same script were found at Manikiyala in Pakistan. After this discovery James Prinsep named the script as ‘Bactrian Pehelevi’ since it occurred on a number of so called ‘Bactrian’ coins. To James Prinsep the characters first looked similar to Pahlavi (Semitic) characters. -

Imperial Aramaic

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3273R2 L2/07-197R2 2007-07-25 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Preliminary proposal for encoding the Imperial Aramaic script in the SMP of the UCS Source: Michael Everson Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2007-07-25 1. Background. The Imperial Aramaic script is the head of a rather complex family of scripts. It is named from the use of Aramaic as the language of regional and supraregional correspondance in the Persian Empire though, in fact, the language was in use in this function already before that. The practice continued after the demise of the Persian Empire and was the starting-point for the writing-systems of most of the Middle Iranian languages, namely Inscriptional Parthian, Inscriptional Pahlavi, Psalter Pahlavi, Book Pahlavi, and Avestan. Imperial Aramaic has many other descendents, including Mongolian and possibly Brahmi. The term, “Imperial Aramaic”, refers both to a script and to a language. As a script term, Imperial Aramaic refers to the writing system in use in the Neo-Assyrian and Persian Empires, and was used to write Aramaic, but also other languages. There is no script code for Imperial Aramaic yet registered by ISO 15924. As a language term, Imperial Aramaic refers to a historic variety of Aramaic, as spoken and written during the period roughly from 600 BCE to 200 BCE. The Imperial Aramaic language has been given the ISO 639 language code in “arc”. -

Writing Systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson

9780198606536_essay01.indd 2 8/17/2009 2:19:03 PM writing systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson 1 The emergence of writing 2 Development and diffusion of writing systems 3 Decipherment 4 Classification of writing systems 5 The origin of the alphabet 6 The family of alphabets 7 Chinese and Japanese writing 8 Electronic writing 1 The emergence of writing istrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many Without writing, there would be no recording, no regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, history, and of course no books. The creation of writ- rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly ing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more for example, the world would be virtually unaware of complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 in three *scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional sym- alphabetic. bols in clay for these three-dimensional tokens was a How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, first step towards writing, according to this theory. -

INTRODUCTION Nabatean Or Syriac?

Chapter I INTRODUCTION Among the family of scripts descending Nabatean or Syriac? from the Phoenician alphabet, Arabic seems to be the most remote from its ancestor. Not In 1865 Theodor Noldeke related the only have the rectilinear characters changed to origin of Ku.fie script to Nabatean.2 Very soon integrated curves and loops, but also the letter thereafter numerous scholars, including M. A. groups have been transformed from a row of Levy, M. de Vogue, J. Karabacek and J. disconnected signs to an organic band. As a Euting, joined him in this opinion, leading to a result, the individual letters, which once general consensus. Half a century later, J. occupied isolated oblong spaces, now grow Starcky, who had originally held the same out of (and return to) a connecting line. The view, adopted another approach: the theory diversity of heights and sizes among the that Arabic has its roots in a Syriac cursive. In different letters has increased, as has the his article Petra et la Nabatene, 3 he number of their positional variants. Although questioned the affiliation of Nabatean and the individual Arabic graphemes can be traced Arabic scripts on the following grounds: the without difficulty to the Aramaic alphabet, the relationship, he claims, had been elaborated drastic change in their graphic character and on the basis of unreliable facsimiles, or of rare spatial arrangement, i.e., the ductus, has or obscure letter forms that failed to display fueled a controversy: which specific Aramaic the general characteristics of the late Nabatean branch is responsible for the script transfer, ducrus. -

WRITING SYSTEMS Tjeerd TICHELAAR

WRITING SYSTEMS Tjeerd TICHELAAR Meaning, sound and looks during the manifold changes of sovereignty between the new national states of 19th and 20th century Eastern and Geographical names, as all names, can be viewed from South-Eastern Europe: examples are Austrian Karlsbad three different aspects: semantic, phonetic and graphic. changing into Czech Karlovy Vary, Hungarian Újvidék Semantically, names carry a meaning at the time they are becoming Croat Novi Sad. An example outside Europe, coined. Because of its meaning as ‘ford on the Roman but equally associated with the emergence of national road’, there could, at least to local people, be no misun- sentiments, is the translation of Spanish Casablanca derstanding about the location of the settlement named (itself a translation of Portuguese Casa Branca – the Por- Stratford. The meaning may be lost in the course of time, tuguese founded the place in 1515) into Arabic ad-Dar al- either because the language the name springs from is no Bayda’. In other cases, name changes following transfer longer current, or because the name itself degenerates to of ownership explicitly reflect a change in the meaning such an extent that its meaning can no longer be recog- the object has to the new owner compared to the one nized. More often, the original meaning ceases to be attached to it by his predecessor. The seaport city of appropriate. The Greek settlement named Neapolis or Reval was just a ‘little sand bank’ to its Danish founders ‘New Town’ by its founders, to set it apart from the ‘old in 1219. Although it successively passed into Teutonic town’ they had fled (neighbouring Kymai, that had been (1346), Swedish (1561), and Russian hands (1710), it established six or seven generations earlier by colonists was allowed to retain its name; but upon the emergence from the Ionian city state of Chalcis), retained its Greek of the independent Estonian nation-state in 1917, the name as it was incorporated in the Roman republic in the town now chosen to be the nation’s capital reverted to a 4th century BC. -

The Alphabet

The Alphabet Alan Millard 1. Writing in Canaan 1.1. Egyptian and Babylonian When Israelites occupied Canaan at the end of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1250–1150 bce), they took over a land where writing had been known for almost two thousand years. In the south, potsherds bearing Egyptian hieroglyphs for the name of pharaoh Narmer have been found at Arad and Tell el-ʿAreini, while seal impressions with names of other early pharaohs and officials were discovered atʿ En Besor. Those signs of authority were recognized in Early Bronze Age Canaan (ca. 3500–2200 bce), whether or not local people could read them. Although Babylonian cuneiform was current in Syria during the latter part of the third millennium bce, the earliest cuneiform texts found in Canaan belong to the Old Babylonian period or Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000–1550). They are seven incomplete tablets and two liver models, which imply a local readership, and part of an inscribed stone jar, all from Hazor; perhaps a letter from Shechem; an administrative text from Hebron; and a fragment from Gezer (the dating of the last three between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, ca. 2000– 1200, is debatable). The few inscribed cylinder seals did not originate in Canaan, and their legends were not necessarily read there. At the same time, numerous Egyptian scarabs circulated, many bearing the names of officials often with funerary formulas, but they functioned principally as amulets, so their legends were not necessarily more meaningful than magic signs. Egyptian and Babylonian writing are better attested from the Late Bronze Age (ca. -

The Aramaic Alphabet the Aramaic and Hebrew Alphabets Are the Same

Chapter Two The Aramaic Alphabet The Aramaic and Hebrew alphabets are the same. Letter Final form Name Transliteration1 Pronunciation a @la Yalĕf Y silent B tyb bêt b ball b bêt v (b) vine G lmyg gimĕl g gift g gimĕl gh (g) ghost D tlD dalĕt d debt d dalĕt th (d) the h ah hē’ h his w ww vāv (or wāw)2 v or w vine or way z !yz zāyĭn z Zion x tyx I hêt ch ( h ̣) Bach j tyj I têt t ( t ̣) tall y dwy yôd y yes K & @k kăf k king k $ kăf ch (k) peach l dml lāmĕd l lion m ~ ~m mēm m man n ! !wn nûn n no s $ms sāmĕk s sin [ !y[ ‘ăyĭn ‘ silent P @ aP pē’ p pet p @ pē’ ph (or f) fat c # ydc tsādê ts ( s ̣) nets q @wq qôf q king r vyr rêš r run f !yf sîn s sin v !yv shîn sh (š) shine T wT tāv (tāw) t toy t tāv (tāw) th (t) throne 1 Transliteration is the process of assigning an English equivalent to the Hebrew letter. 2 I prefer vav over waw. That is how I learned it so I will continue with that heritage. Notice the five groupings. These are organized in four or five letters per group in order to help in the memorization process. It is far easier to memorize a group of four or five letters, then, once the group is memorized, move on to the next group. -

The Syntax of Chaldean Neo-Aramaic

Florida Atlantic University Undergraduate Research Journal THE SYNTAX OF CHALDEAN NEO-ARAMAIC Catrin Seepo & Michael Hamilton Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters 1. Introduction and the Canaanite branches of Northwest Semitic was relatively recent” (p.6). When the big empires, such as Chaldean Neo-Aramaic is a Semitic language Babylonian, Assyrian, and Persian, used Aramaic as spoken by the Chaldean Christians in Iraq and around their official language, which marked the next period of the world. There are many dialects of Chaldean Neo- Aramaic, and that is the Official, Imperial, or Standard Aramaic, and in this research, I will be examining ACNA, Literary Aramaic. After the falling of the Persian Empire, 1 which is spoken in the town of Alqosh in the Plains regional variations of Aramaic had emerged due to the of Nineveh in the northern part of Iraq. Currently, the lack of language standardization. The third period of language is in decline and is understudied. Therefore, Aramaic, Middle Aramaic, was spoken during the time of this paper attempts to preserve the ACNA by generally Jesus Christ. The time between the second and the ninth describing its syntax, and specifically determining its centuries C.E. marked ‘Late’ Aramaic. Finally, Modern word order, which typically refers to the order of subject Aramaic is currently spoken by most Christians in Iraq (S), verb (V) and object (O) in a sentence. and Syria, southeastern Turkey (near Tur Abdin), and Mandeans in southern Iran (p.6-7). 1.1 Historical Overview Modern Aramaic has various variations, one Chaldean Neo-Aramaic is a northeastern of which is Chaldean Neo-Aramaic.