Livelihood Desk Review for Pact and FANTA-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Will Lift My Weary Eyes • SATB • © 2019 HELBLING Grundsätzlich This Copyright AUSTRIA: Kaplanstrasse 9, 6063 Rum/Innsbruck | GERMANY: P.O

2 I Will I WillLift Lift My My WearyWeary Eyes Eyes Lyrics: Kinley Lange, based on Psalm 121 Music: Kinley Lange *) Freely, plaintively S 4 4 A 4 4 mf (solo or section) T 4 4 And I will lift my wear y eyes, I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the B 4 4 5 (tutti) help that I have need ed will sure ly tum ble down, I will lift my eyes un to the hills. And I will 9 G CG D mf And the mf Hm I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the lift my wear y eyes, I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the • The vowels should be very bright and open, a bit nasal in quality, and the singing should be without vibrato. Many of the upward-moving intervals, as well as certain repeated notes, should be embellished with a scoop or slight grace-note glissando from beneath. Take care not to over-do this as it is primarily a soloistic embellishment and could easily become overbearing in choral singing. • The piece can be performed with traditional Blue Grass instruments. If so, it is recommended that a bass not be used as it could be in conflict with the sung bass line. Mandolin, violin and guitar will work nicely, following the indicated chords. *) Optional fiddle drone accompaniment til bar 8 Fotokopieren Photocopying Kinley Lange, I Will Lift My Weary Eyes • SATB • © 2019 HELBLING grundsätzlich this copyright AUSTRIA: Kaplanstrasse 9, 6063 Rum/Innsbruck | GERMANY: P.O. -

Mexico Is the Number One Consumer of Coca-Cola in the World, with an Average of 225 Litres Per Person

Arca. Mexico is the number one Company. consumer of Coca-Cola in the On the whole, the CSD industry in world, with an average of 225 litres Mexico has recently become aware per person; a disproportionate of a consolidation process destined number which has surpassed the not to end, characterised by inventors. The consumption in the mergers and acquisitions amongst USA is “only” 200 litres per person. the main bottlers. The producers WATER & CSD This fizzy drink is considered an have widened their product Embotelladoras Arca essential part of the Mexican portfolio by also offering isotonic Coca-Cola Group people’s diet and can be found even drinks, mineral water, juice-based Monterrey, Mexico where there is no drinking water. drinks and products deriving from >> 4 shrinkwrappers Such trend on the Mexican market milk. Coca Cola Femsa, one of the SMI LSK 35 F is also evident in economical terms main subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola >> conveyor belts as it represents about 11% of Company in the world, operates in the global sales of The Coca Cola this context, as well as important 4 installation. local bottlers such as ARCA, CIMSA, BEPENSA and TIJUANA. The Coca-Cola Company These businesses, in addition to distributes 4 out of the the products from Atlanta, also 5 top beverage brands in produce their own label beverages. the world: Coca-Cola, Diet SMI has, to date, supplied the Coke, Sprite and Fanta. Coca Cola Group with about 300 During 2007, the company secondary packaging machines, a worked with over 400 brands and over 2,600 different third of which is installed in the beverages. -

When in Rome, Beijing Or Brussels

When in Rome, Beijing or Brussels: Cultural Considerations of International Business Communication By Colin Gunn-Graffy A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Communication Boston College May, 2007 Copyright, Colin Gunn-Graffy © 2007 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements To my family, for their continued support, no matter what continent I’m on TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1 CHAPTER TWO: Things Go Worse for Coke: The Coca-Cola 12 Contamination Crisis in Belgium CHAPTER THREE: The Magic’s Gone: The Marketing Mistake 31 of Euro Disney in France CHAPTER FOUR: Looking Ahead: The Digital Age 55 and the Rising Markets of the East CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion 69 REFERENCES 74 1 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction Globalization and the Rise of Multinational Corporations Even before the Dutch sailed to the East Indies or Marco Polo traveled to China, people have been interacting with other cultures in numerous ways, many of them for economic reasons. One would imagine it was quite difficult initially for these people to communicate and do business with each other, but even today obstacles in international business still exist. Although our world has certainly become much smaller in the last several centuries, cultural and geographical contexts still play a large part in shaping different societies and their methods of interaction with others. The term “globalization” is one heard of quite often in today’s world, particularly in economic terms, referring to the expansion of free market capitalism. There are many other aspects that fit into the globalization process, ranging from political to social to technological, that are a part of this increasing interconnectivity of people around the world. -

When to Replace an Ingredient Cartridge

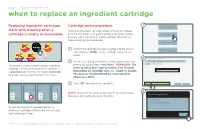

page 6 | productOperating replacement System System Configuration Service Menu Language when to replace an ingredient cartridge Dashboard Errors Alerts Notices Replacing ingredient cartridges Cartridge prime procedure. Replace Ingredients startsHFCS with knowingWater when aIce PrimingCarb an Water ingredient cartridgeProduct simply removesSwitches any And trapped Lighting User Interface Agitation Locks cartridge is empty or unavailable. air in the line and ensures guests receive a consistent, quality Prime beverage. After replacing an empty cartridge follow the on- screen messages outlined below: Manual Oerride Coke CokeZero DietCoke CFDietCoke Pibb Barqs Confirm the cartridge has been inserted into10 the / 26 /correct 14 Return To Dashboard 9 / 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14slot and press “PRIME”10 / 26 on / 14 the cartridge replacement 10 / 26 / 14 Operating System System Configuration Service Menu Language screen. Please prime/purge all newly inserted packages below: ERR User Mode: Crew Customer View Remove Dasani ingredient appear to be expired. 100% To Empty 100% To Empty 100% To Empty A new screen listing100% all brands/secondaryTo Empty flavors100%Operating Tothat Empty require System System100% To Configuration Empty Service Menu priming will appear. Press “Auto Prime”. REMINDER: The Prime Coke temporarily unavailable - needs agitation. TheSprite example above shows theMMLemonade cherry ingredient SeagramsGingerAle MelloYello HiC Powerade ® prime process lasts approximately 5-10 seconds cartridge is empty, as a result cherry vanilla Hi-C Please wait while the system agitates. 10 / 26 / 14 10 /® 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14depending on cartridge10 / 26 / 14 size, i.e., single10 / or26 / double.14 10 / 26 / 14 is grayed out and cherry Hi-C shows unavailable Please prime/purge all newly inserted packages below: when the user touches the cherry Hi-C® icon. -

A Guide to the Soft Drink Industry Acknowledgments

BREAKING DOWN THE CHAIN: A GUIDE TO THE SOFT DRINK INDUSTRY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was developed to provide a detailed understanding of how the soft drink industry works, outlining the steps involved in producing, distributing, and marketing soft drinks and exploring how the industry has responded to recent efforts to impose taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages in particular. The report was prepared by Sierra Services, Inc., in collaboration with the Supply Chain Management Center (SCMC) at Rutgers University – Newark and New Brunswick. The authors wish to thank Kristen Condrat for her outstanding support in all phases of preparing this report, including literature review and identifying source documents, writing, data analysis, editing, and final review. Special thanks also goes to Susanne Viscarra, who provided copyediting services. Christine Fry, Carrie Spector, Kim Arroyo Williamson, and Ayela Mujeeb of ChangeLab Solutions prepared the report for publication. ChangeLab Solutions would like to thank Roberta Friedman of the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity for expert review. For questions or comments regarding this report, please contact the supervising professors: Jerome D. Williams, PhD Prudential Chair in Business and Research Director – The Center for Urban Entrepreneurship & Economic Development (CUEED), Rutgers Business School – Newark and New Brunswick, Management and Global Business Department 1 Washington Park – Room 1040 Newark, NJ 07102 Phone: 973-353-3682 Fax: 973-353-5427 [email protected] www.business.rutgers.edu/CUEED Paul Goldsworthy Senior Industry Project Manager Department of Supply Chain Management & Marketing Sciences Rutgers Business School Phone: 908-798-0908 [email protected] Design: Karen Parry | Black Graphics The National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity (NPLAN) is a project of ChangeLab Solutions. -

2020 CDP Water Response

The Coca-Cola Company - Water Security 2020 W0. Introduction W0.1 (W0.1) Give a general description of and introduction to your organization. The Coca-Cola Company (NYSE: KO) is here to refresh the world and make a difference. We craft the brands and choice of drinks that people love. We do this in ways that create a more sustainable business. It’s about working together to create a better shared future for our people, our communities and our planet. The Coca-Cola Company is a total beverage company that markets, manufactures and sells beverage concentrates and syrups and finished beverages, offering over 500 brands and more than 4,700 products in over 200 countries and territories. In our concentrate operations, The Coca‑Cola Company typically generates net operating revenues ($37.3 billion in 2019) by selling concentrates and syrups to authorized bottling partners. Our bottling partners combine the concentrates and syrups with still or sparkling water and sweeteners (depending on the product), to prepare, package, sell and distribute finished beverages. Our finished product operations consist primarily of company-owned or -controlled bottling, sales and distribution operations. The 37 countries listed under question C0.3 are those countries in which The Coca-Cola Company owns and operates bottling plants. In addition to the company’s Coca-Cola brands, our portfolio includes some of the world’s most valuable beverage brands, such as AdeS soy-based beverages, Ayataka green tea, Dasani waters, Del Valle juices and nectars, Fanta, Georgia coffee, Gold Peak teas and coffees, Honest Tea, innocent smoothies and juices, Minute Maid juices, Powerade sports drinks, Simply juices, smartwater, Sprite, vitaminwater and ZICO coconut water. -

Coca-Colonization and Hybridization of Diets Among the Tz'utujil Maya Jason M

This article was downloaded by: [Jason Nagata] On: 12 July 2011, At: 00:01 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Ecology of Food and Nutrition Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gefn20 Coca-Colonization and Hybridization of Diets among the Tz'utujil Maya Jason M. Nagata a , Frances K. Barg b , Claudia R. Valeggia c & Kent D. W. Bream d a Health and Societies Program, Department of History and Sociology of Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA b Department of Anthropology and Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA c Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA d Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Available online: 11 Jul 2011 To cite this article: Jason M. Nagata, Frances K. Barg, Claudia R. Valeggia & Kent D. W. Bream (2011): Coca-Colonization and Hybridization of Diets among the Tz'utujil Maya, Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 50:4, 297-318 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2011.568911 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. -

Beers Spirits Liqueurs Soft Drink & Juice

Beers We recommend Peroni, Italy’s beer! Peroni 7 Peroni Leggera (3.5%, LC) 6 Cascade Premium Light (2.6%) 5.5 Crown Lager 7 XXXX Gold (3.5%) 6 Lord Nelson Old Admiral Dark Ale 7.5 Corona 7.5 Lord Nelson 3 Sheets Pale Ale 7.5 Pure Blonde 6.5 Napoleone & Co. Apple Cider 7.5 Napoleone & Co. Pear Cider 7.5 Spirits mixer add 1 Smirnoff Red Vodka 5.5 Absolut Vodka 6.5 Jim Beam White Label 5.5 Jack Daniels Whiskey 6.5 Wild Turkey Bourbon 6.5 Johnnie Walker Red 5.5 Johnnie Walker Black 6.5 Glenfiddoch Single Malt 7 Bundaberg Rum 5.5 Bacardi White Rum 5.5 Appleton’s V/X Rum 6.5 Gordon’s Gin 5.5 Bombay Sapphire Gin 6.5 Dorville Brandy 5.5 Jose Cuervo Anejo Tequila 6.5 Liqueurs all 6.5 Suntory Midori Kahlúa Tia Maria Bailey’s Irish Cream Chambord Marie Brizzard Peach Liqueur Von Schutters Butterscotch Schnapps Campari Aperol Orange Galliano Liqueur Galliano Sambuca Galliano Black Sambuca Galliano Amaretto Cointreau Frangelico Southern Comfort Malibu Soft Drink & Juice Orange, Apple, Pineapple, Cranberry & Tomato Juice 4 Coke, Diet Coke, Sprite, Ginger Ale, Soda, Lift, Fanta, Tonic Water 3.8 Coke 250ml, Diet Coke 250ml, Coke Zero 250ml, Lift 250ml, Fanta 250ml, Sprite 250ml 4 San Benedetto Still / Sparkling Water 4.5 Coffee by Giancarlo - Traditionale Blend Short Black 3.3 Long Black 4 Flat White 4 Cappuccino 4 Latte 4.3 Short Macchiato 3.6 Long Macchiato 4.2 Hot Chocolate 4.5 Hot Mocha 5 Affogato 5 Chai Latte 5 Mellocino 4.5 Vienna 5 Iced Chocolate 5.5 Iced Coffee 5.5 Iced Mocha 5.5 Extra Shot 0.8 Soy Milk 0.8 Decaf 0.8 Mug Upsize 1.1 Coffee Flavoured -

South Africa

MOSAIC SOUTH AFRICA Illustration by1 Christina Liang Albert Gallatin Scholars The Arts in Times of Social Change Stephen Brown | Lisbeth Carney | Brandon Green EDITORS Maomao Hu | Patrick McCreery DESIGNER Maomao Hu Melissa Daniel Publication Managers Brandon Green This issue of Mosaic represents the collaborative efforts of many people. We wish to thank: Michael Dinwiddie | Patrick McCreery Scholars Advisers, 2010-2011 Nicole Cohen | Joseph Pisano Susanne Wofford | Lisa Goldfarb Gallatin Deans Linda Wheeler Reiss | Kimberly DaCosta Masauko Chipembere | Kevin Hylton | Ricardo Khan Faculty and Guest Mkhululi Mabija | Sibusiso Mamba | Vasuki Nesiah Speakers, Fall 2010 Jabulani Chen Pereira Adam Carter and his colleagues In the United states at Destination Partners Sedica Davids | Sue Krige | Zanele Muholi | Riason Naidoo In south africa Michael Stevenson Gallery (Cape Town) | Zulwini Tours Market Photo Workshop (Jo’burg) We wish to offer a heartfelt special thanks to Thomas Harms, our guide ex- traordinaire, who went above and beyond to help us understand his country. Table of contents 1 Introduction Brittany Habermehl & Paolina Lu 3 The Flux of Tongues and Power Cameron Martin 8 Schools of Struggle Revolutionary Student Leadership in Soweto Daniel Jones 12 class and race Contemporary South africa Lauren Wilfong 16 Finding Evita Ryan Weldon 21 Fighting aids in south africa tradition meets modernity Dipika Gaur 25 Connection or contrivance? Apartheid and the Holocaust Matthew S. Berenbaum 30 South Africa and South Korea Gina Hong 34 I’M just -

Automated Cleaning-In-Place Crucial for Beverage Plant Operation Coca-Cola Beverages, Czech Republic Case Story

Automated Cleaning-in-Place crucial for beverage plant operation Coca-Cola Beverages, Czech Republic Case story Being a clear leader in the Czech soft drink market, Coca-Cola has a long history in the region. The first bottles of Coke arrived to the country in 1945 along with U.S. allied troops liberating the western part of Bohemia from the Nazi rule. More than two decades later, the famous drink has been produced here for the first time in the state-owned enterprise in Brno in 1968. Today, Coca-Cola Beverages Czech Republic (CCB), member of Coca-Cola HBC Group is a sole Coca-Cola franchise operator for the Czech market. It is a total beverage company, producing, distributing and selling all categories of non-alcohol drinks. The wide range of its products includes Coca-Cola, Coca-Cola Light, Cherry Coke, Fanta flavours, Sprite, Kinley Tonic Water, Lift flavours, various Cappy flavours, including Cappy Ice Fruit nectars, Bonaqua bottled water (including flavoured versions), Powerade sports drink, Burn energy drink, Nestea Ice Tea, Nescafé and Nescafé Xpress. In the Czech Republic, CCB operates one production facility in Kyje and 10 sales and administration centres around the country. The production, distribution and sales of its beverages directly gives an employment to almost 1300 people. The heart of the Coca-Cola Beverages Czech Republic production is located in Prague’s Kyje district, where the company operates its bottling plant. Efficient cleaning of the piping systems, tanks and filling machines is crucial both for the famed product quality and for keeping up with the high production volumes. -

Sustainability Report 2013 5 Our COMPANY

About Coca-Cola FEMSA GRI 2.1, 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, 2.6 and 2.7 Coca-Cola FEMSA, S.A.B. de C.V. produces and distributes Coca-Cola, Fanta, Sprite, Del Valle and other trademark beverages of The Coca-Cola Company in Mexico (a substantial part of Central Mexico, including Mexico City as well as the Southern and the Northeast of the country), Guatemala (Guatemala City and surrounding areas), Nicaragua (nationwide), Costa Rica (nationwide), Panama (nationwide), Colombia (most of the country), Venezuela (nationwide), Brazil (Greater São Paulo, Campiñas, Santos the State of Mato Grosso do Sul, the State of Paraná, part of the State of Goias, part of the State of Río de Janeiro and part of the State of Minas Gerais), Argentina (Federal Capital of Buenos Aires and surrounding areas) and the Philippines (nationwide), along with bottled water, juices, teas, isotonic sports drinks, beer and other beverages in some of these territories. The Company has 64 bottling facilities and serves more than 346 million consumers, approximately through 2,900,000 retailers, with more than 120,000 employees worldwide. The company’s capital stock is owned 47.9% by Fomento Económico Mexicano, S.A.B. de C.V. (FEMSA), 28.1% by wholly owned subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola Company and 24.0% by the public. The publicly traded shares of KOF are Series L shares with limited voting rights that are listed on the Bolsa Mexican de Valores (BMV: KOF L) and as American Depositary Receipts (ADSs) on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE: KOF). -

Coca-Cola, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Branding in the Twentieth Century

The Company that Taught the World to Sing: Coca-Cola, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Branding in the Twentieth Century by Laura A. Hymson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor, James W. Cook, Chair Professor Philip J. Deloria Professor Susan J. Douglass Professor Penny Von Eschen © Laura A. Hymson 2011 Acknowledgements I owe an extraordinary debt to the people and institutions that helped and supported me as I worked to complete this dissertation. While working on this project, I spent time in several cities, including: Ann Arbor, New York, Atlanta, Urbana- Champagne, Alexandria, Washington, D.C, Newark, and Hartford. In all of these places where I have lived, researched, or taught, I have been shown incredible kindness and I am grateful for everyone who has helped me along the way. Thanks first to the chair of my dissertation committee, Jay Cook, who has been exceptionally generous with his time. Without his insightful feedback, invaluable advice, and thoughtful comments this dissertation would not have been possible. I can only hope to be as effective and compassionate as a teacher and mentor as he has been to me. My entire dissertation committee was composed of scholars whose work I truly admire and I am grateful for the time they devoted to my ideas and my work. Penny Von Eschen and Phil Deloria provided important feedback on drafts, and made suggestions for research and writing that helped advance my thinking on a number key issues at the heart of this project.