When in Rome, Beijing Or Brussels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Will Lift My Weary Eyes • SATB • © 2019 HELBLING Grundsätzlich This Copyright AUSTRIA: Kaplanstrasse 9, 6063 Rum/Innsbruck | GERMANY: P.O

2 I Will I WillLift Lift My My WearyWeary Eyes Eyes Lyrics: Kinley Lange, based on Psalm 121 Music: Kinley Lange *) Freely, plaintively S 4 4 A 4 4 mf (solo or section) T 4 4 And I will lift my wear y eyes, I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the B 4 4 5 (tutti) help that I have need ed will sure ly tum ble down, I will lift my eyes un to the hills. And I will 9 G CG D mf And the mf Hm I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the lift my wear y eyes, I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the • The vowels should be very bright and open, a bit nasal in quality, and the singing should be without vibrato. Many of the upward-moving intervals, as well as certain repeated notes, should be embellished with a scoop or slight grace-note glissando from beneath. Take care not to over-do this as it is primarily a soloistic embellishment and could easily become overbearing in choral singing. • The piece can be performed with traditional Blue Grass instruments. If so, it is recommended that a bass not be used as it could be in conflict with the sung bass line. Mandolin, violin and guitar will work nicely, following the indicated chords. *) Optional fiddle drone accompaniment til bar 8 Fotokopieren Photocopying Kinley Lange, I Will Lift My Weary Eyes • SATB • © 2019 HELBLING grundsätzlich this copyright AUSTRIA: Kaplanstrasse 9, 6063 Rum/Innsbruck | GERMANY: P.O. -

From Notice-And-Takedown to Notice-And-Delist: Implementing Google Spain

FINAL KUCZERAWY AND AUSLOOS 4.5.16 (DO NOT DELETE) 5/9/16 11:51 AM FROM NOTICE-AND-TAKEDOWN TO NOTICE-AND-DELIST: IMPLEMENTING GOOGLE SPAIN ALEKSANDRA KUCZERAWY AND JEF AUSLOOS* INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 220 A. Media Storm ........................................................................... 220 B. Internet Law Crossroads ........................................................ 221 I. HOW DID WE GET HERE? .............................................................. 223 A. Google Spain .......................................................................... 223 1. Facts of the Case ............................................................... 223 2. Scope ............................................................................... 224 3. Right to be Delisted .......................................................... 224 4. Balancing .......................................................................... 225 B. Implementation of Google Spain ............................................ 226 1. Online Form ...................................................................... 226 2. Advisory Council .............................................................. 227 3. Article 29 Working Party ................................................. 228 4. Emerging Body of Case Law ........................................... 228 II. HAVE WE MET BEFORE? ............................................................... 229 A. Dazed and Confused: Criticism of Google -

Mexico Is the Number One Consumer of Coca-Cola in the World, with an Average of 225 Litres Per Person

Arca. Mexico is the number one Company. consumer of Coca-Cola in the On the whole, the CSD industry in world, with an average of 225 litres Mexico has recently become aware per person; a disproportionate of a consolidation process destined number which has surpassed the not to end, characterised by inventors. The consumption in the mergers and acquisitions amongst USA is “only” 200 litres per person. the main bottlers. The producers WATER & CSD This fizzy drink is considered an have widened their product Embotelladoras Arca essential part of the Mexican portfolio by also offering isotonic Coca-Cola Group people’s diet and can be found even drinks, mineral water, juice-based Monterrey, Mexico where there is no drinking water. drinks and products deriving from >> 4 shrinkwrappers Such trend on the Mexican market milk. Coca Cola Femsa, one of the SMI LSK 35 F is also evident in economical terms main subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola >> conveyor belts as it represents about 11% of Company in the world, operates in the global sales of The Coca Cola this context, as well as important 4 installation. local bottlers such as ARCA, CIMSA, BEPENSA and TIJUANA. The Coca-Cola Company These businesses, in addition to distributes 4 out of the the products from Atlanta, also 5 top beverage brands in produce their own label beverages. the world: Coca-Cola, Diet SMI has, to date, supplied the Coke, Sprite and Fanta. Coca Cola Group with about 300 During 2007, the company secondary packaging machines, a worked with over 400 brands and over 2,600 different third of which is installed in the beverages. -

Mashing-Up Maps Google Geo Services and the Geography Of

Mashing-up Maps Google Geo Services and the Geography of Ubiquity Craig M. Dalton A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Department of Geography. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Dr. Scott Kirsch Dr. Banu Gokariksel Dr. Kenneth Hillis Dr. John Pickles Dr. Sarah Sharma © 2012 Craig M. Dalton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CRAIG DALTON: Mashing-up Maps: Google Geo Services and the Geography of Ubiquity (Under the direction of Scott Kirsch) How are Google geo services such as Google Maps and Google Earth shaping ways of seeing the world? These geographic ways of seeing are part of an influential and problematic geographic discourse. This discourse reaches hundreds of millions of people, though not all have equal standing. It empowers many people to make maps on the geoweb, but within the limits of Google’s business strategy. These qualities, set against the state-centeredness of mapmaking over the last six hundred years, mark the Google geo discourse as something noteworthy, a consumer-centered mapping in a popular geographic discourse. This dissertation examines the Google geo discourse through its social and technological history, Google’s role in producing and limiting the discourse, and the subjects who make and use these maps. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation was only possible with the help of a large number of people. I owe each a debt of gratitude. Chief among them is a fantastic advisor, Scott Kirsch. His patience, grace, and good criticism saw me through the trials of graduate school. -

Google Prevails in Fair Use Case on Book Digitization Project

CHICAGOLAWBULLETIN.COM TUESDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2013 ® Volume 159, No. 241 Google prevails in fair use case on book digitization project o o g l e ’s unofficial slo- braries would be a logistic im- reader, as well. The author gets gan “D o n’t be evil” p o s s i b i l i t y. her royalty on the sales. And sets a pretty low bar So Google addressed the prob- INSIDE IP LAW Google has taken a small step to- as a standard of cor- lem in a bold and controversial ward its mission of making in- porate conduct. way. Rather than seeking permis- formation universally accessible GMaybe that’s why the company is sion from publishers and authors and useful. so often the subject of criticism. to scan copyrighted books, Google C h i n ’s decision is an excellent The Google-haters are numer- scanned all the books and an- WILLIAM T. example of a ruling that achieves ous and the complaints are stri- nounced that if any copyright the ultimate goal of copyright law dent: Google invades our privacy, owner did not want its book in- MCGR AT H —to promote the dissemination it reads our e-mail, it allows cen- cluded in the project, Google of knowledge and the advance- sorship in China, it is unfair in its would gladly remove it. In other William T. McGrath is a member of Davis, ment of learning, while also pro- page rankings and it has inun- words, authors and publishers McGrath LLC, where he handles copyright, viding an economic benefit to the dated us with advertisements. -

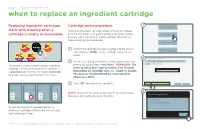

When to Replace an Ingredient Cartridge

page 6 | productOperating replacement System System Configuration Service Menu Language when to replace an ingredient cartridge Dashboard Errors Alerts Notices Replacing ingredient cartridges Cartridge prime procedure. Replace Ingredients startsHFCS with knowingWater when aIce PrimingCarb an Water ingredient cartridgeProduct simply removesSwitches any And trapped Lighting User Interface Agitation Locks cartridge is empty or unavailable. air in the line and ensures guests receive a consistent, quality Prime beverage. After replacing an empty cartridge follow the on- screen messages outlined below: Manual Oerride Coke CokeZero DietCoke CFDietCoke Pibb Barqs Confirm the cartridge has been inserted into10 the / 26 /correct 14 Return To Dashboard 9 / 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14slot and press “PRIME”10 / 26 on / 14 the cartridge replacement 10 / 26 / 14 Operating System System Configuration Service Menu Language screen. Please prime/purge all newly inserted packages below: ERR User Mode: Crew Customer View Remove Dasani ingredient appear to be expired. 100% To Empty 100% To Empty 100% To Empty A new screen listing100% all brands/secondaryTo Empty flavors100%Operating Tothat Empty require System System100% To Configuration Empty Service Menu priming will appear. Press “Auto Prime”. REMINDER: The Prime Coke temporarily unavailable - needs agitation. TheSprite example above shows theMMLemonade cherry ingredient SeagramsGingerAle MelloYello HiC Powerade ® prime process lasts approximately 5-10 seconds cartridge is empty, as a result cherry vanilla Hi-C Please wait while the system agitates. 10 / 26 / 14 10 /® 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14depending on cartridge10 / 26 / 14 size, i.e., single10 / or26 / double.14 10 / 26 / 14 is grayed out and cherry Hi-C shows unavailable Please prime/purge all newly inserted packages below: when the user touches the cherry Hi-C® icon. -

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 30 Nov 2010 15:03:55 UTC Contents Articles Google 1 Criticism of Google 20 AdWords 33 AdSense 39 List of Google products 44 Blogger (service) 60 Google Earth 64 YouTube 85 Web search engine 99 User:Moonglum/ITEC30011 105 References Article Sources and Contributors 106 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 112 Article Licenses License 114 Google 1 Google [1] [2] Type Public (NASDAQ: GOOG , FWB: GGQ1 ) Industry Internet, Computer software [3] [4] Founded Menlo Park, California (September 4, 1998) Founder(s) Sergey M. Brin Lawrence E. Page Headquarters 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Eric E. Schmidt (Chairman & CEO) Sergey M. Brin (Technology President) Lawrence E. Page (Products President) Products See list of Google products. [5] [6] Revenue US$23.651 billion (2009) [5] [6] Operating income US$8.312 billion (2009) [5] [6] Profit US$6.520 billion (2009) [5] [6] Total assets US$40.497 billion (2009) [6] Total equity US$36.004 billion (2009) [7] Employees 23,331 (2010) Subsidiaries YouTube, DoubleClick, On2 Technologies, GrandCentral, Picnik, Aardvark, AdMob [8] Website Google.com Google Inc. is a multinational public corporation invested in Internet search, cloud computing, and advertising technologies. Google hosts and develops a number of Internet-based services and products,[9] and generates profit primarily from advertising through its AdWords program.[5] [10] The company was founded by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, often dubbed the "Google Guys",[11] [12] [13] while the two were attending Stanford University as Ph.D. -

A Guide to the Soft Drink Industry Acknowledgments

BREAKING DOWN THE CHAIN: A GUIDE TO THE SOFT DRINK INDUSTRY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was developed to provide a detailed understanding of how the soft drink industry works, outlining the steps involved in producing, distributing, and marketing soft drinks and exploring how the industry has responded to recent efforts to impose taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages in particular. The report was prepared by Sierra Services, Inc., in collaboration with the Supply Chain Management Center (SCMC) at Rutgers University – Newark and New Brunswick. The authors wish to thank Kristen Condrat for her outstanding support in all phases of preparing this report, including literature review and identifying source documents, writing, data analysis, editing, and final review. Special thanks also goes to Susanne Viscarra, who provided copyediting services. Christine Fry, Carrie Spector, Kim Arroyo Williamson, and Ayela Mujeeb of ChangeLab Solutions prepared the report for publication. ChangeLab Solutions would like to thank Roberta Friedman of the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity for expert review. For questions or comments regarding this report, please contact the supervising professors: Jerome D. Williams, PhD Prudential Chair in Business and Research Director – The Center for Urban Entrepreneurship & Economic Development (CUEED), Rutgers Business School – Newark and New Brunswick, Management and Global Business Department 1 Washington Park – Room 1040 Newark, NJ 07102 Phone: 973-353-3682 Fax: 973-353-5427 [email protected] www.business.rutgers.edu/CUEED Paul Goldsworthy Senior Industry Project Manager Department of Supply Chain Management & Marketing Sciences Rutgers Business School Phone: 908-798-0908 [email protected] Design: Karen Parry | Black Graphics The National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity (NPLAN) is a project of ChangeLab Solutions. -

2020 CDP Water Response

The Coca-Cola Company - Water Security 2020 W0. Introduction W0.1 (W0.1) Give a general description of and introduction to your organization. The Coca-Cola Company (NYSE: KO) is here to refresh the world and make a difference. We craft the brands and choice of drinks that people love. We do this in ways that create a more sustainable business. It’s about working together to create a better shared future for our people, our communities and our planet. The Coca-Cola Company is a total beverage company that markets, manufactures and sells beverage concentrates and syrups and finished beverages, offering over 500 brands and more than 4,700 products in over 200 countries and territories. In our concentrate operations, The Coca‑Cola Company typically generates net operating revenues ($37.3 billion in 2019) by selling concentrates and syrups to authorized bottling partners. Our bottling partners combine the concentrates and syrups with still or sparkling water and sweeteners (depending on the product), to prepare, package, sell and distribute finished beverages. Our finished product operations consist primarily of company-owned or -controlled bottling, sales and distribution operations. The 37 countries listed under question C0.3 are those countries in which The Coca-Cola Company owns and operates bottling plants. In addition to the company’s Coca-Cola brands, our portfolio includes some of the world’s most valuable beverage brands, such as AdeS soy-based beverages, Ayataka green tea, Dasani waters, Del Valle juices and nectars, Fanta, Georgia coffee, Gold Peak teas and coffees, Honest Tea, innocent smoothies and juices, Minute Maid juices, Powerade sports drinks, Simply juices, smartwater, Sprite, vitaminwater and ZICO coconut water. -

Coca-Colonization and Hybridization of Diets Among the Tz'utujil Maya Jason M

This article was downloaded by: [Jason Nagata] On: 12 July 2011, At: 00:01 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Ecology of Food and Nutrition Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gefn20 Coca-Colonization and Hybridization of Diets among the Tz'utujil Maya Jason M. Nagata a , Frances K. Barg b , Claudia R. Valeggia c & Kent D. W. Bream d a Health and Societies Program, Department of History and Sociology of Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA b Department of Anthropology and Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA c Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA d Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Available online: 11 Jul 2011 To cite this article: Jason M. Nagata, Frances K. Barg, Claudia R. Valeggia & Kent D. W. Bream (2011): Coca-Colonization and Hybridization of Diets among the Tz'utujil Maya, Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 50:4, 297-318 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2011.568911 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. -

Beers Spirits Liqueurs Soft Drink & Juice

Beers We recommend Peroni, Italy’s beer! Peroni 7 Peroni Leggera (3.5%, LC) 6 Cascade Premium Light (2.6%) 5.5 Crown Lager 7 XXXX Gold (3.5%) 6 Lord Nelson Old Admiral Dark Ale 7.5 Corona 7.5 Lord Nelson 3 Sheets Pale Ale 7.5 Pure Blonde 6.5 Napoleone & Co. Apple Cider 7.5 Napoleone & Co. Pear Cider 7.5 Spirits mixer add 1 Smirnoff Red Vodka 5.5 Absolut Vodka 6.5 Jim Beam White Label 5.5 Jack Daniels Whiskey 6.5 Wild Turkey Bourbon 6.5 Johnnie Walker Red 5.5 Johnnie Walker Black 6.5 Glenfiddoch Single Malt 7 Bundaberg Rum 5.5 Bacardi White Rum 5.5 Appleton’s V/X Rum 6.5 Gordon’s Gin 5.5 Bombay Sapphire Gin 6.5 Dorville Brandy 5.5 Jose Cuervo Anejo Tequila 6.5 Liqueurs all 6.5 Suntory Midori Kahlúa Tia Maria Bailey’s Irish Cream Chambord Marie Brizzard Peach Liqueur Von Schutters Butterscotch Schnapps Campari Aperol Orange Galliano Liqueur Galliano Sambuca Galliano Black Sambuca Galliano Amaretto Cointreau Frangelico Southern Comfort Malibu Soft Drink & Juice Orange, Apple, Pineapple, Cranberry & Tomato Juice 4 Coke, Diet Coke, Sprite, Ginger Ale, Soda, Lift, Fanta, Tonic Water 3.8 Coke 250ml, Diet Coke 250ml, Coke Zero 250ml, Lift 250ml, Fanta 250ml, Sprite 250ml 4 San Benedetto Still / Sparkling Water 4.5 Coffee by Giancarlo - Traditionale Blend Short Black 3.3 Long Black 4 Flat White 4 Cappuccino 4 Latte 4.3 Short Macchiato 3.6 Long Macchiato 4.2 Hot Chocolate 4.5 Hot Mocha 5 Affogato 5 Chai Latte 5 Mellocino 4.5 Vienna 5 Iced Chocolate 5.5 Iced Coffee 5.5 Iced Mocha 5.5 Extra Shot 0.8 Soy Milk 0.8 Decaf 0.8 Mug Upsize 1.1 Coffee Flavoured -

South Africa

MOSAIC SOUTH AFRICA Illustration by1 Christina Liang Albert Gallatin Scholars The Arts in Times of Social Change Stephen Brown | Lisbeth Carney | Brandon Green EDITORS Maomao Hu | Patrick McCreery DESIGNER Maomao Hu Melissa Daniel Publication Managers Brandon Green This issue of Mosaic represents the collaborative efforts of many people. We wish to thank: Michael Dinwiddie | Patrick McCreery Scholars Advisers, 2010-2011 Nicole Cohen | Joseph Pisano Susanne Wofford | Lisa Goldfarb Gallatin Deans Linda Wheeler Reiss | Kimberly DaCosta Masauko Chipembere | Kevin Hylton | Ricardo Khan Faculty and Guest Mkhululi Mabija | Sibusiso Mamba | Vasuki Nesiah Speakers, Fall 2010 Jabulani Chen Pereira Adam Carter and his colleagues In the United states at Destination Partners Sedica Davids | Sue Krige | Zanele Muholi | Riason Naidoo In south africa Michael Stevenson Gallery (Cape Town) | Zulwini Tours Market Photo Workshop (Jo’burg) We wish to offer a heartfelt special thanks to Thomas Harms, our guide ex- traordinaire, who went above and beyond to help us understand his country. Table of contents 1 Introduction Brittany Habermehl & Paolina Lu 3 The Flux of Tongues and Power Cameron Martin 8 Schools of Struggle Revolutionary Student Leadership in Soweto Daniel Jones 12 class and race Contemporary South africa Lauren Wilfong 16 Finding Evita Ryan Weldon 21 Fighting aids in south africa tradition meets modernity Dipika Gaur 25 Connection or contrivance? Apartheid and the Holocaust Matthew S. Berenbaum 30 South Africa and South Korea Gina Hong 34 I’M just