South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collectors Are Eating up Vintage Menus

$1.50 AntiqueWeek T HE W EEKLY A N T IQUE A UC T ION & C OLLEC T ING N E W SP A PER VOL. 53 ISSUE NO. 2685 www.antiqueweek.com MARCH 23, 2021 Collectors are eating up vintage menus By William Flood If you’re like most of us, it’s been quite a while since you’ve dined in a restaurant and ordered a meal from a menu held in your hands rather than from an app on your phone. Yet, did you know that what was once so common — the restaurant menu — is a popular collectible? Menu collecting is a niche within the larger ephemera collecting hobby and popular for many reasons. Menus have a nostalgic appeal, particularly for long-gone eateries that collectors recog- nize or have visited. Menus also pro- vide a fascinating economics lesson reflected in the age-old prices printed on their pages. Culinary trends and once-popular cuisine are also spotlight- ed as is the evolution of commercial printing and design. And, even though the most historic menus can cost thou- sands of dollars, menu collecting Above: Die-cut menus came in every shape imaginable, all intended to be unique mar- remains a relatively inexpensive hobby. keting tools for the restaurant. There is archeological evidence that something akin to menus once existed Below: This cocktail menu from the former Kahiki in Columbus shows the draw being cre- in China’s Song Dynasty — but menus ated by alluring pictures and exotic names like the “Fog Cutter.” as we know them date back to 18th-cen- tury Europe. -

March 2017 17Th a Religious Holiday

The Rocket Review Raritan High School’s Official Newspaper 39.6 million people claim to have Irish heritage, The Day of the Irish 127 million people will celebrate the holiday. That By: Thomas Grady is 7 times greater than Ireland’s population! March is a month full of holidays, but one that In Ireland, on the other hand, they did see St. stands out is St. Patrick’s Day. Every March 17th, Patrick’s Day as a religious holiday. In the 1970’s all of America celebrates their Irish heritage. the government would close the pubs in Ireland Though not a national holiday, many people take so they could get the people to go to church and off from work and studies to embrace the Irish pray for St. Patrick. But since the mid-90’s the spirit. The day of St. Pat’s isn’t really a celebra- government made it a joyous holiday, giving it a tion in Ireland, it’s more of a solemn affair. multi day festival in the capital of Dublin. They have festivals, dances, and a parade. Not only Ireland’s patron saint is recognized in America does this happen in Dublin, it happens all around because of Irish immigrants who made March Ireland. Careful because in the first paragraph, 2017 March 17th a religious holiday. The man for whom St. you state that it is serious in Ireland. Patrick’s Day is named was born into an aris- In closing, when you see March 17th coming up tocratic family in Roman Britain around the end in the calendar, grab your leprechaun hat, lucky of the fourth century. -

I Will Lift My Weary Eyes • SATB • © 2019 HELBLING Grundsätzlich This Copyright AUSTRIA: Kaplanstrasse 9, 6063 Rum/Innsbruck | GERMANY: P.O

2 I Will I WillLift Lift My My WearyWeary Eyes Eyes Lyrics: Kinley Lange, based on Psalm 121 Music: Kinley Lange *) Freely, plaintively S 4 4 A 4 4 mf (solo or section) T 4 4 And I will lift my wear y eyes, I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the B 4 4 5 (tutti) help that I have need ed will sure ly tum ble down, I will lift my eyes un to the hills. And I will 9 G CG D mf And the mf Hm I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the lift my wear y eyes, I’ll lift them up un to the hills, and the • The vowels should be very bright and open, a bit nasal in quality, and the singing should be without vibrato. Many of the upward-moving intervals, as well as certain repeated notes, should be embellished with a scoop or slight grace-note glissando from beneath. Take care not to over-do this as it is primarily a soloistic embellishment and could easily become overbearing in choral singing. • The piece can be performed with traditional Blue Grass instruments. If so, it is recommended that a bass not be used as it could be in conflict with the sung bass line. Mandolin, violin and guitar will work nicely, following the indicated chords. *) Optional fiddle drone accompaniment til bar 8 Fotokopieren Photocopying Kinley Lange, I Will Lift My Weary Eyes • SATB • © 2019 HELBLING grundsätzlich this copyright AUSTRIA: Kaplanstrasse 9, 6063 Rum/Innsbruck | GERMANY: P.O. -

Annual Review Judd Leighton School of Business and Economics

JUDD LEIGHTON SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS Annual Review JUDD LEIGHTON SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS I am also very involved in the community through different groups and organizations. I feel that it is really important to give back to your community. - KAREN BARNETT President and CEO, Valley Screen Process Annual Review 1. News 11. Speaker’s Series PRODUCED BY INDIANA UNIVERSITY SOUTH BEND 16. Alumni Interview OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS AND MARKETING GRAPHIC DESIGN 20. Community Awards & Sarah Perschbacher Recognitions PHOTOGRAPHY Sarah Perschbacher Peter Ringenberg 24. Student Recognitions Teresa Sheppard 40. Faculty PAPER: xpedx Endurance 70lb silk text COVER: xpedx Endurance 100lb silk text NOTE: xpedx is a Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified 42. Satisfied Customers vendor and supplies paper from renewable sources. 54. Special Thanks November 2015 58. Student Club 60. Dean’s Message NEWS Leighton School Makes Princeton Review For Eighth Consecutive Year The Judd Leighton School of Business P.N. Saksena, associate dean, graduate and Economics at Indiana University programs and accreditation. South Bend is listed once again as an “The Best 296 Business Schools” has outstanding business school, according The Judd Leighton School of Business and two-page profiles of the schools. Each to the education services company, the Economics is one of 280 in the U.S. and 16 profile addresses academics, career and Princeton Review. This is the eighth year international schools that are named. The placement, student life and environment, that the school has been included in listing is based on academic programs and admissions. The profiles also the annual publication, “The Best 296 and a review of institutional data collected have ratings for academic experience, Business Schools” (Random House / from each school. -

Coca Cola out of South Africa, but Is It the Real Thing?

Number Three The newsletter of Washington's STATE-WIDE ANTI-APARTHEID NETWORK COCA COLA OUT OF SOUTH AFRICA, BUT IS IT THE REAL THING? Inside this issue of SWAAN Call: The latest on the Coca-Cola campaign (page two) Congress passes historic sanctions bill (page 11) National day of protest on 10 October (page 3) PLUS: Regional updates, October/November Freedom Calendar, and more . .. Products of DOES APARTHEID The Coca-Cola Company Coca-Cola (classic, diet, cherry, etc.) GO BETTER WITH TAB Sprite Mello Yello Fresca Mr. PIBB Hi-C soft drinks Fanta Five-Alive COKE? Minute Maid Ju~ces Ramblin' root beer Bright and Early beverages Maryland Club coffee The Coca-Cola Company controls 90 percent Butter- Nut coffee of t he soft drink market in South Africa, Belmont Springs distilled water and is the third largest employer there, with 5,000 employees. Columbia Pictures Tri-Star Pictures (partial ownership) The company announced on 17 September that Embassy Television it c.Jould "disinvest" by selling its hold RCA/Columbia Pictures Home Video ings to black South African businessmen, Walter Reade theatres so the public was confused that the Georgia Coalition for Divestment did not *********************************** cancel plans to launch a nationwide Coke What the Coca-Cola Company has to say: Divestment Campaign on 10 October. WHY? The goal is to pressure Coca-Cola into "We have committed $10 million to the leading corporate withdrawal from South Equal Opportunity Funds, independent Sou~h Africa. This has not happened. African foundations which we are confident will play a major role in the shaping of "For one thing," according to the Wall post-apartheid South Africa. -

Mexico Is the Number One Consumer of Coca-Cola in the World, with an Average of 225 Litres Per Person

Arca. Mexico is the number one Company. consumer of Coca-Cola in the On the whole, the CSD industry in world, with an average of 225 litres Mexico has recently become aware per person; a disproportionate of a consolidation process destined number which has surpassed the not to end, characterised by inventors. The consumption in the mergers and acquisitions amongst USA is “only” 200 litres per person. the main bottlers. The producers WATER & CSD This fizzy drink is considered an have widened their product Embotelladoras Arca essential part of the Mexican portfolio by also offering isotonic Coca-Cola Group people’s diet and can be found even drinks, mineral water, juice-based Monterrey, Mexico where there is no drinking water. drinks and products deriving from >> 4 shrinkwrappers Such trend on the Mexican market milk. Coca Cola Femsa, one of the SMI LSK 35 F is also evident in economical terms main subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola >> conveyor belts as it represents about 11% of Company in the world, operates in the global sales of The Coca Cola this context, as well as important 4 installation. local bottlers such as ARCA, CIMSA, BEPENSA and TIJUANA. The Coca-Cola Company These businesses, in addition to distributes 4 out of the the products from Atlanta, also 5 top beverage brands in produce their own label beverages. the world: Coca-Cola, Diet SMI has, to date, supplied the Coke, Sprite and Fanta. Coca Cola Group with about 300 During 2007, the company secondary packaging machines, a worked with over 400 brands and over 2,600 different third of which is installed in the beverages. -

When in Rome, Beijing Or Brussels

When in Rome, Beijing or Brussels: Cultural Considerations of International Business Communication By Colin Gunn-Graffy A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Communication Boston College May, 2007 Copyright, Colin Gunn-Graffy © 2007 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements To my family, for their continued support, no matter what continent I’m on TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1 CHAPTER TWO: Things Go Worse for Coke: The Coca-Cola 12 Contamination Crisis in Belgium CHAPTER THREE: The Magic’s Gone: The Marketing Mistake 31 of Euro Disney in France CHAPTER FOUR: Looking Ahead: The Digital Age 55 and the Rising Markets of the East CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion 69 REFERENCES 74 1 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction Globalization and the Rise of Multinational Corporations Even before the Dutch sailed to the East Indies or Marco Polo traveled to China, people have been interacting with other cultures in numerous ways, many of them for economic reasons. One would imagine it was quite difficult initially for these people to communicate and do business with each other, but even today obstacles in international business still exist. Although our world has certainly become much smaller in the last several centuries, cultural and geographical contexts still play a large part in shaping different societies and their methods of interaction with others. The term “globalization” is one heard of quite often in today’s world, particularly in economic terms, referring to the expansion of free market capitalism. There are many other aspects that fit into the globalization process, ranging from political to social to technological, that are a part of this increasing interconnectivity of people around the world. -

Governance on Russia's Early-Modern Frontier

ABSOLUTISM AND EMPIRE: GOVERNANCE ON RUSSIA’S EARLY-MODERN FRONTIER DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Paul Romaniello, B. A., M. A. The Ohio State University 2003 Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Eve Levin, Advisor Dr. Geoffrey Parker Advisor Dr. David Hoffmann Department of History Dr. Nicholas Breyfogle ABSTRACT The conquest of the Khanate of Kazan’ was a pivotal event in the development of Muscovy. Moscow gained possession over a previously independent political entity with a multiethnic and multiconfessional populace. The Muscovite political system adapted to the unique circumstances of its expanding frontier and prepared for the continuing expansion to its east through Siberia and to the south down to the Caspian port city of Astrakhan. Muscovy’s government attempted to incorporate quickly its new land and peoples within the preexisting structures of the state. Though Muscovy had been multiethnic from its origins, the Middle Volga Region introduced a sizeable Muslim population for the first time, an event of great import following the Muslim conquest of Constantinople in the previous century. Kazan’s social composition paralleled Moscow’s; the city and its environs contained elites, peasants, and slaves. While the Muslim elite quickly converted to Russian Orthodoxy to preserve their social status, much of the local population did not, leaving Moscow’s frontier populated with animists and Muslims, who had stronger cultural connections to their nomadic neighbors than their Orthodox rulers. The state had two major goals for the Middle Volga Region. -

A Decolonial Reading of Psalm 137 in Light of South Africa's Struggle Songs

464 Ramantswana, “Reading of Psalm 137,” OTE 32/2 (2019): 464-490 Song(s) of Struggle: A Decolonial Reading of Psalm 137 in Light of South Africa’s Struggle Songs HULISANI RAMANTSWANA (UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA) ABSTRACT This article engages in a decolonial reading of Ps 137 in light of South African songs of struggle. In this reading, Ps 137 is regarded as an epic song which combines struggle songs which originated within the golah community in response to the colonial relations between the oppressor and the oppressed. The songs of struggle then gained new life during the post-exilic period as a result of the new colonial relation between the Yehud community and the Persian Empire. Therefore, Ps 137 should be viewed as not a mere song, but an anthology of songs of struggle: a protest song (vv. 1-4), a sorrow song (vv. 5-6), and a war song (vv. 7- 9). KEYWORDS: Psalm 137, Songs of Struggle, protest song, sorrow song, war song, exile, Babylon, post-exilic, Persian Empire. A INTRODUCTION Bob Becking, in a paper entitled “Does Exile Equal Suffering? A Fresh Look at Psalm 137,”1 argues that exile and diaspora for the exiles who were in Babylon did not so much amount to things such as hunger and oppression or economic hardship; instead, it was more a feeling of alienation which resulted in the longing to return to Zion. Becking’s interpretation of Ps 137 tends to minimise the colonial dynamics involved in the relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed, the coloniser and the colonised, which continually pushes the oppressed into the zone of nonbeing. -

When to Replace an Ingredient Cartridge

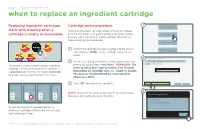

page 6 | productOperating replacement System System Configuration Service Menu Language when to replace an ingredient cartridge Dashboard Errors Alerts Notices Replacing ingredient cartridges Cartridge prime procedure. Replace Ingredients startsHFCS with knowingWater when aIce PrimingCarb an Water ingredient cartridgeProduct simply removesSwitches any And trapped Lighting User Interface Agitation Locks cartridge is empty or unavailable. air in the line and ensures guests receive a consistent, quality Prime beverage. After replacing an empty cartridge follow the on- screen messages outlined below: Manual Oerride Coke CokeZero DietCoke CFDietCoke Pibb Barqs Confirm the cartridge has been inserted into10 the / 26 /correct 14 Return To Dashboard 9 / 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14slot and press “PRIME”10 / 26 on / 14 the cartridge replacement 10 / 26 / 14 Operating System System Configuration Service Menu Language screen. Please prime/purge all newly inserted packages below: ERR User Mode: Crew Customer View Remove Dasani ingredient appear to be expired. 100% To Empty 100% To Empty 100% To Empty A new screen listing100% all brands/secondaryTo Empty flavors100%Operating Tothat Empty require System System100% To Configuration Empty Service Menu priming will appear. Press “Auto Prime”. REMINDER: The Prime Coke temporarily unavailable - needs agitation. TheSprite example above shows theMMLemonade cherry ingredient SeagramsGingerAle MelloYello HiC Powerade ® prime process lasts approximately 5-10 seconds cartridge is empty, as a result cherry vanilla Hi-C Please wait while the system agitates. 10 / 26 / 14 10 /® 26 / 14 10 / 26 / 14depending on cartridge10 / 26 / 14 size, i.e., single10 / or26 / double.14 10 / 26 / 14 is grayed out and cherry Hi-C shows unavailable Please prime/purge all newly inserted packages below: when the user touches the cherry Hi-C® icon. -

The Smoke That Calls: Insurgent Citizenship, Collective Violence and the Struggle for a Place in the New South Africa

CSVR Final Cover 7/6/11 1:36 PM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The smoke that calls Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and th violence citizenship, collective Insurgent Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. in the new a place for and the struggle violence citizenship, collective Insurgent Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. The smoke that calls that calls The smoke The smoke Eight case studies of community protest and xenophobic violence www.csvr.org.za www.swopinstitute.org.za Karl von Holdt, Malose Langa, Sepetla Molapo, Nomfundo Mogapi, Kindiza Ngubeni, Jacob Dlamini and Adele Kirsten Composite CSVR Final Cover 7/7/11 9:51 AM Page 2 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Published: July 2011 Copyright 2011 ® Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation | Society, Work and Development Institute The smoke that calls: Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. Eight case studies of community protest and xenophobic violence Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Society, Work and Development Institute 4th Floor, Braamfontein Centre, 23 Jorissen Street, Braamfontein Faculty of Humanities PO Box 30778, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, 2017 University of the Witwatersrand Tel: +27 (0) 11 403 5650 | Fax: +27 (0) 11 339 6785 Private Bag 3, Wits, 2050 Cape Town Office Tel: +27 (0) 11 717 4460 501 Premier Centre, 451 Main Road, Observatory, 7925 Tel: +27 (0) 21 447 3661 | Fax: +27 (0) 21 447 5356 email: [email protected] www.csvr.org.za www.swopinstitute.org.za Composite CSVR - Chapter 1 - 5 7/6/11 1:52 PM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The smoke that calls Insurgent citizenship, collective violence and the struggle for a place in the new South Africa. -

AUTHENTIC ATLANTA ITINERARY Atlanta’S Peachtree Corridor Is Packed with Can’T-Miss Classics

AUTHENTIC ATLANTA ITINERARY Atlanta’s Peachtree Corridor is packed with can’t-miss classics. Whether you’ve got a few hours or a few days, use these tips and treks to create an authentic Atlanta experience! Centennial Olympic Park DAY 1 — DOWNTOWN grab a complimentary glass bottle of clas- sic formula Coca-Cola. Inside CNN Studio Tour Just across the street, Imagine It! The Children’s Museum of Atlanta MorninG features hands-on exhibits and activities where kids ages 8 and younger can learn Start your morning off with a splash! and explore. Whether it’s building a Georgia Aquarium – the world’s largest sandcastle, painting on the walls or aquarium – is an underwater wonderland, exploring the latest special exhibit, home to more than 100,000 creatures children will discover why it’s a smart from 500 species. Swimming, diving and place to play. Courtesy of Target Free lurking among the 10 million gallons of Second Tuesdays, all visitors can enjoy water, you’ll find dolphins, penguins, free admission from 1 p.m. until closing Hard Rock Cafe Atlanta beluga whales, sea otters, piranhas and on the second Tuesday of each month. so much more. Other wow-worthy the world’s largest Fountain of Rings. Enjoy year-round, family-friendly activities include AT&T Dolphin Tales, The Park also offers seasonal activities entertainment in Centennial Olympic Deepo’s Undersea 3D Wondershow, and such as Fourth Saturday Family Fun Days, Park. Right in the heart of downtown, the behind-the-scenes tours and lectures. free concerts April-September during home of the 1996 Olympic Games offers Next door, learn all about the world’s Wednesday WindDown and Music at concerts, festivals, seasonal activities and most beloved beverage at World of Noon every Tuesday and Thursday.