Eric Brown, Record-Breaking British Pilot and World War II Hero, Dies at 97 by ROBERT D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People and Planes: Technical Versus Social Narratives in Aviation Museums

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Museums Scotland Research Repository Brown, Ian (2018) People and Planes: Technical versus social narratives in aviation museums. Journal of Aeronautical History, 2018 (07). pp. 200-207. http://repository.nms.ac.uk/2121 Deposited on: 17 September 2018 NMS Repository – Research publications by staff of the National Museums Scotland http://repository.nms.ac.uk/ Journal of Aeronautical History Paper 2018/07 People and Planes: Technical versus social narratives in aviation museums Ian Brown Assistant Curator of Aviation, National Museums Scotland Abstract Redevelopment of two Second World War hangars at the National Museum of Flight in East Lothian provided an opportunity to re-interpret the museum collections. This short account of the project looks at the integrated incorporation of oral history recordings. In particular, it looks at the new approach taken to the interpretation of the museum’s Messerschmitt Me 163B-1a Komet rocket fighter. This uses oral histories from the only Allied pilot to make a powered flight in a Komet, and from a Jewish slave labourer who was forced to build aircraft for Nazi Germany. This focus on oral history, along with an approach to interpretation that emphasises social history, rather than technology, has proven popular with visitors and allowed the building of audiences. 1. INTRODUCTION Traditionally, transport museums and collections have focused on the technological history of their objects, producing Top Trump displays which look at the fastest, biggest, most mass-produced, etc. Colin Divall and Andrew Scott noted in 2001 that ‘transport museums followed some way behind other sorts of museums in dealing with social context.’ 1 These displays often include great detail about the engines and their performance, sometimes including extreme technical detail such as bore size, stroke length, etc. -

Minister's Letter

L e a f l e t Greenbank Parish Church Minister’s Letter Braidburn Terrace, EH10 6ES No 643 May 2015 Dear Friends Pulpit Diary A couple of weeks ago early church? Or was Je- the BBC showed a tel- sus pointing to himself May 3 evision programme as the rock? Or perhaps 9.30am First Sunday Service led by called “In the footsteps it was Peter’s faith in him World Mission of St Peter”. It was a re- that was the rock? At first 10.30am Morning Worship peat of a two–part doc- glance this looks like a umentary, filmed in the multiple choice question Holy Land and present- in an exam paper. May 10 ed by the actor David But we will never know 10.30am Morning Worship Suchet. I don’t remem- in which direction Jesus ber seeing it before. And was looking or point- May 17 this time round I only ing when he spoke these saw the first part, which words. And it could be 10.30am Morning Worship took you through the that Jesus or even the life of the apostle Simon Gospel writer was us- May 24 Peter from his early days until the death ing a piece of inspired word-play here and of Jesus. I would have liked to see the sec- more than one of the above options was 9.30 Pentecost Communion ond part of the programme which charts intended. This question, like many others 10.30am Morning Worship for Pentecost the transformation of Peter from impetu- that arise as we explore the Christian faith, ous, bewildered and grieving disciple into cannot be treated like a multiple choice May 31 respected leader of the early Church, and question in an exam paper. -

CAPT ERIC BROWN 21 January 1919-21 February 2016

ERIC ‘WINKLE’ BROWN CAPT ERIC BROWN 21 January 1919-21 February 2016 WORDS: NICHOLASJONES 28 www.aeroplanemonthly.comAEROPLANE APRIL2016 n17September 1939, the the 487 different types of aircraft flown. Most surprisingly of all, when we captain of HMS Courageous Butitwas during themany relaxed discussed hismeeting with Himmler, orderedthat his boat be mealswesharedin-between the filming Eric went into some detail as to what turnedinto windsoits days thatIbegan to learn moreabout followed, oncehis question about aircraftO could take off.Unknowingly, the man behind the records. These the arrest of Wernher vonBraun had he puthimself across thebow of U29, lunches quickly established apattern. unmasked the SS monster.Did Eric lurking nearbyunder the Irish Sea. The Thevenue was usually theRAF Club’s thereforeknowwhere Himmlerwas U-boat captainseizedthe moment. Running Horse Tavern, the best-value buried?“Yes!”, he replied —but this Twenty minutes later, Courageous pub in London. Eric habitually ordered wasone detail he would not divulge. hadsunk, leaving the Fleet Air Arm aSpanish omelette while Ihad the Onemight getpeopleknocking on the desperately shortofpilots. scampi, having wondered beforehand door,askingfor directions to thegrave Afew days latera20-year-old RAF which further astonishing stories he —and Eric always kept his address and officer saw anotice inviting pilotsto woulddivulge. telephone number in his‘Who’s Who’ transfertothe FAAtomake up its And he neverfailedtodivulge, forhis entry. shortfall.Champing at thebit for some memory was alwaysoutstanding. Once, That was so typically Eric. Therewas action during the tedium of the ‘phoney while lamenting the terrible news from atimewhen many famouspeople still war’,hevolunteered. Thus began the Syria that played on the bar’s television had theirnumbers in the telephone naval flying career of Capt Eric Melrose that day,hesuddenlytold me howhe book. -

DENHAMS Antique Sale 697 to Be Held on 03Rd August of 2016

DENHAMS Antique sale 697 to be held on 03rd August of 2016 INDEX AND ORDER OF SALE START LOT European and Oriental Ceramic and Glassware 1 Sale starts at 10am Items from the Estate of Captain Eric 'Winkle' Brown' 151 Not before 11.15am Metalware, Collectors Items, Ephemera, Carpets, Fabrics, Toys, Curios etc 178 Not before 11.30am Oil Painting, Watercolours and Prints 417 Not before 1pm Silver, Silver Plated items, Jewellery & Objects of Virtue 497 Not before 1.30pm Clocks and Scientific Instruments 796 Not before 3.15pm Rugs and Carpets 825 Not before 3.30pm Antique and Fine Quality Furniture 857 Not before 3.30pm PUBLIC VIEWING Friday 29th July 9am - 5pm Saturday 30th July 9am - 12 noon Monday 1st August 9am - 5.30pm Tuesday 2nd August 9am - 7pm Wednesday 3rd August 9am - 10am IMPORTANT NOTICES PHONE BIDS Limited telephone bidding is available for Antique auctions, please ensure lines are booked by no later than 5pm Tuesday, prior to the Auction. BIDDING Prior to bidding you will be required to register for a Paddle Number, two forms of identity with proof of address and a home telephone number will be required. COMMISSION Buyers Premium of 15% plus vat (18% inclusive) is payable on the hammer price of every lot. PAYMENT Payment is welcome by debit and credit card. (there is a 3.5% surcharge on invoices for credit cards). Payment by cheque is not accepted. CLEARING Clearing of SMALL items is allowed during the auction for a £1 per lot 'fine' that is donated to charity DELIVERY For delivery of furniture we recommend Libbys Transport 01306 886755 or mobile 07831 799319 Page 1/51 European and Oriental Ceramic and Glassware IMPORTANT - All lots are sold as seen. -

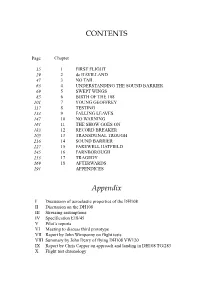

Sound Barrier Indexedmaster.Indd

9 CONTENTS Page Chapter 15 1 FIRST FLIGHT 29 2 de HAVILLAND 47 3 NO TAIL 63 4 UNDERSTANDING THE SOUND BARRIER 69 5 SWEPT WINGS 85 6 BIRTH OF THE 108 101 7 YOUNG GEOFFREY 117 8 TESTING 133 9 FALLING LEAVES 147 10 NO WARNING 161 11 THE SHOW GOES ON 183 12 RECORD BREAKER 205 13 TRANSDUNAL TROUGH 216 14 SOUND BARRIER 227 15 FAREWELL HATFIELD 245 16 FARNBOROUGH 253 17 TRAGEDY 269 18 AFTERWARDS 291 APPENDICES Appendix I Discussion of aeroelastic properties of the DH108 II Discussion on the DH108 III Stressing assumptions IV Specification E18/45 V Pilot’s reports VI Meeting to discuss third prototype VII Report by John Wimpenny on flight tests VIII Summary by John Derry of flying DH108 VW120 IX Report by Chris Capper on approach and landing in DH108 TG/283 X Flight test chronology 10 11 INTRODUCTION It was an exciting day for schoolboy Robin Brettle, and the highlight of a project he was doing on test flying: he had been granted an interview with John Cunningham. Accompanied by his father, Ray, Robin knocked on the door of Canley, Cunningham’s home at Harpenden in Hertfordshire and, after the usual pleasantries were exchanged, Ray set up the tape recorder and Robin began his interview. He asked the kind of questions a schoolboy might be expected to ask, and his father helped out with a few more specific queries. As the interview drew to a close, Robin plucked up courage to ask a more personal question: ‘Were you ever scared when flying?’ Thinking that Cunningham would recall some life-or-death moments when under fire from enemy aircraft during nightfighting operations, father and son were very surprised at the immediate and direct answer: ‘Yes, every time I flew the DH108.’ Cunningham, always calm, resolute and courageous in his years as chief test pilot of de Havilland, was rarely one to display his emotions, but where this aircraft was concerned he had very strong feelings, and there were times during the 160 or so flights he made in the DH108 that he feared for his life - and on one occasion came close to losing it. -

The Development of the Angled-Deck Aircraft Carrier—Innovation And

Naval War College Review Volume 64 Article 5 Number 2 Spring 2011 The evelopmeD nt of the Angled-Deck Aircraft Carrier—Innovation and Adaptation Thomas C. Hone Norman Friedman Mark D. Mandeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Hone, Thomas C.; Friedman, Norman; and Mandeles, Mark D. (2011) "The eD velopment of the Angled-Deck Aircraft Carrier—Innovation and Adaptation," Naval War College Review: Vol. 64 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol64/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Hone et al.: The Development of the Angled-Deck Aircraft Carrier—Innovation an THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANGLED-DECK AIRCRAFT CARRIER Innovation and Adaptation Thomas C. Hone, Norman Friedman, and Mark D. Mandeles n late 2006, Andrew Marshall, the Director of the Office of Net Assessment in Ithe Office of the Secretary of Defense, asked us to answer several questions: Why had the Royal Navy (RN) developed the angled flight deck, steam catapult, and optical landing aid before the U.S. Navy (USN) did? Why had the USN not devel- oped these innovations, which “transformed carrier Dr. Hone is a professor at the Center for Naval Warfare design and made practical the wholesale use of Studies in the Naval War College, liaison with the Of- fice of the Chief of Naval Operations, and a former se- high-performance jet aircraft,” in parallel with the 1 nior executive in the Office of the Secretary of Defense RN? Once developed by the RN, how had these three and special assistant to the Commander, Naval Air Sys- tems Command. -

On the Aerodynamics of the Gloster E28 39 – a Historical Perspective.Pdf

THE AERONAUTICAL JOURNAL JUNE 2008 307 On the aerodynamics of the Gloster E28/39 – a historical perspective B. J. Brinkworth Hants, UK ABSTRACT As commissioned to demonstrate the feasibility of jet propulsion, the CD overall drag coefficient of wing or aircraft E28/39 needed to exceed the performance of contemporary fighters. CF overall skin friction coefficient of surface But Carter, the chief designer, took the opportunity to look further Cl lift coefficient of aerofoil ahead, and devised an aircraft in which the onset of compressibility CL overall lift coefficient of wing or aircraft effects was taken into account from the beginning of the design. Cm moment coefficient of aerofoil Successful operation over a wide speed range required a shrewd CM overall moment coefficient of wing or wing-on-body synthesis of previous experience and practice with uncertain material g acceleration due to gravity emerging from the research domain. The resulting aircraft showed no L length of surface in direction of flow significant aerodynamic vices, requiring only minor modifications from M Mach number its first flight to its participation in diving trials, that took it into hitherto rpm rotational speed, revolutions per minute unexplored regions of high subsonic speed. It proved to be fully worthy R Prandtl-Glauert mutiplier for effect of Mach number of its pivotal role at the beginning of a new era in aeronautics. Re Reynolds number The aerodynamic features of Carter’s design are reviewed in t maximum thickness of aerofoil section relation to the limited state of knowledge at the time. Drawing upon u/c undercarriage fragmented material, much not previously published, this study X fraction of length from leading edge enlarges upon, and in places amends, previous accounts of this notable machine. -

Flying German Aircraft of World War Ii Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WINGS OF THE LUFTWAFFE : FLYING GERMAN AIRCRAFT OF WORLD WAR II PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Captain Eric Brown | 288 pages | 15 Sep 2010 | Hikoki Publications | 9781902109152 | English | Ottringham, United Kingdom Wings of the Luftwaffe : Flying German Aircraft of World War II PDF Book Wingspan was 65 feet 10 inches, and the plane was driven by a pair of horsepower Junkers Jumo F engines. FAGr Nearly half the subjects died from the experiment, and the others were executed. Item added to your basket View basket. Within just 13 years however, the Nazi regime had formed a new air force that would quickly become one of the most sophisticated in the world. Best Selling in Nonfiction See all. The Philips firm was entrusted to produce the EC tube equipped radar. Despite the developments, the Me still remained a plane that needed big patience. Heater Fuel Filter F 4. Black boards in jacket. Wings of the Luftwaffe : Flying the Captured German Aircraft of World War II Eric Melrose Brown Hikoki Publications , - Seiten 0 Rezensionen During more than two decades of uninterrupted flying Eric 'Winkle' Brown enjoyed the most extraordinary career of any test pilot and no pilot has a logbook that lists a greater variety of aircraft types flown. The pages of Wings of the Luftwaffe present a fascinating and detailed collage of pilot reports on a truly astounding array of German aircraft, all presented in Brown's easy going, concise and imminently readable style. The long range-reconnaissance variants had three copies. Will be clean, not soiled or stained. However, the Luftwaffe was unable to achieve air superiority over Britain in the summer of that year — something that Hitler had set as a precondition for an invasion. -

Medals, Banknotes and Coins and Banknotes Medals

Wednesday 23 November 2016 Wednesday Knightsbridge, London MEDALS, BANKNOTES AND COINS MEDALS, BANKNOTES AND COINS | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 23 November 2016 23563 MEDALS, BANKNOTES AND COINS Wednesday 23 November 2016 at 10am Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS ENQUIRIES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street John Millensted The United States Government Knightsbridge + 44 (0) 20 7393 3914 has banned the import of ivory London SW7 1HH [email protected] into the USA. Lots containing www.bonhams.com ivory are indicated by the symbol Fulvia Esposito Ф printed beside the lot number VIEWING + 44 (0) 20 7393 3917 in this catalogue. Monday 21 November 2016 [email protected] 9am – 4.30pm Tuesday 22 November 2016 PRESS ENQUIRIES 9am – 4pm [email protected] BIDS CUSTOMER SERVICES +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Monday to Friday +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax 8.30am – 6pm To bid via the internet +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 please visit www.bonhams.com SALE NUMBER: Please note that bids should be 23563 submitted no later than 24 hours prior to the sale. CATALOGUE: £15 New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS bids. Failure to do this may result AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE in your bids not being processed. Please email [email protected] Bidding by telephone will only be with “Live bidding” in the subject accepted on a lot with the excess line 48 hours before the auction of £500. to register for this service. Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert -

Investigating Germany's Wartime Advanced Aviation Technology

VDI Verein Deutscher Ingenieure DGLR Hamburger Bezirksverein Arbeitskreis Luft- und Raumfahrt Deutsche Gesellschaft für Luft- und Raumfahrt Lilienthal-Oberth e.V. The Royal Aeronautical Society Hamburg Branch invites to a Lecture Investigating Germany’s Wartime Advanced Aviation Technology Captain Eric Brown, CBE. DSC. AFC. RN Just before the end of WW2, Capt. Eric Brown was enlisted to take a small scientific team into Germany and some of the liberated territories, to seek out aviation technology, before it was destroyed, or lost to the Russians. Eric and his team went to Air Bases and Research Facilities all over Germany and recovered data on jet and piston engines, aerodynamics, rocketry, weaponry and ancillary equipment. Eric was able to fly many different types of German aircraft, with a little help from captured Luftwaffe personnel. During the lecture Eric will describe his experiences and give his analysis of the state of German technology based on what his team uncovered at the end of the war and the extensive test flying of captured German aircraft which he performed both in Germany and later in the UK. He will include jet and rocket aircraft, also Blohm & Voss Bv 138,Bv 141 and Bv 222, wind tunnels and certain equipment such as ejection seats and “Schräge Musik” weapon installation. Captain Eric Brown had a 31 year career in the Royal Navy. After a distinguished operational tour flying from Britain’s first escort carrier, he was selected as a test pilot in 1942 and then served at A&AEE Boscombe Down before being appointed Chief Naval Test Pilot at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, where he remained for six years. -

Captain Eric (Winkle) Brown Cbe Dsc Afc Rn 1919 - 2016

CAPTAIN ERIC (WINKLE) BROWN CBE DSC AFC RN 1919 - 2016 It is with deep regret that the passing of Captain Eric Melrose Brown CBE DSC AFC is announced. Eric was the most decorated pilot of the Fleet Air Arm in which service he was universally known as ‘Winkle’ on account of his diminutive stature. He also held three absolute Guinness World Records, including for the number of aircraft carrier deck landings and types of aeroplane flown. He was born in Leith, Scotland on 21 January 1919 and educated at Fettes College and the University of Edinburgh, where he learned to fly in the University Air Squadron. His early flying experiences were with his father, a member of the Royal Flying Corps during the First World War and later Air Attaché in Berlin. During trips to Berlin as a student, Eric Brown witnessed the 1936 Olympic Games and the first indoor helicopter flights by Hanna Reitsch, Germany’s greatest female aviator, with whom he corresponded until her death in 1979. Germany was to figure in Eric Brown’s life for the next 75 years. He was a fluent speaker from time in the Third Reich as a language student, where, at one stage, he was arrested by the SS and deported. To earn money for his studies, Eric Brown became a ‘wall of death’ rider on a small 250cc two- stroke motorbike, often sharing the wall with his boss and a fully-grown male lion riding pillion. His flying skills were to send him to fly fighters from the world’s smallest aircraft carrier, HMS Audacity where he survived the ship being sunk by U-Boat on 21 December 1941. -

Schnellflug- Und Pfeilflügeltechnik

Der weitere Rundgang in der Halle 2 - die Schnellflugausstellung und die Geschichte der aerodynamischen Pfeilflügeltechnik mit der durch sie veränderten Welt Bevor wir Sie weiter durch unsere Ausstellung führen, wollen wir Sie ein wenig über die Hintergründe unserer Arbeit vertraut machen. Wir benötigen dafür Fachwissen mit breitem Hintergrund, und das müssen wir zusammen- tragen. Im Lauf der letzten 25 Jahre ist das eine stattliche Menge geworden und wird in unserem Archiv in einem Nebengebäude bearbeitet und verwaltet. Selbstverständlich müssen schon Grundkenntnisse durch eine längere Beschäftigung mit diesem komplexen Thema vorhanden sein, seien es technische, historische oder noch andere Zugänge. Unser Archiv: Oben links die Büchersammlung, rechts ebenso mit einem Teil der Flugzeug- Typensammlung, unten die Buchstaben A - D der Typensammlung in den A4-Ordnern. Doch kann man sich auch als Fachfremder gut darin einarbeiten, wenn man "zur Stange" hält. Wir alle sind als ehrenamtliche Mitarbeiter im Museumsteam keine studierten Museums- pädagogen oder sonstige Fachwissenschaftler, sondern Menschen aus allen möglichen Berufen, Handwerker und Juristen, Verwaltungsleute und Mediziner. Uns eint die Liebe zur Fliegerei, deren Technik und der Wille zur historischen Einordnung. Und ordentlich mit solchen Themen umzugehen, haben wir in anderen Berufen gelernt. Im Archivgebäude haben wir mehrere Räume, in denen einmal so um 4 - 5 tausend Bücher, diverse Luftfahrtzeitschriften und andere Periodika versammelt sind. Dazu kommt eine ausgedehnte Flugzeugtypensammlung, die sich aus Veröffentlichungen einheimischer und auswärtiger Luftfahrtzeitschriften über die letzen 60 - 70 Jahre speist, mit Motor-, Segel- und UL-Flugzeugen sowie Hubschraubern. Das sind noch einmal gute 800 A-4 Bände, Die verschiedenen Typen sind nach Herstellern alphabetisch sortiert. Dieses Archiv dürfen Sie nach tel.