Putting the Icosahedron Into the Octahedron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systematic Narcissism

Systematic Narcissism Wendy W. Fok University of Houston Systematic Narcissism is a hybridization through the notion of the plane- tary grid system and the symmetry of narcissism. The installation is based on the obsession of the physical reflection of the object/subject relation- ship, created by the idea of man-made versus planetary projected planes (grids) which humans have made onto the earth. ie: Pierre Charles L’Enfant plan 1791 of the golden section projected onto Washington DC. The fostered form is found based on a triacontahedron primitive and devel- oped according to the primitive angles. Every angle has an increment of 0.25m and is based on a system of derivatives. As indicated, the geometry of the world (or the globe) is based off the planetary grid system, which, according to Bethe Hagens and William S. Becker is a hexakis icosahedron grid system. The formal mathematical aspects of the installation are cre- ated by the offset of that geometric form. The base of the planetary grid and the narcissus reflection of the modular pieces intersect the geometry of the interfacing modular that structures the installation BACKGROUND: Poetics: Narcissism is a fixation with oneself. The Greek myth of Narcissus depicted a prince who sat by a reflective pond for days, self-absorbed by his own beauty. Mathematics: In 1978, Professors William Becker and Bethe Hagens extended the Russian model, inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, into a grid based on the rhombic triacontahedron, the dual of the icosidodeca- heron Archimedean solid. The triacontahedron has 30 diamond-shaped faces, and possesses the combined vertices of the icosahedron and the dodecahedron. -

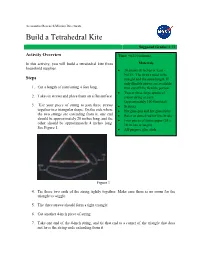

Build a Tetrahedral Kite

Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate Build a Tetrahedral Kite Suggested Grades: 8-12 Activity Overview Time: 90-120 minutes In this activity, you will build a tetrahedral kite from Materials household supplies. • 24 straws (8 inches or less) - NOTE: The straws need to be Steps straight and the same length. If only flexible straws are available, 1. Cut a length of yarn/string 4 feet long. then cut off the flexible portion. • Two or three large spools of 2. Take six straws and place them on a flat surface. cotton string or yarn (approximately 100 feet total) 3. Use your piece of string to join three straws • Scissors together in a triangular shape. On the side where • Hot glue gun and hot glue sticks the two strings are extending from it, one end • Ruler or dowel rod for kite bridle should be approximately 20 inches long, and the • Four pieces of tissue paper (24 x other should be approximately 4 inches long. 18 inches or larger) See Figure 1. • All-purpose glue stick Figure 1 4. Tie these two ends of the string tightly together. Make sure there is no room for the triangle to wiggle. 5. The three straws should form a tight triangle. 6. Cut another 4-inch piece of string. 7. Take one end of the 4-inch string, and tie that end to a corner of the triangle that does not have the string ends extending from it. Figure 2. 8. Add two more straws onto the longest piece of string. 9. Next, take the string that holds the two additional straws and tie it to the end of one of the 4-inch strings to make another tight triangle. -

On the Archimedean Or Semiregular Polyhedra

ON THE ARCHIMEDEAN OR SEMIREGULAR POLYHEDRA Mark B. Villarino Depto. de Matem´atica, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San Jos´e, Costa Rica May 11, 2005 Abstract We prove that there are thirteen Archimedean/semiregular polyhedra by using Euler’s polyhedral formula. Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 RegularPolyhedra .............................. 2 1.2 Archimedean/semiregular polyhedra . ..... 2 2 Proof techniques 3 2.1 Euclid’s proof for regular polyhedra . ..... 3 2.2 Euler’s polyhedral formula for regular polyhedra . ......... 4 2.3 ProofsofArchimedes’theorem. .. 4 3 Three lemmas 5 3.1 Lemma1.................................... 5 3.2 Lemma2.................................... 6 3.3 Lemma3.................................... 7 4 Topological Proof of Archimedes’ theorem 8 arXiv:math/0505488v1 [math.GT] 24 May 2005 4.1 Case1: fivefacesmeetatavertex: r=5. .. 8 4.1.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 8 4.1.2 All faces have at least four sides: p1 > 4 .............. 9 4.2 Case2: fourfacesmeetatavertex: r=4 . .. 10 4.2.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 10 4.2.2 All faces have at least four sides: p1 > 4 .............. 11 4.3 Case3: threefacesmeetatavertes: r=3 . ... 11 4.3.1 At least one face is a triangle: p1 =3................ 11 4.3.2 All faces have at least four sides and one exactly four sides: p1 =4 6 p2 6 p3. 12 4.3.3 All faces have at least five sides and one exactly five sides: p1 =5 6 p2 6 p3 13 1 5 Summary of our results 13 6 Final remarks 14 1 Introduction 1.1 Regular Polyhedra A polyhedron may be intuitively conceived as a “solid figure” bounded by plane faces and straight line edges so arranged that every edge joins exactly two (no more, no less) vertices and is a common side of two faces. -

THE GEOMETRY of PYRAMIDS One of the More Interesting Solid

THE GEOMETRY OF PYRAMIDS One of the more interesting solid structures which has fascinated individuals for thousands of years going all the way back to the ancient Egyptians is the pyramid. It is a structure in which one takes a closed curve in the x-y plane and connects straight lines between every point on this curve and a fixed point P above the centroid of the curve. Classical pyramids such as the structures at Giza have square bases and lateral sides close in form to equilateral triangles. When the closed curve becomes a circle one obtains a cone and this cone becomes a cylindrical rod when point P is moved to infinity. It is our purpose here to discuss the properties of all N sided pyramids including their volume and surface area using only elementary calculus and geometry. Our starting point will be the following sketch- The base represents a regular N sided polygon with side length ‘a’ . The angle between neighboring radial lines r (shown in red) connecting the polygon vertices with its centroid is θ=2π/N. From this it follows, by the law of cosines, that the length r=a/sqrt[2(1- cos(θ))] . The area of the iscosolis triangle of sides r-a-r is- a a 2 a 2 1 cos( ) A r 2 T 2 4 4 (1 cos( ) From this we have that the area of the N sided polygon and hence the pyramid base will be- 2 2 1 cos( ) Na A N base 2 4 1 cos( ) N 2 It readily follows from this result that a square base N=4 has area Abase=a and a hexagon 2 base N=6 yields Abase= 3sqrt(3)a /2. -

Archimedean Solids

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2008 Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Anderson, Anna, "Archimedean Solids" (2008). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Jim Lewis, Advisor July 2008 2 Archimedean Solids A polygon is a simple, closed, planar figure with sides formed by joining line segments, where each line segment intersects exactly two others. If all of the sides have the same length and all of the angles are congruent, the polygon is called regular. The sum of the angles of a regular polygon with n sides, where n is 3 or more, is 180° x (n – 2) degrees. If a regular polygon were connected with other regular polygons in three dimensional space, a polyhedron could be created. In geometry, a polyhedron is a three- dimensional solid which consists of a collection of polygons joined at their edges. The word polyhedron is derived from the Greek word poly (many) and the Indo-European term hedron (seat). -

Shape Skeletons Creating Polyhedra with Straws

Shape Skeletons Creating Polyhedra with Straws Topics: 3-Dimensional Shapes, Regular Solids, Geometry Materials List Drinking straws or stir straws, cut in Use simple materials to investigate regular or advanced 3-dimensional shapes. half Fun to create, these shapes make wonderful showpieces and learning tools! Paperclips to use with the drinking Assembly straws or chenille 1. Choose which shape to construct. Note: the 4-sided tetrahedron, 8-sided stems to use with octahedron, and 20-sided icosahedron have triangular faces and will form sturdier the stir straws skeletal shapes. The 6-sided cube with square faces and the 12-sided Scissors dodecahedron with pentagonal faces will be less sturdy. See the Taking it Appropriate tool for Further section. cutting the wire in the chenille stems, Platonic Solids if used This activity can be used to teach: Common Core Math Tetrahedron Cube Octahedron Dodecahedron Icosahedron Standards: Angles and volume Polyhedron Faces Shape of Face Edges Vertices and measurement Tetrahedron 4 Triangles 6 4 (Measurement & Cube 6 Squares 12 8 Data, Grade 4, 5, 6, & Octahedron 8 Triangles 12 6 7; Grade 5, 3, 4, & 5) Dodecahedron 12 Pentagons 30 20 2-Dimensional and 3- Dimensional Shapes Icosahedron 20 Triangles 30 12 (Geometry, Grades 2- 12) 2. Use the table and images above to construct the selected shape by creating one or Problem Solving and more face shapes and then add straws or join shapes at each of the vertices: Reasoning a. For drinking straws and paperclips: Bend the (Mathematical paperclips so that the 2 loops form a “V” or “L” Practices Grades 2- shape as needed, widen the narrower loop and insert 12) one loop into the end of one straw half, and the other loop into another straw half. -

Rhombic Triacontahedron

Rhombic Triacontahedron Figure 1 Rhombic Triacontahedron. Vertex labels as used for the corresponding vertices of the 120 Polyhedron. COPYRIGHT 2007, Robert W. Gray Page 1 of 11 Encyclopedia Polyhedra: Last Revision: August 5, 2007 RHOMBIC TRIACONTAHEDRON Figure 2 Icosahedron (red) and Dodecahedron (yellow) define the rhombic Triacontahedron (green). Figure 3 “Long” (red) and “short” (yellow) face diagonals and vertices. COPYRIGHT 2007, Robert W. Gray Page 2 of 11 Encyclopedia Polyhedra: Last Revision: August 5, 2007 RHOMBIC TRIACONTAHEDRON Topology: Vertices = 32 Edges = 60 Faces = 30 diamonds Lengths: 15+ ϕ = 2 EL ≡ Edge length of rhombic Triacontahedron. ϕ + 2 EL = FDL ≅ 0.587 785 252 FDL 2ϕ 3 − ϕ = DVF ϕ 2 FDL ≡ Long face diagonal = DVF ≅ 1.236 067 977 DVF ϕ 2 = EL ≅ 1.701 301 617 EL 3 − ϕ 1 FDS ≡ Short face diagonal = FDL ≅ 0.618 033 989 FDL ϕ 2 = DVF ≅ 0.763 932 023 DVF ϕ 2 2 = EL ≅ 1.051 462 224 EL ϕ + 2 COPYRIGHT 2007, Robert W. Gray Page 3 of 11 Encyclopedia Polyhedra: Last Revision: August 5, 2007 RHOMBIC TRIACONTAHEDRON DFVL ≡ Center of face to vertex at the end of a long face diagonal 1 = FDL 2 1 = DVF ≅ 0.618 033 989 DVF ϕ 1 = EL ≅ 0.850 650 808 EL 3 − ϕ DFVS ≡ Center of face to vertex at the end of a short face diagonal 1 = FDL ≅ 0.309 016 994 FDL 2 ϕ 1 = DVF ≅ 0.381 966 011 DVF ϕ 2 1 = EL ≅ 0.525 731 112 EL ϕ + 2 ϕ + 2 DFE = FDL ≅ 0.293 892 626 FDL 4 ϕ ϕ + 2 = DVF ≅ 0.363 271 264 DVF 21()ϕ + 1 = EL 2 ϕ 3 − ϕ DVVL = FDL ≅ 0.951 056 516 FDL 2 = 3 − ϕ DVF ≅ 1.175 570 505 DVF = ϕ EL ≅ 1.618 033 988 EL COPYRIGHT 2007, Robert W. -

Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions

Section 11-4 Math 366 Lecture Notes Section 11.4 – Geometry in Three Dimensions Simple Closed Surfaces A simple closed surface has exactly one interior, no holes, and is hollow. A sphere is the set of all points at a given distance from a given point, the center . A sphere is a simple closed surface. A solid is a simple closed surface with all interior points. (see p. 726) A polyhedron is a simple closed surface made up of polygonal regions, or faces . The vertices of the polygonal regions are the vertices of the polyhedron, and the sides of each polygonal region are the edges of the polyhedron. (see p. 726-727) A prism is a polyhedron in which two congruent faces lie in parallel planes and the other faces are bounded by parallelograms. The parallel faces of a prism are the bases of the prism. A prism is usually names after its bases. The faces other than the bases are the lateral faces of a prism. A right prism is one in which the lateral faces are all bounded by rectangles. An oblique prism is one in which some of the lateral faces are not bounded by rectangles. To draw a prism: 1) Draw one of the bases. 2) Draw vertical segments of equal length from each vertex. 3) Connect the bottom endpoints to form the second base. Use dashed segments for edges that cannot be seen. A pyramid is a polyhedron determined by a polygon and a point not in the plane of the polygon. The pyramid consists of the triangular regions determined by the point and each pair of consecutive vertices of the polygon and the polygonal region determined by the polygon. -

VOLUME of POLYHEDRA USING a TETRAHEDRON BREAKUP We

VOLUME OF POLYHEDRA USING A TETRAHEDRON BREAKUP We have shown in an earlier note that any two dimensional polygon of N sides may be broken up into N-2 triangles T by drawing N-3 lines L connecting every second vertex. Thus the irregular pentagon shown has N=5,T=3, and L=2- With this information, one is at once led to the question-“ How can the volume of any polyhedron in 3D be determined using a set of smaller 3D volume elements”. These smaller 3D eelements are likely to be tetrahedra . This leads one to the conjecture that – A polyhedron with more four faces can have its volume represented by the sum of a certain number of sub-tetrahedra. The volume of any tetrahedron is given by the scalar triple product |V1xV2∙V3|/6, where the three Vs are vector representations of the three edges of the tetrahedron emanating from the same vertex. Here is a picture of one of these tetrahedra- Note that the base area of such a tetrahedron is given by |V1xV2]/2. When this area is multiplied by 1/3 of the height related to the third vector one finds the volume of any tetrahedron given by- x1 y1 z1 (V1xV2 ) V3 Abs Vol = x y z 6 6 2 2 2 x3 y3 z3 , where x,y, and z are the vector components. The next question which arises is how many tetrahedra are required to completely fill a polyhedron? We can arrive at an answer by looking at several different examples. Starting with one of the simplest examples consider the double-tetrahedron shown- It is clear that the entire volume can be generated by two equal volume tetrahedra whose vertexes are placed at [0,0,sqrt(2/3)] and [0,0,-sqrt(2/3)]. -

The Mars Pentad Time Pyramids the Quantum Space Time Fractal Harmonic Codex the Pentagonal Pyramid

The Mars Pentad Time Pyramids The Quantum Space Time Fractal Harmonic Codex The Pentagonal Pyramid Abstract: Early in this author’s labors while attempting to create the original Mars Pentad Time Pyramids document and pyramid drawings, a failure was experienced trying to develop a pentagonal pyramid with some form of tetrahedral geometry. This pentagonal pyramid is now approached again and refined to this tetrahedral criteria, creating tetrahedral angles in the pentagonal pyramid, and pentagonal [54] degree angles in the pentagon base for the pyramid. In the process another fine pentagonal pyramid was developed with pure pentagonal geometries using the value for ancient Egyptian Pyramid Pi = [22 / 7] = [aPi]. Also used is standard modern Pi and modern Phi in one of the two pyramids shown. Introduction: Achieved are two Pentagonal Pyramids: One creates tetrahedral angle [54 .735~] in the Side Angle {not the Side Face Angle}, using a novel height of the value of tetrahedral angle [19 .47122061] / by [5], and then the reverse tetrahedral angle is accomplished with the same tetrahedral [19 .47122061] angle value as the height, but “Harmonic Codexed” to [1 .947122061]! This achievement of using the second height mentioned, proves aspects of the Quantum Space Time Fractal Harmonic Codex. Also used is Height = [2], which replicates the [36] and [54] degree angles in the pentagon base to the Side Angles of the Pentagonal Pyramid. I have come to understand that there is not a “perfect” pentagonal pyramid. No matter what mathematical constants or geometry values used, there will be a slight factor of error inherent in the designs trying to attain tetrahedra. -

Binary Icosahedral Group and 600-Cell

Article Binary Icosahedral Group and 600-Cell Jihyun Choi and Jae-Hyouk Lee * Department of Mathematics, Ewha Womans University 52, Ewhayeodae-gil, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03760, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-3277-3346 Received: 10 July 2018; Accepted: 26 July 2018; Published: 7 August 2018 Abstract: In this article, we have an explicit description of the binary isosahedral group as a 600-cell. We introduce a method to construct binary polyhedral groups as a subset of quaternions H via spin map of SO(3). In addition, we show that the binary icosahedral group in H is the set of vertices of a 600-cell by applying the Coxeter–Dynkin diagram of H4. Keywords: binary polyhedral group; icosahedron; dodecahedron; 600-cell MSC: 52B10, 52B11, 52B15 1. Introduction The classification of finite subgroups in SLn(C) derives attention from various research areas in mathematics. Especially when n = 2, it is related to McKay correspondence and ADE singularity theory [1]. The list of finite subgroups of SL2(C) consists of cyclic groups (Zn), binary dihedral groups corresponded to the symmetry group of regular 2n-gons, and binary polyhedral groups related to regular polyhedra. These are related to the classification of regular polyhedrons known as Platonic solids. There are five platonic solids (tetrahedron, cubic, octahedron, dodecahedron, icosahedron), but, as a regular polyhedron and its dual polyhedron are associated with the same symmetry groups, there are only three binary polyhedral groups(binary tetrahedral group 2T, binary octahedral group 2O, binary icosahedral group 2I) related to regular polyhedrons. -

Pentagonal Pyramid

Chapter 9 Surfaces and Solids Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. Pyramids, Area, and 9.2 Volume Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. Pyramids, Area, and Volume The solids (space figures) shown in Figure 9.14 below are pyramids. In Figure 9.14(a), point A is noncoplanar with square base BCDE. In Figure 9.14(b), F is noncoplanar with its base, GHJ. (a) (b) Figure 9.14 3 Pyramids, Area, and Volume In each space pyramid, the noncoplanar point is joined to each vertex as well as each point of the base. A solid pyramid results when the noncoplanar point is joined both to points on the polygon as well as to points in its interior. Point A is known as the vertex or apex of the square pyramid; likewise, point F is the vertex or apex of the triangular pyramid. The pyramid of Figure 9.14(b) has four triangular faces; for this reason, it is called a tetrahedron. 4 Pyramids, Area, and Volume The pyramid in Figure 9.15 is a pentagonal pyramid. It has vertex K, pentagon LMNPQ for its base, and lateral edges and Although K is called the vertex of the pyramid, there are actually six vertices: K, L, M, N, P, and Q. Figure 9.15 The sides of the base and are base edges. 5 Pyramids, Area, and Volume All lateral faces of a pyramid are triangles; KLM is one of the five lateral faces of the pentagonal pyramid. Including base LMNPQ, this pyramid has a total of six faces. The altitude of the pyramid, of length h, is the line segment from the vertex K perpendicular to the plane of the base.