Shona Sculpture'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

Approval of Minutes: Election of Officers: Sarah

BAKER CITY PUBLIC ARTS COMMISSION APPROVED MINUTES July 9, 2019 ROLL CALL: The meeting was called to order at 5:40 p.m. Present were: Ann Mehaffy, Lynette Perry, Corrine Vetger, Kate Reid, Fred Warner, Jr., Robin Nudd and guest Dean Reganess. APPROVAL OF Lynette moved to approve the June minutes as presented. Corrine MINUTES: seconded the motion. Motion carried. ELECTION OF Ann questioned if she and Corrine could serve as co-chairs. Robin OFFICERS: would check into it and let them know at next meeting. SARAH FRY PROJECT Ann reported that the pieces were being stored in the basement at UPDATE: City Hall. Ann would check with Molly to see if she had heard back on timeline for repairs to brickwork at the Corner Brick building. ART ON LOAN: Corrine stated that she would reach out to Shawn. SHAWN PETERSON PROJECT UPDATE: VINYL WRAP Nothing new to report on the project with ODOT. UPDATE: OTHER BUSINESS: Dean Reganess was present and visited with group regarding his trade: stone masonry. Dean is a third generation stone mason and had recently relocated to Baker City. Dean announced that he wanted to offer his help in the community and discussed creating a large community stone sculpture that could be pinned together. Dean also discussed stone benches with an estimated cost of $1200/each. Dean mentioned that a film crew would be coming from San Antonio and thought the exposure might be good for Baker. Corrine questioned if Dean had ideas to help the Public Arts Commission raise funds for public art. Dean mentioned that he would be willing to create a mold/casting of something that depicted Baker and it could be recreated and sold to raise funds. -

Africa Digests the West: a Review of Modernism and the Influence of Patrons-Cum Brokers on the Style and Form of Southern Eastern and Central African Art

ISSN-L: 2223-9553, ISSN: 2223-9944 Part-I: Social Sciences and Humanities Vol. 4 No. 1 January 2013 AFRICA DIGESTS THE WEST: A REVIEW OF MODERNISM AND THE INFLUENCE OF PATRONS-CUM BROKERS ON THE STYLE AND FORM OF SOUTHERN EASTERN AND CENTRAL AFRICAN ART Phibion Kangai 1, Joseph George Mupondi 2 1Department of Teacher Education, University of Zimbabwe, 2Curriculum Studies Department, Great Zimbabwe University, ZIMBABWE. 1 [email protected] , 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Modern Africa Art did not appear from nowhere towards the end of the colonial era. It was a response to bombardment by foreign cultural forms. African art built itself through “bricolage” Modernism was designed to justify colonialism through the idea of progress, forcing the colonized to reject their past way of life. Vogel (1994) argues that because of Darwin’s theory of evolution and avant-garde ideology which rejected academic formulas of representation, colonialists forced restructuring of existing artistic practice in Africa. They introduced informal trainings and workshops. The workshop patrons-cum brokers did not teach the conventions of art. Philosophically the workshops’ purpose was to release the creative energies within Africans. This assumption was based on the Roseauian ideas integrated culture which is destroyed by the civilization process. Some workshop proponents discussed are Roman Desfosses, of colonial Belgian Congo, Skotness of Polly Street Johannesburg, McEwen National Art Gallery Salisbury and Bloemfield of Tengenenge. The entire workshop contributed to development of black art and the birth of genres like Township art, Zimbabwe stone sculpture and urban art etc. African art has the willingness to adopt new ideas and form; it has also long appreciation of innovation. -

Sculpture Northwest Nov/Dec 2015 Ssociation a Nside: I “Conversations” Why Do You Carve? Barbara Davidson Bill Weissinger Doug Wiltshire Victor Picou Culptors

Sculpture NorthWest Nov/Dec 2015 ssociation A nside: I “Conversations” Why Do You Carve? Barbara Davidson Bill Weissinger Doug Wiltshire Victor Picou culptors S Stone Carving Videos “Threshold” Public Art by: Brian Goldbloom tone S est W t Brian Goldbloom: orth ‘Threshold’ (Detail, one of four Vine Maple column wraps), 8 feet high and 14 N inches thick, Granite Sculpture NorthWest is published every two months by NWSSA, NorthWest Stone Sculptors Association, a In This Issue Washington State Non-Profit Professional Organization. Letter From The President ... 3 CONTACT P.O. Box 27364 • Seattle, WA 98165-1864 FAX: (206) 523-9280 Letter From The Editors ... 3 Website: www.nwssa.org General e-mail: [email protected] “Conversations”: Why Do We Carve? ... 4 NWSSA BOARD OFFICERS Carl Nelson, President, (425) 252-6812 Ken Barnes, Vice President, (206) 328-5888 Michael Yeaman, Treasurer, (360) 376-7004 Verena Schwippert, Secretary, (360) 435-8849 NWSSA BOARD Pat Barton, (425) 643-0756 Rick Johnson, (360) 379-9498 Ben Mefford, (425) 943-0215 Steve Sandry, (425) 830-1552 Doug Wiltshire, (503) 890-0749 PRODUCTION STAFF Penelope Crittenden, Co-editor, (541) 324-8375 Lane Tompkins, Co-editor, (360) 320-8597 Stone Carving Videos ... 6 DESIGNER AND PRINTER Nannette Davis of QIVU Graphics, (425) 485-5570 WEBMASTER Carl Nelson [email protected] 425-252-6812 Membership...................................................$45/yr. Subscription (only)........................................$30/yr. ‘Threshold’, Public Art by Brian Goldbloom ... 10 Please Note: Only full memberships at $45/yr. include voting privileges and discounted member rates at symposia and workshops. MISSION STATEMENT The purpose of the NWSSA’s Sculpture NorthWest Journal is to promote, educate, and inform about stone sculpture, and to share experiences in the appreciation and execution of stone sculpture. -

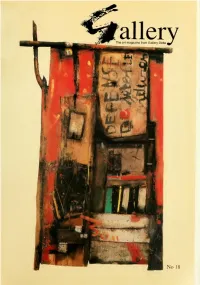

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine; ff^VoS SISIB Anglo American Corporation Services Limited T1HTO The Rio Tinto Foundation APEXAPEZCOBTCOBPOBATION OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht ^RISTON ^.Tanganda Tea Company Limited A-"^" * ETWORK •yvcoDBultaots NDORO Contents March 1997 Artnotes : the AICA conference on Art Criticism & Africa Burning fires or slumbering embers? : ceramics in Zimbabwe by Jack Bennett The perceptive eye and disciplined hand : Richard Witikani by Barbara Murray 11 Confronting complexity and contradiction : the 1996 Heritage Exhibition by Anthony Chennells 16 Painting the essence : the harmony and equilibrium of Thakor Patel by Barbara Murray 20 Reviews of recent work and forthcoming exhibitions and events including: Earth. Water, Fire: recent work by Berry Bickle, by Helen Lieros 10th Annual VAAB Exhibition, by Busani Bafana Explorations - Transformations, by Stanley Kurombo Robert Paul a book review by Anthony Chennells Cover: Tendai Gumbo, vessel, 1995, 25 x 20cm, terracotta, coiled and pit-fired (photo credit: Jack Bennett & Barbara Murray) Left: Crispen Matekenya, Baboon Chair, 1996, 160 x 1 10 x 80cm, wood © Gallery Publications Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Design & typesetting: Myrtle Mollis. Originaiion: HPP Studios. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Paper: Magno from Graphtec Lid. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta, the publisher or the editor Articles are invited for submission. -

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: APEX CDRPORATIDN OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht NDORO ^RISTON Contents December 1998 2 Artnotes 3 New forms for old : Dak" Art 1998 by Derek Huggins 10 Charting interior and exterior landscapes : Hilary Kashiri's recent paintings by Gillian Wright 16 'A Changed World" : the British Council's sculpture exhibition by Margaret Garlake 21 Anthills, moths, drawing by Toni Crabb 24 Fasoni Sibanda : a tribute 25 Forthcoming events and exhibitions Front Cover: TiehenaDagnogo, Mossi Km, 1997, 170 x 104cm, mixed media Back Cover: Tiebena Dagnogo. Porte Celeste, 1997, 156 x 85cm, mixed media Left: Tapfuma Gutsa. /// Winds. 1996-7, 160 x 50 x 62cm, serpentine, bone & horn © Gallery Publications ISSN 1361 - 1574 Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Designer: Myrtle Mallis. Origination: Crystal Graphics. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta. Gallery Publications, the publisher or the editor Articles and Letters are invited for submission. Please address them to The Editor Subscriptions from Gallery Publications, c/o Gallery Delta. 110 Livingstone Avenue, P.O. Box UA 373. Union Avenue, Harare. Zimbabwe. Tel & Fa.x: (263-4) 792135, e-mail: <[email protected]> Artnotes A surprising fact: Zimbabwean artworks are Hivos give support to many areas of And now, thanks to Hivos. -

Mashonaland Central Province : 2013 Harmonised Elections:Presidential Election Results

MASHONALAND CENTRAL PROVINCE : 2013 HARMONISED ELECTIONS:PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION RESULTS Mugabe Robert Mukwazhe Ncube Dabengwa Gabriel (ZANU Munodei Kisinoti Welshman Tsvangirayi Total Votes Ballot Papers Total Valid Votes District Local Authority Constituency Ward No. Polling Station Facility Dumiso (ZAPU) PF) (ZDP) (MDC) Morgan (MDC-T) Rejected Unaccounted for Total Votes Cast Cast Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 1 Bindura Primary Primary School 2 519 0 1 385 6 0 913 907 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 1 Bindura Hospital Tent 0 525 0 8 521 11 0 1065 1054 2 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 2 1,044 0 9 906 17 0 1,978 1,961 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 2 Bindura University New Site 0 183 2 1 86 2 0 274 272 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 2 Shashi Primary Primary School 0 84 0 2 60 2 0 148 146 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 2 Zimbabwe Open UniversityTent 2 286 1 4 166 5 0 464 459 3 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 2 553 3 7 312 9 0 886 877 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 3 Chipindura High Secondary School 2 80 0 0 81 1 2 164 163 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 3 DA’s Campus Tent 1 192 0 7 242 2 0 444 442 2 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 3 272 0 7 323 3 2 608 605 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 4 Salvation Army Primary School 1 447 0 7 387 12 0 854 842 1 POLLING STATIONS WARD TOTAL 1 447 0 7 387 12 0 854 842 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 5 Chipadze A Primary School ‘A’ 0 186 2 0 160 4 0 352 348 Bindura Bindura Municipality Bindura North 5 Chipadze B -

Structure and Meaning in the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe

STRUCTURE AND MEANING IN THE PREHISTORIC ART OF ZIMBABWE PETER S. GARLAKE Seventeenth Annual Mans Wolff Memorial Lecture April 15, 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana Copyright 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University All rights reserved ISBN 0-941934-51-9 PETER S. GARLAKE Peter S. Garlake is an archaeologist and the author of many books on Africa. He has conducted fieldwork in Somalia, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Qatar, the Comoro Islands and Mozambique, and has directed excavations at numerous sites in Zimbabwe. He was the Senior Inspector of Monuments in Rhodesia from 1964 to 1970, and a senior research fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ife from 1971 to 1973. From 1975 to 1981, he was a lecturer in African archaeology and material culture at the Department of Anthropology, University College, University of London. F.rom 1981 to 1985, he was attached to the Ministry of Education and Culture in Zimbabwe and in 1984-1985 was a lecturer in archaeology at the University of Zimbabwe. For the past year, he has been conducting full time research on the prehistoric rock art of Zimbabwe. He is the author of Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast, 1966; Great Zimbabwe, 1973; The Kingdoms of Africa, 1978; Great Zimbabwe Described and Exglained, 1982; Life qt Great Zimbabwe, 1982; People Making History, 1985; and is currently writing The Painted Caves. Peter Garlake is a contributor to the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archaeology, the hpggqn ---Encyclopedia --- ---- of Africa and the MacMillan Dictionary of big, and is the author of many journal and newspaper articles. -

Chapungu Sculpture Park

CHAPUNGU SCULPTURE PARK Do you Chapungu (CHA-poon-goo)? The real showcase within the Centerra community is the one-of-a-kind Chapungu Sculpture Park. Nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, this 26-acre outdoor cultural experience features more than 80 authentic stone sculptures carved by artisans from Zimbabwe displayed amongst beautiful natural and landscaped gardens. The entire walking park which is handicap accessible, orients visitors to eight universal themes, which include: Nature & Environment • Village Life • The Role of Women • The Elders • The Spirit World • The Family The Children • Custom & Legend. Whether you are an art enthusiast or just enjoy the outdoors, this serenity spot is worth checking out. Concrete and crushed rock used from the makings of the sculptures refine trails and lead you along the Greeley and Loveland Irrigation Canal and over bridges. Soak in the sounds of the birds perched high above in the cottonwood trees while resting on a park bench with a novel or newspaper in hand. Participate in Centerra’s annual summer concert series, enjoy a self guided tour, picnic in the park, or attend Visit Loveland’s Winter Wonderlights hosted F R E E A D M I S S I O N at the park and you are bound to have a great experience each time you visit. Tap Into Chapungu Park Hours: Daily from 6 A.M. to 10:30 P.M. Easily navigate all the different Chapungu Sculpture Park is conveniently located just east of the Promenade Shops at Centerra off Hwy. 34 and regions within Chapungu Located east of the Promenade Shops Centerra Parkway in Loveland, Colorado. -

Culture and Customs of Zimbabwe 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page Ii

6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page i Culture and Customs of Zimbabwe 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page ii Recent Titles in Culture and Customs of Africa Culture and Customs of Nigeria Toyin Falola Culture and Customs of Somalia Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi Culture and Customs of the Congo Tshilemalema Mukenge Culture and Customs of Ghana Steven J. Salm and Toyin Falola Culture and Customs of Egypt Molefi Kete Asante 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page iii Culture and Customs of Zimbabwe Oyekan Owomoyela Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London 6596D FM UG 9/20/02 5:33 PM Page iv Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Owomoyela, Oyekan. Culture and customs of Zimbabwe / Oyekan Owomoyela. p. cm.—(Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–31583–3 (alk. paper) 1. Zimbabwe—Social life and customs. 2. Zimbabwe—Civilization. I. Title. II. Series. DT2908.O86 2002 968.91—dc21 2001055647 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2002 by Oyekan Owomoyela All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2001055647 ISBN: 0–313–31583–3 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). -

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 Through October 31, 2007 ABOUT the ARTISTS

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 through October 31, 2007 ABOUT THE ARTISTS Dominic Benhura, b. 1968 in Murewa – “Who Is Strongest?”, “Zimbabwe Bird” At age 10 Benhura began to assist his cousin, sculptor Tapfuma Gutsa, spending many formative years at Chapungu Sculpture Park. Soon after he began to create his own works. Today he is regarded as the cutting edge of Zimbabwe sculpture. His extensive subject matter includes plants, trees, reptiles, animals and the gamut of human experience. Benhura has an exceptional ability to portray human feeling through form rather than facial expression. He leads by experimentation and innovation. Ephraim Chaurika, b. 1940 in Zimbabwe – “Horse” Before joining the Tengenenge Sculpture Community in 1966, Chaurika was a herdsman and a local watchmaker. He engraved the shape of watch springs and cog wheels in some of his early sculptures. His early works were often large and powerfully expressive, sometimes using geometric forms, while later works are more whimsical and stylistic. His sculptures are always skillful, superbly finished and immediately appealing. Sanwell Chirume, b. 1940 in Guruve – “Big Buck Surrendering” Chirume is a prominent Tengenenge artist and a relative of artist Bernard Matemura. He first visited Tengenenge in 1971 to help quarry stone. In 1976 he returned to become a full time sculptor. Largely unacknowledged, he nevertheless creates powerful large sculptures of considerable depth. His work has been in many major exhibitions, has won numerous awards in the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, and is featured in the Chapungu Sculpture Park’s permanent collection. Edward Chiwawa, b. 1935 northwest of Guruve – “Lake Bird” This first generation master sculptor learned to sculpt by working with his cousin, Henry Munyaradzi. -

Sculpture and Inscriptions from the Monumental Entrance to the Palatial Complex at Kerkenes DAĞ, Turkey Oi.Uchicago.Edu Ii

oi.uchicago.edu i KERKENES SPECIAL STUDIES 1 SCULPTURE AND INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE MONUMENTAL ENTRANCE TO THE PALATIAL COMPLEX AT KERKENES DAĞ, TURKEY oi.uchicago.edu ii Overlooking the Ancient City on the Kerkenes Dağ from the Northwest. The Palatial Complex is Located at the Center of the Horizon Just to the Right of the Kale oi.uchicago.edu iii KERKENES SPECIAL STUDIES 1 SCULPTURE AND INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE MONUMENTAL ENTRANCE TO THE PALATIAL COMPLEX AT KERKENES DAĞ, TURKEY by CatheRiNe M. DRAyCOTT and GeOffRey D. SuMMeRS with contribution by CLAUDE BRIXHE and Turkish summary translated by G. B∫KE YAZICIO˝LU ORieNTAL iNSTiTuTe PuBLiCATiONS • VOLuMe 135 THe ORieNTAL iNSTiTuTe Of THe uNiVeRSiTy Of CHiCAGO oi.uchicago.edu iv Library of Congress Control Number: 2008926243 iSBN-10: 1-885923-57-0 iSBN-13: 978-1-885923-57-8 iSSN: 0069-3367 The Oriental Institute, Chicago ©2008 by The university of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2008. Printed in the united States of America. ORiental iNSTiTuTe PuBLicatiONS, VOLuMe 135 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. urban with the assistance of Katie L. Johnson Series Editors’ Acknowledgments The assistance of Sabahat Adil, Melissa Bilal, and Scott Branting is acknowledged in the production of this volume. Spine Illustration fragment of a Griffin’s Head (Cat. No. 3.6) Printed by Edwards Brothers, Ann Arbor, Michigan The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for information Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSi Z39.48-1984. oi.uchicago.edu v TABLE OF CONTENTS LiST Of ABBReViatiONS ............................................................................................................................