The Nature of Orthographic-Phonological And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Orthographic Systems on the Developing Reading System: Typological and Computational Analyses

Psychological Review © 2020 American Psychological Association 2021, Vol. 128, No. 1, 125–159 ISSN: 0033-295X http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/rev0000257 The Effect of Orthographic Systems on the Developing Reading System: Typological and Computational Analyses Alastair C. Smith Padraic Monaghan Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics Lancaster University Falk Huettig Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics and Radboud University Orthographic systems vary dramatically in the extent to which they encode a language’s phonological and lexico-semantic structure. Studies of the effects of orthographic transparency suggest that such variation is likely to have major implications for how the reading system operates. However, such studies have been unable to examine in isolation the contributory effect of transparency on reading because of covarying linguistic or sociocultural factors. We first investigated the phonological properties of languages using the range of the world’s orthographic systems (alphabetic, alphasyllabic, consonantal, syllabic, and logographic), and found that, once geographical proximity is taken into account, phono- logical properties do not relate to orthographic system. We then explored the processing implications of orthographic variation by training a connectionist implementation of the triangle model of reading on the range of orthographic systems while controlling for phonological and semantic structure. We show that the triangle model is effective as a universal model of reading, able to replicate key behavioral and -

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

7$0,/³(1*/,6+ ',&7,21$5< COMMON SPOKEN TAMIL MADE EASY

7$0,/³(1*/,6+ ',&7,21$5< )RU8VH:LWK &20021632.(17$0,/ 0$'(($6< 7KLUG(GLWLRQ E\ 79$',.(6$9$/8 'LJLWDO9HUVLRQ &+5,67,$10(',&$/&2//(*(9(//25( Adi’s Book, Tamil-English Dictionary. KEY adv. adverb n. noun pron. pronoun v. verb nom. takes nominatve case dat. takes dative case adj. adjective acc. takes accusative case d.b. taked declensional base intr. intransitive tr. transitive neut. neuter imp. impersonal pers. personal incl inclusive excl. exclusive m. masculine f. feminine sing. singular pl. plural w. weak s. strong TAMIL ENGLISH TAMIL ENGLISH KX ZQ become, happen DNN sister (older) KX ZQ happen, become DNNXº arm pit DE\VDP exercise (n.) DºD VQGK measure DE\VDPVHL ZGK exercise (v.) alamaram banyan tree adangu (w.in) obey DºDYXHGX VWKWK measurements (take m.) adangu (w.in) subside alladhu or adhan its P yes DGKDQOHKDL\OH therefore DPYVH no moon DGK same ambadhu fifty DGKLKUDP authority DPP madam DGKLNODLOH early morning DPPWK\U mother adhisayam wonder (n.) ammi grindstone adhu it ¼ male adhu (pron. neut.) that Q but DGKXNNXWKKXQGKSÀOD accordingly anai dam adhunga their (neut.) DQVLDQFKL pine apple adhunga they (things) DQEXQVDP love, kindness adhunga those (things)(are) QGDYDU Lord DGKXQJDºH them (things) andha (adj) that adi (s.thth) strike andha (pron.neut.) those adikkadi often DQKD many GX goat, sheep DQKDP almost, mostly aduppu oven, stove ange there aduththa next DQJHGKQ there only ahalam width anju five ahappadu (w.tt) caught, (to be) found D¼¼DQ brother (elder) DK\DYLPQDP aeroplane anumadhi permission (n.) K\DPYQXP sky anumadhi permit (n.) LSÀFKFKX FRO finished anumadhi kodu (s.thth) permit (v.) DLQQÌUX five hundred anuppu (w.in) send LSÀ ZQ exhaust, finish apdi that way DL\ sir DSGLGKQ that is it DL\À oh dear DSGL\ indeed?, is that so? DL\ÀSYDP poor soul! DSGL\" really?, right? DNN elder sister DSSWKDKDSSDQ father Adi’s Book, Tamil-English Dictionary. -

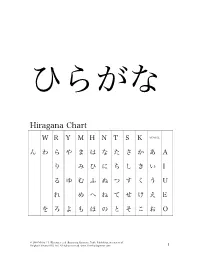

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Shallow Vs Non-Shallow Orthographies and Learning to Read Workshop 28-29 September 2005

A Report of the OECD-CERI LEARNING SCIENCES AND BRAIN RESEARCH Shallow vs Non-shallow Orthographies and Learning to Read Workshop 28-29 September 2005 St. John’s College Cambridge University UK Co-hosted by The Centre for Neuroscience in Education Cambridge University Report prepared by Cassandra Davis OECD, Learning Sciences and Brain Research Project 1 Background information The goal of this report of this workshop is to: • Provide an overview of the content of the workshop presentations. • Present a summary of the discussion on cross-language differences in learning to read and the future of brain science research in this arena. N.B. The project on "Learning Sciences and Brain Research" was introduced to the OECD's CERI Governing Board on 23 November 1999, outlining proposed work for the future. The purpose of this novel project was to create collaboration between the learning sciences and brain research on the one hand, and researchers and policy makers on the other hand. The CERI Governing Board recognised this as a risk venture, as most innovative programmes are, but with a high potential pay-off. The CERI Secretariat and Governing Board agreed in particular that the project had excellent potential for better understanding learning processes over the lifecycle, but that ethical questions also existed. Together these potentials and concerns highlighted the need for dialogue between the different stakeholders. The project is now in its second phase (2002- 2005), and has channelled its activities into 3 networks (literacy, numeracy and lifelong learning) using a three dimensional approach: problem-focused; trans-disciplinary; and international. -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau. -

KANA Response Live Organization Administration Tool Guide

This is the most recent version of this document provided by KANA Software, Inc. to Genesys, for the version of the KANA software products licensed for use with the Genesys eServices (Multimedia) products. Click here to access this document. KANA Response Live Organization Administration KANA Response Live Version 10 R2 February 2008 KANA Response Live Organization Administration All contents of this documentation are the property of KANA Software, Inc. (“KANA”) (and if relevant its third party licensors) and protected by United States and international copyright laws. All Rights Reserved. © 2008 KANA Software, Inc. Terms of Use: This software and documentation are provided solely pursuant to the terms of a license agreement between the user and KANA (the “Agreement”) and any use in violation of, or not pursuant to any such Agreement shall be deemed copyright infringement and a violation of KANA's rights in the software and documentation and the user consents to KANA's obtaining of injunctive relief precluding any further such use. KANA assumes no responsibility for any damage that may occur either directly or indirectly, or any consequential damages that may result from the use of this documentation or any KANA software product except as expressly provided in the Agreement, any use hereunder is on an as-is basis, without warranty of any kind, including without limitation the warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement. Use, duplication, or disclosure by licensee of any materials provided by KANA is subject to restrictions as set forth in the Agreement. Information contained in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of KANA. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text. -

Basis Technology Unicode対応ライブラリ スペックシート 文字コード その他の名称 Adobe-Standard-Encoding A

Basis Technology Unicode対応ライブラリ スペックシート 文字コード その他の名称 Adobe-Standard-Encoding Adobe-Symbol-Encoding csHPPSMath Adobe-Zapf-Dingbats-Encoding csZapfDingbats Arabic ISO-8859-6, csISOLatinArabic, iso-ir-127, ECMA-114, ASMO-708 ASCII US-ASCII, ANSI_X3.4-1968, iso-ir-6, ANSI_X3.4-1986, ISO646-US, us, IBM367, csASCI big-endian ISO-10646-UCS-2, BigEndian, 68k, PowerPC, Mac, Macintosh Big5 csBig5, cn-big5, x-x-big5 Big5Plus Big5+, csBig5Plus BMP ISO-10646-UCS-2, BMPstring CCSID-1027 csCCSID1027, IBM1027 CCSID-1047 csCCSID1047, IBM1047 CCSID-290 csCCSID290, CCSID290, IBM290 CCSID-300 csCCSID300, CCSID300, IBM300 CCSID-930 csCCSID930, CCSID930, IBM930 CCSID-935 csCCSID935, CCSID935, IBM935 CCSID-937 csCCSID937, CCSID937, IBM937 CCSID-939 csCCSID939, CCSID939, IBM939 CCSID-942 csCCSID942, CCSID942, IBM942 ChineseAutoDetect csChineseAutoDetect: Candidate encodings: GB2312, Big5, GB18030, UTF32:UTF8, UCS2, UTF32 EUC-H, csCNS11643EUC, EUC-TW, TW-EUC, H-EUC, CNS-11643-1992, EUC-H-1992, csCNS11643-1992-EUC, EUC-TW-1992, CNS-11643 TW-EUC-1992, H-EUC-1992 CNS-11643-1986 EUC-H-1986, csCNS11643_1986_EUC, EUC-TW-1986, TW-EUC-1986, H-EUC-1986 CP10000 csCP10000, windows-10000 CP10001 csCP10001, windows-10001 CP10002 csCP10002, windows-10002 CP10003 csCP10003, windows-10003 CP10004 csCP10004, windows-10004 CP10005 csCP10005, windows-10005 CP10006 csCP10006, windows-10006 CP10007 csCP10007, windows-10007 CP10008 csCP10008, windows-10008 CP10010 csCP10010, windows-10010 CP10017 csCP10017, windows-10017 CP10029 csCP10029, windows-10029 CP10079 csCP10079, windows-10079