EASTERN Buddillst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

Studies in Central & East Asian Religions Volume 9 1996

Studies in Central & East Asian Religions Volume 9 1996 CONTENTS Articles Xu WENKAN: The Tokharians and Buddhism……………………………………………... 1 Peter SCHWEIGER: Schwarze Magie im tibetischen Buddhismus…………………….… 18 Franz-Karl EHRHARD: Political and Ritual Aspects of the Search for Himalayan Sacred Lands………………………………………………………………………………. 37 Gabrielle GOLDFUβ: Binding Sūtras and Modernity: The Life and Times of the Chinese Layman Yang Wenhui (1837–1911)………………………………………………. 54 Review Article Hubert DECLEER: Tibetan “Musical Offerings” (Mchod-rol): The Indispensable Guide... 75 Forum Lucia DOLCE: Esoteric Patterns in Nichiren’s Thought…………………………………. 89 Boudewijn WALRAVEN: The Rediscovery of Uisang’s Ch’udonggi…………………… 95 Per K. SØRENSEN: The Classification and Depositing of Books and Scriptures Kept in the National Library of Bhutan……………………………………………………….. 98 Henrik H. SØRENSEN: Seminar on the Zhiyi’s Mohe zhiguan in Leiden……………… 104 Reviews Schuyler Jones: Tibetan Nomads: Environment, Pastoral Economy and Material Culture (Per K. Sørensen)…………………………………………………………………. 106 [Ngag-dbang skal-ldan rgya-mtsho:] Shel dkar chos ’byung. History of the “White Crystal”. Religion and Politics of Southern La-stod. Translated by Pasang Wangdu and Hildegard Diemberger (Per K. Sørensen)………………………………………… 108 Blondeau, Anne-Marie and Steinkellner, Ernst (eds.): Reflections of the Mountains. Essays on the History and Social Meaning of the Cult in Tibet and the Himalayas (Per K. Sørensen)…………………………………………………………………………. 110 Wisdom of Buddha: The Saṃdhinirmocana Mahāyāna Sūtra (Essential Questions and Direct Answers for Realizing Enlightenment). Transl. by John Powers (Henrik H. Sørensen)………………………………………………. 112 Japanese Popular Deities in Prints and Paintings: A Catalogue of the Exhibition (Henrik H. Sørensen)…………………………………………………………………………. 113 Stephen F. Teiser, The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism (Henrik H. -

Wisdom of Buddha

Wisdom of Buddha The Samdhinirmocana Sutra Translated by John Powers Dharma Publishing TIBETAN TRANSLATION SERIES 1. Calm and Clear 2. The Legend of the Great Stupa 3. Mind in Buddhist Psychology 4. Golden Zephyr (Nāgārjuna) 5. Kindly Bent to Ease Us, Parts 1-3 6. Elegant Sayings (Nāgārjuna, Sakya Pandita) 7. The Life and Liberation ofPadmasambhava 8. Buddha's Lions: Lives of the 84 Siddhas 9. The Voice of the Buddha (Lalitavistara Sūtra) 10. The Marvelous Companion (Jātakamālā) 11. Mother of Knowledge: Enlightenment ofYeshe Tshogyal 12. The Dhammapada (Teachings on 26 Topics) 13. The Fortunate Aeon (Bhadrakalpika Sūtra) 14. Master of Wisdom (Nāgārjuna) 15. Joy for the World (Candrakīrti) 16. Wisdom of Buddha (Samdhinirmocana Sūtra) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tripkaka. Samdhini^mocanasūt^a. English Wisdom of Buddha : the Samdhinirmocana Sūtra / translated by John Powers. p. cm. - (Tibetan translation series.) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-89800-247-8. - ISBN 0-89800-246-X (pbk.) I. Title. II. Series BQ2092.E5 1994 294.3'85-dc20 94-25023 CIP Copyright ©1995 by Dharma Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this book, including text, art, reproductions, and illustrations, may be copied, reproduced, published, or stored electronically, photo- graphically, or optically in any form without the express written consent of Dharma Publishing, 2425 Hillside Avenue, Berkeley, CA 94704 USA Frontispiece: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Gift of Joseph H. Heil, 1970 (1970.298.1) This publication -

O Budismo Yogacara: História, Literatura E Doutrina

O budismo Yogacara: história, literatura e doutrina Yogacara buddhism: history, literature and doctrine Nestor Figueiredo* Resumo O objetivo deste trabalho é apresentar o contexto histórico de emergência da escola Yogacara, a partir de sua formulação inicial dentro da tradição budista Mahayna na Índia e seus textos clássicos de fundação, abordando sumariamente as questões teóricas centrais propostas por essa linha filosófica, recuperando uma análise de parte dessas ideias e estabelecendo considerações de caráter geral com base nesse percurso. Na seção final, trataremos da principal temática em disputa envolvendo estudiosos nessa área. Metodologicamente, portanto, será um texto predominantemente descritivo, sem pretensão analítica, em que procuraremos sintetizar acontecimentos e aspectos teóricos fundamentais relacionados a esta forma de pensamento centrado na mente, partindo de algumas obras relevantes sobre o budismo Yogacara. Palavras-chave: Yogacara. Budismo. Mente. Consciência. Idealismo. Abstract The aim of this paper is to present the historical context of emergence of the Yogacara school, from its initial formulation within the Mahayna Buddhist tradition in India and its classical texts of foundation, briefly comprising the central theoretical questions proposed by this philosophical line, retrieving an analysis of some of these ideas and establishing general considerations based on this path. In the final section, we will deal with the main issue in dispute involving scholars in this area. Therefore, methodologically speaking, it will be a predominantly descriptive text, without analytical pretension, in which we will try to synthesize events and fundamental theoretical aspects related to this mind-centered form of thinking, from some relevant works on Yogacara Buddhism. Keywords: Yogacara. Buddhism. Mind. Consciousness. Idealism. -

On a Recent Translation of the Saṃdhinirmocanasūtra

INST1TUT FUR TIBETOLOGIE UNO BUDOHISMUSKUNOE UNIVERSITATSCAMPUS AAKH, HOF 2 SPITALQASSE 2-4, A-1090 WIEN AUSTRIA, EUROPE Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 20 • Number 1 • Summer 1997 PAUL L. SWANSON Whaf s Going on Here? Chih-i's Use (and Abuse) of Scripture 1 GEORGES DREYFUS Tibetan Scholastic Education and The Role of Soteriology 31 ANDREW HUXLEY Studying Theravada Legal Literature 63 PETER SKILLING The Advent of Theravada Buddhism to Mainland South-east Asia 93 ELI FRANCO Distortion as a Price for Comprehensibility? The rGyal tshab-Jackson Interpretation of Dharmakirti 109 ROGER R. JACKSON 'The Whole Secret Lies in Arbitrariness": A Reply to Eli Franco 133 ELI FRANCO A Short Response to Roger Jackson's Reply TOM J. F. TILLEMANS On a Recent Translation of the Samdhinirmocanasiitra JOHN R. MCRAE Review: Zenbase CD1 JOE BRANSFORD WILSON The International Association of Buddhist Studies and the World Wide Web TOM J. F. TILLEMANS On a Recent Translation of the Samdhinirmocanasutra Wisdom of Buddha. The Samdhinirmocana Sutra. Translated by John Powers. Tibetan Translation Series 16. Berkeley CA: Dharma Publishing, 1995. Xxii and 397 pages, 14 illustrations and line drawings. Following the traditional explanation by Mahayanist schools, Buddhist sutras are classified according to three cycles (dharmacakrapravartana). The first consists in the texts of the so-called "Small Vehicle" (hinayana), which supposedly taught the non-existence of a real personal identity, reducing it to real elements {dharma). The second was the voluminous collection of the Prajnaparamitdsutras, which were said to have taught the idea of the unreality of persons as well as that of the elements, i. -

Studies in the Lankavatara Sutra, Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Pp

READING THE WORDS OF THE BUDDHA ~ THE PROFOUND AND VAST MAHAYANA SUTRAS ~ SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS SOURCEBOOK For internal use only Exclusively for the use of the Rime Shedra NYC Core Texts Program A program of Shambhala Meditation Center of New York First Edition Reading the Words of the Buddha The Profundity and Vastness of the Mahayana Sutras Ten Tuesdays, 7‐9:15 pm, September 25th to December 11th SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS SOURCEBOOK I. Introduction to the Profound and Vast Teachings of the Buddha A. The Wheels of The Dharma, from The Treasury of Knowledge 2, 3, 4 Buddhism's Journey to Tibet, Jamgon Kongtrul, Translated by Ngawang Zangpo, pp. 150‐156 B. Major Scriptures, excerpt from Mahayana Buddhism, by Hajime Nakamura, in Buddhism and Asian History, pp. 222‐229 C. The Contents of Early Mahayana Scriptures, from A History of Indian Buddhism, by Hirakawa Akira, pp. 275‐295 II. The Vajracchedika Prajnaparamita Sutra – The Perfection of Diamond Is No Perfection A. The Perfection of Wisdom in the Vajracchedika‐sutra, from HBP, David Kalupahana, pp. 153‐159 B. The Story of Ever Weeping, in On Indian Mahayana Buddhism, by D. T. Suzuki, pp. 101‐ 108 C. The Prajnaparamita Literature, Lewis Lancaster, from BMP, pp. 69‐71 D. Astasahasrika Sutra, Karl Potter, from EIP, pp. 79‐86 E. Introduction, The Large Sutra On Perfect Wisdom with the Divisions of the Abhisamayālañkāra, Translated by Edward Conze, pp. 37‐44 III. Kashyapa Parivarta Sutra – The Interrogation by the Bodhisattva Kashyapa A. The Middle Path According to the Kasyapaparivarta‐sutra, Leslie Kawamura, from Wisdom, Compassion and the Search for Understanding, Ed. -

Reading List for the Study of the Sandhinirmocana Sutra

Reading List for the Study of the Sandhinirmocana Sutra SANDHINIRMOCANA SUTRA: Wisdom of Buddha, The Samdhinirmocana Mahayana Sutra, Essential Questions and Direct Answers for Realizing Enlightenment, Translated from the Tibetan by John Powers, Dharma Publishing, 1994 The Scripture on the Explication of Underlying Meaning, Translated from the Chinese of Hsuan-tsang, Translated by John P. Keenan, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 2000 (Taisho volume 16, Number 676) Buddhist Yoga, A Comprehensive Course, Translated by Thomas Cleary, Shambhala, 1995 COMMENTARIES: Two Commentaries on the Samdhinirmocana Sutra by Asanga and Jnanagarbha, Translated by John Powers, Edwin Mellen Press, 1992 Jnanagarbha’s Commentary on Just the Maitreya Chapter From the Samdhinirmocana Sutra, Study, Translation and Tibetan Text, Translated by John Powers, Indian Council of Philosophical Research, New Delhi, 1998 Emptiness in the Mind-Only School of Buddhism, Dynamic Responses to Dzong-ka-ba’s ‘The Essence of Eloquence: 1’, Jeffrey Hopkins, University of California Press, 1999 Reflections On Reality: The Three Natures and Non-Natures in the Mind-Only School, Jeffrey Hopkins, University of California Press, 2002 The Summary of the Great Vehicle by the Bodhisattva Asanga, Translated by John P. Keenan, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 1992 (Taisho volume 31, Number 1593) The Central Philosophy of Tibet – A Study and Translation of Jey Tsong Khapa’s ‘Essence of True Eloquence’, Robert Thurman, Princeton University Press, 1991 Empty Words, Buddhist Philosophy and Cross-cultural Interpretation. Jay L. Garfield, Oxford Press, 2002 TRIMSHIKA VIJNAPTI MATRATA SIDDHI, by Vashubandu Principles of Buddhist Psychology, Vijnaptimatratasiddhi Vimsatika and Trimsika, David Kalupahana The Seven Works of Vashubandu,, The Thirty Verses, Hsuan Tsang trans. -

Abhisamayalamkara the Ornament of Higher Realization by Maitreya ~ an Introduction

ABHISAMAYALAMKARA THE ORNAMENT OF HIGHER REALIZATION BY MAITREYA ~ AN INTRODUCTION SOURCE BOOK RIME SHEDRA NYC SMCNY ADVANCED BUDDHIST STUDIES CHANTS ASPIRATION In order that all sentient beings may attain Buddhahood, From my heart I take refuge in the three jewels. This was composed by Mipham. Translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee MANJUSHRI SUPPLICATION Whatever the virtues of the many fields of knowledge All are steps on the path of omniscience. May these arise in the clear mirror of intellect. O Manjushri, please accomplish this. This was specially composed by Mangala (Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche). Translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee DEDICATION OF MERIT By this merit may all obtain omniscience May it defeat the enemy, wrong doing. From the stormy waves of birth, old age, sickness and death, From the ocean of samsara, may I free all beings By the confidence of the golden sun of the great east May the lotus garden of the Rigden’s wisdom bloom, May the dark ignorance of sentient beings be dispelled. May all beings enjoy profound, brilliant glory. Translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee For internal use only Exclusively for the Rime Shedra NYC Core Texts Program A program of Shambhala Meditation Center of New York First Edition – 2014 THE ABHISAMAYALAMKARA THE ORNAMENT OF HIGHER REALIZATION BY MAITREYA AN INTRODUCTION Who Knows What, Where, When, and How SOURCEBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Syllabus 2. Outline of the Chapters of the Abhisamayalamkara 3. The 70 Points of the Abhisamayalamkara from Edward Conze 4. A Detailed Outline of the Abhisamayalamkara by Thrangu Rinpoche 5. The Eight Categories by FPMT Masters Courses 6. -

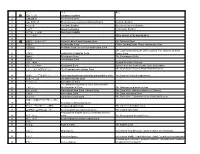

中文梵文英文1 佛釋迦牟尼佛sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛

中文 梵文 英文 1 佛 釋迦牟尼佛 Sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛 Vairocana Buddha 3 藥師璢璃光佛 Bhaiṣajya-guru-vaiḍūrya-prabhāṣa Buddha Medicine Buddha 4 阿彌陀佛 Amitābha Buddha Boundless radiance Buddha 5 不動佛 Akṣobhya Buddha Unshakable Buddha 6 然燈佛, 定光佛 Dipamkara Buddha 7 東方青龍佛 Azure Dragon of the East Buddha 8 9 經 金剛般若波羅密多經 Vajracchedika Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra The Diamond Sutra 10 華嚴經 Avataṃsaka Sutra Flower Garland Sutra; Flower Adornment Sutra 11 阿彌陀經 Amitābha Sutra; Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra The Lotus Sutra; Discourse of the Lotus of True Dharma; Dharma 12 法華經 Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sutra Flower Sutra; 13 楞嚴經 Śūraṅgama Sutra The Shurangama Sutra 14 楞伽經 Lankāvatāra Sūtra 15 四十二章經 Sutra in Forty-two Sections 16 地藏菩薩本願經 Kṣitigarbha Sutra Sutra of the Past Vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva 17 心經 ; 般若波羅蜜多心經 The Prajnaparamita Hrdaya Sutra The Heart Sutra, Heart of Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra 18 圓覺經;大方广圆觉修多罗了义经 Mahāvaipulya pūrṇabuddhasūtra prassanārtha sūtra The Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment 19 維摩詰所說經 Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa sūtra 20 三摩地王经 Samadhi-raja Sutra The Mahā prajñā pāramitā-sūtra; Śatasāhasrikā 21 大般若經 Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra; The Maha prajna paramita sutras 22 大般涅槃經 Mahā parinirvāṇa Sutra, Nirvana Sutra The Sutra of the ultimate extinction of Dharma 23 梵網經 Brahmajāla Sutra The Sutra of Brahma's Net 24 解深密經 Sandhinirmocana Sutra The Sutra of the Explanation of the Profound Secrets 勝鬘経;勝鬘師子吼一乘大方便方 25 廣經 Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra 26 佛说观无量寿佛经;十六觀經 Amitayur-dhyana Sutra The sixteen contemplate sutra 27 金光明經;金光明最勝王經 Suvarṇa-prabhāsa-uttamarāja Sutra The Golden-light Sutra -

Buddhist Meditation Systematic and Practical

Buddhist Meditation Systematic and Practical A Talk by The Buddhist Yogi C. M. Chen Written Down by Rev. B. KANTIPALO www.yogichen.org www.yogilin.org www.yogilin.net www.originalpurity.org Guru Chen Sitting in Meditation Table of Contents Foreword.......................................................................... i Foreword to the 1980 Edition………………………...... iii A Note to the Readers………………………………...... vi Foreword to the 1989 printing……………………......... viii Foreword to the 2011 Revised Edition………………..... ix Introduction…………………………………………...... 1 A Outward Biography B Inward Biography C Secret Biography D Most Secret Biography a The Attainment of Cause b The Attainment of Tao (The Path or Course) c The Attainment of Consequence: a Certainty of Enlightenment Chapter I……………………………………………....... 25 REASONS FOR WESTERN INTEREST IN THE PRACTICE OF MEDITATION A Remote cause – by reason of the Dharma-nature B By reason of Dharma-conditions 1 Foretold by sages 2 Effect of Bodhisattvas 3 All religions have the same basis 4 Correspondences between religions C By reason of the decline of Christianity 1 The scientific spirit 2 Post-Renaissance scepticism 3 Decline of Christian faith 4 Evolution D Immediate cause—by reason of stresses in western daily life Summary I Chapter II……………………………………………..... 47 WHAT IS THE REAL AND ULTIMATE PURPOSE OF PRACTICING BUDDHIST MEDITATIONS? A Mistakes in meditation 1 No foundation of renunciation 2 Use for evil 3 Lack of a guru 4 Only psychological—seven conditions for posture 5 Mixing traditions 6 Attraction of gaining powers 7 Thinking that Buddhism is utter atheism 8 Confusion about "no-soul" 9 Chan and the law of cause and effect 10 Ignorance of the highest purpose B The real purpose of meditation practice 1 A good foundation in Buddhist philosophy 2 Achieve the power of asamskrta 3 Realization of the Dharmakaya 4 Pleasure of the Sambhogakaya 5 Attainment of Nirmanakaya 6 Attainment of Svabhavikakaya 7 Attainment of Mahasukhakaya Chapter III…………………………………………..... -

The Large Sutra on Perfect Wisdom

THE LARGE SUTRA ON PERFECT WISDOM with the divisions of the Abhisamayālaṃkāra Translated by EDWARD CONZE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY, LOS ANGELES, LONDON Contents Contents 1 Abbreviations 5 Preface 7 Chapter Headings of THE PERFECTION OF WISDOM IN 18,000 LINES 11 V I 11 V II 12 V III 13 Divisions of the Abhisamayalankara 15 Introduction to Chapters 1-21 18 A 18 B 23 C 34 D 45 Outline of Chapters 1 – 21 53 TRANSLATION OF THE SUTRA 56 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 57 Chapter 2 THE THOUGHT OF ENLIGHTENMENT 66 Chapter 3 OBSERVATIONS 79 Chapter 4 EQUAL TO THE UNEQUALLED 112 Chapter 5 THE TONGUE 114 Chapter 6 SUBHUTI 116 Chapter 7 ENTRANCE INTO THE CERTAINTY OF SALVATION 124 Chapter 8 SRENIKA THE WANDERER 129 Chapter 9 THE SIGN 135 Chapter 10 LIKE ILLUSION 143 Chapter 11 SIMILES 149 Chapter 12 THE FORSAKING OF VIEWS 160 Chapter 13 THE SIX PERFECTIONS 163 Chapter 14 NEITHER BOUND NOR FREED 173 Chapter 15 THE CONCENTRATIONS 179 Chapter 16 ENTRANCE INTO THE DHARANI-DOORS 191 Chapter 17 THE PREPARTIONS FOR THE STAGES 203 Chapter 18 GOING FORTH ON THE STAGES 1 OF THE GREAT VEHICLE 221 Chapter 19 SURPASSING 225 Chapter 20 NONDUALITY 232 Chapter 21 SUBHUTI THE ELDER 238 Chapter 22 THE FIRST SAKRA CHAPTER 247 Chapter 23 HARD TO FATHOM 256 Chapter 24 INFINITE 259 Chapter 25 INFINITE 266 Chapter 26 GAINS 270 Chapter 27 THE SHRINE 276 Chapter 28 THE PROCLAMATION OF A BODHISATTVA’S QUALITIES 284 Chapter 29 THE HERETICS 288 Chapter 30 THE ADVANTAGES OF BEARING IN MIND AND OF REVERENCE 291 Chapter 31 ON RELICS 298 Chapter 32 THE DISTINCTION OF MERIT