Indigenous Governance in Winnipeg and Ottawa: Making Space for Self-Determination Julie Tomiak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

File No. CI 19-01-23329 the QUEEN's BENCH Winnipeg Centre

File No. CI 19-01-23329 THE QUEEN’S BENCH Winnipeg Centre IN THE MATTER OF: The Appointment of a Receiver pursuant to Section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act , R.S.C. 1985 c. B-3, as amended and Section 55 of The Court of Queen’s Bench Act , C.C.S.M. c. C280 BETWEEN: ROYAL BANK OF CANADA, Plaintiff, - and - 6382330 MANITOBA LTD., PGRP PROPERTIES INC., and 6472240 MANITOBA LTD. Defendants . SERVICE LIST AS AT May 15, 2020 FILLMORE RILEY LLP Barristers, Solicitors & Trademark Agents 1700 - 360 Main Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 Telephone: 204-957-8319 Facsimile: 204-954-0319 J. MICHAEL J. DOW File No. 180007-848/JMD FRDOCS_10130082.1 File No. CI 19-01-23329 THE QUEEN’S BENCH Winnipeg Centre IN THE MATTER OF: The Appointment of a Receiver pursuant to Section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act , R.S.C. 1985 c. B-3, as amended and Section 55 of The Court of Queen’s Bench Act , C.C.S.M. c. C280 BETWEEN: ROYAL BANK OF CANADA, Plaintiff, - and - 6382330 MANITOBA LTD., PGRP PROPERTIES INC., and 6472240 MANITOBA LTD. Defendants . SERVICE LIST Party/Counsel Telephone Email Party Representative FILLMORE RILEY LLP 204-957-8319 [email protected] Counsel for Royal 1700-360 Main Street Bank of Canada Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 J. MICHAEL J. DOW Facsimile: 204-954-0319 DELOITTE 204-944-3611 [email protected] Receiver RESTRUCTURING INC. 2300-360 Main Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 BRENT WARGA Facsimile: 204-947-2689 JOHN FRITZ 204-944-3586 [email protected] Facsimile 204-947-2689 THOMPSON DORFMAN 204-934-2378 [email protected] Counsel for the SWEATMAN LLP Receiver 1700-242 Hargrave Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V1 ROSS A. -

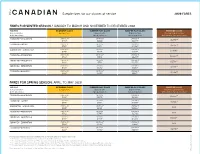

Sample Fares for Our Classes of Service 2020 FARES

Sample fares for our classes of service 2020 FARES FARES FOR WINTER SEASON / JANUARY TO MARCH AND NOVEMBER TO DECEMBER 2020 ROUTES ECONOMY CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS PRESTIGE CLASS Fares valid for Escape fare Upper berth, Cabin for two, Prestige cabin for two both directions fare per person fare per person with shower, fare per person — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO VANCOUVER $4,981††† $466* $1,111† $1,878†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO JASPER $3,753††† $385* $831† $1,406†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT EDMONTON VANCOUVER $2,020††† $190* $574† $969†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO EDMONTON $3,366††† $342* $751† $1,267†† STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG—VANCOUVER ††† † $3,366 $292* $754 $1,273†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG EDMONTON $2,201††† $158* $494† $835†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO WINNIPEG $2,783††† $229* $615† $1043†† FARES FOR SPRING SEASON: APRIL TO MAY 2020 ROUTES ECONOMY CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS PRESTIGE CLASS Fares valid for Escape fare Upper berth, Cabin for two, Prestige cabin for two both directions fare per person fare per person with shower, fare per person — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO VANCOUVER $5,336††† $466* $1,176† $1,988†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO JASPER $4,021††† $385* $881† $1,488†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT EDMONTON VANCOUVER N/A $190* $608† $1,026†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO EDMONTON N/A $342* $795† $1,342†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG VANCOUVER $3,607††† $292* $798† $1,349†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG EDMONTON N/A $158* $523† $884†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO WINNIPEG $2,981††† $229* $651† $1,104†† Prestige class between Vancouver and Edmonton is offered in summer on trains 3 and 4 only. -

Streaming-Live!* Ottawa Senators Vs Winnipeg Jets Live Free @4KHD 23 January 2021

*!streaming-live!* Ottawa Senators vs Winnipeg Jets Live Free @4KHD 23 January 2021 CLICK HERE TO WATCH LIVE FREE NHL 2021 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Starting XI Live Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 120 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Stream HD Notre Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 4231 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators PreMatch Build Up Ft James Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live WATCH ONLINE Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Online Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live NHL Ice Hockey League 2021, Live Streams Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live op tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Reddit Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 2021, Hockey 2021, Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 23rd January 2021, Broadcast Tohou USTV Live op tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Free On Tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live score Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Update Score Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live on radio 2021, Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Start Time Tohou Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Stream NHL Wedneshour,20th 247sports › board › Hockey-102607 › contents 1 hour ago — The Vancouver Canucks are 1-6-2 in their last nine games against the Montreal Arizona Coyotes the Vegas Golden Knights will try to snap out of their current threeLiVe'StrEAM)$* -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Winnipeg Chapter Brandon and Area Chapter

HSC Newsletter Manitoba Spring 2016 www.huntingtonsociety.ca RESOURCES & CHAPTER INFORMATION Manitoba News Winnipeg Chapter Winnipeg Chapter President: Vern Barrett Tel: (204) 694-1779 Chapter News Thank you to the volunteers who helped out at the Guns ‘n’ Hoses hockey Brandon Chapter game on February 13! What another great chance to build awareness and President: Sandra Harrison raise funds for HSC! Tel: (204) 726-8323 Upcoming Events HSC National Office Run2Finish HD: Saturday, June 4, 2016, Assiniboine Park Conservatory 151 Frederick Street, Suite 400 Kitchener, ON N2H 2M2 5K Walk (shortcuts permitted), 5K or 10K Run. Family event – strollers, roller 1-800-998 -7398 blades, leashed pets welcome! Email [email protected] or check [email protected] www.hdmanitoba.ca for details! __________________________________ Manitoba Huntington Disease Resource Huntington Indy Go-Kart Challenge: Sunday, September 11, 2016, Thunder Centre Rapids Fun Park, Headingley (just past Assiniboia Downs) Family fun, enter teams of up to 6 people. Contact Vern Barret 204-694-1779 Marla Benjamin, Director or [email protected]. www.hdmanitoba.ca for more info! 200 Woodlawn St Winnipeg, MB R3J 2H7 Support Group Tel: (204) 772-4617 th [email protected] 4 Tuesday of the month, 7pm – 8:30pm, Winnipeg. For more details, (204)-772-4617 or [email protected] _______________________________ ___ The Manitoba Huntington Disease Resource Centre (MB-HDRC) located in Winnipeg, offers the Huntington Society of Brandon and Area Chapter Canada’s Family Services Program. Marla Benjamin, is available 3 days per week to offer services to individuals, families, and Upcoming Events professionals who are living with Going the Distance 4 HD: August 24-28. -

Niagara Regional Native Centre

Niagara Regional Native Centre HANYOH Community Snaphot Employment & Education Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Labour Market Profile ........................................................................................................ 3 2. Research Report Methodology ................................................................................................ 8 2.1 Research Report Scope ...................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Research Report Issues and Questions .............................................................................. 8 2.3 Research Report Methodology .......................................................................................... 9 2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance ............................................................... 10 3. Research Report Findings ...................................................................................................... 12 3.1 Employment Status Findings ........................................................................................... 12 3.2 Levels of Education -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov. -

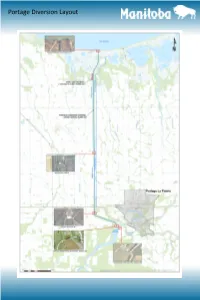

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects Assiniboine River Control Structure Public and worker safety improvements Completed in 2015 Works include fencing, signage, and safety boom Electrical and mechanical upgrades Ongoing Works include upgrades to 600V electrical distribution system, replacement of gate control system and mo- tor control center, new bulkhead gate hoist, new stand-by diesel generator fuel/piping system and new ex- terior diesel generator Portage Diversion East Outside Drain Reconstruction of 18 km of drain Completed in 2013 Replacement of culverts beneath three (3) railway crossings Completed in 2018 Recent and Future Projects Portage Diversion Outlet Structure Construction of temporary rock apron to stabilize outlet structure Completed in 2018 Conceptual Design for options to repair or replace structure Completed in 2018 Outlet structure major repair or replacement prioritized over next few years Portage Diversion Channel Removal of sedimentation within channel Completed in 2017 Groundwater/soil salinity study for the Portage Diversion Ongoing—commenced in 2016 Enhancement of East Dike north of PR 227 to address freeboard is- sues at design capacity of 25,000 cfs Proposed to commence in 2018 Multi-phase over the next couple of years Failsafe assessment and potential enhancement of West Dike to han- dle design capacity of 25,000 cfs Prioritized for future years—yet to be approved Historical Operating Guidelines Portage Diversion Operating Guidelines 1984 Red River Floodway Program of Operation Operation Objectives The Portage Diversion will be operated to meet these objectives: 1. To provide maximum benefits to the City of Winnipeg and areas along the Assiniboine River downstream of Portage la Prairie. -

Your Success Is Rooted in Our Soil. Our

YOUR SUCCESS IS ROOTED IN OUR SOIL. INVESTMENT PROFILE INVESTMENT PROFILE OUR VALUE TABLE OF PROPOSITION CONTENTS Home to a growing cluster of agri-food manufacturing operations 4 STRATEGIC LOCATION KEY COMMUNITY CONTACTS ranging from 30 to 350 employees, Portage la Prairie is immersed 6 LABOUR DEMOGRAPHICS EVE O LEA RY in agricultural production with optimal access to both resources, as 7 Workforce Development Exec ut ive Director well as major transportation routes to get your product to market. Porta g e Regional Economic Development This, combined with Manitoba’s competitive hydro electric utility 8 THRIVING AG SECTOR E -mail: e [email protected] rates and abundant capacity of water for the food manufacturing Oce: 204-856-5000 10 VALUE-ADDED PROCESSING M obile: 2 0 4 -870-9050 sector, create an ideal location for your next development. 11 RECENT INVESTMENT NET TIE NEU DORF Chief Ad ministrative Ocer 12 MANITOBA ADVANTAGE Rural Municipality of Portag e la Prairie 14 Construction Costs / Tax Rates E-mail: n neudorf@rmofpo rtage.ca Phone: 204-857-3821 16 WE’RE READY FOR YOU 16 Inventory of Available Land/Buildings NATHA N PETO City M a nager 18 SOUTHPORT AEROSPACE City o f P ortage l a P rairie CENTRE INC. E-mail: n [email protected] Phone: 2 04-239-8336 KINELM BROOKES General Manager Portage La Prairie Planning District E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 204-239-8345 YOUR SUCCESS IS ROOTED IN OUR SOIL 3 INVESTMENT PROFILE STRATEGIC LOCATION Trans-Canada Highway PROXIMITY TO WINNIPEG CN Railway WE ARE THE GEOGRAPHIC Manitoba’s capital city, with a population of more than 709,000, sits within the radius of CENTRE OF NORTH AMERICA CP Railway Portage la Prairie’s trade area. -

Portage La Prairie Mall 2450 SASKATCHEWAN AVENUE WEST > PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE, MB

FOR LEASE > RETAIL OPPORTUNITY Portage la Prairie Mall 2450 SASKATCHEWAN AVENUE WEST > PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE, MB Property Description Contact Us: Portage La Prairie Mall caters to the town of Portage la Prairie & the outlying Colliers International, trade area and is anchored by a Rona Dealer network store occupying 62,000 John Prall sq. ft. +1 204 926 3839 Portage la Prairie Mall is the Region’s primary Shopping Centre providing good [email protected] exposure to Saskatchewan Avenue with excellent access and egress from two traffic controlled intersections at each end of the parking lot. Kris Mutcher Location +1 204 926 3838 Located at the corner of Highway # 1A and 24th Street in Portage La Prairie [email protected] Rent Additional Rent Size of Centre TBD $4.83/ sq. ft. (2018 est.) 187,000 sq. ft. Opportunities • 2 pad sites available • Various units as shown on mall site plan • Previous Safeway premises of 38,000 sq. ft. • 5,900 SF Restaurant Opportunity 5th Floor - 305 Broadway Winnipeg, MB R3C 3J7 Main +1 204 943 1600 Fax +1 204 943 4793 www.colliers.com Adjacent Retailers Other retailers in the immediate area include: Walmart Canadian Tire Co-op Grocery Store Sobeys Boston Pizza Tim Hortons McDonald’s Reitmans Dufrense Furniture Access The four lane divided Trans Canada Highway runs adjacent to Portage la Prairie. As the major East-West route in Canada, the highway provides easy access to Winnipeg 75 kilometers to the east, and other major centres beyond. The Trans Canada Highway also provides access to many north-south routes with easy access to the United States and many other points, which means unlimited access by all of the major international carriers for long distance trucking needs. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

OUR STRENGTH IS OURSELVES": IDENTITY, STATUS, AND CULTURAL REVITALIZATION AMONG THE MI'KMAQ IN NEWFOUNDLAND by © Janice Esther Tulk A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Music Memorial University of Newfoundland July 2008 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47919-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47919-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Supporting Healthy Child Development in Aboriginal Families

A Sense of Belonging: Supporting Healthy Child Development in Aboriginal Families Best Start: Ontario’s Maternal, Newborn and Early Child Development Resource Centre A Sense of Belonging: Supporting Healthy Child Development in Aboriginal Families Best Start: Ontario’s Maternal, Newborn and Early Child Development Resource Centre This document has been prepared with funds provided by the Government of Ontario. The information herein reflects the views of the author and is not officially endorsed by the Government of Ontario. The resources and programs cited throughout this guide are not necessarily endorsed by the Best Start Resource Centre or the Government of Ontario. Use of this Resource The Best Start Resource Centre thanks you for your interest in, and support of, our work. Best Start permits others to copy, distribute or reference the work for non-commercial purposes on condition that full credit is given. Because our resources are designed to support local health promotion nitiatives, we would appreciate knowing how this resource has supported, or been integrated into, your work ([email protected]). Citation Best Start Resource Centre (2011). A Sense of Belonging: Supporting Healthy Child Development in Aboriginal Families . Toronto, Ontario, Canada: author. A Sense of Belonging: Supporting Healthy Child Development in Aboriginal Families 1 Acknowledgements This resource was created through the involvement of many generous people. Sincere appreciation is extended to the Aboriginal working group who guided the process and to the key informants who contributed in defining the content. Many thanks also to the Aboriginal parents who freely shared their knowledge and experiences. Their wisdom was incredibly valuable in developing this resource.