The Unique Case of Winnipeg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

File No. CI 19-01-23329 the QUEEN's BENCH Winnipeg Centre

File No. CI 19-01-23329 THE QUEEN’S BENCH Winnipeg Centre IN THE MATTER OF: The Appointment of a Receiver pursuant to Section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act , R.S.C. 1985 c. B-3, as amended and Section 55 of The Court of Queen’s Bench Act , C.C.S.M. c. C280 BETWEEN: ROYAL BANK OF CANADA, Plaintiff, - and - 6382330 MANITOBA LTD., PGRP PROPERTIES INC., and 6472240 MANITOBA LTD. Defendants . SERVICE LIST AS AT May 15, 2020 FILLMORE RILEY LLP Barristers, Solicitors & Trademark Agents 1700 - 360 Main Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 Telephone: 204-957-8319 Facsimile: 204-954-0319 J. MICHAEL J. DOW File No. 180007-848/JMD FRDOCS_10130082.1 File No. CI 19-01-23329 THE QUEEN’S BENCH Winnipeg Centre IN THE MATTER OF: The Appointment of a Receiver pursuant to Section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act , R.S.C. 1985 c. B-3, as amended and Section 55 of The Court of Queen’s Bench Act , C.C.S.M. c. C280 BETWEEN: ROYAL BANK OF CANADA, Plaintiff, - and - 6382330 MANITOBA LTD., PGRP PROPERTIES INC., and 6472240 MANITOBA LTD. Defendants . SERVICE LIST Party/Counsel Telephone Email Party Representative FILLMORE RILEY LLP 204-957-8319 [email protected] Counsel for Royal 1700-360 Main Street Bank of Canada Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 J. MICHAEL J. DOW Facsimile: 204-954-0319 DELOITTE 204-944-3611 [email protected] Receiver RESTRUCTURING INC. 2300-360 Main Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 3Z3 BRENT WARGA Facsimile: 204-947-2689 JOHN FRITZ 204-944-3586 [email protected] Facsimile 204-947-2689 THOMPSON DORFMAN 204-934-2378 [email protected] Counsel for the SWEATMAN LLP Receiver 1700-242 Hargrave Street Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V1 ROSS A. -

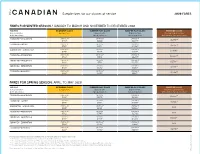

Sample Fares for Our Classes of Service 2020 FARES

Sample fares for our classes of service 2020 FARES FARES FOR WINTER SEASON / JANUARY TO MARCH AND NOVEMBER TO DECEMBER 2020 ROUTES ECONOMY CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS PRESTIGE CLASS Fares valid for Escape fare Upper berth, Cabin for two, Prestige cabin for two both directions fare per person fare per person with shower, fare per person — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO VANCOUVER $4,981††† $466* $1,111† $1,878†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO JASPER $3,753††† $385* $831† $1,406†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT EDMONTON VANCOUVER $2,020††† $190* $574† $969†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO EDMONTON $3,366††† $342* $751† $1,267†† STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG—VANCOUVER ††† † $3,366 $292* $754 $1,273†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG EDMONTON $2,201††† $158* $494† $835†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO WINNIPEG $2,783††† $229* $615† $1043†† FARES FOR SPRING SEASON: APRIL TO MAY 2020 ROUTES ECONOMY CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS SLEEPER PLUS CLASS PRESTIGE CLASS Fares valid for Escape fare Upper berth, Cabin for two, Prestige cabin for two both directions fare per person fare per person with shower, fare per person — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO VANCOUVER $5,336††† $466* $1,176† $1,988†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO JASPER $4,021††† $385* $881† $1,488†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT EDMONTON VANCOUVER N/A $190* $608† $1,026†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO EDMONTON N/A $342* $795† $1,342†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG VANCOUVER $3,607††† $292* $798† $1,349†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT WINNIPEG EDMONTON N/A $158* $523† $884†† — STARTING AT STARTING AT STARTING AT TORONTO WINNIPEG $2,981††† $229* $651† $1,104†† Prestige class between Vancouver and Edmonton is offered in summer on trains 3 and 4 only. -

Conflicts-In-Federal-Systems-Mintz

PUBLICATIONS SPP Research Paper Volume 12:14 April 2019 TWO DIFFERENT CONFLICTS IN FEDERAL SYSTEMS: AN APPLICATION TO CANADA*† Jack M. Mintz SUMMARY Canadians are used to taking seriously the threat of separation when it comes to Quebec, but a more serious, less manageable form of conflict may eventually emerge in the federation between Western Canada and the rest of Canada. Where the Canadian government has been successful so far in managing the “conflict of taste” that has led to Quebec’s historic discomfort in the Canadian federation, because the federal government possesses the tools to address that challenge, it does not have the same tools to manage the “conflict of claim” that is creating increased dissatisfaction with Confederation in the West. The result is that Canada is a less stable federation than many observers realize. Interestingly, the future of its unity depends largely on whether the West is able to establish a lasting political alliance with Ontario even though that would mean Quebec no longer being critical for national coalitions. Conflicts of taste revolve around differences in political preferences between regions within a federation. While Quebec is animated by its different culture, history and language than the rest of Canada, which has created a conflict of taste, mechanisms have been put in place to help mitigate the friction, including: Provincial powers over key cultural institutions such as education and health, special fiscal and immigration arrangements for Quebec, guaranteed bilingualism in federal institutions and tax-collection powers unique to Quebec. Quebec’s ability to wield federal power through a Central Canadian alliance with Ontario has also helped partially alleviate the province’s discomfort within Confederation. -

Town Charter

Taken from: Province of New Hampshire—Records of Council 1716 ( pages 690 & 691 ) Province of New Hampshire At a Council held at the Council chambers in Portsmouth March 14, 17151715----16161616 PRESENT: The Honorable George Vaughan, Esq., Lt. Governor; Richard Waldron, Samuel Penhallow, John Plaisted, Mark Hunking, John Wentworth, Esquires. Mr. Smith appeared at this Board on behalf of sundry inhabitants of Swampscott and presented a petition (against making Swampscott a town) as on file, bearing date, January 14, 1715-6*. Notwithstanding which petition and sundry other objections which have been made since ye first motions about making said Swampscott a town, it is In Council Ordered, that Swampscott Patent land be a township by the name of Stratham, and have full power to choose officers as other towns within this Province, and that the bounds of said town be according to the limits specified in a petition proffered to this board by Mr. Andrew Wiggin, the 13 th day of January last, except some families lying near to Greenland (viz.) John Hill, Thomas Leatherby, Enoch Barker, and Michael Hicks, which said some families shall belong to the Parish of Greenland: And that a meeting house be built on the King’s great road leading from Greenland to Exeter, within half a mile of the midway between ye bounds yet are next Exeter and the bounds that are next Greenland, as the road goes; and that they be obliged to have a learned orthodox minister to preach in said meeting house within one year from the date hereof. R. Waldron, Cleric Con. -

Streaming-Live!* Ottawa Senators Vs Winnipeg Jets Live Free @4KHD 23 January 2021

*!streaming-live!* Ottawa Senators vs Winnipeg Jets Live Free @4KHD 23 January 2021 CLICK HERE TO WATCH LIVE FREE NHL 2021 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Starting XI Live Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 120 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Stream HD Notre Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 4231 Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators PreMatch Build Up Ft James Video result for Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live WATCH ONLINE Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Online Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live NHL Ice Hockey League 2021, Live Streams Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live op tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Reddit Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 2021, Hockey 2021, Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live 23rd January 2021, Broadcast Tohou USTV Live op tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Free On Tv Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live score Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Update Score Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live on radio 2021, Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Start Time Tohou Winnipeg Jets vs Ottawa Senators Live Stream NHL Wedneshour,20th 247sports › board › Hockey-102607 › contents 1 hour ago — The Vancouver Canucks are 1-6-2 in their last nine games against the Montreal Arizona Coyotes the Vegas Golden Knights will try to snap out of their current threeLiVe'StrEAM)$* -

A Global Comparison of Non-Sovereign Island Territories: the Search for ‘True Equality’

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 43-66 A global comparison of non-sovereign island territories: the search for ‘true equality’ Malcom Ferdinand CNRS, Paris, France [email protected] Gert Oostindie KITLV, the Netherlands Leiden University, the Netherlands [email protected] (corresponding author) Wouter Veenendaal KITLV, the Netherlands Leiden University, the Netherlands [email protected] Abstract: For a great majority of former colonies, the outcome of decolonization was independence. Yet scattered across the globe, remnants of former colonial empires are still non-sovereign as part of larger metropolitan states. There is little drive for independence in these territories, virtually all of which are small island nations, also known as sub-national island jurisdictions (SNIJs). Why do so many former colonial territories choose to remain non-sovereign? In this paper we attempt to answer this question by conducting a global comparative study of non-sovereign jurisdictions. We start off by analyzing their present economic, social and political conditions, after which we assess local levels of (dis)content with the contemporary political status, and their articulation in postcolonial politics. We find that levels of discontent and frustration covary with the particular demographic, socio- economic and historical-cultural conditions of individual territories. While significant independence movements can be observed in only two or three jurisdictions, in virtually all cases there is profound dissatisfaction and frustration with the contemporary non-sovereign arrangement and its outcomes. Instead of achieving independence, the territories’ real struggle nowadays is for obtaining ‘true equality’ with the metropolis, as well as recognition of their distinct cultural identities. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Winnipeg Chapter Brandon and Area Chapter

HSC Newsletter Manitoba Spring 2016 www.huntingtonsociety.ca RESOURCES & CHAPTER INFORMATION Manitoba News Winnipeg Chapter Winnipeg Chapter President: Vern Barrett Tel: (204) 694-1779 Chapter News Thank you to the volunteers who helped out at the Guns ‘n’ Hoses hockey Brandon Chapter game on February 13! What another great chance to build awareness and President: Sandra Harrison raise funds for HSC! Tel: (204) 726-8323 Upcoming Events HSC National Office Run2Finish HD: Saturday, June 4, 2016, Assiniboine Park Conservatory 151 Frederick Street, Suite 400 Kitchener, ON N2H 2M2 5K Walk (shortcuts permitted), 5K or 10K Run. Family event – strollers, roller 1-800-998 -7398 blades, leashed pets welcome! Email [email protected] or check [email protected] www.hdmanitoba.ca for details! __________________________________ Manitoba Huntington Disease Resource Huntington Indy Go-Kart Challenge: Sunday, September 11, 2016, Thunder Centre Rapids Fun Park, Headingley (just past Assiniboia Downs) Family fun, enter teams of up to 6 people. Contact Vern Barret 204-694-1779 Marla Benjamin, Director or [email protected]. www.hdmanitoba.ca for more info! 200 Woodlawn St Winnipeg, MB R3J 2H7 Support Group Tel: (204) 772-4617 th [email protected] 4 Tuesday of the month, 7pm – 8:30pm, Winnipeg. For more details, (204)-772-4617 or [email protected] _______________________________ ___ The Manitoba Huntington Disease Resource Centre (MB-HDRC) located in Winnipeg, offers the Huntington Society of Brandon and Area Chapter Canada’s Family Services Program. Marla Benjamin, is available 3 days per week to offer services to individuals, families, and Upcoming Events professionals who are living with Going the Distance 4 HD: August 24-28. -

Urban Planning Approaches in Divided Cities

ITU A|Z • Vol 13 No 1 • March 2016 • 139-156 Urban planning approaches in divided cities Gizem CANER1, Fulin BÖLEN2 1 [email protected] • Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Graduate School of Science, Engineering and Technology, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey 2 [email protected] • Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Architecture, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey Received: April 2014 • Final Acceptance: December 2015 Abstract This paper provides a comparative analysis of planning approaches in divided cities in order to investigate the role of planning in alleviating or exacerbating urban division in these societies. It analyses four urban areas—Berlin, Beirut, Belfast, Jerusalem—either of which has experienced or still experiences extreme divisions related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, and/or culture. Each case study is investigated in terms of planning approaches before division and after reunifi- cation (if applicable). The relation between division and planning is reciprocal: planning effects, and is effected by urban division. Therefore, it is generally assumed that traditional planning approaches are insufficient and that the recognized engagement meth- ods of planners in the planning process are ineffective to overcome the problems posed by divided cities. Theoretically, a variety of urban scholars have proposed different perspectives on this challenge. In analysing the role of planning in di- vided cities, both the role of planners, and planning interventions are evaluated within the light of related literature. The case studies indicate that even though different planning approaches have different consequences on the ground, there is a universal trend in harmony with the rest of the world in reshaping these cities. -

The Functions of a Capital City: Williamsburg and Its "Public Times," 1699-1765

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1980 The functions of a capital city: Williamsburg and its "Public Times," 1699-1765 Mary S. Hoffschwelle College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hoffschwelle, Mary S., "The functions of a capital city: Williamsburg and its "Public Times," 1699-1765" (1980). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625107. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ja0j-0893 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FUNCTIONS OF A CAPITAL CITY: »» WILLIAMSBURG AND ITS "PUBLICK T I M E S 1699-1765 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary S„ Hoffschwelle 1980 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Mary S. Hoffschwelle Approved, August 1980 i / S A /] KdJL, C.£PC„ Kevin Kelly Q TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ........................... ................... iv CHAPTER I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ........................... 2 CHAPTER II. THE URBAN IMPULSE IN COLONIAL VIRGINIA AND ITS IMPLEMENTATION ........................... 14 CHAPTER III. THE CAPITAL ACQUIRES A LIFE OF ITS OWN: PUBLIC TIMES ................... -

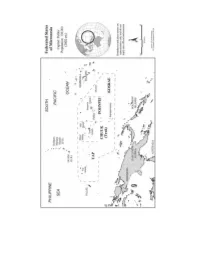

FC-Micronesia.Pdf

The Federated States of Micronesia DIRK ANTHONY BALLENDORF 1 history and development of federalism Micronesia is a collection of island groups in the Pacific Ocean comprised of four major clusters: the Marianas, Carolines, Marshalls, and Gilberts (now known as Kiribati). The Federated States of Micronesia (fsm) is part of the Caroline island archipelago. The fsm consists of the island groups of Chuuk (formerly Truk), Yap, Pohnpei (formerly Ponape) and Kosrae – it is thus a subset of Micronesia writ large. The total land area of the fsm is approximately 700 km, but the islands are spread over 2.5 million km. It has a population of approximately 108,000 people. The history of Micronesia is one of almost continuous exploitation since Ferdinand Magellan first landed briefly in Guam in 1521. Four successive colonial administrations – Spanish, 1521 to 1898; German, 1899 to 1914; Japanese, 1914 to 1944; and American, 1944 to indepen- dence in 1986 – have controlled the many small islands of Micronesia. In 1947, the United States was assigned administration of Microne- sia under a United Nations Trusteeship Agreement. Like previous co- lonial administrations, the American administration was centralized, with Saipan in the northern Marianas as the capital. The Micronesian peoples were divided into six separate administrative districts: Mari- anas, Yap, Palau, Truk (now Chuuk), Ponape (now Pohnpei), and the Marshalls, and they remained largely self-sufficient and isolated from the rest of the world. In 1977, a seventh district, Kosrae, was created from a division of the Ponape district. 217 Federated States of Micronesia Minimal attention was paid by both the United States and the United Nations to US obligations under the un Charter until a un mission to the area during the Kennedy administration drew attention to an extensive list of local complaints. -

Geographical Characteristics of the State

Geographical Characteristics of the State The Cultural Mosaic Fellman, and Notes from D.J. Zeigler of Old Dominion Vocab Review • State • Sovereignty • Nation • Nation-state • Binational or Multinational • Stateless Nation • Nationalism Territoriality • The modern state is an example of a common human tendency: the need to belong to a larger group that controls its own piece of the earth, its own territory. • This is called territoriality: a cultural strategy that uses power to control area and communicate that control, subjugating inhabitants and acquiring resources. Shapes of States • Compact States – Efficient – Theoretically round – Capital in center – Shortest possible boundaries to defend – Improved communications – Ex. Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Poland, Uraguay Shapes of States • Prorupted States – w./large projecting extension – Sometimes natural – Sometimes to gain a resource or advantage, such as to reach water, create a buffer zone – Ex. Thailand, Myanmar, Namibia, Mozambique, Cameroon, Congo Shapes of States • Elongated States – States that are long and narrow – Suffer from poor internal communication – Capital may be isolated – Ex. Chile, Norway, Vietnam, Italy, Gambia Shapes of States • Fragmented States – Several discontinuous pieces of territory – Technically, all states w/off shore islands – Two kinds: separated by water & separated by an intervening state – Exclave – – Ex. Indonesia, USA, Russia, Philippines Shapes of States • Perforated States – A country that completely surrounds another state – Enclave – the surrounded territory – Ex. Lesotho/South Africa, San Marino & Vatican City/Italy Enclaves and exclaves • An enclave is an area surrounded by a country but not ruled by it. – It can be self-governing or an exclave of another country. Example-- Lesotho – Can be problematic for the surrounding country.