Urban Planning Approaches in Divided Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Division and the City: Spatial Dramas of Divided Cities

ARTICLE MEGARON 2015;10(4):565-579 DOI: 10.5505/MEGARON.2015.29290 Division and the City: Spatial Dramas of Divided Cities Bölünme ve Kent: Bölünmüş Kentlerin Mekânsal Trajedileri Gizem CANER ABSTRACT ÖZ Every contemporary city is divided to a certain extent. The Günümüz şehirlerinin neredeyse tamamı kavramsal bağlam- present study is concerned with urban division defined by da bir düzeye kadar bölünmüştür. Ancak bu yazı, milliyet, extreme tensions related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, etnisite, din ve kültürle ilişkili uç gerilimlerin neden olduğu, and culture, which are channelled into urban arenas. Once daha spesifik bir kentsel bölünme türüyle ilgilenmektedir. Bu these contestations are made spatially visible, the “divided çatışmalar kentsel alanlarda ses bulmaktadır ve mekânsal city” with which this study is concerned appears. Well-known görünürlük kazandıkları zaman, bu yazının da konusu olan examples of such “divided” cities are Belfast, Jerusalem, Nic- ‘bölünmüş kentler’ ortaya çıkmaktadır. Bu şehirler arasında osia, Mostar, Beirut, and Berlin. Due to distinctive attributes, en iyi bilinen örnekler Belfast, Kudüs, Lefkoşa, Mostar, Bey- these cities contain an exclusive discourse that differentiates rut ve Berlin’dir. Özgün niteliklerinden dolayı, bu şehirler, them from other urban areas. In this context, the aim of the kendilerini diğer kentsel alanlardan ayıran özel bir söyleme present study was to comparatively analyze urban conse- sahiptirler. Bu çerçevede, bu yazının ana konusu, seçilmiş quences of division in selected case studies: Belfast and Ber- şehir örneklerinde–Belfast ve Berlin–bölünmenin kentsel so- lin. As each city has unique attributes of geography, history, nuçlarının karşılaştırmalı olarak analiz edilmesidir. Her kent, and economic development, the processes and outcomes of kendine has coğrafi, tarihi ve ekonomik gelişme özelliklerine their division differ substantially. -

EAA Meeting 2016 Vilnius

www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME Organisers CONTENTS President Words .................................................................................... 5 Welcome Message ................................................................................ 9 Symbol of the Annual Meeting .............................................................. 13 Commitees of EAA Vilnius 2016 ............................................................ 14 Sponsors and Partners European Association of Archaeologists................................................ 15 GENERAL PROGRAMME Opening Ceremony and Welcome Reception ................................. 27 General Programme for the EAA Vilnius 2016 Meeting.................... 30 Annual Membership Business Meeting Agenda ............................. 33 Opening Ceremony of the Archaelogical Exhibition ....................... 35 Special Offers ............................................................................... 36 Excursions Programme ................................................................. 43 Visiting Vilnius ............................................................................... 57 Venue Maps .................................................................................. 64 Exhibition ...................................................................................... 80 Exhibitors ...................................................................................... 82 Poster Presentations and Programme ........................................... -

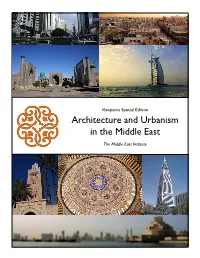

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

State Fragility in Lebanon: Proximate Causes and Sources of Resilience

APRIL 2018 State fragility in Lebanon: Proximate causes and sources of resilience Bilal Malaeb This report is part of an initiative by the International Growth Centre’s Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development. While every effort has been made to ensure this is an evidence-based report, limited data availability necessitated the use of media reports and other sources. The opinions in this report do not necessarily represent those of the IGC, the Commission, or the institutions to which I belong. Any errors remain my own. Bilal Malaeb University of Oxford and University of Southampton [email protected] About the commission The LSE-Oxford Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development was launched in March 2017 to guide policy to address state fragility. The commission, established under the auspices of the International Growth Centre, is sponsored by LSE and University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government. It is funded from the LSE KEI Fund and the British Academy’s Sustainable Development Programme through the Global Challenges Research Fund. Cover photo: Fogline Studio/Getty 2 State fragility in Lebanon: Proximate causes and sources of resilience Contents Introduction 4 State (il)legitimacy 9 Ineffective state with limited capacity 15 The private sector: A source of resilience 22 Security 26 Resilience 29 Conclusion and policy recommendations 30 References 36 3 State fragility in Lebanon: Proximate causes and sources of resilience Introduction Lebanon is an Arab-Mediterranean country that has endured a turbulent past and continues to suffer its consequences. The country enjoys a strong private sector and resilient communities. -

Baku Airport Bristol Hotel, Vienna Corinthia Hotel Budapest Corinthia

Europe Baku Airport Baku Azerbaijan Bristol Hotel, Vienna Vienna Austria Corinthia Hotel Budapest Budapest Hungary Corinthia Nevskij Palace Hotel, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Fairmont Hotel Flame Towers Baku Azerbaijan Four Seasons Hotel Gresham Palace Budapest Hungary Grand Hotel Europe, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Grand Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton DoubleTree Zagreb Zagreb Croatia Hilton Hotel am Stadtpark, Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton Hotel Dusseldorf Dusseldorf Germany Hilton Milan Milan Italy Hotel Danieli Venice Venice Italy Hotel Palazzo Parigi Milan Italy Hotel Vier Jahreszieten Hamburg Hamburg Germany Hyatt Regency Belgrade Belgrade Serbia Hyatt Regenct Cologne Cologne Germany Hyatt Regency Mainz Mainz Germany Intercontinental Hotel Davos Davos Switzerland Kempinski Geneva Geneva Switzerland Marriott Aurora, Moscow Moscow Russia Marriott Courtyard, Pratteln Pratteln Switzerland Park Hyatt, Zurich Zurich Switzerland Radisson Royal Hotel Ukraine, Moscow Moscow Russia Sacher Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Suvretta House Hotel, St Moritz St Moritz Switzerland Vals Kurhotel Vals Switzerland Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam Amsterdam Netherlands France Ascott Arc de Triomphe Paris France Balmoral Paris Paris France Casino de Monte Carlo Monte Carlo Monaco Dolce Fregate Saint-Cyr-sur-mer Saint-Cyr-sur-mer France Duc de Saint-Simon Paris France Four Seasons George V Paris France Fouquets Paris Hotel & Restaurants Paris France Hôtel de Paris Monaco Monaco Hôtel du Palais Biarritz France Hôtel Hermitage Monaco Monaco Monaco Hôtel -

Hillgroveis Thebestfor Weddings PLAINSAILINGFORPIERCE

2 I SUNDAY TRADER www.sundaylife.co.uk Sunday Life 7 June 2015 PLAIN SAILING FOR PIERCE Bringingyouall PIERCE McConnell, aged 8, from Newtownabbey, helps P&O Ferries kick off the summer season in style with thelatestdeals a ‘Kids Go Free’ offer that will please the whole family. From today and throughout this year, children aged 15 Travel andoffers years and younger can travel free on sailings between Larne to Cairnryan and Troon. Visit www.POferries.com. ByTom Sweeney OST people who follow the Camino de Santiago walk it, while many others cycle. A few do it on horseback and fewer still set out in wheelchairs with the help Mof friends. Whatever their means of getting to Santiago de Compostela, everyone has the same goal — to visit the tomb of St James. Santiago is the capital of Galicia, the bit of Spain that sits on top of Portugal like an umbrella and gets more rain than North- ern Ireland in the spring. However, when the sun shines it’s hot to trot — or pedal or GIANT INCENSE BURNER: The botafumeiro in the cathedral, the Abastos market in Santiago and the cheeky bishop’s backside gargoyle on the cathedral roof walk. The 13th century cathedral in which the saint’s remains It’s high time you made a pilgrimage to Spain’s sensational Santiago reside in a silver sarcophagus in the crypt attracts pilgrims There’s also an Irish Way Dublin to Santiago that take their blisters before visiting but it did put a smirk on their sardines plus a huge selection of of all religions and none. -

The Functions of a Capital City: Williamsburg and Its "Public Times," 1699-1765

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1980 The functions of a capital city: Williamsburg and its "Public Times," 1699-1765 Mary S. Hoffschwelle College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hoffschwelle, Mary S., "The functions of a capital city: Williamsburg and its "Public Times," 1699-1765" (1980). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625107. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ja0j-0893 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FUNCTIONS OF A CAPITAL CITY: »» WILLIAMSBURG AND ITS "PUBLICK T I M E S 1699-1765 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary S„ Hoffschwelle 1980 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Mary S. Hoffschwelle Approved, August 1980 i / S A /] KdJL, C.£PC„ Kevin Kelly Q TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ........................... ................... iv CHAPTER I. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ........................... 2 CHAPTER II. THE URBAN IMPULSE IN COLONIAL VIRGINIA AND ITS IMPLEMENTATION ........................... 14 CHAPTER III. THE CAPITAL ACQUIRES A LIFE OF ITS OWN: PUBLIC TIMES ................... -

UN Task Force Student Mobility Meeting 14-15 March 2018, Vilnius

3.i - SM_Minutes_Vilnius_2018_03 UN Task force Student mobility meeting 14-15 March 2018, Vilnius Agenda & minute Follow-up on recurring/earlier topics 1. Confirm MoM Bologna, November 2018 Confirmed 2. UN Research grant Call 2018 selection (applications from 15 universities) Change text website and application form (3 > 2 months)* ii-agreement not necessary for traineeships Mail to Thessaloniki/Istanbul/Bratislava on Erasmus+ eligibility (> 3months period) Helsinki to Belfast is 2,5 months and in the application we only ask for explanation if period is longer than 3 months* SC/Joint meeting still needs to decide on the 11th grant (left over from last year) maybe 15 grants, since UN did underspend in 17-18 (update Gérald)-> 15 grants approved by SC at Joint meeting. Check (9) un(der)-represented member institutions and if necessary adjust promotional approach 5 members still have not submitted/nominated, Rita will send mail asking why and offer promotional assistance/visit: Belfast/Bergen/Bologna/Lund/Malta. revise YRG report questions to get useful quotes Wait until after the questions to the 5 have been sent, only if they specifically ask for promotional material. 3. Statistics 2016-2017 almost complete; data Budapest still missing - Marleen overview will be sent to SC before Joint meeting 4. Promotion ‘tour’; on hold until AGM Bratislava > also communicate the promotional visit option through Newsletter/googlegroup- comment from joint SC & TF meeting 5. UN website TF pages - update TF members & picture (?) Overview of collected -

The Quest of Beirut´S Public Spaces, Analysis of Beirut Central District

International Journal of Scientific Engineering and Applied Science (IJSEAS) – Volume-7, Issue-8, August 2021 ISSN: 2395-3470 www.ijseas.com The quest of Beirut´s public spaces, analysis of Beirut Central District Mariam Eissa Ph.D. Candidate, School of Architecture, University of Minho Abstract: This paper presents an analysis of the renovation of the public space in Beirut done by Solidere -The company in charge of planning and redeveloping Beirut Central District- after the civil war. The aims of this paper are to identify -by using a descriptive research approach- what are the modification that went into the city´s public spaces to reach their current form and how did the residents react to those measurements. The methods of the analysis will use the critical overview, starts by explaining the development of Beirut urban forms, then discuss the renovation methods adopted by Solidere, and conclude with the correlations between the final form of the public spaces and the social reception of the modification renovation process. This article will benefit the researchers and policymakers determine the expected social results of public spaces renovation in cases that simulate the Beirut case. Keywords: Public space renovation, Beirut central district, redevelopment, post-war construction. Introduction: The singularity about the Lebanese case is that the city went through many different conflicts and civil wars, which were the reasons to go through rebuilding and rehabilitation, done by many public and private organizations and governance. The main and direct reason for Beirut deterioration, especially in the traditional city´s centre, was the civil war between 1975-1990, and by the end of the war, the actions towards the rebuilding and the preserving of the heritage were the major concerns of the politicians, architects, and urbanists. -

FC-Micronesia.Pdf

The Federated States of Micronesia DIRK ANTHONY BALLENDORF 1 history and development of federalism Micronesia is a collection of island groups in the Pacific Ocean comprised of four major clusters: the Marianas, Carolines, Marshalls, and Gilberts (now known as Kiribati). The Federated States of Micronesia (fsm) is part of the Caroline island archipelago. The fsm consists of the island groups of Chuuk (formerly Truk), Yap, Pohnpei (formerly Ponape) and Kosrae – it is thus a subset of Micronesia writ large. The total land area of the fsm is approximately 700 km, but the islands are spread over 2.5 million km. It has a population of approximately 108,000 people. The history of Micronesia is one of almost continuous exploitation since Ferdinand Magellan first landed briefly in Guam in 1521. Four successive colonial administrations – Spanish, 1521 to 1898; German, 1899 to 1914; Japanese, 1914 to 1944; and American, 1944 to indepen- dence in 1986 – have controlled the many small islands of Micronesia. In 1947, the United States was assigned administration of Microne- sia under a United Nations Trusteeship Agreement. Like previous co- lonial administrations, the American administration was centralized, with Saipan in the northern Marianas as the capital. The Micronesian peoples were divided into six separate administrative districts: Mari- anas, Yap, Palau, Truk (now Chuuk), Ponape (now Pohnpei), and the Marshalls, and they remained largely self-sufficient and isolated from the rest of the world. In 1977, a seventh district, Kosrae, was created from a division of the Ponape district. 217 Federated States of Micronesia Minimal attention was paid by both the United States and the United Nations to US obligations under the un Charter until a un mission to the area during the Kennedy administration drew attention to an extensive list of local complaints. -

Geographical Characteristics of the State

Geographical Characteristics of the State The Cultural Mosaic Fellman, and Notes from D.J. Zeigler of Old Dominion Vocab Review • State • Sovereignty • Nation • Nation-state • Binational or Multinational • Stateless Nation • Nationalism Territoriality • The modern state is an example of a common human tendency: the need to belong to a larger group that controls its own piece of the earth, its own territory. • This is called territoriality: a cultural strategy that uses power to control area and communicate that control, subjugating inhabitants and acquiring resources. Shapes of States • Compact States – Efficient – Theoretically round – Capital in center – Shortest possible boundaries to defend – Improved communications – Ex. Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Poland, Uraguay Shapes of States • Prorupted States – w./large projecting extension – Sometimes natural – Sometimes to gain a resource or advantage, such as to reach water, create a buffer zone – Ex. Thailand, Myanmar, Namibia, Mozambique, Cameroon, Congo Shapes of States • Elongated States – States that are long and narrow – Suffer from poor internal communication – Capital may be isolated – Ex. Chile, Norway, Vietnam, Italy, Gambia Shapes of States • Fragmented States – Several discontinuous pieces of territory – Technically, all states w/off shore islands – Two kinds: separated by water & separated by an intervening state – Exclave – – Ex. Indonesia, USA, Russia, Philippines Shapes of States • Perforated States – A country that completely surrounds another state – Enclave – the surrounded territory – Ex. Lesotho/South Africa, San Marino & Vatican City/Italy Enclaves and exclaves • An enclave is an area surrounded by a country but not ruled by it. – It can be self-governing or an exclave of another country. Example-- Lesotho – Can be problematic for the surrounding country. -

The Laws on the Ethnic Minority Autonomous Regions in China: Legal Norms and Practices Haiting Zhang

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 9 Article 3 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2012 2012 The Laws on the Ethnic Minority Autonomous Regions in China: Legal Norms and Practices Haiting Zhang Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Haiting Zhang The Laws on the Ethnic Minority Autonomous Regions in China: Legal Norms and Practices, 9 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 249 (2012). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol9/iss2/3 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LAWS ON THE ETHNIC MINORITY AUTONOMous REGIONS IN CHINA: LEGAL NoRMS AND PRACTICES Haiting Zhang t I. Introduction... ............................ 249 II. Regulated Autonomous Powers of the Ethnic Minority Autonomous Regions.................................. 251 A. Autonomous Legislation Powers ....................... 252 B. Special Personnel Arrangements ....................... 252 C. Other Autonomous Powers .......................... 253 III. Problems in the Operation of the Regional Ethnic Autonomous System: The Gap Between Law and Practice ................. 254 A. Local Governmental Nature of the Autonomous Agencies ... 254 B. The Tale of Regional Autonomy Regulations: Insufficient Exercise of the Autonomous Legislation Power ............ 255 C. Behind the Personnel Arrangement: Party Politics and the Ethnic Minority Regional Autonomy ................... 257 D. The Vulnerable Autonomy............................ 259 E. The Economic Gap and the Natural Resource Exploitation Issue .......................................... 260 IV. Seeking Legal Guarantees: Improving the Exercise of the Autonomous Powers..........................................