Note Gave Me the Liberty to Adjust the Topic Mind, the General Requested To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book-91249.Pdf

THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? By SHINA L. F. AMACHIGH " Bachelor of Arts Ahmadu Bello University Samaru-Zaria, Nigeria 1979 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Col lege of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1986 THE MILITARY IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979): CORRECTIVE AGENT OR MERE USURPER OF POWER? Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College 1251198 i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My foremost thanks go to my heavenly Father, the Lord Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit for the completion of this study. Thank you, Dr. Lawler (committee chair), for your guidance and as sistance and for letting me use a dozen or so of your personal textbooks throughout the duration of this study. Appreciation is also expressed to the other committee members, Drs. von Sauer and Sare, for their in valuable assistance in preparation of the final manuscript. Thank you, Ruby and Amen (my wife and son) for not fussing all the times I had to be 11 gone again. 11 I love you. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I • INTRODUCTION Backqround 1 The Problem 2 Thesis and Purpose 2 Analytical Framework and Methodology 3 I I. REVIEW OF THEORETICAL LITERATURE 5 The Ataturk Model ....• 16 The Origins of Military Intervention 18 Africa South of the Sahara .... 20 I II. BRIEF HISTORY OF MILITARY INVOLVEMENT IN NIGERIAN POLITICS (1966-1979) 23 IV. THE PROBLEM OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION 29 British Colonialism and National Inte- gration in Nigeria .... -

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

Downloaded August 21, 2016

ETHNO-RELIGIOUS CONFLICT AND SETTLEMENT DYNAMICS IN PLATEAU STATE, NIGERIA, 1994-2012 BY ONYEKACHI ERNEST NNABUIHE B.A. (Imo), M.A. (Ibadan) A Thesis in PEACE and CONFLICT STUDIES Submitted to the Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies, in partial fulfilment for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN SEPTEMBER 2016 UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY i ABSTRACT Persistent communal conflicts in Plateau State underscore the differences between ethno-religious identities and aggravated segregation in human settlements. Existing studies on ethno-religious conflict have focused on colonial segregated settlement policy otherwise known as the Sabon Gari. These studies have neglected settlement dynamics as both cause and effect of ethno-religious conflicts. This study, therefore, interrogated the complex interaction between ethno-religious conflict and settlement dynamics in Plateau State. This is with a view to showing how conflicts structure and restructure settlements and their implications for inter-group relations, group mobilisation and infrastructural development. The study adopted Lawler‘s Relational theory and case study research design. Respondents were purposively selected from four Local Government Areas comprising Jos North, Jos South, Barkin- Ladi and Riyom. Primary data were collected through 46 in-depth interviews from twelve neighbourhood leaders, eleven ethno-religious group leaders, three members of civil society organisations, four estate managers, two security officials, two academics and twelve youth leaders. A total of six Focus Group Discussions were held: one each with Afizere, Anaguta and Hausa ethnic groups in Jos North, Berom in Jos South, Igbo in Barkin-Ladi and Fulani in Riyom. Non-participant observation method was also employed. -

Accredited Observer Groups/Organisations for the 2011 April General Elections

ACCREDITED OBSERVER GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS FOR THE 2011 APRIL GENERAL ELECTIONS Further to the submission of application by Observer groups to INEC (EMOC 01 Forms) for Election Observation ahead of the April 2011 General Elections; the Commission has shortlisted and approved 291 Domestic Observer Groups/Organizations to observe the forthcoming General Elections. All successful accredited Observer groups as shortlisted below are required to fill EMOC 02 Forms and submit the full names of their officials and the State of deployment to the Election Monitoring and Observation Unit, INEC. Please note that EMOC 02 Form is obtainable at INEC Headquarters, Abuja and your submissions should be made on or before Friday, 25th March, 2011. S/N ORGANISATION LOCATION & ADDRESS 1 CENTER FOR PEACEBUILDING $ SOCIO- HERITAGE HOUSE ILUGA QUARTERS HOSPITAL ECONOMIC RESOURCES ROAD TEMIDIRE IKOLE EKITI DEVELOPMENT(CEPSERD) 2 COMMITTED ADVOCATES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEV SUITE 18 DANOVILLE PLAZA GARDEN ABUJA &YOUTH ADVANCEMENT FCT 3 LEAGUE OF ANAMBRA PROFESSIONALS 86A ISALE-EKO WAY DOLPHIN – IKOYI 4 YOUTH MOVEMENT OF NIGERIA SUITE 24, BLK A CYPRIAN EKWENSI CENTRE FOR ARTS & CULTURE ABUJA 5 SCIENCE & ECONOMY DEV. ORG. SUITE KO5 METRO PLAZA PLOT 791/992 ZAKARIYA ST CBD ABUJA 6 GLOBAL PEACE & FORGIVENESS FOUNDATION SUITE A6, BOBSAR COMPLEX GARKI 7 CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC ENRICHMENT 2 CASABLANCA ST. WUSE 11 ABUJA 8 GREATER TOMORROW INITIATIVE 5 NSIT ST, UYO A/IBOM 9 NIG. LABOUR CONGRESS LABOUR HOUSE CBD ABUJA 10 WOMEN FOR PEACE IN NIG NO. 4 MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY KADUNA 11 YOUTH FOR AGRICULTURE 15 OKEAGBE CLOSE ABUJA 12 COALITION OF DEMOCRATS FOR ELECTORAL 6 DJIBOUTI CRESCENT WUSE 11, ABUJA REFORMS 13 UNIVERSAL DEFENDERS OF DEMOCRACY UKWE HOUSE, PLOT 226 CENSUS CLOSE, BABS ANIMASHANUN ST. -

Policy Levers in Nigeria

CRISE Policy Context Paper 2, December 2003 Policy Levers in Nigeria By Ukoha Ukiwo Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, CRISE Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Executive Summary This paper identifies some prospective policy levers for the CRISE programme in Nigeria. It is divided into two parts. The first part is a narrative of the political history of Nigeria which provides the backdrop for the policy environment. In the second part, an attempt is made to identify the relevant policy actors in the country. Understanding the Policy Environment in Nigeria The policy environment in Nigeria is a complex one that is underlined by its chequered political history. Some features of this political history deserve some attention here. First, despite the fact that prior to its independence Nigeria was considered as a natural democracy because of its plurality and westernized political elites, it has been difficult for the country to sustain democratic politics. The military has held power for almost 28 years out of 43 years since Nigeria became independent. The result is that the civic culture required for democratic politics is largely absent both among the political class and the citizenry. Politics is construed as a zero sum game in which the winner takes all. In these circumstances, political competition has been marked by political violence and abandonment of legitimacy norms. The implication of this for the policy environment is that formal institutions and rules are often subverted leading to the marginalization of formal actors. During the military period, the military political class incorporated bureaucrats and traditional rulers in the process of governance. -

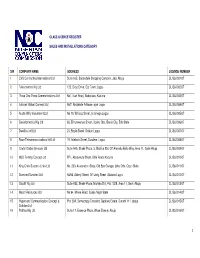

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

An Assessment of Civil Military Relations in Nigeria As an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007

AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 BY MOHAMMED LAWAL TAFIDA DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA JUNE 2015 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled An Assessment of Civil-Military Relations in Nigeria as an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007 has been carried out and written by me under the supervision of Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi, Dr. Mohamed Faal and Professor Paul Pindar Izah in the Department of Political Science and International Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria. The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided in the work. No part of this dissertation has been previously presented for another degree programme in any university. Mohammed Lawal TAFIDA ____________________ _____________________ Signature Date CERTIFICATION PAGE This thesis entitled: AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science of the Ahmadu Bello University Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi ___________________ ________________ Chairman, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Dr. Mohamed Faal________ ___________________ _______________ Member, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Professor Paul Pindar Izah ___________________ -

22 Adjustment, Political Transition, and Tiie

22 UFAHAMU ADJUSTMENT, POLITICAL TRANSITION, AND TIIE ORGANIZATION OF MILITARY POWER IN NIGERIA by Julius 0. Ihonvbere Now, soldiers are part of national problems, rather than problem solvers. And suddenly soldiers are beginning to realize how their thirst for power could plunge their nations into crisis.... In Nigeria, the army authorities are beginning to come to terms with the dangers that the army ironically poses to the nation. t If there is any institution to be least respected in Nigeria, it is the Nigerian army. How could one explain a situation where semi-illiterates whose only qualification is their unguarded accessibility to weapons, want to hold the entire country to ransom?2 With the decline in oil revenues, the closure of credit lines, mounting foreign debts and debt service ratios, and inability to manage an internal economic crisis, the Nigerian government, under General Ibrahim Babangida, had no alternative to adopting a structural adjustment program in 1986. The components of the adjustment program have not been different from those prescribed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank for other "debt distressed" and crisis-ridden African states. It has included policies of desubsidization, deregulation, privatization, retrenchment of workers, and political control of opposition. Nigeria's adjustment program has achieved very lirtle.3 True, a new realism has taken over the society with increasing economic contraction and the gradual rolling back of the state. Yet, at the level of concrete economic achievement, there has been very little to show for the harsh policies imposed on the people.4 The failure, or rather the limited achievement of the adjustment program, can be attributed to a range of internal and external factors. -

The Venus Medicare Hospital Directory

NATIONWIDE PROVIDER DIRECTORY CATEGORY 1 HOSPITALS S/N STATE CITY/TOWN/DISTRICT HEALTHCARE PROVIDER ADDRESS TERMS & CONDITIONS SERVICES Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, 1 FCT/ABUJA CENTRAL AREA Limi Hospital & Maternity Plot 541Central District, Behind NDIC/ICPC HQ, Abuja Nil Internal Medicine Primary, Int. Med, Paediatrics,O&G, GARKI Garki Hospital Abuja Tafawa Balewa Way, Area 3, Garki, Abuja Private Wards not available. Surgery,Dermatology Amana Medical Centre 5 Ilorin str, off ogbomosho str,Area 8, Garki Nil No.5 Plot 802 Malumfashi Close, Off Emeka Anyaoku Strt, Alliance Clinics and Services Area 11 Nil Primary, Int. Med, Paediatrics Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine Dara Medical Clinics Plot 202 Bacita Close, off Plateau Street, Area 2 Nil Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine Sybron Medical Centre 25, Mungo Park Close, Area 11, Garki, Abuja Nil Primary, O&G, Paediatrics,Int Medicine, Gen Guinea Savannah Medical Centre Communal Centre, NNPC Housing Estate, Area II, Garki Nil Surgery, Laboratory Bio-Royal Hospital Ltd 11, Jebba Close, Off Ogun Street, Area 2, Garki Nil Primary, Surgery, Paediatrics. Primary, Family Med, O & G, Gen Surgery, Royal Specialist Hospital 2 Kukawa Street, Off Gimbiyan Street Area 11, Garki, Abuja Nil Urology, ENT, Radiology, Paediatrics No.4 Ikot Ekpene Close, Off Emeka Anyaoku Street Crystal Clinics (opposite National Assembly Clinic) Garki Area 11 Nil Primary, O&G, Paediatrics, Internal Medicine, Surgery Model Care Hospital & Consultancy Primary, Paediatrics, Surgery and ENT Limited No 5 Jaba Close, off Dunukofia Street by FCDA Garki, Abuja Nil Surgery Primary, O&G, General Surgery, Paediatrics, GARKI II Fereprod Medical Centre Obbo Crescent, off Ahmadu Bello Way, Garki II Nil Internal Medicine Holy Trinity Hospital 22 Oroago Str, by Ferma/Old CBN HQ, Garki II Nil Primary only. -

Shippers Registration Form

FORM No: NSC/SRS/97/0030/II NIGERIAN SHIPPERS’ COUNCIL (Established by CAP 327 of Laws of the Federation of Nigeria) MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION FORM Please return after completion to: TYPE OF MEMBERSHIP REQUIRED (Tick One) The Registrar, CORPORATE (Limited Liability Companies, PLCs etc.) Shippers' Registration Scheme, Nigerian Shippers’ Council, TRADE GROUP / ASSOCIATION (commodity groups, 4, Park Lane, Apapa, chambers of commerce, recognised business groups) P. M. B. 50617, Ikoyi, Lagos. BUSINESS NAMES (own name, partnerships, business Tel: 01 – 5458813-14 names) E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.shipperscouncil.com PUBLIC AGENCY (Federal/State/Local Government organisations, parastatals and companies etc. ) OR: Any Nigerian Shippers’ Council office nearest to you. ASSOCIATE (potential shippers, clearing & forwarding (Please see reverse side for addresses) companies, insurance companies, banks, law firms etc.) APPLICANT SHIPPER’S DATA NAME_________________________________________________________________________________________ (Name of Company / Group /Business Names / Agency / Associate to be registered) ADDRESS_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ (Street Name) CITY_____________________ STATE_____________________P. O. BOX___________________P. M. B__________________________ TELEPHONE________________________ FAX_________________________E-MAIL_________________________________ CONTACT PERSON___________________________________________DESIGNATION___________________________________________ -

Click Here to Download

AHISTORYOFNIGERIA Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country and the world’s eighth largest oil producer, but its success has been undermined in recent decades by ethnic and religious conflict, political instability, rampant official corruption, and an ailing economy. Toyin Falola, a leading historian intimately acquainted with the region, and Matthew Heaton, who has worked extensively on African science and culture, combine their expertise to explain the context to Nigeria’s recent troubles, through an exploration of its pre-colonial and colonial past and its journey from independence to statehood. By exami- ning key themes such as colonialism, religion, slavery, nationalism, and the economy, the authors show how Nigeria’s history has been swayed by the vicissitudes of the world around it, and how Nigerians have adapted to meet these challenges. This book offers a unique portrayal of a resilient people living in a country with immense, but unrealized, potential. toyin falola is the Frances Higginbotham Nalle Centennial Professor in History at the University of Texas at Austin. His books include The Power of African Cultures (2003), Economic Reforms and Modernization in Nigeria, 1945–1965 (2004), and A Mouth Sweeter than Salt: An African Memoir (2004). matthew m. heaton is a Patrice Lumumba Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. He has co-edited multiple volumes on health and illness in Africa with Toyin Falola, including HIV/AIDS, Illness and African Well-Being (2007) and Health Knowledge and Belief Systems in Africa (2007). A HISTORY OF NIGERIA TOYIN FALOLA AND MATTHEW M. HEATON University of Texas at Austin CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521862943 © Toyin Falola and Matthew M.