Policy Levers in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa? DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS BUT NO DEMOCRACY Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos cahiers & conférences travaux & recherches les études The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non- profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. The Sub-Saharian Africa Program is supported by: Translated by: Henry Kenrick, in collaboration with the author © Droits exclusivement réservés – Ifri – Paris, 2010 ISBN: 978-2-86592-709-8 Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27 rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – France 1000 Bruxelles – Belgique Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tél. : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Internet Website : Ifri.org Summary Sub-Saharan African hopes of democratization raised by the end of the Cold War and the decline in the number of single party states are giving way to disillusionment. -

Newsletter Igbo Studies Association

NEWSLETTER IGBO STUDIES ASSOCIATION VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 ISSN: 2375-9720 COVER PHOTO CREDIT INCHSERVICES.COM PAGE 1 VOLUME 1, FALL 2014 EDITORIAL WELCOME TO THE FIRST EDITION OF ISA NEWS! November 2014 Dear Members, I am delighted to introduce the first edition of ISA Newsletter! I hope your semester is going well. I wish you the best for the rest of the academic year! I hope that you will enjoy this maiden issue of ISA Newsletter, which aims to keep you abreast of important issue and events concerning the association as well as our members. The current issue includes interesting articles, research reports and other activities by our Chima J Korieh, PhD members. The success of the newsletter will depend on your contributions in the forms of President, Igbo Studies Association short articles and commentaries. We will also appreciate your comments and suggestions for future issues. The ISA executive is proud to announce that a committee has been set up to work out the modalities for the establishment of an ISA book prize/award. Dr Raphael Njoku is leading the committee and we expect that the initiative will be approved at the next annual general meeting. The 13th Annual Meeting of the ISA taking place at Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is only six months away and preparations are ongoing to ensure that we have an exciting meet! We can’t wait to see you all in Milwaukee in April. This is an opportunity to submit an abstract and to participate in next year’s conference. ISA is as strong as its membership, so please remember to renew your membership and to register for the conference, if you have not already done so! Finally, we would like to congratulate the newest members of the ISA Executive who were elected at the last annual general meeting in Chicago. -

Accredited Observer Groups/Organisations for the 2011 April General Elections

ACCREDITED OBSERVER GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS FOR THE 2011 APRIL GENERAL ELECTIONS Further to the submission of application by Observer groups to INEC (EMOC 01 Forms) for Election Observation ahead of the April 2011 General Elections; the Commission has shortlisted and approved 291 Domestic Observer Groups/Organizations to observe the forthcoming General Elections. All successful accredited Observer groups as shortlisted below are required to fill EMOC 02 Forms and submit the full names of their officials and the State of deployment to the Election Monitoring and Observation Unit, INEC. Please note that EMOC 02 Form is obtainable at INEC Headquarters, Abuja and your submissions should be made on or before Friday, 25th March, 2011. S/N ORGANISATION LOCATION & ADDRESS 1 CENTER FOR PEACEBUILDING $ SOCIO- HERITAGE HOUSE ILUGA QUARTERS HOSPITAL ECONOMIC RESOURCES ROAD TEMIDIRE IKOLE EKITI DEVELOPMENT(CEPSERD) 2 COMMITTED ADVOCATES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEV SUITE 18 DANOVILLE PLAZA GARDEN ABUJA &YOUTH ADVANCEMENT FCT 3 LEAGUE OF ANAMBRA PROFESSIONALS 86A ISALE-EKO WAY DOLPHIN – IKOYI 4 YOUTH MOVEMENT OF NIGERIA SUITE 24, BLK A CYPRIAN EKWENSI CENTRE FOR ARTS & CULTURE ABUJA 5 SCIENCE & ECONOMY DEV. ORG. SUITE KO5 METRO PLAZA PLOT 791/992 ZAKARIYA ST CBD ABUJA 6 GLOBAL PEACE & FORGIVENESS FOUNDATION SUITE A6, BOBSAR COMPLEX GARKI 7 CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC ENRICHMENT 2 CASABLANCA ST. WUSE 11 ABUJA 8 GREATER TOMORROW INITIATIVE 5 NSIT ST, UYO A/IBOM 9 NIG. LABOUR CONGRESS LABOUR HOUSE CBD ABUJA 10 WOMEN FOR PEACE IN NIG NO. 4 MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY KADUNA 11 YOUTH FOR AGRICULTURE 15 OKEAGBE CLOSE ABUJA 12 COALITION OF DEMOCRATS FOR ELECTORAL 6 DJIBOUTI CRESCENT WUSE 11, ABUJA REFORMS 13 UNIVERSAL DEFENDERS OF DEMOCRACY UKWE HOUSE, PLOT 226 CENSUS CLOSE, BABS ANIMASHANUN ST. -

Nigeria: the Challenge of Military Reform

Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform Africa Report N°237 | 6 June 2016 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Long Decline .............................................................................................................. 3 A. The Legacy of Military Rule ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Military under Democracy: Failed Promises of Reform .................................... 4 1. The Obasanjo years .............................................................................................. 4 2. The Yar’Adua and Jonathan years ....................................................................... 7 3. The military’s self-driven attempts at reform ...................................................... 8 III. Dimensions of Distress ..................................................................................................... 9 A. The Problems of Leadership and Civilian Oversight ................................................ -

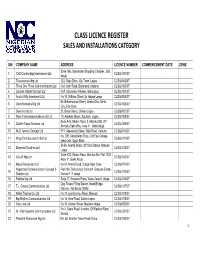

Class Licence Register Sales and Installations Category

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENCE NUMBER COMMENCEMENT DATE ZONE Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd CL/S&I/001/07 Abuja 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd CL/S&I/006/07 City, Edo State 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd CL/S&I/009/07 Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd CL/S&I/011/07 Ijebu Ode, Ogun State 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd CL/S&I/012/07 Lagos Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd CL/S&I/013/07 Area 11, Garki Abuja 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, 15 CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd Durumi 111, abuja 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 Opp Texaco Filing Station, Head Bridge, 17 T.J. -

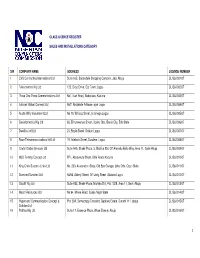

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Nigeria Nigeria at a Glance: 2005-06

Country Report Nigeria Nigeria at a glance: 2005-06 OVERVIEW The president, Olusegun Obasanjo, and his team face a daunting task in their efforts to push through long-term, sustainable economic reforms in the coming two years. However, the recent crackdown on high-level corruption seems to point to the president!s determination to use his final years in power to shake up Nigeria!s political system and this should help the reform process. Given the background of ethnic and religious divisions, widespread poverty, and powerful groups with vested interests in maintaining the current status quo, there is a risk that the reform drive, if not properly managed, could destabilise the country. Strong growth in the oil and agricultural sectors will ensure that real GDP growth remains reasonably high, at about 4%, in 2005 and 2006, but the real challenge will be improving performance in the non-oil sector, which will be a crucial part of any real attempt to reduce poverty in the country. Key changes from last month Political outlook • There have been no major changes to the Economist Intelligence Unit!s political outlook. Economic policy outlook • There have been no major changes to our economic policy outlook. Economic forecast • New external debt data for 2003 show that the proportion of Nigeria!s debt denominated in euros was much higher than previously estimated. Owing to the weakness of the US dollar against the euro since 2003, this has pushed up Nigeria!s debt stock substantially, to US$35bn at the end of 2003. Despite limited new lending, mainly from multilateral lenders, we estimate that further currency revaluations and the addition of interest arrears to the short-term debt stock will push total external debt up to US$39.5bn by the end of 2006. -

Herdsmen Terror in Nigeria: the Identity Question and Classification Dilemma

American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2020 American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-03, Issue-03, pp 10-25 March-2020 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access Herdsmen Terror In Nigeria: The Identity Question And Classification Dilemma PROF. CYRIL ANAELE Department Of History & Diplomatic Studies Salem University, Lokoja – Nigeria Phone: +23408068683303 *Corresponding Author: PROF. CYRIL ANAELE ABSTRACT:- Nigeria in recent years is a home to diversities of terror restricted to specific geo-political zones. Of all these terrors, non cuts across the country as that of the herdsmen. The herdsmen like invading Mongols leave deaths and destructions in their wake. Certainly and troubling too, is the government’s unwillingness to classify them as terrorist gang, but instead is dangling on classification dilemma. This too, has created identity question, on who actually are these herdsmen and their exact identity. Government has chosen to identify them as herdsmen and sees their killings as precipitated by conflict over land, between herders and farmers. The paper rejects government’s position that the herdsmen are not terrorists; and their activities as conflict over grazing land. To the contrary, the paper argues that the herdsmen are Fulani (in and outside Nigeria) hundred percent Muslim, and their terror fundamentally linked to causes beyond competition over land. It adopts the Samuel Huntington (1996) and Healy “Multiple Factor” theory for its theoretical framework. In methodology, it relies on primary and secondary data, using historical unit analysis for the presentation. The major findings of the study are, (i) the herdsmen are Fulani, (ii) their orchestrated violence across Nigeria is naked terrorism anxiously waiting to be listed as domestic terrorism before it morphoses into international terror (iii)the overall objective is Islamisation and Fulanisation of Nigeria. -

![Human Rights and Democracy [In Nigeria]: Agenda for a New Era](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0367/human-rights-and-democracy-in-nigeria-agenda-for-a-new-era-1320367.webp)

Human Rights and Democracy [In Nigeria]: Agenda for a New Era

AfriHeritage Occasional Paper Vol 1. No1. 2019 AfriHeritage Occasional Paper Vol 1. No1. 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRACY [IN NIGERIA]: AGENDA FOR A NEW ERA By Chidi Anselm Odinkalu 1 AfriHeritage Occasional Paper Vol 1. No1. 2019 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. MEDIATING MULTI-DIMENSIONAL POLARITIES: IN SEARCH OF OUR BIG IDEA . 5 (a) Democracy, Counting and Accounting: The Idea of Political Numeracy ........... 8 (b) Democracy: The idea of Legitimacy .............................................................................. 11 (c) Human Rights: The Idea of Political Values ................................................................ 16 (d) Democracy and Digital Frisson: The Idea of Good Civic Manners ..................... 21 (a) Mis-Managing Diversity & Institutionalising Discrimination ............................... 28 (b) A Country that Cannot Count ......................................................................................... 34 (c) The Destruction of Accountability Institutions .......................................................... 40 (d) Legitimising Illegitimacy .................................................................................................... 44 4. ADDRESSING NIGERIA’S MULTIPLE CRISES OF STATEHOOD AND FRAGMENTATION -

Jesus, the Sw, and Christian-Muslim Relations in Nigeria

Conflicting Christologies in a Context of Conflicts: Jesus, the sw, and Christian-Muslim Relations in Nigeria Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum religionum (Dr. rer. rel.) der Theologischen Fakultät der Universität Rostock vorgelegt von Nguvugher, Chentu Dauda, geb. am 10.10.1970 in Gwakshesh, Mangun (Nigeria) aus Mangun Rostock, 21.04.2010 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Klaus Hock Chair: History of Religions-Religion and Society Faculty of Theology, University of Rostock, Germany Examiners Dr. Sigvard von Sicard Honorary Senior Research Fellow Department of Theology and Religion University of Birmingham, UK Prof. Dr. Frieder Ludwig Seminarleiter Missionsseminar Hermannsburg/ University of Goettingen, Germany Date of Examination (Viva) 21.04.2010 urn:nbn:de:gbv:28-diss2010-0082-2 Selbständigkeitserklärung Ich erkläre, dass ich die eingereichte Dissertation selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die von mir angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und die den benutzten Werken wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Statement of Primary Authorship I hereby declare that I have written the submitted thesis independently and without help from others, that I have not used other sources and resources than those indicated by me, and that I have properly marked those passages which were taken either literally or in regard to content from the sources used. ii CURRICULUM VITAE CHENTU DAUDA NGUVUGHER Married, four children 10.10.1970 Born in Gwakshesh, Mangun, Plateau -

Africa Confidential

5 March 1999 Vol 40 No 5 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL NIGERIA 2 NIGERIA Virtual voters UN and European Union monitors Soldier go, soldier come reckoned that Obasanjo's election President-elect Obasanjo's greatest challenge will be his plans to victory was seriously flawed but reform the military and end the putschist mentality 'generally reflected the will of the people'. Translated, that means The Nigerian conundrum - ‘it takes a soldier to end army rule’ - is to be tested again. General both sides rigged the vote but Olusegun Obasanjo, the choice of most army officers and the Western powers, was dubbed PDP Obasanjo's party was better at it (Pre-Determined President) - the acronym of his People’s Democratic Party. The 27 February and he would have won anyway. presidential election indeed had a pre-determined feel to it (see Box). But that’s not entirely surprising when Obasanjo faced an improbable coalition of erstwhile supporters of 1993 poll winner SOUTH AFRICA/USA 3 Moshood Abiola in the Alliance for Democracy and the All People’s Party (dubbed the Abacha People’s Party because so many of the late dictator’s acolytes had joined it). Within hours of his Transatlantic tryst victory, Obasanjo started choosing the transition committee which is to handle policy and appointments Washington now has closer up to the formal handover to civilian rule on 29 May. His hotel suite in Abuja has been overflowing relations with the ANC government with well-wishers and office-seekers. than with any other in Africa, A paid-up Nigerian nationalist, Obasanjo makes his priority to build a team that brings in the including Egypt and Morocco.