Nigeria Nigeria at a Glance: 2005-06

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combating Corruption in Nigeria: a Critical Appraisal of the Laws, Institutions, and the Political Will Osita Nnamani Ogbu

Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 6 2008 Combating Corruption in Nigeria: A Critical Appraisal of the Laws, Institutions, and the Political Will Osita Nnamani Ogbu Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey Part of the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Ogbu, Osita Nnamani (2008) "Combating Corruption in Nigeria: A Critical Appraisal of the Laws, Institutions, and the Political Will," Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law: Vol. 14: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey/vol14/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ogbu: Combating Corruption in Nigeria COMBATING CORRUPTION IN NIGERIA: A CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE LAWS, INSTITUTIONS, AND THE POLITICAL WILL OSITA NNAMANI OGBU· I. INTRODUCTION Corruption is pervasive and widespread in Nigerian society. It has permeated all facets of life, and every segment of society is involved. In recent times, Nigeria has held the unenviable record of being considered one of the most corrupt countries among those surveyed I. The Political Bureau, set up under the Ibrahim Babangida regime, summed up the magnitude of corruption in Nigeria as follows: It [corruption] pervades all strata of the society. From the highest level of the political and business elites to the ordinary person in the village. Its multifarious manifestations include the inflation of government contracts in return for kickbacks; fraud and falsification of accounts in the public service; examination * Senior Lecturer, and Ag. -

Le Nigeria Et La Suisse, Des Affaires D'indépendance

STEVE PAGE Le Nigeria et la Suisse, des affaires d’indépendance Commerce, diplomatie et coopération 1930–1980 PETER LANG Analyser les rapports économiques et diplomatiques entre le Nigeria et la Suisse revient à se pencher sur des méca- nismes peu connus de la globalisation: ceux d’une relation Nord-Sud entre deux puissances moyennes et non colo- niales. Pays le plus peuplé d’Afrique, le Nigeria semblait en passe de devenir, à l’aube de son indépendance, une puissance économique continentale. La Suisse, comme d’autres pays, espérait profiter de ce vaste marché promis à une expansion rapide. Entreprises multinationales, diplo- mates et coopérants au développement sont au centre de cet ouvrage, qui s’interroge sur les motivations, les moyens mis en œuvre et les impacts des activités de chacun. S’y ajoutent des citoyens suisses de tous âges et de tous mi- lieux qui, bouleversés par les images télévisées d’enfants squelettiques durant la « Guerre du Biafra » en 1968, en- treprirent des collectes de fonds et firent pression sur leur gouvernement pour qu’il intervienne. Ce livre donne une profondeur éclairante aux relations Suisse – Nigeria, ré- cemment médiatisées sur leurs aspects migratoires, ou sur les pratiques opaques de négociants en pétrole établis en Suisse. STEVE PAGE a obtenu un doctorat en histoire contempo- raine de l’Université de Fribourg et fut chercheur invité à l’IFRA Nigeria et au King’s College London. Il poursuit des recherches sur la géopolitique du Nigeria. www.peterlang.com Le Nigeria et la Suisse, des affaires d’indépendance STEVE PAGE Le Nigeria et la Suisse, des affaires d’indépendance Commerce, diplomatie et coopération 1930–1980 PETER LANG Bern · Berlin · Bruxelles · Frankfurt am Main · New York · Oxford · Wien Information bibliographique publiée par «Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek» «Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek» répertorie cette publication dans la «Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e»; les données bibliographiques détaillées sont disponibles sur Internet sous ‹http://dnb.d-nb.de›. -

Accredited Observer Groups/Organisations for the 2011 April General Elections

ACCREDITED OBSERVER GROUPS/ORGANISATIONS FOR THE 2011 APRIL GENERAL ELECTIONS Further to the submission of application by Observer groups to INEC (EMOC 01 Forms) for Election Observation ahead of the April 2011 General Elections; the Commission has shortlisted and approved 291 Domestic Observer Groups/Organizations to observe the forthcoming General Elections. All successful accredited Observer groups as shortlisted below are required to fill EMOC 02 Forms and submit the full names of their officials and the State of deployment to the Election Monitoring and Observation Unit, INEC. Please note that EMOC 02 Form is obtainable at INEC Headquarters, Abuja and your submissions should be made on or before Friday, 25th March, 2011. S/N ORGANISATION LOCATION & ADDRESS 1 CENTER FOR PEACEBUILDING $ SOCIO- HERITAGE HOUSE ILUGA QUARTERS HOSPITAL ECONOMIC RESOURCES ROAD TEMIDIRE IKOLE EKITI DEVELOPMENT(CEPSERD) 2 COMMITTED ADVOCATES FOR SUSTAINABLE DEV SUITE 18 DANOVILLE PLAZA GARDEN ABUJA &YOUTH ADVANCEMENT FCT 3 LEAGUE OF ANAMBRA PROFESSIONALS 86A ISALE-EKO WAY DOLPHIN – IKOYI 4 YOUTH MOVEMENT OF NIGERIA SUITE 24, BLK A CYPRIAN EKWENSI CENTRE FOR ARTS & CULTURE ABUJA 5 SCIENCE & ECONOMY DEV. ORG. SUITE KO5 METRO PLAZA PLOT 791/992 ZAKARIYA ST CBD ABUJA 6 GLOBAL PEACE & FORGIVENESS FOUNDATION SUITE A6, BOBSAR COMPLEX GARKI 7 CENTRE FOR ACADEMIC ENRICHMENT 2 CASABLANCA ST. WUSE 11 ABUJA 8 GREATER TOMORROW INITIATIVE 5 NSIT ST, UYO A/IBOM 9 NIG. LABOUR CONGRESS LABOUR HOUSE CBD ABUJA 10 WOMEN FOR PEACE IN NIG NO. 4 MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY KADUNA 11 YOUTH FOR AGRICULTURE 15 OKEAGBE CLOSE ABUJA 12 COALITION OF DEMOCRATS FOR ELECTORAL 6 DJIBOUTI CRESCENT WUSE 11, ABUJA REFORMS 13 UNIVERSAL DEFENDERS OF DEMOCRACY UKWE HOUSE, PLOT 226 CENSUS CLOSE, BABS ANIMASHANUN ST. -

Policy Levers in Nigeria

CRISE Policy Context Paper 2, December 2003 Policy Levers in Nigeria By Ukoha Ukiwo Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, CRISE Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Executive Summary This paper identifies some prospective policy levers for the CRISE programme in Nigeria. It is divided into two parts. The first part is a narrative of the political history of Nigeria which provides the backdrop for the policy environment. In the second part, an attempt is made to identify the relevant policy actors in the country. Understanding the Policy Environment in Nigeria The policy environment in Nigeria is a complex one that is underlined by its chequered political history. Some features of this political history deserve some attention here. First, despite the fact that prior to its independence Nigeria was considered as a natural democracy because of its plurality and westernized political elites, it has been difficult for the country to sustain democratic politics. The military has held power for almost 28 years out of 43 years since Nigeria became independent. The result is that the civic culture required for democratic politics is largely absent both among the political class and the citizenry. Politics is construed as a zero sum game in which the winner takes all. In these circumstances, political competition has been marked by political violence and abandonment of legitimacy norms. The implication of this for the policy environment is that formal institutions and rules are often subverted leading to the marginalization of formal actors. During the military period, the military political class incorporated bureaucrats and traditional rulers in the process of governance. -

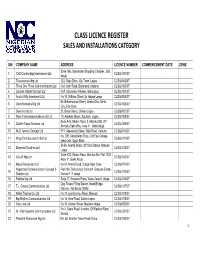

Class Licence Register Sales and Installations Category

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENCE NUMBER COMMENCEMENT DATE ZONE Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd CL/S&I/001/07 Abuja 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd CL/S&I/006/07 City, Edo State 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd CL/S&I/009/07 Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd CL/S&I/011/07 Ijebu Ode, Ogun State 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd CL/S&I/012/07 Lagos Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd CL/S&I/013/07 Area 11, Garki Abuja 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, 15 CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd Durumi 111, abuja 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 Opp Texaco Filing Station, Head Bridge, 17 T.J. -

The Treaty of Pelindaba on the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone

UNIDIR/2002/16 The Treaty of Pelindaba on the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Oluyemi Adeniji UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva, Switzerland NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/2002/16 Copyright © United Nations, 2002 All rights reserved UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.03.0.5 ISBN 92-9045-145-9 CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements . vii Foreword by John Simpson . ix Glossary of Terms. xi Introduction. 1 Chapter 1 Evolution of Global and Regional Non-Proliferation . 11 Chapter 2 Nuclear Energy in Africa . 25 Chapter 3 The African Politico-Military Origins of the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone . 35 Chapter 4 The Transition Period: The End of Apartheid and the Preparations for Negotiations . 47 Chapter 5 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part I): The Harare Meeting . 63 Chapter 6 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part II): The 1994 Windhoek and Addis Ababa Drafting Meetings, and References where Appropriate to the 1995 Johannesburg Joint Meeting . 71 Chapter 7 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part III): Annexes and Protocols . 107 Chapter 8 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part IV): Joint Meeting of the United Nations/OAU Group of Experts and the OAU Inter- Governmental Group, Johannesburg. -

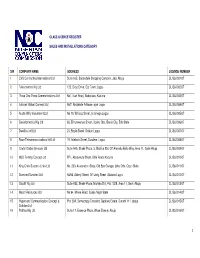

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

(EFCC) ALONG LEADERSHIP REGIMES in NIGERIA Umar, Hassan Sa’Id Department of Public Administration, University of Abuja, Nigeria

Global Journal of Political Science and Administration Vol.3, No.3, pp.1-9, July 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) AN ANALYSIS OF DIFFERENTIAL PERFORMANCES OF THE ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRIMES COMMISSION (EFCC) ALONG LEADERSHIP REGIMES IN NIGERIA Umar, Hassan Sa’id Department of Public Administration, University of Abuja, Nigeria ABSTRACT: One of the greatest enemies of human growth and societal development is corruption. More worrisome is when there is manifestly a deliberate failure to get rid of its spread and existence. This research is a survey type that assessed the perception of Nigerians on possible differential performance of EFCC along leadership regimes. This research is an extraction of a Ph.D thesis that explored both primary and secondary data. The theory of prismatic society provided a frame work for the analysis. The study reveals a differential perception on the performance of the EFCC along leadership regimes. It also shows that president Olusegun (1999-2007) is favorably higher in ranking in the fight against corruption than the YarAdua regime with Goodluck’s administration at lowest ebb of the score. The research concludes that the premise for this leadership cocksureness is the vacuum created by weak institution of governance. This vacuum provides an avenue for tendentious attitudes and despotic inclination to governance. The study recommends inter alia; a need for virile institutions of governance, political culture of discipline and leadership consciousness and conscious national agenda. KEYWORDS: Corruption, Leadership, Performance, Regime, Anticorruption INTRODUCTION The political administration system in Nigeria is said to have been largely influenced by the leadership qualities and disposition of the political head, elected or otherwise. -

Central African Republic – Uncertain Prospects

UNHCR Emergency and Security Service WRITENET Paper No. 14 / 2001 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC – UNCERTAIN PROSPECTS By Paul Melly Independent Researcher, UK Revised May 2002 WriteNet is a Network of Researchers and Writers on Human Rights, Forced Migration, Ethnic and Political Conflict WriteNet is a Subsidiary of Practical Management (UK) E-mail: [email protected] THIS PAPER WAS PREPARED MAINLY ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THE PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT PURPORT TO BE, EITHER EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THE PAPER ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF WRITENET OR UNHCR. ISSN 1020-8429 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction.....................................................................................1 2 Historical and Cultural Background............................................1 3 The Patassé Government and Military Instability......................4 3.1 The Patassé Administration: Political and Economic Tensions ..............4 3.2 The 1996-1997 Mutiny Crisis and Its Consequences................................5 4 The Crisis of 2001 ...........................................................................8 4.1 Failed Coup of May and Aftermath...........................................................8 4.2 The Aftermath and Consequences ...........................................................14 5 Factors Shaping -

Nigeria's Struggle with Corruption Hearing

NIGERIA’S STRUGGLE WITH CORRUPTION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 18, 2006 Serial No. 109–172 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/international—relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27–648PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 21 2002 12:05 Jul 17, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\AGI\051806\27648.000 HINTREL1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, HOWARD L. BERMAN, California Vice Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DAN BURTON, Indiana ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American ELTON GALLEGLY, California Samoa ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BRAD SHERMAN, California PETER T. KING, New York ROBERT WEXLER, Florida STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts RON PAUL, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York DARRELL ISSA, California BARBARA LEE, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon MARK GREEN, Wisconsin SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada JERRY WELLER, Illinois GRACE F. -

From Hell: the Surge of Corruption in Nigeria (1999 – 2007)

Academic Leadership: The Online Journal Volume 9 Article 27 Issue 1 Winter 2011 1-1-2011 From Hell: The urS ge of Corruption in Nigeria (1999 – 2007) Segun Oshewolo J. Olanrewaju Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Oshewolo, Segun and Olanrewaju, J. (2011) "From Hell: The urS ge of Corruption in Nigeria (1999 – 2007)," Academic Leadership: The Online Journal: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 27. Available at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj/vol9/iss1/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Leadership: The Online Journal by an authorized editor of FHSU Scholars Repository. academicleadership.org http://www.academicleadership.org/1360/from-hell-the-surge-of-corruption-in- nigeria-1999-2007/ Academic Leadership Journal Introduction Nigeria is one of the world’s most endowed nations, with abundant human and natural resources. These resources are located in all the states of the federation and exist in commercial quantities (see Ajibewa, 2006:261). The proceeds from these resources have been disproportionately distributed to the disadvantage of the poor population while through the paraphernalia of the presidium of government, the allocation of resources has been done to generously favour the ruling and business elites as well as their cronies. This situation has given rise to the grave issue of inequality in the country. The availability of these resources notwithstanding, Nigeria is still underdeveloped; a condition that has largely been blamed on corruption. -

A Discourse on Accumulation and the Contradictions of Capitalist Development in Nigeria

A Discourse on Accumulation and the Contradictions of Capitalist Development in Nigeria BY: ADELAJA ODUTOLA ODUKOYA B.Sc. (HONS), M.SC POLITICAL SCIENCE (UNILAG) MATRIC. NO. 84090342 Being a Dissertation in the Department of Political Science Submitted to the School of Post-Graduate Studies, University of Lagos in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D). June 2011 1 | P a g e School of Post-Graduate Studies University of Lagos Certification This is to certify that the Thesis A Discourse on Accumulation and the Contradictions of Capitalist Development in Nigeria Submitted to the School of Post-Graduate Studies University of Lagos For the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (P Ph.D) in Political Science is a record of original research carried out By Adelaja Odutola Odukoya B.Sc. (Hons.), M.Sc. Political Science (UNILAG) Matriculation No: 840903042 Author‟s Name Signature Date 1st Supervisor‟s Name Signature Date 2nd Supervisor‟s Name Signature Date 1st Internal Examiner Signature Date 2nd Internal Examiner Signature Date External Examiner Signature Date SPGS Representative Signature Date ii | P a g e DEDICATION To the memory of my beloved father, Pa. Erastus Ebun-Oluwa Omotayo Odukoya iii | P a g e ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I discovered in the course of this study that writing a dissertation is a process of intangible accumulation, not capital accumulation that is the subject-matter of this study. Similarly, writing this acknowledgement is an opportunity for documenting my indebtedness, as well as my sincere appreciation for acts of kindness, assistance, friendships, insightful contributions, critiques and other debts incurred in the process of writing this thesis.