(Re)Presenting Geopolitical and National Identities and at the Same Time, Demonstrating the Fluidity and Contestations of These Constructs1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Is Malvina Hofman? By: Vladimir Čeh

Vladimir Čeh (1946) Владимир Чех (1946) Институт за историју оглашавања је основан 2012. године ради The lnstitute of Advertising History was founded in 2012 to research истраживања и афирмације историје и развоја оглашавања и and raise awareness of the history and development of advertising интегрисаних маркетинг комуникација, њиховог утицаја на културу and integrated marketing communications, of their impact оn the way живљења и њихове промоције. of life and of their promotion. Philologist. After 25 years at Radio Belgrade, Реализацијом пројеката и програма који обухватају проучавање Ву implementing projects and programmes that include the study Филолог. После 25 година рада у Радио he was partner, owner and/or creative director историјских процеса, догађаја, личности и појава, Институт of historical processes, events, personalities and concepts, the Београду био партнер, власник и/или in several advertising agencies. Long-term прикупља, чува, стручно обрађује и приказује јавности lnstitute collects, preserves, expertly treats and presents to the креативни директор у неколико огласних president of the Belgrade branch of the IAA комуникацијске алате и историјску грађу од значаја за развијања public communication tools and historical material important for агенција. Дугогодишњи председник (International Advertising Association), member свести о улози и месту интегрисаних маркетинг комуникација у developing awareness of the role and place of integrated marketing Београдског огранка IAA (International of the IAA world board, president of the Serbian култури живљења. communications in society and culture. Advertising Association), члан светског борда Propaganda Association (UEPS), president of IAA, председник Удружења пропагандиста the UEPS Court of honour. Остваривањем својих циљева Институт реализује, афирмише ln pursuit of its goals, the lnstitute realizes and promotes cooperation Србије (УЕПС), председник Суда части и промовише сарадњу са музејима, архивима, библиотекама, with museums, archives, libraries, professional associations, WHO IS УЕПС-а. -

Roosevelts' Giant Panda Group Installed in William V

News Published Monthly by Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago Vol. 2 JANUARY, 1931 No. 1 ROOSEVELTS' GIANT PANDA GROUP INSTALLED IN WILLIAM V. KELLEY HALL By Wilfred H. Osgood conferences with them at Field Museum be superficial, and it was then transferred Curator, Department of Zoology while the expedition was being organized, to the group which includes the raccoons although it was agreed that a giant panda and allies, one of which was the little panda, The outstanding feature of the William would furnish a most satisfactory climax for or common which is also Asiatic in V. Kelley-Roosevelts Expedition to Eastern panda, their the chance of one was distribution. Still an Asia for Field Museum was the obtaining efforts, getting later, independent posi- considered so small it was best to tion was advocated for in which it became of a complete and perfect specimen of the thought it, make no announcement it when the sole of a peculiar animal known as the giant panda concerning living representative distinct or great panda. In popular accounts this they started. There were other less spec- family of mammals. Preliminary examina- rare beast has been described as an animal tacular animals to be hunted, the obtaining tion of the complete skeleton obtained by with a face like a raccoon, a body like a of which would be a sufficient measure of the Roosevelts seems to indicate that more bear, and feet like a cat. Although these success, so the placing of advance emphasis careful study will substantiate this last view. characterizations are The giant panda is not scientifically accu- a giant only by com- rate, all of them have parison with its sup- some basis in fact, and posed relative, the little it might even be added panda, which is long- that its teeth have cer- tailed and about the tain slight resem- size of a small fox. -

Clara E. Sipprell Papers

Clara E. Sipprell Papers An inventory of her papers at Syracuse University Finding aid created by: - Date: unknown Revision history: Jan 1984 additions, revised (ASD) 14 Oct 2006 converted to EAD (AMCon) Feb 2009 updated, reorganized (BMG) May 2009 updated 87-101 (MRC) 21 Sep 2017 updated after negative integration (SM) 9 May 2019 added unidentified and "House in Thetford, Vermont" (KD) extensively updated following NEDCC rehousing; Christensen 14 May 2021 correspondence added (MRC) Overview of the Collection Creator: Sipprell, Clara E. (Clara Estelle), 1885-1975. Title: Clara E. Sipprell Papers Dates: 1915-1970 Quantity: 93 linear ft. Abstract: Papers of the American photographer. Original photographs, arranged as character studies, landscapes, portraits, and still life studies. Correspondence (1929-1970), clippings, interviews, photographs of her. Portraits of Louis Adamic, Svetlana Allilueva, Van Wyck Brooks, Pearl S. Buck, Rudolf Bultmann, Charles E. Burchfield, Fyodor Chaliapin, Ralph Adams Cram, W.E.B. Du Bois, Albert Einstein, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Ralph E. Flanders, Michel Fokine, Robert Frost, Eva Hansl, Roy Harris, Granville Hicks, Malvina Hoffman, Langston Hughes, Robinson Jeffers, Louis Krasner, Serge Koussevitzky, Luigi Lucioni, Emil Ludwig, Edwin Markham, Isamu Noguchi, Maxfield Parrish, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dane Rudhyar, Ruth St. Denis, Otis Skinner, Ida Tarbell, Howard Thurman, Ridgely Torrence, Hendrik Van Loon, and others Language: English Repository: Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries 222 Waverly Avenue Syracuse, NY 13244-2010 http://scrc.syr.edu Biographical History Clara E. Sipprell (1885-1975) was a Canadian-American photographer known for her landscapes and portraits of famous actors, artists, writers and scientists. Sipprell was born in Ontario, Canada, a posthumous child with five brothers. -

Table of Contents

Vol. 45, No. 1 January 2016 Newsof the lHistoryetter of Science Society Table of Contents From the President: Janet Browne From the President 1 HSS President, 2016-2017 Notes from the Inside 3 Publication of this January 2016 Newsletter provides me in congratulating Angela very warmly on a task Reflections on the Prague a welcome opportunity for the officers of the Society carried out superbly well. Conference “Gendering Science” 4 to wish members a very happy new year, and to thank Lone Star Historians of It is usual at this point in the cycle of Society business our outgoing president Angela Creager most sincerely Science—2015 8 for the incoming president also to write a few forward- for her inspired leadership. Presidents come and go, Lecturing on the History of looking words. As I take up this role it is heartening to but Angela has been special. She brought a unique Science in Unexpected Places: be able to say that I am the eighth female in this position Chronicling One Year on the Road 9 combination of insight, commitment, and sunny good since the Society’s foundation, and the third in a row. A Renaissance in Medieval nature to every meeting of the various committees and The dramatic increase of women in HSS’s structure Medical History 13 phone calls that her position entailed and has been and as speakers and organizers at the annual meeting, Member News 15 an important guide in steering the Society through from the time I first attended a meeting, perhaps a number of structural revisions and essential long- In Memoriam: John Farley 18 reflects a larger recalibration of the field as a whole. -

Anthropological Regionalism at the American Museum of Natural History, 1895–1945

52 Ira Jacknis: ‘America Is Our Field’: Anthropological Regionalism at the American Museum of Natural History, 1895–1945 ‘America Is Our Field’: Anthropological Regionalism at the American Museum of Natural History, 1895–1945 *Ira Jacknis Abstract This article outlines the regional interests and emphases in anthropological collection, research, and display at the American Museum of Natural History, during the first half of the twentieth century. While all parts of the world were eventually represented in the museum’s collections, they came from radically different sources at different times, and for different reasons. Despite his identity as an Americanist, Franz Boas demonstrated a much more ambitious interest in world-wide collecting, especially in East Asia. During the post-Boasian years, after 1905, the Anthropology Department largely continued an Americanist emphasis, but increasingly the museum’s administration encouraged extensive collecting and exhibition for the Old World cultures. For the most part, these collections and exhibits diverged from anthropological concerns, expressing imperialist messages, biological documentation, or artistic display. In thus constituting the ‘stuff’ of an anthropology museum, one can trace the transvaluation of objects, the importance of networks, institutional competition, and the role of disciplinary definitions. Keywords: museum, anthropology, collecting, exhibition, culture areas, American Museum of Natural History Almost by definition, the great metropolitan natural history museums were founded on a problematic relationship to a distant ‘field.’ Wandering through their halls, the visitor is confronted by cultures that are usually far away in space and time.1 As they were developed in the nineteenth century, these natural history museums, parallel to the art museums (Duncan and Wallach 1980), adopted Enlightenment schemes of universal survey. -

Joan of Arc" in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Fall 1975 The Significance of the questrianE Monument "Joan of Arc" in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington Myrna Garvey Eden Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Eden, Myrna Garvey. "The Significance of the questrianE Monument 'Joan of Arc' in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington." The Courier 12.4 (1975): 3-12. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOAN OF ARC Bronze, 11.4 times life. 1915. Riverside Drive and 93rd Street, New York, New York. Anna Hyatt Huntington, Sculptor THE COURIER SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES VOLUME XII, NUMBER 4 Table of Contents Fall 1975 Page The Significance of the Equestrian Monument "Joan of Arc" in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington. 3 Myrna Garvey Eden The Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington in the Syracuse University Art Collection. 13 Myrna Garvey Eden Clara E. Sipprell: American Photographer, In Memoriam 29 Ruth-Ann Appelhof News of the Library and Library Associates 33 Portrait of Anna Hyatt Huntington from Beatrice G. Proske's Archer M. Huntington, New York, Hispanic Society of America, 1963. Courtesy of Hispanic Society of America. The Significance of the Equestrian Monument "Joan of Arc" In the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington by Myrna Garvey Eden The manuscript collection of Anna Hyatt Huntington, sculptor, 1876-1973, left to the George Arents Research Library at Syracuse University by Mrs. -

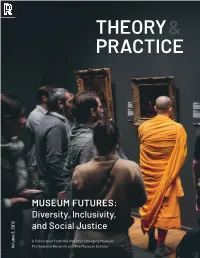

Theory Practice &

THEORY& PRACTICE MUSEUM FUTURES: Diversity, Inclusivity, and Social Justice A Publication from the National Emerging Museum Professional Network and The Museum Scholar Volume 2, 2019 Volume Curating Racism: Understanding Field Museum Physical Anthropology from 1893 to 1969 LUCIA PROCOPIO Northwestern University Theory and Practice: The Emerging Museum Professionals Journal www.TheMuseumScholar.org Rogers Publishing Corporation NFP 5558 S. Kimbark Ave, Suite 2, Chicago, IL 60637 www.rogerspublishing.org Cover photo: Antonio Molinari ©2019 The Museum Scholar The National Emerging Museum Professionals Network Theory and Practice is a peer reviewed Open Access Gold journal, permitting free online access to all articles, multi-media material, and scholarly research. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Curating Racism: Understanding Field Museum Physical Anthropology from 1893 to 1969 LUCIA PROCOPIO Northwestern University Keywords Anthropology; Scientific Racism; Field Museum Abstract Early anthropological study has often been credited with advancing both existing and new racist ideologies. As major research institutions, nineteenth and twentieth-century museums were often complicit in this process. This paper uses the Field Museum as a case study to explore how natural history museums of this period developed and propagated scientific racism. While previous research has examined the 1933 The Races of Mankind exhibition, this paper will present a broader understanding -

Spiritual Conversations with Swami Shankarananda Swami Tejasananda English Translation by Swami Satyapriyananda (Continued from the Previous Issue)

2 THE ROAD TO WISDOM Swami Vivekananda on Significance of Symbols—III n the heart of all these ritualisms, there Istands one idea prominent above all the rest—the worship of a name. Those of you who have studied the older forms of Christianity, those of you who have studied the other religions of the world, perhaps have marked that there is this idea with them all, the worship of a name. A name is said to be very sacred. In the Bible we read that the holy name of God was considered sacred beyond compare, holy consciously or unconsciously, man found beyond everything. It was the holiest of all the glory of names. names, and it was thought that this very Again, we find that in many different Word was God. This is quite true. What is religions, holy personages have been this universe but name and form? Can you worshipped. They worship Krishna, they think without words? Word and thought worship Buddha, they worship Jesus, and so are inseparable. Try if anyone of you can forth. Then, there is the worship of saints; separate them. Whenever you think, you hundreds of them have been worshipped all are doing so through word forms. The one over the world, and why not? The vibration brings the other; thought brings the word, of light is everywhere. The owl sees it in the and the word brings the thought. Thus the dark. That shows it is there, though man whole universe is, as it were, the external cannot see it. To man, that vibration is only symbol of God, and behind that stands visible in the lamp, in the sun, in the moon, His grand name. -

Berthold Laufer 1874–1934 Anthropologist, Sinologist, Curator, and Collector

Berthold Laufer 1874–1934 Anthropologist, Sinologist, Curator, and Collector Berthold Laufer, one of the most accomplished sinologists of the early twentieth century, was born in Cologne, Germany, to Max Laufer and his wife, Eugenie (neé Schlesinger). He was educated at the Friedrich Wilhelms Gymnasium in Cologne and attended Berlin University (1893–95) before he received his doctorate from the University of Leipzig in 1897. During his training he studied a range of Asian languages and cultures, from Persian and Sanskrit to Tibetan and Chinese. At the suggestion of anthropologist Franz Boas (1858–1942), Laufer accepted a position at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City in 1898, from where he joined the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1898–99) to Siberia, Alaska, and the northwest coast of Canada as an ethnographer. He led his first collecting expedition to China for the museum from 1901 to 1904. In 1908 Laufer moved to Chicago, Illinois, and worked at the Field Museum of Natural History, where he ultimately headed the Department of Anthropology. Laufer remained at the Field for the rest of his career. He led two more expeditions to China—the Blackstone Expedition of 1908–10 and the Marshall Field Expedition of 1923—and consequently formed one of the earliest comprehensive collections of Chinese material culture in the United States. During his first expedition, Laufer acquired more than 19,000 archaeological, ethnographic, and historical objects that span the period from 6000 BCE to 1890 CE. He collected an additional 1,800 objects during the 1923 expedition. Laufer also compiled extensive field reports, took photographs during these trips, and engaged in detailed correspondence with other specialists about his movements, contacts, and purchases. -

The Chronology of Swami Vivekananda in the West

HOW TO USE THE CHRONOLOGY This chronology is a day-by-day record of the life of Swami Viveka- Alphabetical (master list arranged alphabetically) nanda—his activites, as well as the people he met—from July 1893 People of Note (well-known people he came in to December 1900. To find his activities for a certain date, click on contact with) the year in the table of contents and scroll to the month and day. If People by events (arranged by the events they at- you are looking for a person that may have had an association with tended) Swami Vivekananda, section four lists all known contacts. Use the People by vocation (listed by their vocation) search function in the Edit menu to look up a place. Section V: Photographs The online version includes the following sections: Archival photographs of the places where Swami Vivekananda visited. Section l: Source Abbreviations A key to the abbreviations used in the main body of the chronology. Section V|: Bibliography A list of references used to compile this chronol- Section ll: Dates ogy. This is the body of the chronology. For each day, the following infor- mation was recorded: ABOUT THE RESEARCHERS Location (city/state/country) Lodging (where he stayed) This chronological record of Swami Vivekananda Hosts in the West was compiled and edited by Terrance Lectures/Talks/Classes Hohner and Carolyn Kenny (Amala) of the Vedan- Letters written ta Society of Portland. They worked diligently for Special events/persons many years culling the information from various Additional information sources, primarily Marie Louise Burke’s 6-volume Source reference for information set, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discov- eries. -

City of Walla Walla Arts Commission Support Services 15 N. 3Rd Avenue Walla Walla, WA 99362

City of Walla Walla Arts Commission Support Services 15 N. 3rd Avenue Walla Walla, WA 99362 CITY OF WALLA WALLA ARTS COMMISSION AGENDA Wednesday, November 4, 2020 – 10:00 AM Virtual Zoom Meting 15 N 3rd Ave 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES a. October 7, 2020 minutes 3. ACTIVE BUSINESS a. Deaccession of Public Art • Recommendation to City Council on proposed code amendments to Chapter 2.42 Recommendation to City Council regarding the Marcus Whitman Statue b. City Flag Project • Update on Status of this Project – Lindsay Tebeck Public comments will be taken on each active business item. 4. STAFF UPDATE 5. ADJOURNMENT To join Zoom Meeting: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/85918094860 Meeting ID: 859 1809 4860 One tap mobile – 1(253) 215-8782 Persons who need auxiliary aids for effective communication are encouraged to make their needs and preferences known to the City of Walla Walla Support Services Department three business days prior to the meeting date so arrangements can be made. The City of Walla Arts Commission is a seven-member advisory body that provides recommendations to the Walla Walla City Council on matters related to arts within the community. Arts Commissioners are appointed by City Council. Actions taken by the Arts Commission are not final decisions; they are in the form of recommendations to the City Council who must ultimately make the final decision. ARTS COMMISSION ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING Minutes October 7, 2020 Virtual Zoom Meeting Present: Linda Scott, Douglas Carlsen, Tia Kramer, Lindsay Tebeck, Hannah Bartman Absent: Katy Rizzuti Council Liaison: Tom Scribner Staff Liaison: Elizabeth Chamberlain, Deputy City Manager Staff support: Rikki Gwinn Call to order: The meeting was called to order at 11:02 am I. -

Taking the Skeletons out of the Closet

Taking the Skeletons Out of The Closet: Contested Authority and Human Remains Displays in the Anthropology Museum Iris Roos Jacobs A Thesis Submitted to the Departments of Anthropology and History, Philosophy, and Social Studies of Science and Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts at the University of Chicago Advisors: Dr. Michael Rossi and Dr. Maria Cecilia Lozada Preceptor: Ashley Clark Spring 2020 1 Table of Contents II. Introduction 4 a. Abstract 4 b. Methods 4 c. Overview: The Field Museum as a Reference Point in Framing Ethical Debates 8 III. Ethics in Scientific Displays of Human Remains: Transhistoric Wrongs, or Cultural Contingencies? 12 a. Modern Ethics and Ancient Traditions 12 b. Cadavers in the Science Museum 15 c. Anthropology as Natural History 16 d. Museum Anthropology and Colonialism 19 Race and the Race for Specimen Collection in the United States 20 e. Not Simply “The Scientist” versus “The Native:” Repatriation in Legal, Ethical, and Cultural Debates 22 NAGPRA at the Field 24 Divergent Views in Repatriation Debates 30 “Asking the Question”: Displaying Remains While Engaging with Ethical Debates 34 f. Beyond Repatriation: Addressing Human Remains Displays in Post-Colonial Contexts 36 IV. Museums and Spectacle: Science versus the “Edutainment Extravaganza” 41 a. Public Participation in Gilded Age Archaeology 41 b. The World’s Columbian Exhibition: The Field Museum as a “Memory of the Fair” 43 c. An Obligation to Educate: Visitor Engagement at the Field 45 d. Money, Mummies, and “Edutainment Extravaganzas” 47 e. Paleoart at the Field: Scientific Narrative, Race, and Representations of Humanity 52 f.