Museum Communication, Exhibition Policy and Plan: the Field Museum As a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Is Malvina Hofman? By: Vladimir Čeh

Vladimir Čeh (1946) Владимир Чех (1946) Институт за историју оглашавања је основан 2012. године ради The lnstitute of Advertising History was founded in 2012 to research истраживања и афирмације историје и развоја оглашавања и and raise awareness of the history and development of advertising интегрисаних маркетинг комуникација, њиховог утицаја на културу and integrated marketing communications, of their impact оn the way живљења и њихове промоције. of life and of their promotion. Philologist. After 25 years at Radio Belgrade, Реализацијом пројеката и програма који обухватају проучавање Ву implementing projects and programmes that include the study Филолог. После 25 година рада у Радио he was partner, owner and/or creative director историјских процеса, догађаја, личности и појава, Институт of historical processes, events, personalities and concepts, the Београду био партнер, власник и/или in several advertising agencies. Long-term прикупља, чува, стручно обрађује и приказује јавности lnstitute collects, preserves, expertly treats and presents to the креативни директор у неколико огласних president of the Belgrade branch of the IAA комуникацијске алате и историјску грађу од значаја за развијања public communication tools and historical material important for агенција. Дугогодишњи председник (International Advertising Association), member свести о улози и месту интегрисаних маркетинг комуникација у developing awareness of the role and place of integrated marketing Београдског огранка IAA (International of the IAA world board, president of the Serbian култури живљења. communications in society and culture. Advertising Association), члан светског борда Propaganda Association (UEPS), president of IAA, председник Удружења пропагандиста the UEPS Court of honour. Остваривањем својих циљева Институт реализује, афирмише ln pursuit of its goals, the lnstitute realizes and promotes cooperation Србије (УЕПС), председник Суда части и промовише сарадњу са музејима, архивима, библиотекама, with museums, archives, libraries, professional associations, WHO IS УЕПС-а. -

Clara E. Sipprell Papers

Clara E. Sipprell Papers An inventory of her papers at Syracuse University Finding aid created by: - Date: unknown Revision history: Jan 1984 additions, revised (ASD) 14 Oct 2006 converted to EAD (AMCon) Feb 2009 updated, reorganized (BMG) May 2009 updated 87-101 (MRC) 21 Sep 2017 updated after negative integration (SM) 9 May 2019 added unidentified and "House in Thetford, Vermont" (KD) extensively updated following NEDCC rehousing; Christensen 14 May 2021 correspondence added (MRC) Overview of the Collection Creator: Sipprell, Clara E. (Clara Estelle), 1885-1975. Title: Clara E. Sipprell Papers Dates: 1915-1970 Quantity: 93 linear ft. Abstract: Papers of the American photographer. Original photographs, arranged as character studies, landscapes, portraits, and still life studies. Correspondence (1929-1970), clippings, interviews, photographs of her. Portraits of Louis Adamic, Svetlana Allilueva, Van Wyck Brooks, Pearl S. Buck, Rudolf Bultmann, Charles E. Burchfield, Fyodor Chaliapin, Ralph Adams Cram, W.E.B. Du Bois, Albert Einstein, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Ralph E. Flanders, Michel Fokine, Robert Frost, Eva Hansl, Roy Harris, Granville Hicks, Malvina Hoffman, Langston Hughes, Robinson Jeffers, Louis Krasner, Serge Koussevitzky, Luigi Lucioni, Emil Ludwig, Edwin Markham, Isamu Noguchi, Maxfield Parrish, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dane Rudhyar, Ruth St. Denis, Otis Skinner, Ida Tarbell, Howard Thurman, Ridgely Torrence, Hendrik Van Loon, and others Language: English Repository: Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries 222 Waverly Avenue Syracuse, NY 13244-2010 http://scrc.syr.edu Biographical History Clara E. Sipprell (1885-1975) was a Canadian-American photographer known for her landscapes and portraits of famous actors, artists, writers and scientists. Sipprell was born in Ontario, Canada, a posthumous child with five brothers. -

Joan of Arc" in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Fall 1975 The Significance of the questrianE Monument "Joan of Arc" in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington Myrna Garvey Eden Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Eden, Myrna Garvey. "The Significance of the questrianE Monument 'Joan of Arc' in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington." The Courier 12.4 (1975): 3-12. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOAN OF ARC Bronze, 11.4 times life. 1915. Riverside Drive and 93rd Street, New York, New York. Anna Hyatt Huntington, Sculptor THE COURIER SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES VOLUME XII, NUMBER 4 Table of Contents Fall 1975 Page The Significance of the Equestrian Monument "Joan of Arc" in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington. 3 Myrna Garvey Eden The Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington in the Syracuse University Art Collection. 13 Myrna Garvey Eden Clara E. Sipprell: American Photographer, In Memoriam 29 Ruth-Ann Appelhof News of the Library and Library Associates 33 Portrait of Anna Hyatt Huntington from Beatrice G. Proske's Archer M. Huntington, New York, Hispanic Society of America, 1963. Courtesy of Hispanic Society of America. The Significance of the Equestrian Monument "Joan of Arc" In the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington by Myrna Garvey Eden The manuscript collection of Anna Hyatt Huntington, sculptor, 1876-1973, left to the George Arents Research Library at Syracuse University by Mrs. -

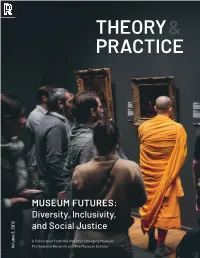

Theory Practice &

THEORY& PRACTICE MUSEUM FUTURES: Diversity, Inclusivity, and Social Justice A Publication from the National Emerging Museum Professional Network and The Museum Scholar Volume 2, 2019 Volume Curating Racism: Understanding Field Museum Physical Anthropology from 1893 to 1969 LUCIA PROCOPIO Northwestern University Theory and Practice: The Emerging Museum Professionals Journal www.TheMuseumScholar.org Rogers Publishing Corporation NFP 5558 S. Kimbark Ave, Suite 2, Chicago, IL 60637 www.rogerspublishing.org Cover photo: Antonio Molinari ©2019 The Museum Scholar The National Emerging Museum Professionals Network Theory and Practice is a peer reviewed Open Access Gold journal, permitting free online access to all articles, multi-media material, and scholarly research. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Curating Racism: Understanding Field Museum Physical Anthropology from 1893 to 1969 LUCIA PROCOPIO Northwestern University Keywords Anthropology; Scientific Racism; Field Museum Abstract Early anthropological study has often been credited with advancing both existing and new racist ideologies. As major research institutions, nineteenth and twentieth-century museums were often complicit in this process. This paper uses the Field Museum as a case study to explore how natural history museums of this period developed and propagated scientific racism. While previous research has examined the 1933 The Races of Mankind exhibition, this paper will present a broader understanding -

Spiritual Conversations with Swami Shankarananda Swami Tejasananda English Translation by Swami Satyapriyananda (Continued from the Previous Issue)

2 THE ROAD TO WISDOM Swami Vivekananda on Significance of Symbols—III n the heart of all these ritualisms, there Istands one idea prominent above all the rest—the worship of a name. Those of you who have studied the older forms of Christianity, those of you who have studied the other religions of the world, perhaps have marked that there is this idea with them all, the worship of a name. A name is said to be very sacred. In the Bible we read that the holy name of God was considered sacred beyond compare, holy consciously or unconsciously, man found beyond everything. It was the holiest of all the glory of names. names, and it was thought that this very Again, we find that in many different Word was God. This is quite true. What is religions, holy personages have been this universe but name and form? Can you worshipped. They worship Krishna, they think without words? Word and thought worship Buddha, they worship Jesus, and so are inseparable. Try if anyone of you can forth. Then, there is the worship of saints; separate them. Whenever you think, you hundreds of them have been worshipped all are doing so through word forms. The one over the world, and why not? The vibration brings the other; thought brings the word, of light is everywhere. The owl sees it in the and the word brings the thought. Thus the dark. That shows it is there, though man whole universe is, as it were, the external cannot see it. To man, that vibration is only symbol of God, and behind that stands visible in the lamp, in the sun, in the moon, His grand name. -

The Chronology of Swami Vivekananda in the West

HOW TO USE THE CHRONOLOGY This chronology is a day-by-day record of the life of Swami Viveka- Alphabetical (master list arranged alphabetically) nanda—his activites, as well as the people he met—from July 1893 People of Note (well-known people he came in to December 1900. To find his activities for a certain date, click on contact with) the year in the table of contents and scroll to the month and day. If People by events (arranged by the events they at- you are looking for a person that may have had an association with tended) Swami Vivekananda, section four lists all known contacts. Use the People by vocation (listed by their vocation) search function in the Edit menu to look up a place. Section V: Photographs The online version includes the following sections: Archival photographs of the places where Swami Vivekananda visited. Section l: Source Abbreviations A key to the abbreviations used in the main body of the chronology. Section V|: Bibliography A list of references used to compile this chronol- Section ll: Dates ogy. This is the body of the chronology. For each day, the following infor- mation was recorded: ABOUT THE RESEARCHERS Location (city/state/country) Lodging (where he stayed) This chronological record of Swami Vivekananda Hosts in the West was compiled and edited by Terrance Lectures/Talks/Classes Hohner and Carolyn Kenny (Amala) of the Vedan- Letters written ta Society of Portland. They worked diligently for Special events/persons many years culling the information from various Additional information sources, primarily Marie Louise Burke’s 6-volume Source reference for information set, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discov- eries. -

City of Walla Walla Arts Commission Support Services 15 N. 3Rd Avenue Walla Walla, WA 99362

City of Walla Walla Arts Commission Support Services 15 N. 3rd Avenue Walla Walla, WA 99362 CITY OF WALLA WALLA ARTS COMMISSION AGENDA Wednesday, November 4, 2020 – 10:00 AM Virtual Zoom Meting 15 N 3rd Ave 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES a. October 7, 2020 minutes 3. ACTIVE BUSINESS a. Deaccession of Public Art • Recommendation to City Council on proposed code amendments to Chapter 2.42 Recommendation to City Council regarding the Marcus Whitman Statue b. City Flag Project • Update on Status of this Project – Lindsay Tebeck Public comments will be taken on each active business item. 4. STAFF UPDATE 5. ADJOURNMENT To join Zoom Meeting: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/85918094860 Meeting ID: 859 1809 4860 One tap mobile – 1(253) 215-8782 Persons who need auxiliary aids for effective communication are encouraged to make their needs and preferences known to the City of Walla Walla Support Services Department three business days prior to the meeting date so arrangements can be made. The City of Walla Arts Commission is a seven-member advisory body that provides recommendations to the Walla Walla City Council on matters related to arts within the community. Arts Commissioners are appointed by City Council. Actions taken by the Arts Commission are not final decisions; they are in the form of recommendations to the City Council who must ultimately make the final decision. ARTS COMMISSION ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING Minutes October 7, 2020 Virtual Zoom Meeting Present: Linda Scott, Douglas Carlsen, Tia Kramer, Lindsay Tebeck, Hannah Bartman Absent: Katy Rizzuti Council Liaison: Tom Scribner Staff Liaison: Elizabeth Chamberlain, Deputy City Manager Staff support: Rikki Gwinn Call to order: The meeting was called to order at 11:02 am I. -

Taking the Skeletons out of the Closet

Taking the Skeletons Out of The Closet: Contested Authority and Human Remains Displays in the Anthropology Museum Iris Roos Jacobs A Thesis Submitted to the Departments of Anthropology and History, Philosophy, and Social Studies of Science and Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts at the University of Chicago Advisors: Dr. Michael Rossi and Dr. Maria Cecilia Lozada Preceptor: Ashley Clark Spring 2020 1 Table of Contents II. Introduction 4 a. Abstract 4 b. Methods 4 c. Overview: The Field Museum as a Reference Point in Framing Ethical Debates 8 III. Ethics in Scientific Displays of Human Remains: Transhistoric Wrongs, or Cultural Contingencies? 12 a. Modern Ethics and Ancient Traditions 12 b. Cadavers in the Science Museum 15 c. Anthropology as Natural History 16 d. Museum Anthropology and Colonialism 19 Race and the Race for Specimen Collection in the United States 20 e. Not Simply “The Scientist” versus “The Native:” Repatriation in Legal, Ethical, and Cultural Debates 22 NAGPRA at the Field 24 Divergent Views in Repatriation Debates 30 “Asking the Question”: Displaying Remains While Engaging with Ethical Debates 34 f. Beyond Repatriation: Addressing Human Remains Displays in Post-Colonial Contexts 36 IV. Museums and Spectacle: Science versus the “Edutainment Extravaganza” 41 a. Public Participation in Gilded Age Archaeology 41 b. The World’s Columbian Exhibition: The Field Museum as a “Memory of the Fair” 43 c. An Obligation to Educate: Visitor Engagement at the Field 45 d. Money, Mummies, and “Edutainment Extravaganzas” 47 e. Paleoart at the Field: Scientific Narrative, Race, and Representations of Humanity 52 f. -

Column of Life, 1917 Bronze, 26 1/4 In

Information on Malvina Hoffman American, 1885–1966 Column of Life, 1917 Bronze, 26 1/4 in. high Museum Purchase in memory of John Palmer Leeper with funds from Marion Harwell, by exchange, and the members of the McNay 1996.37 Subject Matter Malvina Hoffman’s Column of Life is a 26-inch vertical bronze sculpture, of warm copper colored patina. A depiction of lovers fused in an embrace, the sculpture shows a mixture of influences on the artist. The soft modeling reflects Hoffman’s study with Auguste Rodin and clearly recalls his famous sculpture The Kiss. An account of how Hoffman created this sculpture reveals his influence on her work. While waiting for Rodin in his studio, Hoffman manipulated a piece of clay into a vertical shape. When Rodin asked her about it, she replied that it was “an accident.” He commented, “There is more in this than you understand at present.” Later she transformed the accident into Column of Life, first carved in marble and then cast in bronze. In composition and compression of forms, however, Column of Life is closer to Constantin Brancusi’s Kiss of 1908. About the Artist Born in New York City, June 15, 1885, the daughter of a piano soloist with the New York Philharmonic, Malvina Hoffman grew up in a culturally prominent family, which nurtured her artistic ambitions. She attended the Women’s School of Applied Design and the Art Student’s League. Accompanied by her newly widowed mother, Malvina made her first trip to Paris in 1910. She became a favorite pupil of Rodin, and it was on his advice that she studied dissection and anatomy at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. -

Radovi Instituta Za Povijest Umjetnosti 35 UDK 7.0/77 Zagreb, 2011

Radovi Instituta za povijest umjetnosti 35 UDK 7.0/77 Zagreb, 2011. ISSN 0350-3437 Radovi Instituta za povijest umjetnosti 35 Journal of the Institute of Art History, Zagreb Rad. Inst. povij. umjet., sv. 35, Zagreb, 2011., str. 1–308 Rad. Inst. povij. umjet. 35/2011. (255–268) Dalibor Prančević: Malvina Hoffman i Ivan Meštrović: umjetnička i biografska ukrštanja dvoje kipara Dalibor Prančević Filozofski fakultet u Splitu, Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Malvina Hoffman i Ivan Meštrović: umjetnička i biografska ukrštanja dvoje kipara Prethodno priopćenje – Preliminary communication Predano 30. 6. 2011. – Prihvaćeno 15. 10. 2011. UDK: 73 Hoffman, M. 73 Meštrović, I. Sažetak Sagledavanje umjetničkih i biografskih ukrštanja američke kiparice Meštrovićeva dolaska u Ameriku u svojstvu profesora kiparstva na Malvine Hoffman i Ivana Meštrovića neobično je važno kako zbog tamošnjem Syracuse University kao i organizaciju njegove izložbe u pojašnjenja autorstva dokumentarnog filma o nastajanju Meštrovićeva Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1947. godine. Rezultat je to iskrenog spomenika Indijancima, podignutog u Chicagu 1928. godine tako i zbog prijateljstva i iznimnog poštovanja što su ih umjetnici dugo godina potpunije rekonstrukcije Meštrovićevih kretanja u ratnom vremenu i međusobno gajili. Tekst je rezultat istraživanja Arhiva Malvine Ho- vremenu poraća provedenima u Švicarskoj i Italiji. Malvina Hoffman ffman realiziranoga u Getty Research Institute u Los Angelesu, 2007. je autorica spomenutog filma no i najzaslužnija je osoba za inicijativu godine. Ključne riječi: Malvina Hoffman, Ivan Meštrović, Spomenik Indijancima, Syracuse University, William P. Tolley, manuskript o Michelangelu O Ivanu Meštroviću napisano je podosta tekstova koji se bave Američkim Državama, odnosno njenu zaslugu za kiparovo pojedinim dionicama njegova rada ili ukupnim stvaralaštvom, preseljenje na američki kontinent nakon nepovoljnih uvjeta poznanstvima što ih je ostvario sa značajnim osobama iz Drugoga svjetskog rata. -

List of Exhibitions Held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art from 1897 to 2014

National Gallery of Art, Washington February 14, 2018 Corcoran Gallery of Art Exhibition List 1897 – 2014 The National Gallery of Art assumed stewardship of a world-renowned collection of paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, prints, drawings, and photographs with the closing of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in late 2014. Many works from the Corcoran’s collection featured prominently in exhibitions held at that museum over its long history. To facilitate research on those and other objects included in Corcoran exhibitions, following is a list of all special exhibitions held at the Corcoran from 1897 until its closing in 2014. Exhibitions for which a catalog was produced are noted. Many catalogs may be found in the National Gallery of Art Library (nga.gov/research/library.html), the libraries at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/), or in the Corcoran Archives, now housed at the George Washington University (library.gwu.edu/scrc/corcoran-archives). Other materials documenting many of these exhibitions are also housed in the Corcoran Archives. Exhibition of Tapestries Belonging to Mr. Charles M. Ffoulke, of Washington, DC December 14, 1897 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. AIA Loan Exhibition April 11–28, 1898 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the Corcoran School of Art May 31–June 5, 1899 Exhibition of Paintings by the Artists of Washington, Held under the Auspices of a Committee of Ladies, of Which Mrs. John B. Henderson Was Chairman May 4–21, 1900 Annual Exhibition of the Work by the Students of the CorCoran SChool of Art May 30–June 4, 1900 Fifth Annual Exhibition of the Washington Water Color Club November 12–December 6, 1900 A catalog of the exhibition was produced. -

Charles Cordier's Ethnographic Sculptures

Re-Casting Difference: Charles Cordier’s Ethnographic Sculptures Robley Holmes A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art and Art History). Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by Daniel J. Sherman Carol Magee Lyneise Williams ©2011 Robley Holmes ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Robley Holmes Re-Casting Difference: Charles Cordier’s Ethnographic Sculptures (Under the direction of Daniel J. Sherman) Examining Cordier’s nineteenth-century ethnographic busts, I argue that their contemporary exhibition must include the contexts of their creation and early display. Curators in the twenty-first century approach his works as celebrations of visual difference motivated by curiosity and artistic search for beauty. Yet Cordier showed these works in different types of venues, considering the sculptures both artistic and scientific. He worked from live models, traveling to Algeria to make busts of different racial types. Given these issues, discourses of Orientalism, anthropological racial theories, and colonial movement frame my analysis of his choice of non-French subjects, his sculptural process, and his use of multimedia and polychromy. I analyze these works looking at both historical and contemporary displays and aspects of Cordier’s biography, as well as journals and travel guides. iii Acknowledgments I am extremely grateful to Professor Daniel J. Sherman for his guidance throughout this process, and for his clear, intelligent, and thorough critique of my many drafts. I would like to thank Professor Carol Magee for her generosity, patience, and rigor, as well as Professor Lyneise Williams for her help and enthusiasm.