Joan of Arc" in the Artistic Development of Anna Hyatt Huntington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Is Malvina Hofman? By: Vladimir Čeh

Vladimir Čeh (1946) Владимир Чех (1946) Институт за историју оглашавања је основан 2012. године ради The lnstitute of Advertising History was founded in 2012 to research истраживања и афирмације историје и развоја оглашавања и and raise awareness of the history and development of advertising интегрисаних маркетинг комуникација, њиховог утицаја на културу and integrated marketing communications, of their impact оn the way живљења и њихове промоције. of life and of their promotion. Philologist. After 25 years at Radio Belgrade, Реализацијом пројеката и програма који обухватају проучавање Ву implementing projects and programmes that include the study Филолог. После 25 година рада у Радио he was partner, owner and/or creative director историјских процеса, догађаја, личности и појава, Институт of historical processes, events, personalities and concepts, the Београду био партнер, власник и/или in several advertising agencies. Long-term прикупља, чува, стручно обрађује и приказује јавности lnstitute collects, preserves, expertly treats and presents to the креативни директор у неколико огласних president of the Belgrade branch of the IAA комуникацијске алате и историјску грађу од значаја за развијања public communication tools and historical material important for агенција. Дугогодишњи председник (International Advertising Association), member свести о улози и месту интегрисаних маркетинг комуникација у developing awareness of the role and place of integrated marketing Београдског огранка IAA (International of the IAA world board, president of the Serbian култури живљења. communications in society and culture. Advertising Association), члан светског борда Propaganda Association (UEPS), president of IAA, председник Удружења пропагандиста the UEPS Court of honour. Остваривањем својих циљева Институт реализује, афирмише ln pursuit of its goals, the lnstitute realizes and promotes cooperation Србије (УЕПС), председник Суда части и промовише сарадњу са музејима, архивима, библиотекама, with museums, archives, libraries, professional associations, WHO IS УЕПС-а. -

Clara E. Sipprell Papers

Clara E. Sipprell Papers An inventory of her papers at Syracuse University Finding aid created by: - Date: unknown Revision history: Jan 1984 additions, revised (ASD) 14 Oct 2006 converted to EAD (AMCon) Feb 2009 updated, reorganized (BMG) May 2009 updated 87-101 (MRC) 21 Sep 2017 updated after negative integration (SM) 9 May 2019 added unidentified and "House in Thetford, Vermont" (KD) extensively updated following NEDCC rehousing; Christensen 14 May 2021 correspondence added (MRC) Overview of the Collection Creator: Sipprell, Clara E. (Clara Estelle), 1885-1975. Title: Clara E. Sipprell Papers Dates: 1915-1970 Quantity: 93 linear ft. Abstract: Papers of the American photographer. Original photographs, arranged as character studies, landscapes, portraits, and still life studies. Correspondence (1929-1970), clippings, interviews, photographs of her. Portraits of Louis Adamic, Svetlana Allilueva, Van Wyck Brooks, Pearl S. Buck, Rudolf Bultmann, Charles E. Burchfield, Fyodor Chaliapin, Ralph Adams Cram, W.E.B. Du Bois, Albert Einstein, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Ralph E. Flanders, Michel Fokine, Robert Frost, Eva Hansl, Roy Harris, Granville Hicks, Malvina Hoffman, Langston Hughes, Robinson Jeffers, Louis Krasner, Serge Koussevitzky, Luigi Lucioni, Emil Ludwig, Edwin Markham, Isamu Noguchi, Maxfield Parrish, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dane Rudhyar, Ruth St. Denis, Otis Skinner, Ida Tarbell, Howard Thurman, Ridgely Torrence, Hendrik Van Loon, and others Language: English Repository: Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries 222 Waverly Avenue Syracuse, NY 13244-2010 http://scrc.syr.edu Biographical History Clara E. Sipprell (1885-1975) was a Canadian-American photographer known for her landscapes and portraits of famous actors, artists, writers and scientists. Sipprell was born in Ontario, Canada, a posthumous child with five brothers. -

Direct PDF Link for Archiving

Andrew Eschelbacher book review of Les Bronzes Bardedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs by Florence Rionnet Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Citation: Andrew Eschelbacher, book review of “Les Bronzes Bardedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs by Florence Rionnet,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2017.16.2.6. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Eschelbacher: Les Bronzes Bardedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs by Florence Rionnet Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Florence Rionnet, Les bronzes Barbedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs. Paris: Arthena, 2016. 571 pp.; 1300 illus. (200 color and 1100 b&w illus.); bibliography; index. €140 ISBN: 978-2-903239-58-9 Florence Rionnet’s monumental study on the history of the Barbedienne foundry and the bronze sculptures it created between 1834 and 1954 is a timely and vast reference tome. Lushly illustrated and rich with archival research, Les bronzes Barbedienne sheds substantial new light on the operations of one of France’s most significant foundries in an age when sculptural production increased through its intersection with industrial processes. The Maison Barbedienne was at the center of this phenomenon and Rionnet’s book, which includes a catalogue of over 2000 objects, proves expansive in its history of the foundry and in its connections to broader trends of French artistic society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. -

Current Affairs

CUBA Current Affairs Year I / No.3 Embassy of Cuba in Cambodia CONTENT Cuba is a safe, peaceful and healthy country FBI: No evidence of “sonic attacks” in Cuba ………….2 In the morning of January 9, a hearing was held in the Over a million U.S. citizens Senate Foreign Relations visited Cuba in 2017 …..... 3 Subcommittee on Western Intl. Tourism Fair recognizes Hemisphere, organized by Cuba as safe country ...….. 3 Republican Senator for Flori- A realistic perspective on da Marco Rubio and co- Cuba´s economy …….….. 4 chaired by New Jersey De- Significant Cuba´s 2017 mocrat Senator Robert Me- economy figures ………… 5 nendez, both with a vast re- A labor of love: Anna cord of work against better Hyatt’s equestrian statue of relations between Cuba and the United States, and the Martí …………………... 6 promoters of all kinds of le- Martí’s legacy to be remem- Author: Josefina Vidal | [email protected] gislative and political propo- bered throughout January ..7 sals that affect the interests of Cuba has a lung cáncer vac- the Cuban and American peoples, and only benefit an increasingly isolated minority cine ……………………… 8 that has historically profited from attacks on Cuba. Working to save lives from From its very title “Attacks on U.S. Diplomats in Cuba,” it was evident that the true the very beginning ……. 10 purpose of this hearing, to which three high-ranking officials of the State Department Casa de las Américas in were summoned, was not to establish the truth, but to impose by force and without any evidence an accusation that they have not been able to prove. -

'A Baby's Unconsciousness' in Sculpture: Modernism, Nationalism

Emily C. Burns ‘A baby’s unconsciousness’ in sculpture: modernism, nationalism, Frederick MacMonnies and George Grey Barnard in fin-de-siècle Paris In 1900 the French critic André Michel declared the US sculpture on view at the Exposition Universelle in Paris as ‘the affirmation of an American school of sculpture’.1 While the sculptors had largely ‘studied here and … remained faithful to our salons’, Michel concluded, ‘the influence of their social and ethnic milieu is already felt in a persuasive way among the best of them’.2 How did Michel come to declare this uniquely American school? What were the terms around which national temperament – what Michel describes as a ‘social and ethnic milieu’ – was seen as manifest in art? Artistic migration to Paris played a central role in the development of sculpture in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hundreds of US sculptors trained in drawing and modelling the human figure at the Ecole des beaux-arts and other Parisian ateliers.3 The circulation of people and objects incited a widening dialogue about artistic practice. During the emergence of modernism, debates arose about the relationships between tradition and innovation.4 Artists were encouraged to adopt conventions from academic practice, and subsequently seek an individuated intervention that built on and extended that art history. Discussions about emulation and invention were buttressed by political debates about cultural nationalism that constructed unique national schools.5 In 1891, for example, a critic bemoaned that US artists were imitative in their ‘thoughtless acceptance of whatever comes from Paris’.6 By this period, US artists were coming under fire for so fully adopting French academic approaches that their art seemed inextricably tied to its foreign model. -

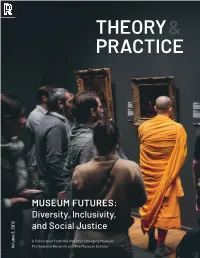

Theory Practice &

THEORY& PRACTICE MUSEUM FUTURES: Diversity, Inclusivity, and Social Justice A Publication from the National Emerging Museum Professional Network and The Museum Scholar Volume 2, 2019 Volume Curating Racism: Understanding Field Museum Physical Anthropology from 1893 to 1969 LUCIA PROCOPIO Northwestern University Theory and Practice: The Emerging Museum Professionals Journal www.TheMuseumScholar.org Rogers Publishing Corporation NFP 5558 S. Kimbark Ave, Suite 2, Chicago, IL 60637 www.rogerspublishing.org Cover photo: Antonio Molinari ©2019 The Museum Scholar The National Emerging Museum Professionals Network Theory and Practice is a peer reviewed Open Access Gold journal, permitting free online access to all articles, multi-media material, and scholarly research. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Curating Racism: Understanding Field Museum Physical Anthropology from 1893 to 1969 LUCIA PROCOPIO Northwestern University Keywords Anthropology; Scientific Racism; Field Museum Abstract Early anthropological study has often been credited with advancing both existing and new racist ideologies. As major research institutions, nineteenth and twentieth-century museums were often complicit in this process. This paper uses the Field Museum as a case study to explore how natural history museums of this period developed and propagated scientific racism. While previous research has examined the 1933 The Races of Mankind exhibition, this paper will present a broader understanding -

A Finding Aid to the George Grey Barnard Papers, Circa 1860-1969, Bulk 1880-1938, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the George Grey Barnard Papers, circa 1860-1969, bulk 1880-1938, in the Archives of American Art Kathleen Brown Funding for the processing and digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Glass plate negatives in this collection were digitized in 2019 with funding provided by the Smithsonian Women's Committee. August 03, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1888-1955..................................................... 4 Series 2: Correspondence, -

2012 Sculpture

NINETEENTH & EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY EUROPEAN SCULPTURE MAY 3rd – JULY 6th, 2012 SHEPHERD & DEROM GALLERIES © Copyright: Robert J. F. Kashey and David Wojciechowski for Shepherd Gallery, Associates, 2012 TECHNICAL NOTE: All measurements are approximate and in inches and centimeters. Prices on request. All works subject to prior sale. CATALOG ENTRIES by Jennifer S. Brown, Elisabeth Kashey, and Leanne M. Zalewski. NINETEENTH & EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY EUROPEAN SCULPTURE May 3rd through July 6th, 2012 Exhibition organized by Robert Kashey and David Wojciechowski Catalog compiled and edited by Jennifer Spears Brown SHEPHERD & DEROM GALLERIES 58 East 79th Street New York, N.Y. 10075 Tel: 212 861 4050 Fax: 212 772 1314 [email protected] www.shepherdgallery.com NINETEENTH & EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY EUROPEAN SCULPTURE May 3rd through July 6th, 2012 Shepherd Gallery presents an exhibition of Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century European Sculpture, which has been organized in conjunction with our new publication, Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century European Sculpture: A Handbook. The exhibition corresponds to the handbook’s exploration of the materials, casting techniques, founders and editors involved in the making of sculpture in Europe from 1800 to 1920. On display are reductions and enlargements of individual models; plaster casts produced for special purposes; sculptures in a variety of media; and works that exemplify the aesthetic differences in chasing and modeling techniques from 1800 to 1920. Together, the handbook and the exhibition help the viewers to identify the complexities involved in the appreciation of sculpture from this period. CATALOG ALEXY, Károly 1823-1880 Hungarian School PRINCE EUGENE OF SAVOY, 1844 Bronze on square base. -

Spiritual Conversations with Swami Shankarananda Swami Tejasananda English Translation by Swami Satyapriyananda (Continued from the Previous Issue)

2 THE ROAD TO WISDOM Swami Vivekananda on Significance of Symbols—III n the heart of all these ritualisms, there Istands one idea prominent above all the rest—the worship of a name. Those of you who have studied the older forms of Christianity, those of you who have studied the other religions of the world, perhaps have marked that there is this idea with them all, the worship of a name. A name is said to be very sacred. In the Bible we read that the holy name of God was considered sacred beyond compare, holy consciously or unconsciously, man found beyond everything. It was the holiest of all the glory of names. names, and it was thought that this very Again, we find that in many different Word was God. This is quite true. What is religions, holy personages have been this universe but name and form? Can you worshipped. They worship Krishna, they think without words? Word and thought worship Buddha, they worship Jesus, and so are inseparable. Try if anyone of you can forth. Then, there is the worship of saints; separate them. Whenever you think, you hundreds of them have been worshipped all are doing so through word forms. The one over the world, and why not? The vibration brings the other; thought brings the word, of light is everywhere. The owl sees it in the and the word brings the thought. Thus the dark. That shows it is there, though man whole universe is, as it were, the external cannot see it. To man, that vibration is only symbol of God, and behind that stands visible in the lamp, in the sun, in the moon, His grand name. -

Anna H Yatt Huntington

Anna Hyatt Huntington Anna Hyatt De la Hispanic Society al Museo Nacional de Cerámica De la Hispanic Society al Museu Nacional de Ceràmica From the Hispanic Society to the National Museum of Ceramics Anna Hyatt Huntington Anna Hyatt Anna Vaughn Hyatt nació el 10 de marzo de 1876 en Cambridge, Massachussets. Su padre fue el zoólogo y paleontólogo Alpheus Hyatt, profesor en la Universidad de Harvard y el MIT. Anna Hyatt estudió en el Art Students League de Nueva York y en la Escuela de Bellas Artes de la Universidad de Syracuse y se formó con varios escultores, entre los cuales Gutzon Borglum. Influida por la actividad de su padre, su interés por la fauna se manifestó tempranamente. Empezó a exponer su obra en 1898 y en 1906 ya había alcanzado una reputación como escultora animalística. Vivió en Europa de 1906 a 1908 y en 1910 obtuvo una mención de honor en el Salón de París con la estatua ecuestre de Juana de Arco, que se erigió en Riverside Drive, Nueva York, en 1915. Las estatuas ecuestres heroicas constituyen de hecho una parte impor- tante y reconocida en su trayectoria artística. En 1923 contrajo matrimonio con Archer Milton Huntington, fundador de la Hispanic Society of America, quien le transmitió su amor por la lengua y la cultura españolas. De 1927 a 1944 decoró los patios de la Hispanic Society con varias obras monumentales, entre las que destaca la estatua ecuestre del Cid que se ha convertido en un símbolo de la institución. En 1930 creó, junto a su marido, los Brookgreen Gardens, un gran museo de escultura al aire libre y en 1932, el Mariner’s Museum en Newport News, Virginia. -

Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2015 The Artist, the Workhorse: Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington Brooke Baerman Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Sculpture Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Baerman, Brooke, "The Artist, the Workhorse: Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington" (2015). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 818. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/818 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Artist, the Workhorse: Labor in the Sculpture of Anna Hyatt Huntington A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Brooke Baerman Candidate for a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Renée Crown University Honors May 2015 Honors Capstone Project in Art History Capstone Project Advisor: _______________________ Sascha Scott, Professor of Art History Capstone Project Reader: _______________________ Romita Ray, Professor of Art History Honors Director: _______________________ Stephen Kuusisto, Director Date: April 22, 2015 1 Abstract Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876-1973) was an American sculptor of animals who founded the nation’s first sculpture garden, Brookgreen Gardens, in 1932. -

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens Page #1 *********** (Rev

USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens Page #1 *********** (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens other name/site number: 2. Location street & number: U.S. Highway 17 not for publication: N/A city/town: Murrells Inlet vicinity: X state: SC county: Georgetown code: 043 zip code: 29576 3. Classification Ownership of Property: private Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing _10_ buildings _1_ sites _5_ structures _0_ objects 16 Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 9 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Atalaya and Brookgreen Gardens Page #2 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ req'uest for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. __ See continuation sheet. Signature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. __ See continuation sheet. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 5. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register __ See continuation sheet.