Sculpture and Modernity in Europe, 1865-1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection Paul Cézanne Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1904–06 (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire) oil on canvas Collection of the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE WINTER 2015 Contents Program Information and Goals .................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition Cézanne and the Modern ........................................................................... 4 Preparing Your Students: Nudes in Art ....................................................................................................... 5 Artists’ Background ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Modern European Art Movements .............................................................................................................. 8 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. About the Artists ....................................................................................................................... 9 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 10 Modern European Art Movements Fact Sheet .................................................................... 12 Student Worksheet ............................................................................................................... -

COLOR in the CONSTRUCTED RELIEF a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment Of

COLOR IN THE CONSTRUCTED RELIEF A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art College of Arts and Science University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan by David Stewart Geary Saskatoon, Saskatchewan 0 1985 D.S.Geary The author has agreed that the Library, University of Saskatchewan, may make this thesis freely available for inspection. Moreover, the author has agreed that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who super- vised the thesis work recorded herein or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which the thesis work was done. It is understood that due recognition will be given to the University of Saskatchewan in any use of the material in this thesis. Copying or publi- cation or any other use of the thesis for financial gain, without the approval of the University of Saskatchewan and the author's written permission, is prohibited. Requests for permission to copy or to make any other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Art University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Canada. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation and thanks to Professor Eli Bornstein for his invaluable help and support in the form of advice, assistance and example during the course of my graduate studies and before. Also I wish to thank the College of Graduate Studies and Research who provided me with much needed financial assistance in the form of scholarships. -

Having Had the Opportunity This Summer, During a Short Stay In. Sweden and Denmark, of Being Present at the International Congre

II. E INTERNATIONANOTICTH F O E L CONGRES F PREHISTORIO S C ARCHAEOLOGY HELD AT STOCKHOLM IN AUGUST 1874. BY B. W. COCHRAN PATRICK, ESQ., B.A., LL.B., P.S.A. SCOT. opportunite Havinth d gha y this summer, durin gshora t stay in. Sweden and Denmark, of being present at the International Congress of Archaeo- logists at Stockholm, in August, possibly the following brief notice of it, written at the time, may he of interest to some of the members of the Society. The meetin lase th te sevent f seasogth o s hnwa whic s beehha n held. The object of the Congress is to bring together archaeologists from every worlde parth f discuso to t , s subject antiquariaf so n interest connected with prehistoric man. Paper e member th reae e Congres y ar th sb d f o s s on these subjectsgeneralle ar d an ,arrangeo ys d that they have referenco et countre th timee whichn yi meetinth e r th , fo , g takes place. By a standing rule all the papers are written, and public discussion 1 Scotchron. lib. xiii. cap. 42, vol. ii. p. 327. ON THE INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS HELD AT STOCKHOLM. 103 take's place in French. It has been arranged that the next meeting shall take place at Buda-Pesth. In. many respects the meeting of last year has been the most successful which has been held, and besides nearly a thousand Swedes and Norwe- gians, about four hundred foreign members were present. The Congress was opened on the 7th of August. -

February, 1955

Library of The Harvard Musical Association Bulletin No. 23 February, 1955 Library Committee CHARLES R. NUTTER JOHN N. BURK RICHARD G. APPEL CYRUS DURGIN RUDOLPH ELIE Director of the Library and Library and Custodian of the Marsh Room Marsh Room Marsh Room CHARLES R. NUTTER MURIEL FRENCH FLORENCE C. ALLEN To the Members of the Association: Your attention is called to an article in this issue by Albert C. Koch. * * * * REPORT ON THE LIBRARY AND ON THE MARSH ROOM FOR THE YEAR 1954 To the President and the Directors of The Harvard Musical Association: Today, when television and the radio, both A.M. and F.M., are providing much of the intellectual sustenance for the common man and woman, the individual who turns for an intellectual repast to the writers of past centuries and also tries to phrase his thoughts both vocal and written with some regard to the rules of grammar and the principles of rhetoric is regarded as high‐brow and is thrown out of society. I am aware that I lay myself open to the charge of being a high‐brow, a charge that creates no reactionary emotion at all, especially as it comes usually from the low‐brow, and that I may be thrown out of society into a lower stratum, when I state that for the text of this report I have turned to a gentleman whose mortal life spanned the years between 1672 and 1719. Even the low‐brow has probably heard or read the name Joseph Addison, though it may convey nothing to him except the fact that it has an English and not a foreign sound. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Casting Rodin’s Thinker Sand mould casting, the case of the Laren Thinker and conservation treatment innovation Beentjes, T.P.C. Publication date 2019 Document Version Other version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Beentjes, T. P. C. (2019). Casting Rodin’s Thinker: Sand mould casting, the case of the Laren Thinker and conservation treatment innovation. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 Chapter 2 The casting of sculpture in the nineteenth century 2.1 Introduction The previous chapter has covered the major technical developments in sand mould casting up till the end of the eighteenth century. These innovations made it possible to mould and cast increasingly complex models in sand moulds with undercut parts, thus paving the way for the founding of intricately shaped sculpture in metal. -

Craft Production: Ceramics, Textiles, and Bone

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 06/04/2013, SPi c h a p t e r 2 6 craft production: ceramics, textiles, and bone j o a n n a s o f a e r , l i s e b e n d e r j ø r g e n s e n , a n d a l i c e c h o y k e I n t r o d u c t i o n Th e Bronze Age witnessed an unprecedented fl owering of craft activity. Th roughout the period there were developments in decorative motifs, techniques, and skill with distinctive emphasis on the pleasing aesthetic through intricately elaborated objects made of a wide range of contrasting materials. Th ese include metal, clay, bone, textiles, wood, bark, horn, antler, ivory, hide, amber, jet, stone, fl int, reeds, shell, glass, and faience, either alone or in combination. Yet this period precedes the development of the state and urbanism, in which the creation of art became recognized as a distinct activity. Although the Bronze Age was a period of common cultural values across Europe, craft s were performed in regionally specifi c ways leading to diversity of practice. Local develop- ments in metalworking are well understood, but a frequent emphasis on metalworking has oft en been to the detriment of other craft s, some of which played a major role in everyday life. Th is chapter examines craft production in three contrasting materials that would have been widespread in the Bronze Age: ceramics, textiles, and bone. -

Direct PDF Link for Archiving

Andrew Eschelbacher book review of Les Bronzes Bardedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs by Florence Rionnet Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Citation: Andrew Eschelbacher, book review of “Les Bronzes Bardedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs by Florence Rionnet,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2017.16.2.6. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Eschelbacher: Les Bronzes Bardedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs by Florence Rionnet Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 2 (Autumn 2017) Florence Rionnet, Les bronzes Barbedienne: l’oeuvre d’une dynastie de fondeurs. Paris: Arthena, 2016. 571 pp.; 1300 illus. (200 color and 1100 b&w illus.); bibliography; index. €140 ISBN: 978-2-903239-58-9 Florence Rionnet’s monumental study on the history of the Barbedienne foundry and the bronze sculptures it created between 1834 and 1954 is a timely and vast reference tome. Lushly illustrated and rich with archival research, Les bronzes Barbedienne sheds substantial new light on the operations of one of France’s most significant foundries in an age when sculptural production increased through its intersection with industrial processes. The Maison Barbedienne was at the center of this phenomenon and Rionnet’s book, which includes a catalogue of over 2000 objects, proves expansive in its history of the foundry and in its connections to broader trends of French artistic society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. -

Conference New Sculptors, Old Masters: the Victorian Renaissance of Italian Sculpture Friday 9 March 2019, 10.00–17.30 Henry Moore Lecture Theatre, Leeds Art Gallery

Conference New Sculptors, Old Masters: The Victorian Renaissance of Italian Sculpture Friday 9 March 2019, 10.00–17.30 Henry Moore Lecture Theatre, Leeds Art Gallery Programme 10.00–10.15 Welcome and Opening Remarks Dr Charlotte Drew (University of Bristol) 10.15–12.15 Site and Seeing: Encountering Italian Sculpture in the Nineteenth Century Chair: Dr Charlotte Drew (University of Bristol) 10.15–10.35 Prof. Martha Dunkelmann (Canisius College, Buffalo) ‘Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Donatello’ 10.35–10.55 Thomas Couldridge (Durham University) ‘South Kensington’s Cupid and Modern Receptions: A New Chapter’ 10.55–11.15 Discussion Chair: Dr Melissa Gustin (Henry Moore Institute) 11.15–11.35 Dr Deborah Stein (Boston College) ‘Charles Callahan Perkins’ Outline Illustrations of his Art Historical Scholarship on Early Italian Renaissance Sculpture’ 11.35–11.55 Dr Lynn Catterson (Columbia University, New York) ‘New Sculptors, New Old Masters: The Manufacture of Italian Renaissance Art in the Late Nineteenth-century Art Market’ 11.55–12.15 Discussion 12.15–13.30 Lunch 13.30–15.00 Italian Sculpture and the Decorative Chair: TBC 13.30–13.50 Dr Juliet Carroll (Liverpool John Moores University) ‘Encountering the Unique: The Della Robbia Pottery of Birkenhead and the Architectural Bas-reliefs of Luca della Robbia’ 13.50–14.10 Samantha Scott (University of York) ‘Lithophanes and the Italian Renaissance: Translation between Two and Three Dimensions’ 14.10–14.30 Dr Ciarán Rua O’Neill (University of York) ‘More Versatile than Most: Alfred Gilbert and Benvenuto Cellini’ 14.30–15.00 Discussion 15.00–15.30 Tea Break 15.30–17.00 Old Masters, New Mistresses Chair: Prof. -

Abbot Suger's Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis

DE CONSECRATIONIBUS: ABBOT SUGER’S CONSECRATIONS OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. DENIS by Elizabeth R. Drennon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth R. Drennon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Elizabeth R. Drennon Thesis Title: De Consecrationibus: Abbot Suger’s Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis Date of Final Oral Examination: 15 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Elizabeth R. Drennon, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Erik J. Hadley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Lisa McClain, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION I dedicate this to my family, who believed I could do this and who tolerated my child-like enthusiasm, strange mumblings in Latin, and sudden outbursts of enlightenment throughout this process. Your faith in me and your support, both financially and emotionally, made this possible. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lisa McClain for her support, patience, editing advice, and guidance throughout this process. I simply could not have found a better mentor. -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher. -

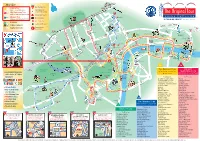

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk