Emotion, Femininity and Everyday Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trixie Mattel and Katya Dating

UNHhhh ep 5: "Dating PART 2" with Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 4: "Dating" with Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 3: "Traveling" w/ Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. UNHhhh ep 2: "RDR8 Cast Advice" w/ Trixie Mattel & Katya Zamolodchikova. 1 day ago · Trixie and Katya are back with new episodes of UNHhhh Season 5 and they've got the trailer to prove it. Here's everything you need to know about Trixie and Katya. Trixie Mattel is the stage name of Brian Firkus, a drag queen, performer, comedian and music artist best known as a Season 7 contestant of RuPaul's Drag Race and the winner of All Stars Following the success she got thanks to the show, Trixie started presenting a web show with Katya, entitled "UNHhhh", on the WOWPresents' YouTube renuzap.podarokideal.ru later starred on their new show entitled . Jul 15, · Katya: Paint on a different one! Trixie Mattel: This is a window for you, Carolyn, to become the new hot girl in the office right under everyone’s noses. Because you watched a few makeup. Mar 27, · Ever since Katya Zamolodchikova returned to Twitter, fans have been anxiously awaiting to see if the drag star would say anything about her friend and former co-star Trixie Mattel’s win on. Mar 24, · — Trixie Mattel (@trixiemattel) December 20, Trixie hasn’t revealed much about her boyfriend. She protects him from social media users as well. Trixie Mattel Net Worth and TV shows. The drag queen, Trixie Mattel has an estimated net worth of $2 million. Trixie started performing drag in the year at LaCage NiteClub. -

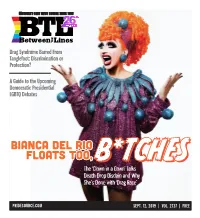

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

Fatima Mechtab, There Is Only One Remedy: More Mocktails!

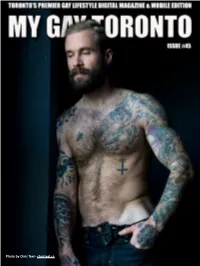

MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Photo by Chris Teel - christeel.ca My Gay Toronto page: 1 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 2 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 3 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 4 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Alaska Thunderfuck and Bianca Del Rio werq the queens who Werq the World RAYMOND HELKIO Queens Werq the World is coming to the Danforth Music Hall on Friday May 26, 2017. Get your tickets early because a show this epic only comes around once in a while. Alaska Thunderfuck, Alys- sa Edwards, Detox, Latrice Royale and Shangela, plus from season nine of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Aja, Peppermint, Sasha Velour and Trinity Taylor. Shangela recently told Gay Times Magazine “This is the most outrageous and talented collection of queens that have ever toured together. We’re calling this the Werq the World tour because that’s exactly what these Drag Race stars will be doing for fans: Werqing like they’ve never Werqued it before!” I caught up with Alaska and Bianca to get the dish on the upcoming show and the state of drag. My Gay Toronto page: 5 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 What is the most loving thing you’ve ever seen another contestant on RDR do? Alaska: Well I do have to say, when I saw Bianca hand over her extra waist cincher to Adore, I was very mesmerized by the compassion of one queen helping out another, and Drag Race is such a competitive competition and you always want the upper hand, I think that was so mething so genuine and special. -

“Rupaul's Drag Race” Season Nine Premiere!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: SOUTH FLORIDA’S VERY OWN THE GRAND RESORT AND SPA IS A NEW PROUD SPONSOR OF VH1’S “RUPAUL'S DRAG RACE” SEASON NINE PREMIERE! FORT LAUDERDALE, FL – Saturday, March 25, 2017: RuPaul’s Drag Race kicked off their season nine premiere on VH1 on Friday, March 24th at 8:00 pm EST. During its first episode, Emmy Awarder Winner, RuPaul awarded contestant, Nina Bo’nina Brown, a trip to Fort Lauderdale Beach’s, The Grand Resort and Spa. The prize included a one week stay, for two, in the 2 bedroom, 2 bathroom Grand Penthouse that boasts an 800 square foot private, ocean view terrace with a Jacuzzi and outdoor shower. Also included in this prize package will be airfare for two, and a complimentary massage and facial. The total prize value of $6,000. Casey Koslowski, Proprietor of The Grand, states that he looks forward to seeing Nina and his guest, at his award- winning spa-resort and sunning themselves on Fort Lauderdale Beach very soon! The Grand Resort and Spa is Fort Lauderdale’s premiere gay-owned and operated men’s spa- resort that first opened in 1999. With 33 well-appointed rooms and suites, it is located just steps from the beach and convenient to all of Fort Lauderdale’s attractions and nightlife. As Fort Lauderdale’s first gay resort with its own full-service day spa and hair studio, they offer guests an experience that is unique and wonderfully indulgent. From a relaxing Swedish massage to a haircut before your night on the town, the talented staff can accommodate all your needs – guaranteed to “Exceed Expectations.” A sample of the property’s awards and accolades include “Certificate of Excellence, Hall of Fame” – TripAdvisor; “Editor’s Choice” – Man About World; “#1 in Fort Lauderdale” – Pink Choice Award; "Best Small Hotel or Resort in the World" - Out Traveler Award Winner; "Top 10 Resorts" - The Travel Channel; "One of the top 10 gay-owned spas in the United States" – Out Traveler Magazine; “USA TODAY 10 BEST” – USA TODAY. -

Bob the Drag Queen and Peppermint's Star Studded “Black Queer Town Hall”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOB THE DRAG QUEEN AND PEPPERMINT’S STAR STUDDED “BLACK QUEER TOWN HALL” IS A REMINDER: BLACK QUEER PEOPLE GAVE US PRIDE Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Tiq Milan, Shea Diamond, Alex Newell, and Basit Among Participants NYC Pride and GLAAD to Support Three Day Virtual Event to Raise Funds for Black Queer Organizations and NYC LGBTQ Performers on June 19, 20, 21 New York, NY, Friday, June 12, 2020 – Advocates and entertainers Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen, today announced the “Black Queer Town Hall,” one of NYC Pride’s official partner events this year. NYC Pride and GLAAD, the global LGBTQ media advocacy organization, will stream the virtual event on YouTube and Facebook pages each day from 6:30-8pm EST beginning on Friday, June 19 and through Sunday, June 21, 2020. Performers and advocates slated to appear include Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Shea Diamond, Tiq Milan, Alex Newell, and Basit. Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen will host and produce the event. For a video featuring Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen and more information visit: https://www.gofundme.com/f/blackqueertownhall The “Black Queer Town Hall” will feature performances, roundtable discussions, and fundraising opportunities for #BlackLivesMatter, Black LGBTQ organizations, and local Black LGBTQ drag performers. The new event replaces the previously announced “Pride 2020 Drag Fest” and will shift focus of the event to center Black queer voices. During the “Black Queer Town Hall,” a diverse collection of LGBTQ voices will celebrate Black LGBTQ people and discuss pathways to dismantle racism and white supremacy. -

Kimmel Center Cultural Campus Presents Critically-Acclaimed Drag Theatre Show Spectacular Sasha Velour's Smoke & Mirrors

Tweet It! Drag icon @Sasha_Velour’s revolutionary show “Smoke & Mirrors” will be at the @KimmelCenter on 11/12. The effortless blend of drag, visual art, and magic is a can’t-miss! More info @ kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Lauren Woodard Jessica Christopher 215-790-5835 267-765-3738 [email protected] [email protected] KIMMEL CENTER CULTURAL CAMPUS PRESENTS CRITICALLY-ACCLAIMED DRAG THEATRE SHOW SPECTACULAR SASHA VELOUR’S SMOKE & MIRRORS, COMING TO THE MERRIAM THEATER NOVEMBER 12, 2019 "Smoke & Mirrors is a spellbinding tour de force." - Forbes “The intensely personal [Smoke & Mirrors] shows what a top-of-her-game queen Velour really is, both as an artist and as a storyteller.” - Paper Magazine "[Velour’s] most spectacular stage gambit yet." - Time Out New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, October 9, 2019) – Sasha Velour’s Smoke & Mirrors, the critically-acclaimed one-queen show by global drag superstar and theatre producer, Sasha Velour, will come to the Kimmel Center Cultural Campus’ Merriam Theater on November 12, 2019 at 8:00 p.m., as part of the show’s 23-city North American tour. This is Velour’s first solo tour, following her win of RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 9, and sold-out engagements of Smoke & Mirrors in New York City, Los Angeles, London, Australia, and New Zealand this year. “Sasha Velour is a drag superstar, as well as an astonishing talent in the visual arts,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Smoke & Mirrors invites audiences to experience the depths of Velour that have yet to be explored in the public eye. -

Christian Ulvert, the Man Behind the Candidates

Christian Ulvert (left), LOCAL NAME pictured next to his husband. GLOBAL COVERAGE Photo via Facebook. DECEMBER 23, 2020 VOL. 11 // ISSUE 51 PAGE 4 POWERBROKER CHRISTIAN ULVERT, THE MAN BEHIND THE CANDIDATES SOUTHFLORIDAGAYNEWS @SFGN SFGN.COM NEWS HIGHLIGHT SouthFloridaGayNews.com @SFGN December 23, 2020 • Volume 11 • Issue 51 2520 N. Dixie Highway • Wilton Manors, FL 33305 SKI CHAMPION COMES OUT AS GAY Phone: 954-530-4970 Fax: 954-530-7943 Publisher • Norm Kent [email protected] ‘IT’S A PART OF ME AND I’M PROUD OF IT’ Associate Publisher / Executive Editor • Jason Parsley [email protected] Kim Swan Editorial Art Director • Brendon Lies [email protected] Webmaster • Kimberly Swan fter struggling to keep his sexual [email protected] orientation a secret, Hig Roberts is the Social Media Director • Christiana Lilly first elite men’s Alpine skier to come Arts/Entertainment Editor • J.W. Arnold A [email protected] out as gay. In an interview with the New Food/Travel Editor • Rick Karlin York Times, Roberts said that by coming out Gazette News Editor • John McDonald publicly he hopes others are encouraged to HIV Editor • Sean McShee be themselves as well. Senior Photographer • J.R. Davis [email protected] “I just woke up one morning and I said, ‘Enough is enough,’” Roberts told the Times. Senior Feature Columnists Brian McNaught • Jesse Monteagudo “I love this sport more than anything — I’m so lucky and privileged to be doing this Correspondents Dori Zinn • Donald Cavanaugh — but I can’t go on another day not trying Christiana Lilly • John McDonald to achieve the person that I am meant to Denise Royal • David-Elijah Nahmod be. -

Rupaul's Drag Race

HALLELOO! “RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE” RETURNS TO LOGO FOR A NEW SEASON OF OUTRAGEOUS REALITY COMPETITION IN JANUARY 2012 The Nation’s Most Elite Drag Performers Compete for $100,000 Cash and the Title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar” To Tweet This Release: http://logo.to/s6k7Wu NEW YORK - November 14, 2011 – RuPaul and Logo are prepping an all-new squad of 13 lucky contestants who will vie for the crown, an unprecedented $100,000 cash prize and the coveted title of “America's Next Drag Superstar.” Logo’s smash-hit reality competition show “RuPaul’s Drag Race” returns January 2012. Over three trail-blazing seasons, “RuPaul’s Drag Race” has taken the country by storm, evolving from a cult hit to a certified pop culture phenomenon. With a devoted and diverse following ranging from soccer moms to Hollywood royalty, “RuPaul’s Drag Race” has become appointment television for viewers who can’t get enough of the outlandish fun, drama, “eleganza” and most of all, heart that comes with the show. "We challenged ourselves to make TV's most outrageous show even more outrageous,” said Executive Producer, RuPaul. “And I'm happy to report we've succeeded." This season, a new crop of top-tier drag hopefuls are strapping on their helmets and revving their engines for the most competitive drag race and biggest grand prize yet. The following are the 13 season four “RuPaul’s Drag Race” contestants: · Alisa Summers Tampa, FL #DragRaceAlisaSummers, @alisasummers · Chad Michaels San Diego, CA #DragRaceChadMichaels, @chadmichaels1 · Dida Ritz Chicago, IL #DragRaceDidaRitz, @HelloDiDa · Jiggly Caliente Queens, NY #DragRaceJigglyCaliente, @JigglyCaliente · Kenya Michaels Dorado, Puerto Rico #DragRaceKenyaMichaels, @Kenya_Michaels · Lashauwn Beyond Tampa, FL #DragRaceLashauwnBeyond, @LashauwnBeyond · Latrice Royale Ft. -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 a GOVERNMENT SERVICES

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 A GOVERNMENT SERVICES # Girl Names # Girl Names # Girl Names 1 A 1 Adelaide 4 Aisha 2 Aaisha 2 Adelle 1 Aisley 1 Aajah 1 Adelynn 1 Aislin 1 Aaliana 2 Adena 1 Aislinn 2 Aaliya 1 Adeoluwa 2 Aislyn 10 Aaliyah 1 Adia 1 Aislynn 1 Aalyah 1 Adiella 1 Aisyah 1 Aarona 5 Adina 1 Ai-Vy 1 Aaryanna 1 Adreana 1 Aiyana 1 Aashiyana 1 Adreanna 1 Aja 1 Aashna 7 Adria 1 Ajla 1 Aasiya 2 Adrian 1 Akanksha 1 Abaigeal 7 Adriana 1 Akasha 1 Abang 11 Adrianna 1 Akashroop 1 Abbegael 1 Adrianne 1 Akayla 1 Abbegayle 1 Adrien 1 Akaysia 15 Abbey 1 Adriene 1 Akeera 2 Abbi 3 Adrienne 1 Akeima 3 Abbie 1 Adyan 1 Akira 8 Abbigail 1 Aedan 1 Akoul 1 Abbi-Gail 1 Aeryn 1 Akrity 47 Abby 1 Aeshah 2 Alaa 3 Abbygail 1 Afra 1 Ala'a 2 Abbygale 1 Afroz 1 Alabama 1 Abbygayle 1 Afsaneh 1 Alabed 1 Abby-Jean 1 Aganetha 5 Alaina 1 Abella 1 Agar 1 Alaine 1 Abha 6 Agatha 1 Alaiya 1 Abigael 1 Agel 11 Alana 83 Abigail 2 Agnes 1 Alanah 1 Abigale 1 Aheen 4 Alanna 1 Abigayil 1 Ahein 2 Alannah 4 Abigayle 1 Ahlam 1 Alanta 1 Abir 2 Ahna 1 Alasia 1 Abrial 1 Ahtum 1 Alaura 1 Abrianna 1 Aida 1 Alaya 3 Abrielle 4 Aidan 1 Alayja 1 Abuk 2 Aideen 5 Alayna 1 Abygale 6 Aiden 1 Alaysia 3 Acacia 1 Aija 1 Alberta 1 Acadiana 1 Aika 1 Aldricia 1 Acelyn 1 Aiko 2 Alea 1 Achwiel 1 Aileen 7 Aleah 1 Adalien 1 Aiman 1 Aleasheanne 1 Adana 7 Aimee 1 Aleea 2 Adanna 2 Aimée 1 Aleesha 2 Adara 1 Aimie 2 Aleeza 1 Adawn-Rae 1 Áine 1 Aleighna 1 Addesyn 1 Ainsleigh 1 Aleighsha 1 Addisan 12 Ainsley 1 Aleika 10 Addison 1 Aira 1 Alejandra 1 Addison-Grace 1 Airianna 1 Alekxandra 1 Addyson 1 Aisa -

Drag Artist Interviews, 2019

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Southern Illinois University Edwardsville SPARK SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity 2020 Drag Artist Interviews, 2019 Ezra Temko [email protected] Adam Loesch SIUE, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://spark.siue.edu/siue_fac Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Temko, Ezra, Adam Loesch, et al. 2020. “Drag Artist Interviews, 2019.” Sociology of Drag, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Spring. Available URL (http://www.ezratemko.com/drag/interviewtranscripts/). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SPARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of SPARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Drag Artist Interviews, 2019 To cite this dataset as a whole, the following reference is recommended: Temko, Ezra, Adam Loesch, et al. 2020. “Drag Artist Interviews, 2019.” Sociology of Drag, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Spring. Available URL (http://www.ezratemko.com/drag/interviewtranscripts/). To cite individual interviews, see the recommended reference(s) at the top of the particular transcript(s). Interview -

Rupaul's Drag Race All Stars Season 2

Media Release: Wednesday August 24, 2016 RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE ALL STARS SEASON 2 TO AIR EXPRESS FROM THE US ON FOXTEL’S ARENA Premieres Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm Hot off the heels of one of the most electrifying seasons of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Mama Ru will return to the runway for RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 and, in a win for viewers, Foxtel has announced it will be airing express from the US from Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm on a new channel - Arena. In this second All Stars instalment, YouTube sensation Todrick Hall joins Carson Kressley and Michelle Visage on the judging panel alongside RuPaul for a season packed with more eleganza, wigtastic challenges and twists than Drag Race has ever seen. The series will also feature some of RuPaul’s favourite celebrities as guest judges, including Raven- Symone, Ross Matthews, Jeremy Scott, Nicole Schedrzinger, Graham Norton and Aubrey Plaza. Foxtel’s Head of Channels, Stephen Baldwin commented: “We know how passionate RuPaul fans are. Foxtel has been working closely with the production company, World of Wonder, and Passion Distribution and we are thrilled they have made it possible for the series to air in Australia just hours after its US telecast.” RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 will see 10 of the most celebrated competitors vying for a second chance to enter Drag Race history, and will be filled with plenty of heated competition, lip- syncing for the legacy and, of course, the All-Stars Snatch Game. The All Stars queens hoping to earn their place among Drag Race Royalty are: Adore Delano (S6), Alaska (S5), Alyssa Edwards (S5), Coco Montrese (S5), Detox (S5), Ginger Minj (S7), Katya (S7), Phi Phi O’Hara (S4), Roxxxy Andrews (S5) and Tatianna (S2). -

June 4, 5 in 1991, Marchers Were Taunted, Personally Wants to Marry His Part Buffalo's Gay Pride Celebra Chased and Verbally Assaulted

Partnerships The Gay Alliance appreciates the continuing partnership of businesses within our community who support our mission and vision. Platinum: MorganStanley Smith Barney Gold: Met life Silver: Excenus+' lesbians in New York State." NIXON PEA BOOYt1r State representatives Like Buf The outdoor rally in Albany on May 9. Photo: Ove Overmyer. More photos on page 18. falo area Assembly member Sam Hoyt followed Bronson on stage, -f THE JW:HBLDR as well as Manhattan Sen. Tom ftOCHUUII.FORUM lltW tRC Marriage Equality and GENDA get equal billing Duane and Lieutenant Gover .-ew ..A..Ulli.LIItlletil nor Bob Duffy; former mayor of at Equality and Justice Day; marriage bill's Rochester. TOMPKINrS future in Senate is still unclear "Marriage equality is a basic issue of civ.il rights," Duffy told By Ove Overmyer Closet press time, it was unclear a cheering crowd. "Nobody in Bronze: Albany, N.Y. - On May 9, when or if Governor Cuomo chis scare should ever question nearly 1,200 LGBT advocates would introduce the bill in rhe or underestimate Governor Cuo and allies gathered in the Empire Republican-dominated Senate. mo's commitment to marriage equality. The vernorhas made Kodak State Plaza Convention Center He has scared char he will �? underneath the state house in not do so unless there are enough marriage equality one of his top le Albany for what Rochester area voces to pass the legislation. three zislacive issues chis/ear." 0ut�t.W. Assembly member Harry Bron On May 9, activists from Dutfy acknowledge the son called "a historic day." every corner of the state, from difficulties that a marriage bill Assembly member Danny Buffalo to Montauk Pc.