Loperfido 2018 NLR Postpr.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real Democracy in the Occupy Movement

NO STABLE GROUND: REAL DEMOCRACY IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT ANNA SZOLUCHA PhD Thesis Department of Sociology, Maynooth University November 2014 Head of Department: Prof. Mary Corcoran Supervisor: Dr Laurence Cox Rodzicom To my Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is an outcome of many joyous and creative (sometimes also puzzling) encounters that I shared with the participants of Occupy in Ireland and the San Francisco Bay Area. I am truly indebted to you for your unending generosity, ingenuity and determination; for taking the risks (for many of us, yet again) and continuing to fight and create. It is your voices and experiences that are central to me in these pages and I hope that you will find here something that touches a part of you, not in a nostalgic way, but as an impulse to act. First and foremost, I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Laurence Cox, whose unfaltering encouragement, assistance, advice and expert knowledge were invaluable for the successful completion of this research. He was always an enormously responsive and generous mentor and his critique helped sharpen this thesis in many ways. Thank you for being supportive also in so many other areas and for ushering me in to the complex world of activist research. I am also grateful to Eddie Yuen who helped me find my way around Oakland and introduced me to many Occupy participants – your help was priceless and I really enjoyed meeting you. I wanted to thank Prof. Szymon Wróbel for debates about philosophy and conversations about life as well as for his continuing support. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

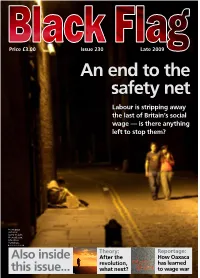

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

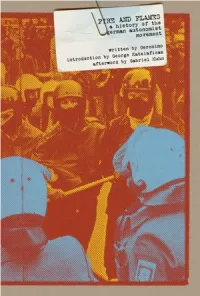

Fire and Flames

FIRE AND FLAMES FIRE AND FLAMES a history of the german autonomist movement written by Geronimo introduction by George Katsiaficas translation and afterword by Gabriel Kuhn FIRE AND FLAMES: A History of the German Autonomist Movement c. 2012 the respective contributors. This edition c. 2012 PM Press Originally published in Germany as: Geronimo. Feuer und Flamme. Zur Geschichte der Autonomen. Berlin/Amsterdam: Edition ID-Archiv, 1990. This translation is based on the fourth and final, slightly revised edition of 1995. ISBN: 978-1-60486-097-9 LCCN: 2010916482 Cover and interior design by Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org Images provided by HKS 13 (http://plakat.nadir.org) and other German archives. PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the USA on recycled paper by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, MI. www.thomsonshore.com CONTENTS Introduction 1 Translator’s Note and Glossary 9 Preface to the English-Language Edition 13 Background 17 ------- I. THE EMERGENCE OF AUTONOMOUS POLITICS IN WEST GERMANY 23 A Taste of Revolution: 1968 25 The Student Revolt 26 The Student Revolt and the Extraparliamentary Opposition 28 The Politics of the SDS 34 The Demise of the SDS 35 Militant Grassroots Currents 37 What Did ’68 Mean? 38 La sola soluzione la rivoluzione: Italy’s Autonomia Movement 39 What Happened in Italy in the 1960s? 39 From Marxism to Operaismo 40 From Operaio Massa to Operaio Sociale 42 The Autonomia Movement of 1977 43 Left Radicalism in the 1970s 47 “We Want Everything!”: Grassroots Organizing in the Factories 48 The Housing Struggles 52 The Sponti Movement at the Universities 58 A Short History of the K-Groups 59 The Alternative Movement 61 The Journal Autonomie 63 The Urban Guerrilla and Other Armed Groups 66 The German Autumn of 1977 69 A Journey to TUNIX 71 II. -

What Remains of the Italian Left of the 1970S? Jonathan Mullins

What Remains of the Italian Left of the 1970s? Jonathan Mullins Suddenly a photograph reaches me; it animates me and I animate it. So that is how I must name the attraction which makes it exist: an animation. The photograph itself is in no way animated (I do not believe in ‘life-like’ photographs), but it animates me: this is what creates every adventure. —Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida1 In September 1977, 20,000 young leftists descended upon Bologna for a convention at the Palasport stadium. The convention is largely identified with the end of the movement of 1977, in which youth on the far left broke with the Italian Communist Party (PCI), ridiculed institutional politics and the very idea of the social contract, and adopted forms of direct action. It is known for its mass protests, which usually ended in confrontations with the police in the streets, and for its broadcasts, via free radio stations, of messages of refusal that mixed aesthetic forms and political discourse. These young people had come to Bologna, the historical stronghold of the PCI, to protest the police repression of the movement, to re-vitalize collective forms of dissent and just be together. This scene was one of the last hurrahs of non-violent, collective far leftist revolt of 1970s Italy. It was captured in forty- nine minutes of unedited 16mm footage by the commercial production company Unitelefilm that is held at the Audio-Visual Archive for Democratic and Labor Movements (AAMOD) in Rome.2 The footage is remarkable for its recording of what happened on the margins of the Palasport convention and not the convention itself; the viewer never sees any of the orations, banners or charged publics that gathered at the Palasport stadium where the convention took place. -

STUDENTS.Pdf

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Student movements Author(s) Dooley, Brendan Editor(s) Stearns, Peter N. Publication date 2001 Original citation Dooley, B. (2001) 'Student movements', in Stearns, P. M. (ed.) Encyclopedia of European Social History. New York: Gale Group. pp. 301-310. Type of publication Book chapter Link to publisher's http://www.cengage.com/search/productOverview.do;jsessionid=A629B version B39D6DFA2EC61700F318D779247?N=197+4294916402&Ntk=P_EPI &Ntt=1803783465183769497013824211871588061963&Ntx=mode%2 Bmatchallpartial Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2001, Gale Group, a part of Cengage Learning, Inc. Reproduced by permission. www.cengage.com/permissions Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/3663 from Downloaded on 2021-09-28T15:45:15Z 1 STUDENT MOVEMENTS When French students took to the streets once again in October, 1998, they brought to a close a thirty-year period of academic unrest that has left an indelible mark on modern culture. To the extent that students as a group and student movements as a category of social action can be identified throughout European culture from the Renaissance to the present, this most recent period in the history of student movements has been unique. Nonetheless, coordinated behavior on the part of those enrolled in educational institutions has always played an important role in larger processes in society. Students alone, as a social elite with specific requirements and specific connections to the institutions of power, have created episodes of protest with a lasting impact on the lives of subsequent generations of students as well as on their societies at large. -

Picture That Would Be Crucial for the Author

VU Research Portal Revolt and crisis in Greece: Between a Present Yet to Pass and a Future Still to Come Dalakoglou, D.; Vradis, A. 2011 document license CC BY-ND Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Dalakoglou, D., & Vradis, A. (Eds.) (2011). Revolt and crisis in Greece: Between a Present Yet to Pass and a Future Still to Come. AK Press. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 REVOLT AND CRISIS IN GREECE BETWEEN A PRESENT YET TO PASS AND A FUTURE STILL TO COME How does a revolt come about and what does it leave behind? What impact does it have on those who participate in it and those who simply watch it? Is the Greek revolt of December 2008 confined to the shores of the Mediterranean, or are there lessons we can bring to bear on social action around the globe? Revolt and Crisis in Greece: Between a Present Yet to Pass and a Future Still to Come is a collective attempt to grapple with these questions. -

Notes Towards Autonomous Geographies: Creation, Resistance and Self-Management As Survival Tactics Jenny Pickerill1* and Paul Chatterton2

Progress in Human Geography 30, 6 (2006) pp. 1–17 Notes towards autonomous geographies: creation, resistance and self-management as survival tactics Jenny Pickerill1* and Paul Chatterton2 1Department of Geography, Leicester University, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK 2Department of Geography, Leeds University, University Road, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Abstract: This paper’s focus is what we call ‘autonomous geographies’ – spaces where there is a desire to constitute non-capitalist, collective forms of politics, identity and citizenship. These are created through a combination of resistance and creation, and a questioning and challenging of dominant laws and social norms. The concept of autonomy permits a better understanding of activists’ aims, practices and achievements in alter-globalization movements. We explore how autonomous geographies are multiscalar strategies that weave together spaces and times, constituting in-between and overlapping spaces, blending resistance and creation, and combining theory and practice. We flesh out two examples of how autonomous geographies are made through collective decision-making and autonomous social centres. Autonomous geographies provide a useful toolkit for understanding how spectacular protest and everyday life are combined to brew workable alternatives to life beyond capitalism. Key words: activism, alternative spaces, autonomy, creation, everyday life, interstitial, localization, resistance. I Introduction increasingly employed by anti-capitalist This paper is about what we call activists such as the Wombles, Disobidientis ‘autonomous geographies’ – those spaces and Dissent! to structure and articulate their where people desire to constitute non- practices and aims. At the same time, a rein- capitalist, egalitarian and solidaristic forms of vigoration and reinterpretation of autonomist political, social, and economic organization Marxism has provided a pathway towards a through a combination of resistance and cre- more socially just society (Cleaver, 1979; ation. -

Download Download

Left History 13_1 (final) 9/24/08 9:44 AM Page 77 The Environmental Question, Employment, and Development in Italy’s Left, 1945-19901 Wilko Graf von Hardenberg & Paolo Pelizzari Post-war Italy’s political organisations’ attitude towards environmental issues is closely correlated to how the country transformed from a merely agrarian society to one of the world’s richest industrial actors as well as to how its governments managed development. In view of the role of the social-Communist opposition in shaping the country’s cultural and social features we are persuaded that a better understanding of that process has to pass through an analysis of how the repre- sentatives of the workers’ movement approached the environmental question and the Italian model of development: an approach that was deeply influenced by a political vision favouring industrialisation, employment, and production.2 After World War II (WWII), and despite being entrenched in a frame- work deeply marked by the Cold War, the social-Communist left became an impor- tant political actor positing itself as a force of renewal and vouching for an alter- native developmental model opposed to that outlined by laissez-faire capitalism. Of course, its behaviour changed over time according to the country’s economic situ- ation. For instance, since the post-war reconstruction—from the ‘economic mir- acle’ and youth contestation until the energy crisis of the 1970s and the free-trade policies of the following decade—the Italian left faced several complex environ- mental problems. This complexity, together with the length of the historical peri- od considered, has not facilitated a simple historical narrative. -

Militant Protest and Practices of the State in France and the Federal Republic of Germany, 1968-1977

Under the Paving Stones: Militant Protest and Practices of the State in France and the Federal Republic of Germany, 1968-1977 Luca Provenzano Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Luca Provenzano All Rights Reserved Abstract Under the Paving Stones: Militant Protest and Practices of the State in France and the Federal Republic of Germany, 1968-1977 This dissertation investigates the protest cultures of social revolutionary groups during and after the events of 1968 in France and West Germany before inquiring into how political officials and police responded to the difficulties of maintaining public order. The events of 1968 led revolutionaries in both France and West Germany to adopt new justifications for militant action based in heterodox Marxism and anti-colonial theory, and to attempt to institutionalize new, confrontational modes of public protest that borrowed ways of knowing urban space, tactics, and materials from both the working class and armed guerrilla movements. Self-identifying revolutionaries and left intellectuals also institutionalized forums for the investigation of police interventions in protests on the basis of testimonies, photography, and art. These investigative committees regularly aimed to exploit the resonance of police violence to promote further cycles of politicization. In response, political officials and police sought after 1968 to introduce and to reinforce less ostentatious, allegedly less harmful means of crowd control and dispersion that could inflict suffering without reproducing the spectacle of mass baton assaults and direct physical confrontations—means of physical constraint less susceptible to unveiling as violence. -

Precarious Rhapsody: Semocapitalism & the Pathologies

Precarious Rhapsody Semiocapitalism and the pathologies of the post-alpha generation Franco “Bifo” Berardi <.:.Min0r.:.> .c0mp0siti0ns. Precarious Rhapsody Semiocapitalism and the pathologies of the post-alpha generation Franco “Bifo” Berardi ISBN 978-1-57027-207-3 Edited by Erik Empson & Stevphen Shukaitis Translated by Arianna Bove, Erik Empson, Michael Goddard, Giuseppina Mecchia, Antonella Schintu, and Steve Wright Bifo extends special thanks to Arianna, Erik and Stevphen for making this publication possible. Thanks to the 1750 subscribers of the netzine (www.rekombinant.org) who have been reading my postings during the last eight years, and have helped in creating a large deterritorialized com- munity of free thinkers. Minor Compositions London 2009 Distributed by Autonomedia PO Box 568 Williamsburgh Station Brooklyn, New York 11211-0568 USA www.minorcompositions.info [email protected] Table of Contents 00. Bifurcations 7 The end of modern politics 01. When the future began 14 The social conflict and political framework • From ironic messages to hyperbolic messages • Don’t worry about your future, you don’t have one • The nightmare after the end of the dream • The year of premonition 02. Info-labor/precarization 30 Schizo-economy • The psychic collapse of the economy • The info- sphere and the social mind • Panic war and semio-capital • Splatterkap- italismus 03. The warrior the merchant the sage 56 The movement against the privatization of knowledge • From intellec- tuals to cognitarians • From the organic intellectual to the general intel- lect • The cognitariat and recombination • The cognitariat against capitalist cyber-time • The autonomy of science from power • Intellec- tuals, cognitarians and social composition 04. -

In Paolo Virno, Grammar of the Multitude

A Grammar of the Multitude For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life Paolo Virno Foreword by Sylvère Lotringer Translated from the Italian Isabella Bertoletti James as!aito Andrea asson SEMIOTEXT(E) FOREIGN AGENTS SERIES F()6#()'" #e$ the Multitude Paolo Virno’s A Grammar of the Multitude is a short book, but it casts a very long shadow. Behind it looms the entire history of the labor move- ment and its heretical wing, talian !workerism" #operaismo$, which rethought %ar&ism in light of the struggles of the '()*s and '(7*s. +or the most ,art, though, it looks forward. -bstract intelligence and imma- terial signs have become the ma.or ,roductive force in the !,ost-+ordist” economy we are living in and they are dee,ly affecting contem,orary structures and mentalities. Virno’s essay e&amines the increased mobility and versatility of the new labor force whose work-time now virtually e&tends to their entire life. /he !multitude" is the kind of subjective con- figuration that this radical change is liberating, raising the ,olitical 0ues- tion of what we are capable of. Operaismo #workerism$ has a ,arado&ical relation to traditional %ar&- ism and to the official labor movement because it refuses to consider work as the defining factor of human life. %ar&ist analysis assumes that what makes work alienating is ca,italist e&,loitation, but o,eraists reali1ed that it is rather the reduction of life to work. Parado&ically, !workerists" are against work, against the socialist ethics that used to e&alt its dignity. -

The Italian Communist Party and the Movements of 1972-7

‘Rejecting all adventurism’: The Italian Communist Party and the movements of 1972-9 Abstract The history of the Italian Communist Party in the 1960s and 1970s was marked by the party’s engagement with a succession of radical competitors. Following Sidney Tarrow, I argue that the party benefited from its engagement with the ‘cycle of contention’ which culminated in the Hot Autumn of 1969. However, a second cycle can also be identified, running from 1972 to 1979 and fuelled by ‘autonomist’ readings of Marxism. The paper contrasts the party’s constructive engagement with the first cycle of contention and its hostile engagement with this second group of movements. It identifies both ideological and conjunctural reasons for the Italian communist party’s failure to engage constructively with the second cycle of contention, situating this within the context of Enrico Berlinguer’s leadership of the party. Lastly, it argues that this hostile engagement was a major contributory factor to the suppression of the movements; the growth of ‘armed struggle’ groups; and the decline of the Italian communist party itself. It is argued that the orientation of a ‘gatekeeper’ party at a particular historical conjuncture may have far-reaching effects, both for the party itself and for society more broadly. Keywords: Italian Communist Party, cycle of contention, gatekeeper, Autonomia, historic compromise. Closed systems and gatekeepers: the Italian case Sidney Tarrow’s model of the ‘protest cycle’ or ‘cycle of contention’, developed originally to describe the rise and fall of Italian radical movements in the late 1960s, identifies how new and challenging protest tactics can be absorbed into the political mainstream, even while the social movements which have given rise to these new tactics are denied legitimacy and marginalised.