38 CHAPTER 2: ITALIAN AUTONOMIA Like

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real Democracy in the Occupy Movement

NO STABLE GROUND: REAL DEMOCRACY IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT ANNA SZOLUCHA PhD Thesis Department of Sociology, Maynooth University November 2014 Head of Department: Prof. Mary Corcoran Supervisor: Dr Laurence Cox Rodzicom To my Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is an outcome of many joyous and creative (sometimes also puzzling) encounters that I shared with the participants of Occupy in Ireland and the San Francisco Bay Area. I am truly indebted to you for your unending generosity, ingenuity and determination; for taking the risks (for many of us, yet again) and continuing to fight and create. It is your voices and experiences that are central to me in these pages and I hope that you will find here something that touches a part of you, not in a nostalgic way, but as an impulse to act. First and foremost, I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Laurence Cox, whose unfaltering encouragement, assistance, advice and expert knowledge were invaluable for the successful completion of this research. He was always an enormously responsive and generous mentor and his critique helped sharpen this thesis in many ways. Thank you for being supportive also in so many other areas and for ushering me in to the complex world of activist research. I am also grateful to Eddie Yuen who helped me find my way around Oakland and introduced me to many Occupy participants – your help was priceless and I really enjoyed meeting you. I wanted to thank Prof. Szymon Wróbel for debates about philosophy and conversations about life as well as for his continuing support. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Timothy Campbell, introduction to Bios. Biopolitics and Philosophy by Roberto Esposito (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), vii. 2. David Graeber, “The Sadness of post- Workerism or Art and Immaterial Labor Conference a Sort of Review,” The Commoner, April 1, 2008, accessed May 22, 2011, http://www.commoner.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/graeber_ sadness.pdf. 3. Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended 1975–1976 (New York: Picador, 2003), 210, 211, 212. 4. Ibid., 213. 5. Racism works for the state as “a break into the domain of life that is under power’s control: the break between what must live and what must die” (ibid., 254). 6. Ibid., 212. 7. Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 219. 8. Ibid., 224. 9. Ibid., 229. 10. See Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998) and State of Exception (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005). 11. Esposito, Bios. Biopolitics and Philosophy, 14, 15. 12. Ibid., 147. 13. Laurent Dubreuil, “Leaving Politics. Bios, Zo¯e¯ Life,” Diacritics 36.2 (2006): 88. 14. Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude (New York: Semiotext[e], 2004), 81. Chapter 1 1. Catalogo Bolaffi delle Fiat, 1899–1970; repertorio completo della produzione automobilistica Fiat dalle origini ad oggi, ed. Angelo Tito Anselmi (Turin: G. Bolaffi , 1970), 15. 2. Gwyn A. Williams, introduction to The Occupation of the Factories: Italy 1920, by Paolo Spriano (London: Pluto Press, 1975), 9. See also Giorgio Porosini, 174 ● Notes Il capitalismo italiano nella prima guerra mondiale (Florence: La Nuova Italia Editore, 1975), 10–17, and Rosario Romero, Breve storia della grande industria in Italia 1861–1961 (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1988), 89–97. -

The Winding Paths of Capital

giovanni arrighi THE WINDING PATHS OF CAPITAL Interview by David Harvey Could you tell us about your family background and your education? was born in Milan in 1937. On my mother’s side, my fam- ily background was bourgeois. My grandfather, the son of Swiss immigrants to Italy, had risen from the ranks of the labour aristocracy to establish his own factories in the early twentieth Icentury, manufacturing textile machinery and later, heating and air- conditioning equipment. My father was the son of a railway worker, born in Tuscany. He came to Milan and got a job in my maternal grand- father’s factory—in other words, he ended up marrying the boss’s daughter. There were tensions, which eventually resulted in my father setting up his own business, in competition with his father-in-law. Both shared anti-fascist sentiments, however, and that greatly influenced my early childhood, dominated as it was by the war: the Nazi occupation of Northern Italy after Rome’s surrender in 1943, the Resistance and the arrival of the Allied troops. My father died suddenly in a car accident, when I was 18. I decided to keep his company going, against my grandfather’s advice, and entered the Università Bocconi to study economics, hoping it would help me understand how to run the firm. The Economics Department was a neo- classical stronghold, untouched by Keynesianism of any kind, and no help at all with my father’s business. I finally realized I would have to close it down. I then spent two years on the shop-floor of one of my new left review 56 mar apr 2009 61 62 nlr 56 grandfather’s firms, collecting data on the organization of the production process. -

Bologna and the Trauma of March 1977: the Intellettuali Contro and Their Resistance to the Local Communist Party

Bologna and the Trauma of March 1977: the Intellettuali Contro and Their Resistance to the Local Communist Party Andrea Hajek Institute of Germanic & Romance Studies (IGRS), University of London Chi ha lanciato un sasso alla manifestazione di Roma lo ha lanciato contro i movimenti di donne e uomini che erano in piazza. These are the first lines of a public letter published inLa Repubblica on December 16, 2010, written by author Roberto Saviano in the aftermath of a violent demonstration against Silvio Berlusconi’s narrow victory in the vote of confidence of December 14, 2010, which brought back memories of the anni di piombo.1 The letter condemned the aggres- sive instigations of the so-called ‘black blocks,’ and was an attempt to dissuade the students, who in those months were protesting against an educational reform, from resorting to violent behavior. To some extent, Saviano’s criticism recalls Pier Paolo Pasolini’s famous reaction to the Valle Giulia clashes in Rome, on March 1, 1968, where he publicly sided with the police forces and against the students.2 Nearly a decade later a new student movement arose, which not only reacted against authoritative manifestations of the state, but also turned against traditional left-wing parties and unions. According to Jennifer Burns, this period reflects a “withdrawal of [literary-political] com- mitment to macro-political, left/right-wing ideologies, in favour of micro-political, community-based initiatives.”3 Although the relation between the alternative left-wing milieu and the political parties of the left had worsened throughout the 1970s, the death, in 1977, of a young activist constituted an important and deci- sive rupture. -

Post/Autonomia

Progressive nostalgia. Appropriating memories of protest and contention in contemporary Italy Andrea Hajek, PhD Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory IGRS, University of London Abstract More than 30 years ago the violent death - on 11 March 1977 - of a left-wing student in the Italian city of Bologna brought an end to a student protest movement, the ‘Movement of ’77’. Today nostalgia dominates public commemorations of the movement as it manifested itself in Bologna. However, this memory is not an exclusive memory of the 1977 generation. A number of young, left-wing activists that draw on the myth of 1977 in Bologna and in particular on the memory of the local Workers Autonomy faction appropriate this memory in a similarly nostalgic manner. This article then explores the value of nostalgia in generational memory: how does it relate to past, present and future, and to what extent does it influence processes of identity formation among youth groups? I argue that nostalgia is more than a longing for the past, and that it can be conceived as progressive and future-orientated, providing empowerment for specific social groups. Keywords Nostalgia, generational memory, 1970s, Italian student movements, Workers Autonomy. Word count: ca. 6.000 (incl. notes and references) 1 Progressive nostalgia. Appropriating memories of protest and contention in contemporary Italy ‘Pagherete caro, pagherete tutto!’1 On 12 March 2011, this slogan reverberated in the streets of the Italian city of Bologna, 34 years after left-wing student Francesco Lorusso was shot dead by police during student protests. Lorusso’s disputed and unresolved death on 11 March 1977 - for which the police officer who shot him was never tried - as well as the violent incidents that subsequently kept Bologna in a state of high tension, have left a deep wound in the city, in particular among Lorusso’s former companions and friends. -

Materials from Lottacontinua on Alfred Sohn-Rethel

Materials from Lotta Continua on Alfred Sohn-Rethel Translated by Richard Braude 1. Costanzo Preve, Commodities and Thought: Sohn-Rethel’s Book. (LC, 5 August 1977, p. 6) 2. Costanzo Preve, Manual and Intellectual Labour: Towards Understanding Sohn-Rethel. (LC, 5 August 1977, pp. 6–7) 3. Costanzo Preve, Sohn-Rethel in Italy. (LC, 5 August 1977, p. 7) 4. Costanzo Preve, Never Become an Academic Baron. (LC, 5 August 1977, pp. 6–7) 5. ‘F.D.’, Reading This Page. (LC, 3 September 1977, p. 7) 6. Pier Aldo Rovatti, Towards A Materialist Theory of Knowledge. (LC, 3 September 1977, pp. 6–7) 7. Antonio Negri, The Working Class and Transition. (LC, 6 September 1977, pp. 6–7) 8. Francesco Coppellotti, On Sohn-Rethel. (LC, 10 September 1977, p. 5) Translator’s note: Costanzo Previ is cited as the ‘editor’ of the pages in the 5 August issue. From the style, my guess is that he wrote one long piece which was then split into three and touched up by the paper’s editors. The third piece (‘Sohn-Rethel in Italy’) is in his characteristic tone; the joke in the first piece about auto-reduction feels less like him. As for the identity of ‘F.D.’, the author of the introductory note of the 3 September issue, I really have no idea. ∵ 1 Costanzo Preve, Commodities and Thought: Sohn-Rethel’s Book (LC, 5 August 1977, p. 6) In speaking about Alfred Sohn-Rethel’s book (Intellectual and Manual Labour, Feltrinelli, 1977) one can first of all say ‘it goes far beyond the intentions’ of Marx, Engels and Lenin. -

The Autonomy of Struggles and the Self-Management of Squats: Legacies of Intertwined Movements Miguel A

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 11 (1): 178 – 199 (July 2019) Martínez, The Autonomy of Struggles The autonomy of struggles and the self-management of squats: legacies of intertwined movements Miguel A. Martínez Abstract How do squatters’ movements make a difference in urban politics? Their singularity in European cities has often been interpreted according to the major notion of ‘autonomy’. However, despite the recent upsurge of studies about squatting (Cattaneo et al. 2014, Katsiaficas 2006, Martínez et al. 2018, Van der Steen et al. 2014), there has not been much clarification of its theoretical, historical and political significance. Autonomism has also been identified as one of the main ideological sources of the recent global justice and anti-austerity movements (Flesher 2014) after being widely diffused among European squatters for more than four decades, which prompts a question about the meaning of its legacy. In this article, I first examine the political background of autonomism as a distinct identity among radical movements in Europe in general (Flesher et al. 2013, Wennerhag et al. 2018), and the squatters in particular—though not often explicitly defined. Secondly, I stress the social, feminist and anti-capitalist dimensions of autonomy that stem from the multiple and specific struggles in which squatters were involved over different historical periods. These aspects have been overlooked or not sufficiently examined by the literature on squatting movements. By revisiting relevant events and discourses of the autonomist tradition linked to squatting in Italy, Germany and Spain, its main traits and some contradictions are presented. Although political contexts indicate different emphases in each case, some common origins and transnational exchanges justify an underlying convergence and its legacies over time. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

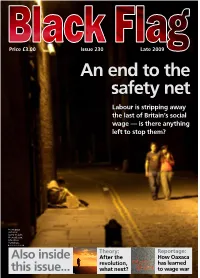

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

Works Cited – Films

Works cited – films Ali (Michael Mann, 2001) All the President’s Men (Alan J Pakula, 1976) American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1998) American History X (Tony Kaye, 1998) American Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000) American Splendor (Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini, 2003) Arlington Road (Mark Pellington, 1999) Being There (Hal Ashby, 1980) Billy Elliott (Stephen Daldry, 2000) Black Christmas (Bob Clark, 1975) Blow Out (Brian De Palma, 1981) Bob Roberts (Tim Robbins, 1992) Bowling for Columbine (Michael Moore, 2002) Brassed Off (Mark Herman, 1996) The Brood (David Cronenberg, 1979) Bulworth (Warren Beatty, 1998) Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003) Control Room (Jehane Noujaim, 2004) The China Syndrome (James Bridges, 1979) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) Clerks (Kevin Smith, 1994) Conspiracy Theory (Richard Donner, 1997) The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) The Corporation (Jennifer Abbott and Mark Achbar, 2004) Crumb (Terry Zwigoff, 1994) Dave (Ivan Reitman, 1993) The Defector (Raoul Lévy, 1965) La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960) Dr Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) Evil Dead II (Sam Raimi, 1987) 201 Executive Action (David Miller, 1973) eXistenZ (David Cronenberg, 1999) The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004) Falling Down (Joel Schumacher, 1993) Far From Heaven (Todd Haynes, 2002) Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999) The Firm (Sydney Pollack, 1993) The Fly (David Cronenberg, 1986) The Forgotten (Joseph Ruben, 2004) Friday the 13th -

Italian Communist Party

Manifesto Program of the (new) Italian Communist Party March 2008 We dedicate this Manifesto Program to all the heroes of the first wave of the world proletarian revolution. Commissione Provvisoria del Comitato Centrale del (nuovo)Partito comunista italiano Web site: http://lavoce-npci.samizdat.net email: [email protected] *** Delegazione: BP3 4, rue Lénine 93451 L’Île St Denis (Francia { XE “Francia” }) email: [email protected] Manifesto Program of the (new) Italian Communist Party (Preliminary note: With the asterisk (*) we indicate that this Manifesto Program is using a category, a concept that in our conception has a precise meaning that the reader cannot understand by the current meaning of the terms. The Manifesto Program itself will explain below what this category or concept means) Introduction The world we are living in is shaken by heavy con- is the transformation the humanity has to carry out. vulsions from end to end. They are the convulsions of The bourgeoisie imposes to the popular masses so the old world dying and the new one rising. The old cruel and unbearable conditions that the struggle world splits in two, one part going to die and the other against it explodes in thousand ways. Where the com- going to give birth to the communist society, a new munists are not yet able to be their direction, other phase in humanity’s history. classes are doing it, with the limits and forms consis- The bourgeoisie took advantage of the period of tent with their nature. decay the organized and conscious communist move- However, in the struggle to face the devastating ef- ment (*) went through in the second half of the last fects of the contradictions of capitalism, made again century. -

Fire and Flames

FIRE AND FLAMES FIRE AND FLAMES a history of the german autonomist movement written by Geronimo introduction by George Katsiaficas translation and afterword by Gabriel Kuhn FIRE AND FLAMES: A History of the German Autonomist Movement c. 2012 the respective contributors. This edition c. 2012 PM Press Originally published in Germany as: Geronimo. Feuer und Flamme. Zur Geschichte der Autonomen. Berlin/Amsterdam: Edition ID-Archiv, 1990. This translation is based on the fourth and final, slightly revised edition of 1995. ISBN: 978-1-60486-097-9 LCCN: 2010916482 Cover and interior design by Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org Images provided by HKS 13 (http://plakat.nadir.org) and other German archives. PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the USA on recycled paper by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, MI. www.thomsonshore.com CONTENTS Introduction 1 Translator’s Note and Glossary 9 Preface to the English-Language Edition 13 Background 17 ------- I. THE EMERGENCE OF AUTONOMOUS POLITICS IN WEST GERMANY 23 A Taste of Revolution: 1968 25 The Student Revolt 26 The Student Revolt and the Extraparliamentary Opposition 28 The Politics of the SDS 34 The Demise of the SDS 35 Militant Grassroots Currents 37 What Did ’68 Mean? 38 La sola soluzione la rivoluzione: Italy’s Autonomia Movement 39 What Happened in Italy in the 1960s? 39 From Marxism to Operaismo 40 From Operaio Massa to Operaio Sociale 42 The Autonomia Movement of 1977 43 Left Radicalism in the 1970s 47 “We Want Everything!”: Grassroots Organizing in the Factories 48 The Housing Struggles 52 The Sponti Movement at the Universities 58 A Short History of the K-Groups 59 The Alternative Movement 61 The Journal Autonomie 63 The Urban Guerrilla and Other Armed Groups 66 The German Autumn of 1977 69 A Journey to TUNIX 71 II. -

Social Factory”: on Women’S Work, Immaterial Labor, and Theoretical Recovery

Journeys in the Italian “social factory”: on women’s work, immaterial labor, and theoretical recovery David P. Palazzo, Hunter College, CUNY, [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the annual meeting of the Western Political Science Association, Las Vegas, NV, April 2-4, 2015. This is a work in-progress. Please do not quote without permission. Abstract This paper is about the location of women in the “social factory.” Their demand to be included in the class struggle derives from their development of this concept in the early 1970s. I provide an interpretation of their critique of the concept “immaterial labor” as developed in Hardt and Negri’s Empire trilogy, by examining the “social factory” as a historical category. I frame the discussion around initial formulations in Panzieri and Tronti as a useful heuristic for later depictions of the factory-society relation. In its simplest terms, these differences derive from an understanding of how “society” becomes a “factory.” This is, above all, a work of recovery by taking a journey into the workerist “social factory” in order to theoretically demonstrate the divergent paths and concerns that emerged from this group of thinkers around place of unwaged reproductive labor in “autonomous Marxism.” 2 It took years for the other subjects – men – to acknowledge the meaning of women’s denunciation – that is the immense feminine labor that went into reproducing them – and then for their behavior to change. Many remained deaf anyway… –Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Rustic and Ethical Introduction Social reproduction, reproductive labor, and the persistence of unwaged work pose specific problems for political theorists attempting to understand labor after the imposition of these categories by the “new women’s movement” some forty years ago.