Selections from Acf in the Tradition.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Hegemony and the Socialist International's Place in Interwar

02_EHQ 31/1 articles 30/11/00 1:53 pm Page 101 William Lee Blackwood German Hegemony and the Socialist International’s Place in Interwar European Diplomacy When the guns fell silent on the western front in November 1918, socialism was about to become a governing force throughout Europe. Just six months later, a Czech socialist could marvel at the convocation of an international socialist conference on post- war reconstruction in a Swiss spa, where, across the lake, stood buildings occupied by now-exiled members of the deposed Habsburg ruling class. In May 1923, as Europe’s socialist parties met in Hamburg, Germany, finally to put an end to the war-induced fracturing within their ranks by launching a new organization, the Labour and Socialist International (LSI), the German Communist Party’s main daily published a pull-out flier for posting on factory walls. Bearing the sarcastic title the International of Ministers, it presented to workers a list of forty-one socialists and the national offices held by them in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Poland, France, Sweden, and Denmark. Commenting on the activities of the LSI, in Paris a Russian Menshevik émigré turned prominent left-wing pundit scoffed at the new International’s executive body, which he sarcastically dubbed ‘the International Socialist Cabinet’, since ‘all of its members were ministers, ex-ministers, or prospec- tive ministers of State’.1 Whether one accepted or rejected its new status, socialism’s virtually overnight transformation from an outsider to a consummate insider at the end of Europe’s first total war provided the most striking measure of the quantum leap into what can aptly be described as Europe’s ‘social democratic moment’.2 Moreover, unlike the period after Europe’s second total war, when many of socialism’s basic postulates became permanently embedded in the post-1945 social-welfare-state con- European History Quarterly Copyright © 2001 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Timothy Campbell, introduction to Bios. Biopolitics and Philosophy by Roberto Esposito (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), vii. 2. David Graeber, “The Sadness of post- Workerism or Art and Immaterial Labor Conference a Sort of Review,” The Commoner, April 1, 2008, accessed May 22, 2011, http://www.commoner.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/graeber_ sadness.pdf. 3. Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended 1975–1976 (New York: Picador, 2003), 210, 211, 212. 4. Ibid., 213. 5. Racism works for the state as “a break into the domain of life that is under power’s control: the break between what must live and what must die” (ibid., 254). 6. Ibid., 212. 7. Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 219. 8. Ibid., 224. 9. Ibid., 229. 10. See Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998) and State of Exception (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005). 11. Esposito, Bios. Biopolitics and Philosophy, 14, 15. 12. Ibid., 147. 13. Laurent Dubreuil, “Leaving Politics. Bios, Zo¯e¯ Life,” Diacritics 36.2 (2006): 88. 14. Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude (New York: Semiotext[e], 2004), 81. Chapter 1 1. Catalogo Bolaffi delle Fiat, 1899–1970; repertorio completo della produzione automobilistica Fiat dalle origini ad oggi, ed. Angelo Tito Anselmi (Turin: G. Bolaffi , 1970), 15. 2. Gwyn A. Williams, introduction to The Occupation of the Factories: Italy 1920, by Paolo Spriano (London: Pluto Press, 1975), 9. See also Giorgio Porosini, 174 ● Notes Il capitalismo italiano nella prima guerra mondiale (Florence: La Nuova Italia Editore, 1975), 10–17, and Rosario Romero, Breve storia della grande industria in Italia 1861–1961 (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1988), 89–97. -

Beyond the Law of Value: Class Struggle and Socialisttransformation

chapter 11 Beyond the Law of Value: Class Struggle and Socialist Transformation If only one tenth of the human energy that is now expended on reform- ing capitalism, protesting its depredations and cobbling together elect- oral alliances within the arena of bourgeois politics could be channelled instead into an effective revolutionary/transformative political practice, one suspects that the era of socialist globalization would be close at hand … The objective, historical conditions for a socialist transformation are not only ripe; they have become altogether rotten. The global capital- ist order is presently in an advanced state of decay. The vital task today is to bring human consciousness and activity – the ‘subjective factor’ – into correspondence with the urgent need to confront and transform that objective reality.1 Such was my assessment in Global Capitalism in Crisis, published in the imme- diate aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008–09. Nearly a decade on, one must concede perforce that little progress has been made in accomplishing the vital task prescribed. The capitalist class has waged a remarkably success- ful campaign to suppress the emergence of a mass socialist workers movement capable of addressing the ‘triple crisis’ of twenty-first-century capitalism that was outlined in Chapter 1. In the face of persistent global economic malaise, growing inequality, accel- erating climate change, and worsening international relations portending world war, global capitalism has avoided a crisis of legitimacy proportionate to the dangers facing humanity. This anomaly speaks volumes about the power of ideology, as deployed by the main beneficiaries of the capitalist order, to ‘obscure social reality and deflect attention from the demonstrable connec- tions that exist between the capitalist profit system and the multiple crises of the contemporary world’.2 InThe German Ideology, Marx and Engels wrote: ‘The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas: i.e. -

The Winding Paths of Capital

giovanni arrighi THE WINDING PATHS OF CAPITAL Interview by David Harvey Could you tell us about your family background and your education? was born in Milan in 1937. On my mother’s side, my fam- ily background was bourgeois. My grandfather, the son of Swiss immigrants to Italy, had risen from the ranks of the labour aristocracy to establish his own factories in the early twentieth Icentury, manufacturing textile machinery and later, heating and air- conditioning equipment. My father was the son of a railway worker, born in Tuscany. He came to Milan and got a job in my maternal grand- father’s factory—in other words, he ended up marrying the boss’s daughter. There were tensions, which eventually resulted in my father setting up his own business, in competition with his father-in-law. Both shared anti-fascist sentiments, however, and that greatly influenced my early childhood, dominated as it was by the war: the Nazi occupation of Northern Italy after Rome’s surrender in 1943, the Resistance and the arrival of the Allied troops. My father died suddenly in a car accident, when I was 18. I decided to keep his company going, against my grandfather’s advice, and entered the Università Bocconi to study economics, hoping it would help me understand how to run the firm. The Economics Department was a neo- classical stronghold, untouched by Keynesianism of any kind, and no help at all with my father’s business. I finally realized I would have to close it down. I then spent two years on the shop-floor of one of my new left review 56 mar apr 2009 61 62 nlr 56 grandfather’s firms, collecting data on the organization of the production process. -

Post/Autonomia

Progressive nostalgia. Appropriating memories of protest and contention in contemporary Italy Andrea Hajek, PhD Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory IGRS, University of London Abstract More than 30 years ago the violent death - on 11 March 1977 - of a left-wing student in the Italian city of Bologna brought an end to a student protest movement, the ‘Movement of ’77’. Today nostalgia dominates public commemorations of the movement as it manifested itself in Bologna. However, this memory is not an exclusive memory of the 1977 generation. A number of young, left-wing activists that draw on the myth of 1977 in Bologna and in particular on the memory of the local Workers Autonomy faction appropriate this memory in a similarly nostalgic manner. This article then explores the value of nostalgia in generational memory: how does it relate to past, present and future, and to what extent does it influence processes of identity formation among youth groups? I argue that nostalgia is more than a longing for the past, and that it can be conceived as progressive and future-orientated, providing empowerment for specific social groups. Keywords Nostalgia, generational memory, 1970s, Italian student movements, Workers Autonomy. Word count: ca. 6.000 (incl. notes and references) 1 Progressive nostalgia. Appropriating memories of protest and contention in contemporary Italy ‘Pagherete caro, pagherete tutto!’1 On 12 March 2011, this slogan reverberated in the streets of the Italian city of Bologna, 34 years after left-wing student Francesco Lorusso was shot dead by police during student protests. Lorusso’s disputed and unresolved death on 11 March 1977 - for which the police officer who shot him was never tried - as well as the violent incidents that subsequently kept Bologna in a state of high tension, have left a deep wound in the city, in particular among Lorusso’s former companions and friends. -

Capitalism Has Failed — What Next?

The Jus Semper Global Alliance In Pursuit of the People and Planet Paradigm Sustainable Human Development November 2020 ESSAYS ON TRUE DEMOCRACY AND CAPITALISM Capitalism Has Failed — What Next? John Bellamy Foster ess than two decades into the twenty-first century, it is evident that capitalism has L failed as a social system. The world is mired in economic stagnation, financialisation, and the most extreme inequality in human history, accompanied by mass unemployment and underemployment, precariousness, poverty, hunger, wasted output and lives, and what at this point can only be called a planetary ecological “death spiral.”1 The digital revolution, the greatest technological advance of our time, has rapidly mutated from a promise of free communication and liberated production into new means of surveillance, control, and displacement of the working population. The institutions of liberal democracy are at the point of collapse, while fascism, the rear guard of the capitalist system, is again on the march, along with patriarchy, racism, imperialism, and war. To say that capitalism is a failed system is not, of course, to suggest that its breakdown and disintegration is imminent.2 It does, however, mean that it has passed from being a historically necessary and creative system at its inception to being a historically unnecessary and destructive one in the present century. Today, more than ever, the world is faced with the epochal choice between “the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large and the common ruin of the contending classes.”3 1 ↩ George Monbiot, “The Earth Is in a Death Spiral. It will Take Radical Action to Save Us,” Guardian, November 14, 2018; Leonid Bershidsky, “Underemployment is the New Unemployment,” Bloomberg, September 26, 2018. -

Works Cited – Films

Works cited – films Ali (Michael Mann, 2001) All the President’s Men (Alan J Pakula, 1976) American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1998) American History X (Tony Kaye, 1998) American Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000) American Splendor (Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini, 2003) Arlington Road (Mark Pellington, 1999) Being There (Hal Ashby, 1980) Billy Elliott (Stephen Daldry, 2000) Black Christmas (Bob Clark, 1975) Blow Out (Brian De Palma, 1981) Bob Roberts (Tim Robbins, 1992) Bowling for Columbine (Michael Moore, 2002) Brassed Off (Mark Herman, 1996) The Brood (David Cronenberg, 1979) Bulworth (Warren Beatty, 1998) Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003) Control Room (Jehane Noujaim, 2004) The China Syndrome (James Bridges, 1979) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) Clerks (Kevin Smith, 1994) Conspiracy Theory (Richard Donner, 1997) The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) The Corporation (Jennifer Abbott and Mark Achbar, 2004) Crumb (Terry Zwigoff, 1994) Dave (Ivan Reitman, 1993) The Defector (Raoul Lévy, 1965) La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960) Dr Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) Evil Dead II (Sam Raimi, 1987) 201 Executive Action (David Miller, 1973) eXistenZ (David Cronenberg, 1999) The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004) Falling Down (Joel Schumacher, 1993) Far From Heaven (Todd Haynes, 2002) Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999) The Firm (Sydney Pollack, 1993) The Fly (David Cronenberg, 1986) The Forgotten (Joseph Ruben, 2004) Friday the 13th -

To Look at the Digital Booklet for the Production!

PARIS COMMUNE Written by Steve Cosson and Michael Friedman Songs translated and adapted by Michael Friedman 1. Le Temps des Cerises – Kate Buddeke 2. La Canaille - Kate Buddeke 3. I Love the Military - Charlotte Dobbs 4. Song of May - Kate Buddeke, Aysan Celik, Rebecca Hart, Nina Hellman, Daniel Jenkins, Brian Sgambati, Sam Breslin Wright, The Paris Commune Original Cast Recording Ensemble 5. Yodeling Ducks – Aysan Celik, Daniel Jenkins 6. God of the Bigots – Kate Buddeke, Aysan Celik, Rebecca Hart, Nina Hellman, Daniel Jenkins, Brian Sgambati, Sam Breslin Wright, The Paris Commune Original Cast Recording Ensemble 7. The Internationale – Kate Buddeke, Aysan Celik, Rebecca Hart, Nina Hellman, Daniel Jenkins, Brian Sgambati, Sam Breslin Wright, The Paris Commune Original Cast Recording Ensemble 8. Ah! Je Veux Vivre – Charlotte Dobbs, Nina Hellman, Daniel Jenkins, Brian Sgambati, Sam Breslin Wright 9. Mon Homme – Aysan Celik 10. The Captain – Kate Buddeke, Aysan Celik, Rebecca Hart, Nina Hellman, Daniel Jenkins, Brian Sgambati, Sam Breslin Wright, The Paris Commune Original Cast Recording Ensemble 11. The Bloody Week — Kate Buddeke 12. Le Temps des Cerises (reprise) — Kate Buddeke, Jonathan Raviv, Aysan Celik, Rebecca Hart, Nina Hellman, Daniel Jenkins, Brian Sgambati, Sam Breslin Wright, The Paris Commune Original Cast Recording Ensemble Nina Hellman, Jeanine Serralles, Sam Breslin Wright, Aysan Celik, Daniel Jenkins, Brian Sgambati SYNOPSIS violent, repressive and bloody episodes of France’s Paris Commune tells the story of the first European history. socialist revolution, an attempt to completely re-order society – government, co-operative ownership of At the start of the show, two actors set the scene. It’s business, education, the rights of women, even the hours 1871. -

The Case of the French Review Socialisme Ou Barbarie (1948-1965)

Journalism and Mass Communication, September 2016, Vol. 6, No. 9, 499-511 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2016.09.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Acting and Thinking as a Revolutionary Organ: The Case of the French Review Socialisme ou Barbarie (1948-1965) Christophe Premat Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden The aim of the article is to analyze the evolution of a radical left group in France that created a scission inside the Fourth International after World War II. The group founded a review Socialisme ou Barbarie that criticized Marxism and the Trotskyist interpretation of the status of the USSR. The rigorous description of this review reveals the mixture of strong theoretical views on bureaucratic societies and empirical investigations of reactions against those societies. The hypothesis is that this group failed to be a new political force. As a matter of fact, is it possible to depict the evolution of Socialisme ou Barbarie as an investigative journalism based on a strong political and philosophical theory? Keywords: Bureaucratic societies, Sovietologist, investigative journalism, Socialisme ou Barbarie, Castoriadis, political periodicals Introduction The review Socialisme ou Barbarie is a political act refusing the Trotskyist interpretation of the USSR regime as a degenerated worker State. It comes from an ideological scission inside the Fourth International and was cofounded by the Greek exilé Cornelius Castoriadis and Claude Lefort. It is characterized by an early understanding of the nature of the USSR. Socialisme ou Barbarie is first a tendency inside the Fourth International before being a review and a real revolutionary group. The review existed from 1948 until 1965 whereas the group Socialisme ou Barbarie continued to exist until 1967. -

The Internationale Words by Eugene Pottier (Paris 1871) Music by Pierre Degeyter (1888)

The Internationale Words by Eugene Pottier (Paris 1871) Music by Pierre Degeyter (1888) Arise ye workers from your slumbers Arise ye prisoners of want For reason in revolt now thunders And at last ends the age of cant. Away with all your superstitions Servile masses arise, arise We'll change henceforth the old tradition And spurn the dust to win the prize. So comrades, come rally And the last fight let us face The Internationale unites the human race. So comrades, come rally And the last fight let us face The Internationale unites the human race. No more deluded by reaction On tyrants only we'll make war The soldiers too will take strike action They'll break ranks and fight no more And if those cannibals keep trying To sacrifice us to their pride They soon shall hear the bullets flying We'll shoot the generals on our own side. No saviour from on high delivers No faith have we in prince or peer Our own right hand the chains must shiver Chains of hatred, greed and fear E'er the thieves will out with their booty And give to all a happier lot. Each at the forge must do their duty And we'll strike while the iron is hot. National Anthem of the Soviet Union The 1943 English version, as recorded by Paul Robeson goes as follows: United forever in friendship and labor Our mighty republics will ever endure The great Soviet Union will live through the ages; The dream of a people, their fortress secure REFRAIN: Long live our Soviet motherland Built by the people's mighty hand Long live our people, united and free Strong in our friendship, tried by fire Long may our crimson flag inspire Shining in glory, for all men to see Through days dark and stormy, while great Lenin led us Our eyes saw the bright sun of freedom of all And Stalin, our leader, with faith in the people Inspired us to build up a land that we love (refrain) We fought for the future, destroyed the invader And brought to our homeland the laurels of fame A glory will live in the memory of nations And all generations will honor her name (refrain). -

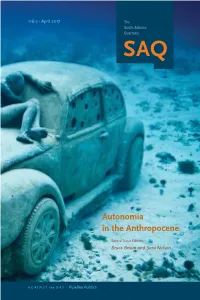

Autonomia in the Anthropocene

SAQ 116:2 • April 2017 The South Atlantic Autonomia in the Anthropocene Quarterly Bruce Braun and Sara Nelson, Special Issue Editors Autonomia in the Anthropocene: SAQ New Challenges to Radical Politics Sara Nelson and Bruce Braun Species, Nature, and the Politics of the Common: 116:2 From Virno to Simondon Miriam Tola • April Anthropocene and Anthropogenesis: Philosophical Anthropology 2017 and the Ends of Man Jason Read At the Limits of Species Being: Anthropocene Autonomia and the Sensing the Anthropocene Elizabeth R. Johnson The Ends of Humans: Anthropocene, Autonomism, Antagonism, and the Illusions of our Epoch Elizabeth A. Povinelli The Automaton of the Anthropocene: On Carbosilicon Machines and Cyberfossil Capital Matteo Pasquinelli Intermittent Grids Karen Pinkus Autonomia Anthropocene: Cover: Anthropocene, Victims, Narrators, and Revolutionaries underwater sculpture, Marco Armiero and Massimo De Angelis depth 8m, MUSA Collection, in the Anthropocene Cancun/Isla Mujeres, Mexico. Special Issue Editors Refusing the World: © Jason deCaires Taylor. Silence, Commoning, All rights reserved, Bruce Braun and Sara Nelson and the Anthropocene DACS / ARS 2017 Anja Kanngieser and Nicholas Beuret Autonomy and the Intrusion of Gaia Duke Isabelle Stengers AGAINST the DAY • Pipeline Politics Editor Michael Hardt Editorial Board Srinivas Aravamudan Rey Chow Roberto M. Dainotto Fredric Jameson Ranjana Khanna The South Atlantic Wahneema Lubiano Quarterly was founded in 1901 by Walter D. Mignolo John Spencer Bassett. Kenneth Surin Kathi Weeks Robyn -

End of Work, Complete Automation, Robotic Anarcho-Communism

It’s the End of Work as We Know It: End Of Work, Complete Automation, Robotic Anarcho-Communism Pierpaolo Marrone † [email protected] ABSTRACT In this article I explore some consequences of the relations between technique, capitalism and radical liberation ideologies (such as communism and anarcho- communism). My thesis is that the latter are going to rise to the extent that wage labor will become a scarce commodity. Through total automation, however, what may occur will not be the end of the reign of scarcity, but a new oppressive order. It is sometimes said that the end of the so-called ethical parties in the West was the consequence of the end of ideologies (Lepre, 2006). The alleged end of ideologies (Fukuyama, 2003) would have produced two relevant consequences: 1) the decline of politics, replaced by the economy; 2) the end of any utopian inspiration, which would have been rendered impossible by the dominance of the technique, since this would represent the universal affirmation of instrumental rationality (the one that Weber called "steel cage"; Weber, 1971). It is, in any case, a fact that ethical parties, which proposed complex alternative visions of the world, have disappeared, perhaps because they corresponded to a Fordist work organization, based on production and not consumption (Boltanski & Chiapello, 1999) . It is not at all obvious, however, that the end of ideologies really did exist. Just as it is not obvious - and it will be the thesis that I will try to explore in this paper - that the spirit of utopia cannot rise again and perhaps it has never gone away, together with its hopes and its dangers.