Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real Democracy in the Occupy Movement

NO STABLE GROUND: REAL DEMOCRACY IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT ANNA SZOLUCHA PhD Thesis Department of Sociology, Maynooth University November 2014 Head of Department: Prof. Mary Corcoran Supervisor: Dr Laurence Cox Rodzicom To my Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is an outcome of many joyous and creative (sometimes also puzzling) encounters that I shared with the participants of Occupy in Ireland and the San Francisco Bay Area. I am truly indebted to you for your unending generosity, ingenuity and determination; for taking the risks (for many of us, yet again) and continuing to fight and create. It is your voices and experiences that are central to me in these pages and I hope that you will find here something that touches a part of you, not in a nostalgic way, but as an impulse to act. First and foremost, I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Laurence Cox, whose unfaltering encouragement, assistance, advice and expert knowledge were invaluable for the successful completion of this research. He was always an enormously responsive and generous mentor and his critique helped sharpen this thesis in many ways. Thank you for being supportive also in so many other areas and for ushering me in to the complex world of activist research. I am also grateful to Eddie Yuen who helped me find my way around Oakland and introduced me to many Occupy participants – your help was priceless and I really enjoyed meeting you. I wanted to thank Prof. Szymon Wróbel for debates about philosophy and conversations about life as well as for his continuing support. -

Eui Working Papers

Repository. Research Institute University UR P 20 European Institute. Cadmus, % European University Institute, Florence on University Access European EUI Working Paper SPS No. 94/16 Open Another Revolution The PDS inItaly’s Transition SOCIALSCIENCES WORKING IN POLITICALIN AND PAPERS EUI Author(s). Available M artin 1989-1994 The 2020. © in J. B ull Manqué Library EUI ? ? the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European Institute. Cadmus, on University Access European Open Author(s). Available The 2020. © in Library EUI the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European Institute. EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE Cadmus, DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL AND AND DEPARTMENTSOCIAL OF POLITICAL SCIENCES on BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) University Access EUI EUI Working Paper SPS No. 94/16 The PDS in Italy’s Transition Departmentof Politics A Contemporary History Another Revolution European Open Department ofPolitical and Social Sciences European University Institute (1992-93) rodEuropean Studies Research Institute M Universityof Salford Author(s). Available artin 1989-1994 The and 2020. © J. J. in bull M anquil Library EUI the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European Institute. Cadmus, on University Access No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form European Open Printed in Italy in December 1994 without permission of the author. I I - 50016 San Domenico (FI) European University Institute Author(s). Available The All rights reserved. 2020. © © Martin J. Bull Badia Fiesolana in Italy Library EUI the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European paper will appear in a book edited by Stephen Gundle and Simon Parker, published by Routledge, and which will focus on the changes which Italianpolitics underwent in the period during the author’s period as a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the European University Institute, Florence. -

Roberto Maroni, Says That He Would Not Oppose Selling Italian Industries to Speculator 'We Want a Free Market George Soros

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 21, Number 6, February 4, 1994 establishment. It never had a popular base and is not going Segni is suspected of being a :Freemason, but nobody can to survive as a party. Its leader, Giorgio La Malfa, wants to prove it yet. He recently foundt:lda movement called Pact for join the left, but has a bad image since he was accused of Italy. He has been courted bOth by the left and by the rightto corruption. run as prime minister. He has not yet decided, though, lean Socialist Party: The PSI is the party most hit by corrup ing more toward the "moder�te" portion of the political tion scandals, and has almost disappeared from the electoral spectrum. map in recent votes. Its leader, Ottaviano Del Turco, wants Italian Force: This is the qetwork of "clubs" created by to dissolve it and join the PDS. The faction led by former media magnate Silvio Berlusc()ni. Berlusconi's TV empire Prime Minister Bettino Craxi will not follow him, and is is second in the world only ttl Ted Turner's Cable News looking for a place in the "moderate" bloc. Network; he owns three priv�te channels in Italy, one in Social Democratic Party: The PSDI has consistently France, and one in Poland. He Qwns also a supermarket chain been a member of Italy's governmentcoalitions, but today it and a construction operation. $erlusconi is not liked by the is not going to survive, and its leaders are looking for a place international financial marke�, which dropped the day he in the "moderate" bloc. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

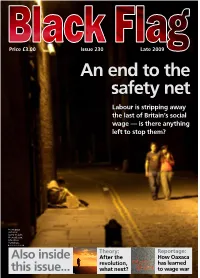

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

By Leo Sisti on July 14, 2008, at 7:30 A.M., Ottaviano Del Turco Was

by Leo Sisti On July 14, 2008, at 7:30 a.m., Ottaviano Del Turco was about to leave his home in the small village of Collelungo for a trip to L’Aquila, the capital of the Abruzzo region in southern Italy. He had been Abruzzo’s governor since 2005 after resigning from the European parliament where he was elected to the Socialist group. Just as Del Turco was getting into his car, an agent of the Guardia di Finanza appeared and handed Del Turco an arrest warrant, signed by a judge in Pescara, another Abruzzo town. The warrant placed Del Turco, 63, under arrest on charges of corruption and extortion. He was suspected of taking a bribe of 5.8 million euros (US$7 million) in exchange for his help in a financial scheme to save Vincenzo Angelini, a private clinic owner, from bankruptcy. Angelini was claiming unpaid credits of 150 million euros (US$194,000,000) from the Abruzzo region. Del Turco’s long political career makes him well-known and powerful. In 1977, at 39, he became deputy secretary general of the Socialist-Communist Trade Union CGIL (CGIL — Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro). In 1987, he challenged the late Socialist Party Leader Bettino Craxi, who was then prime minister, on “moral issues.” In 1993, a year after the “Clean Hands” investigation snagged Craxi in its net, Del Turco was given by Craxi an envelope containing the foreign account numbers of the Socialist Party. Del Turco refused to open the envelope, because he didn’t want to share any responsibility in a dangerous event linked to possible cases of bribery. -

Partito Socialista Italiano Di Fiesole È Composto Da 69 Fra Buste E Cartelle

Quaderni d’Archivio n° 2 Quaderni d’Archivio n° 2 L’Archivio del PSI di Fiesole A cura di Massimiliano Giorgi Presentazione di Fabio Incatasciato Con un saggio introduttivo di Emilio Capannelli Edizioni Polistampa © 2009 EDIZIONI POLISTAMPA Via Livorno, 8/32 - 50142 Firenze Tel. 055 737871 (15 linee) [email protected] - www.polistampa.com ISBN 978-88-596-0000-0 INDICE Presentazione di Fabio Incatasciato 9 I socialisti a Fiesole di Emilio Capannelli 11 INVENTARIO Il fondo archivistico del PSI di Fiesole 55 CARTEGGIO E ATTI 1890-1943 . 57 1944-1946 . 59 1947-1951 . 61 1952-1953 . 66 1954-1956 . 68 1957-1963 . 70 1964-1966 . 73 1967-1969 . 76 1970 . 80 1971 . 82 1972 . 84 1973 . 87 1973 . 90 1974 . 91 1974 . 93 1975 . 94 1975 . 97 1976 . 98 1976 . 102 6 INDICE 1977 . 104 1977 . 105 1978 . 107 1978 . 107 1979 . 108 1979 . 110 1980 . 111 1980 . 112 1981 . 114 1981 . 117 1982 . 119 1982 . 122 1983 . 122 1983 . 125 1984 . 125 1984 . 127 1985 . 129 1985 . 130 1986 . 131 1986 . 132 1986-1989 . 132 1986-1989 . 133 1991-1992 . 134 1991-1992 . 136 ATTIVITÀ ELETTORALE E FESTIVAL DE «L’AVANTI!» Referendum e feste ‘Avanti’, 1974-1985 . 137 Elezioni amministrative, 15 giugno 1975 . 138 Elezioni politiche, 20 giugno 1976 . 139 Elezioni politiche, 3 giugno 1979 . 140 Elezioni amministrative, 8 giugno 1980 . 141 Elezioni politiche, 26 giugno 1983 . 142 Elezioni amministrative, 12 maggio 1985 . 143 MATERIALE DI DOCUMENTAZIONE Decentramento. Autogestione . 145 Progetto Socialista e Comm. Tributaria . 146 Piano Pluriennale di Attuazione . 146 INDICE 7 Regione Toscana, Conferenza Regionale per l’occupazione. -

Gli Anni Di Craxi

GLI ANNI DI CRAXI AA.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd 1 223/11/123/11/12 116.556.55 AA.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd 2 223/11/123/11/12 116.556.55 Il crollo Il PSI nella crisi della prima Repubblica a cura di Gennaro Acquaviva e Luigi Covatta Marsilio AA.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd 3 223/11/123/11/12 116.556.55 © 2012 by Marsilio Editori® s.p.a. in Venezia Prima edizione: novembre 2012 ISBN 978-88-317-1415 www.marsilioeditori.it Realizzazione editoriale: in.pagina s.r.l., Venezia-Mestre AA.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd 4 223/11/123/11/12 116.556.55 INDICE 9 Nota di Gennaro Acquaviva 11 Introduzione di Gennaro Acquaviva e Luigi Covatta parte i la dissoluzione del gruppo dirigente del psi 19 Nota metodologica di Livio Karrer, Alessandro Marucci e Luigi Scoppola Iacopini interviste 27 Carlo Tognoli 61 Giorgio Benvenuto 99 Giulio Di Donato 141 Giuseppe La Ganga 187 Salvo Andò 229 Claudio Signorile 269 Claudio Martelli 321 Gianni De Michelis 5 AA.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd.Craxi_Crollo_parte.1.indd 5 223/11/123/11/12 116.556.55 indice 361 Ugo Intini 393 Carmelo Conte 429 Valdo Spini 465 Rino Formica 487 Giuliano Amato 521 Luigi Covatta 547 Fabio Fabbri 573 Fabrizio Cicchitto 615 Gennaro Acquaviva 653 Cenni biografi ci degli intervistati parte ii il psi nella crisi della prima repubblica 661 L’irresistibile ascesa e la drammatica caduta di Bettino Craxi di Piero Craveri 685 Il psi, Craxi e la politica estera italiana di Ennio Di Nolfo 713 Il caso Giustizia: -

Bowie, Thomas D

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Labor Series THOMAS D. BOWIE Interviewer: James F. Shea Initial interview date: February 25, 1994 Co yright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Bac ground Born in Minnesota Carleton College Studies in France Studies in the Hague Marriage Family Foreign language study Interest in the Foreign Service Foreign Service view of Labor Attach&s Entered the Foreign Service in 1945 Posts of Assignment Department of Commerce, -orld Trade Intelligence Department of State. /unior Economic Analyst 194011942 Blac listing recommendations Madrid, Spain3 Economic Officer 194211945 Ambassador Carlton /oseph Huntley Hayes Franco Spain Economic warfare Marseille, France 194511947 Rabat. Morocco 194711949 Arab1Israeli -ar American1protected Moroccan /ew Arab problems 1 -arsaw, Poland3 194911951 -ar destruction Environment Milan, Italy3 Labor7Political Officer 195111954 8S Ambassadors Irving Brown Colonel Lane Henry T. Rowell Beniamino 9igli Labor reporting Office Memorandum :OM) Reduction in Force :1952) McCarthyism —Offshore Procurement“ C9IL :Communist1dominated Trade 8nion) 8S policy effect on Italian labor Ambassador Luce Paul Tenney Eldridge Durbrow Sesto San 9iovanni communists Labor developments in Northern Italy Milan 8SIS Office Anti1American demonstrations Labor conditions -age Integration Fund Socialist7Communist relationship Christian Democratic Party AFL1CIO 9eorge Meany Italian Trade 8nions Tom Lane Comments on Socialist Movement Italian Labor Leaders Personal reception -

Fire and Flames

FIRE AND FLAMES FIRE AND FLAMES a history of the german autonomist movement written by Geronimo introduction by George Katsiaficas translation and afterword by Gabriel Kuhn FIRE AND FLAMES: A History of the German Autonomist Movement c. 2012 the respective contributors. This edition c. 2012 PM Press Originally published in Germany as: Geronimo. Feuer und Flamme. Zur Geschichte der Autonomen. Berlin/Amsterdam: Edition ID-Archiv, 1990. This translation is based on the fourth and final, slightly revised edition of 1995. ISBN: 978-1-60486-097-9 LCCN: 2010916482 Cover and interior design by Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org Images provided by HKS 13 (http://plakat.nadir.org) and other German archives. PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the USA on recycled paper by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, MI. www.thomsonshore.com CONTENTS Introduction 1 Translator’s Note and Glossary 9 Preface to the English-Language Edition 13 Background 17 ------- I. THE EMERGENCE OF AUTONOMOUS POLITICS IN WEST GERMANY 23 A Taste of Revolution: 1968 25 The Student Revolt 26 The Student Revolt and the Extraparliamentary Opposition 28 The Politics of the SDS 34 The Demise of the SDS 35 Militant Grassroots Currents 37 What Did ’68 Mean? 38 La sola soluzione la rivoluzione: Italy’s Autonomia Movement 39 What Happened in Italy in the 1960s? 39 From Marxism to Operaismo 40 From Operaio Massa to Operaio Sociale 42 The Autonomia Movement of 1977 43 Left Radicalism in the 1970s 47 “We Want Everything!”: Grassroots Organizing in the Factories 48 The Housing Struggles 52 The Sponti Movement at the Universities 58 A Short History of the K-Groups 59 The Alternative Movement 61 The Journal Autonomie 63 The Urban Guerrilla and Other Armed Groups 66 The German Autumn of 1977 69 A Journey to TUNIX 71 II. -

CHAPTER I – Bloody Saturday………………………………………………………………

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF JOURNALISM ITALIAN WHITE-COLLAR CRIME IN THE GLOBALIZATION ERA RICCARDO M. GHIA Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Journalism with honors in Journalism Reviewed and approved by Russell Frank Associate Professor Honors Adviser Thesis Supervisor Russ Eshleman Senior Lecturer Second Faculty Reader ABSTRACT At the beginning of the 2000s, three factories in Asti, a small Italian town, went broke and closed in quick succession. Hundreds of men were laid off. After some time, an investigation mounted by local prosecutors began to reveal what led to bankruptcy. A group of Italian and Spanish entrepreneurs organized a scheme to fraudulently bankrupt their own factories. Globalization made production more profitable where manpower and machinery are cheaper. A well-planned fraudulent bankruptcy would kill three birds with one stone: disposing of non- competitive facilities, fleecing creditors and sidestepping Italian labor laws. These managers hired a former labor union leader, Silvano Sordi, who is also a notorious “fixer.” According to the prosecutors, Sordi bribed prominent labor union leaders of the CGIL (Italian General Confederation of Labor), the major Italian labor union. My investigation shows that smaller, local scandals were part of a larger scheme that led to the divestments of relevant sectors of the Italian industry. Sordi also played a key role in many shady businesses – varying from awarding bogus university degrees to toxic waste trafficking. My research unveils an expanded, loose network that highlights the multiple connections between political, economic and criminal forces in the Italian system. -

What Remains of the Italian Left of the 1970S? Jonathan Mullins

What Remains of the Italian Left of the 1970s? Jonathan Mullins Suddenly a photograph reaches me; it animates me and I animate it. So that is how I must name the attraction which makes it exist: an animation. The photograph itself is in no way animated (I do not believe in ‘life-like’ photographs), but it animates me: this is what creates every adventure. —Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida1 In September 1977, 20,000 young leftists descended upon Bologna for a convention at the Palasport stadium. The convention is largely identified with the end of the movement of 1977, in which youth on the far left broke with the Italian Communist Party (PCI), ridiculed institutional politics and the very idea of the social contract, and adopted forms of direct action. It is known for its mass protests, which usually ended in confrontations with the police in the streets, and for its broadcasts, via free radio stations, of messages of refusal that mixed aesthetic forms and political discourse. These young people had come to Bologna, the historical stronghold of the PCI, to protest the police repression of the movement, to re-vitalize collective forms of dissent and just be together. This scene was one of the last hurrahs of non-violent, collective far leftist revolt of 1970s Italy. It was captured in forty- nine minutes of unedited 16mm footage by the commercial production company Unitelefilm that is held at the Audio-Visual Archive for Democratic and Labor Movements (AAMOD) in Rome.2 The footage is remarkable for its recording of what happened on the margins of the Palasport convention and not the convention itself; the viewer never sees any of the orations, banners or charged publics that gathered at the Palasport stadium where the convention took place. -

Giugni Inventario Definitivo

I Attività Giovanile 1947-1962 1. Volume 1949 «Università di Genova. Anno Accademico 1948-1949. Dal delitto di coalizione al diritto di sciopero. Tesi di Laurea dello studente Luigi Giugni. Relatore Chiar.mo Prof. G. Vassalli. Novembre 1949». Ril. cart., pp. 1-320 (8); sottoscrizione autografa a p. 320. 2. Busta 1947-1952 Fascicoli: 1. 1947 – «International free trade union news», II, 2. 2. 1947 – «Nouvelle internationales du mouvement syndical libre», II, 3-9. 3. 1948 – «Il lavoro nuovo. Quotidiano della Federazione del Partito Socialista Italiano», IV (1948), 193. 4. 1949 – «Il Secolo XIX», 1949, 2771. 5. 1949 – «Giustizia-Justice (Italian Edition). Organo ufficiale dell’Internationale Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union», vol. XXXII, 19, Jersey City, ottobre 1949. 6. 1947-1950 – «Notiziario Internazionale del movimento sindacale libero», edizione italiana, I, 1-2 (1947); II, 1-12 (1948); IV, 3 (1950). 7. 1949-1950 – «Tesi e primi passi nell’Accademia»: 1) «Il matrimonio civile deve reputarsi valido nonostante la riserva mentale o la simulazione dei nubenti. Tesina dello studente Giugni Luigi»; 2) Ritagli di stampa; 3) Lettere di Arturo Carlo Jemolo e Rinaldo Rigola: a) Arturo Carlo Jemolo a Gino Giugni, autografa su carta intestata «Università degli Studi di Roma», Roma, 30 aprile 1949; b) Rinaldo Rigola a Gino Giugni, datt. con sottoscrizione autografa, pp. 1-2, Milano, 14 aprile 1949. c) Rinaldo Rigola a Gino Giugni, testo di altra mano, sottoscrizione autografa, Milano, 15 giugno 1950. 8. 1951 – «Corriere del Popolo», 22 aprile 1951, pp. 3-4. 9. 1951 – Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori (CISL), Statuto Confederale (Approvato al Congresso Confederale – Napoli, 11-14 novembre 1951), Roma, Tipolitografia Ceselli, 1951.