Introduction Introductory Thoughts on Anthropology and Urban Insurrection Don Kalb and Massimiliano Mollona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real Democracy in the Occupy Movement

NO STABLE GROUND: REAL DEMOCRACY IN THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT ANNA SZOLUCHA PhD Thesis Department of Sociology, Maynooth University November 2014 Head of Department: Prof. Mary Corcoran Supervisor: Dr Laurence Cox Rodzicom To my Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is an outcome of many joyous and creative (sometimes also puzzling) encounters that I shared with the participants of Occupy in Ireland and the San Francisco Bay Area. I am truly indebted to you for your unending generosity, ingenuity and determination; for taking the risks (for many of us, yet again) and continuing to fight and create. It is your voices and experiences that are central to me in these pages and I hope that you will find here something that touches a part of you, not in a nostalgic way, but as an impulse to act. First and foremost, I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Laurence Cox, whose unfaltering encouragement, assistance, advice and expert knowledge were invaluable for the successful completion of this research. He was always an enormously responsive and generous mentor and his critique helped sharpen this thesis in many ways. Thank you for being supportive also in so many other areas and for ushering me in to the complex world of activist research. I am also grateful to Eddie Yuen who helped me find my way around Oakland and introduced me to many Occupy participants – your help was priceless and I really enjoyed meeting you. I wanted to thank Prof. Szymon Wróbel for debates about philosophy and conversations about life as well as for his continuing support. -

Focaal Forums - Virtual Issue

FOCAAL FORUMS - VIRTUAL ISSUE Managing Editor: Luisa Steur, University of Copenhagen Editors: Don Kalb, Central European University and Utrecht University Christopher Krupa, University of Toronto Mathijs Pelkmans, London School of Economics Oscar Salemink, University of Copenhagen Gavin Smith, University of Toronto Oane Visser, Institute of Social Studies, The Hague A regular feature of Focaal is its Forum section. The Forum features assertive, provocative, and idiosyncratic forms of writing and publishing that do not fit the usual format or style of a research-based article in a regular anthropology journal. Forum contributions can be stand-alone pieces or come in the form of theme-focused collection or discussion. Introducing: www.FocaalBlog.com, which aims to accelerate and intensify anthropological conversations beyond what a regular academic journal can do, and to make them more widely, globally, and swiftly available. _________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Number 69: Mavericks Mavericks: Harvey, Graeber, and the reunification of anarchism and Marxism in world anthropology by Don Kalb II. Number 66: Forging the Urban Commons Transformative cities: A response to Narotzky, Collins, and Bertho by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat What kind of commons are the urban commons? by Susana Narotzky The urban public sector as commons: Response to Susser and Tonnelat by Jane Collins Urban commons and urban struggles by Alain Bertho Transformative cities: The three urban commons by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat III. Number 62: What makes our projects anthropological? Civilizational analysis for beginners by Chris Hann IV. Number 61: Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession by Jane Collins V. -

Flexible Capitalism

FLEXIBLE CAPITALISM EASA Series Published in Association with the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) Series Editor: Eeva Berglund, Helsinki University Social anthropology in Europe is growing, and the variety of work being done is expanding. This series is intended to present the best of the work produced by members of the EASA, both in monographs and in edited collections. The studies in this series describe societies, processes, and institutions around the world and are intended for both scholarly and student readership. 1. LEARNING FIELDS 13. POWER AND MAGIC IN ITALY Volume 1 Thomas Hauschild Educational Histories of European Social Anthropology 14. POLICY WORLDS Edited by Dorle Dracklé, Iain R. Edgar and Anthropology and Analysis of Contemporary Thomas K. Schippers Power Edited by Cris Shore, Susan Wright and Davide 2. LEARNING FIELDS Però Volume 2 Current Policies and Practices in European 15. HEADLINES OF NATION, SUBTEXTS Social Anthropology Education OF CLASS Edited by Dorle Dracklé and Iain R. Edgar Working Class Populism and the Return of the Repressed in Neoliberal Europe 3. GRAMMARS OF IDENTITY/ALTERITY Edited by Don Kalb and Gabor Halmai A Structural Approach Edited by Gerd Baumann and Andre Gingrich 16. ENCOUNTERS OF BODY AND SOUL IN CONTEMPORARY RELIGIOUS 4. MULTIPLE MEDICAL REALITIES PRACTICES Patients and Healers in Biomedical, Alternative Anthropological Reflections and Traditional Medicine Edited by Anna Fedele and Ruy Llera Blanes Edited by Helle Johannessen and Imre Lázár 17. CARING FOR THE ‘HOLY LAND’ 5. FRACTURING RESEMBLANCES Filipina Domestic Workers in Israel Identity and Mimetic Conflict in Melanesia and Claudia Liebelt the West Simon Harrison 18. -

A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition

A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition Edited by James G. Carrier Senior Research Associate in Anthropology, Oxford Brookes University, UK and Adjunct Professor of Anthropology, Indiana University, Bioomington, USA Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK • Northampton, MA, USA Contents List of contributors " ix Preface and acknowledgements xviii Introduction —- 1 James G. Carrier PART I ORIENTATIONS 1 KarlPolanyi 13 Barry L. Isaac 2 Anthropology, political economy and world-system theory 26 J.S. Eades 3 Political economy 41 Don Robotham 4 Decisions and choices: the rationality of economic actors 58 Sutti Ortiz 5 Provisioning 77 Susana Narotzky 6 Community and economy: economy's base 95 Stephen Gudeman PART II ELEMENTS 7 Property 111 Mark Busse \ 8 Labour 128 E. Paul Durrenberger 9 Industrial work 145 Jonathan Parry 10 Money in twentieth-century anthropology 166 Keith Hart vi A handbook of economic anthropology, second edition 11 Finance 2.0 183 Bill Maurer 12 Distribution and redistribution 202 Thomas C. Patterson 13 Consumption . 220 Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld PART III CIRCULATION 14 Ceremonial exchange: debates and comparisons 239 Andrew Strathern and Pamela J, Stewart 15 Markets: places, principles and integrations 257 Kalman Applbaum 16 s The gift and gift economy 275 Yunxiang Yan 17 One-way economic transfers 291 Robert C. Hunt PART IV INTEGRATIONS 18 Gender 307 Maila Stivens 19 Environment and economy 325 Eric Hirsch 20 Culture and economy 344 Michael Blim 21 Economy and religion 361 Simon Coleman 22 Economies of ethnicity 377 Thomas -

Anthropology, Second Edition

A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition Edited by James G. Carrier Senior Research Associate in Anthropology, Oxford Brookes University, UK and Adjunct Professor of Anthropology, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK • Northampton, MA, USA Contents List of contributors IX Preface and acknowledgements XVlll Introduction James G. Carrier PARTI ORIENTATIONS Karl Polanyi 13 Barry L. Isaac 2 Anthropology, political economy and world-system theory 26 J.S. Eades 3 Political economy 41 Don Robotham 4 Decisions and choices: the rationality of economic actors 58 Sutti Ortiz 5 Provisioning 77 Susana Narotzky 6 Community and economy: economy's base 95 Stephen Gudeman PART II ELEMENTS 7 Property 111 Mark Busse 8 Labour 128 E. Paul Durrenberger 9 Industrial work 145 Jonathan Parry 10 Money in twentieth-century anthropology 166 Keith Hart v vi A handbook ofeconomic anthropology, second edition 11 Finance 2.0 183 Bill Maurer 12 Distribution and redistribution 202 Thomas C. Patterson 13 Consumption 220 Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld PART III CIRCULATION 14 Ceremonial exchange: debates and comparisons 239 Andrew Strathem and Pamela J. Stewart 15 Markets: places, principles and integrations 257 Kalman Applhaum 16 The gift and gift economy 275 Yunxiang Yan 17 One-way economic transfers 291 Robert C. Hunt PART IV INTEGRATIONS 18 Gender 307 Maila Stivens 19 Environment and economy 325 Eric Hirsch 20 Culture and economy 344 Michael Blim 21 Economy and religion 361 Simon Coleman 22 Economies of ethnicity 377 Thomas Hylland Eriksen -

Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Report 2012

Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Report 2012 - 2013 Volume I Halle /Saale Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Report 2012 – 2013 Volume I Halle/Saale Table of Contents iii Table of Contents Structure and Organisation of the Institute 2012–2013 1 Foreword 7 Department ‘Integration and Conflict’ 9 Getting Back to the Basics 9 On Comparative Methods and Theory Building 10 Recent Developments in Theory Building 14 Identification and Marginality 15 The Empirical Dimension: reflections on the production of data, documentation, and transparency 25 Research Group: Integration and Conflict along the Upper Guinea Coast (West Africa) 27 Centre for Anthropological Studies on Central Asia (CASCA) 33 Department ‘Resilience and Transformation in Eurasia’ 39 Introduction: Hierarchies of Knowledge and the Gold Standard for Anthropology in Eurasia 40 Kinship and Social Support in China and Vietnam 46 Historical Anthropology 52 Economic Anthropology 58 Urban Anthropology 64 Traders, Markets, and the State in Vietnam (Minerva Group) 69 Department ‘Law & Anthropology’ 75 Introduction: The legacy of the Project Group Legal Pluralism 75 Four Research Priorities 76 Ongoing Research Activities at the Department 82 Legacy of the Project Group Legal Pluralism 101 Local State and Social Security in Rural Hungary, Romania, and Serbia 103 Siberian Studies Centre 105 International Max Planck Research School ‘Retaliation, Mediation, and Punishment’ (IMPRS REMEP) 115 International Max Planck Research School for the Anthropology, Archaeology and History of Eurasia (IMPRS ANARCHIE) 123 Publications 131 Index 181 Location of the Institute 186 Structure and Organisation of the Institute 1 Structure and Organisation of the Institute 2012–2013 Because questions concerning the equivalence of academic titles that are conferred by institutions of higher learning in different countries have still not been resolved completely, all academic titles have been omitted from this report. -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

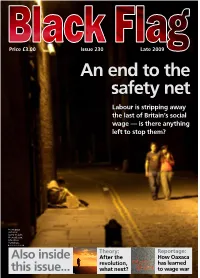

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

Anthropologies of Class: Power, Practice and Inequality Edited by James G

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-08741-5 - Anthropologies of Class: Power, Practice and Inequality Edited by James G. Carrier and Don Kalb Index More information Index A Consumer’s Republic (by L. Cohen), 90–91 Antunes, Juarez (mayor of Volta Redonda), abrazo (the hug), 158–59 158–59 absolute expediency, 128–29, 130 aristocracy of labor. See labor aristocracy accumulation by dispossession, 42–43, 44–45, Arrighi, Giovanni, 183, 184, 185 105 n 7, 150. See also primitive Arthur D. Little (consulting firm), 169, accumulation 170–71 Act 184. See Industrial Tax Exemption Act of spread of export processing zones, 176 Puerto Rico Arthur D. Little (person), 171 Adivasi assemblage and globalization, 188–89 circular migration, 124 AssociaciodeVe´ ¨ınats (residents’ association), education in Kerala, 125 111 Indian scholarly approach to, 129–30 Es Barri, 102–03, 111–12 Kottamurade, 120 changing membership, 112, 113 Adivasi identity. See also indigenism plans to improve area, 113 class analysis, 130 renewal of, 112–13 class processes, 125 autonomous practices of the self, 72, 73, ADL. See Arthur D. Little (consulting firm) 84 Aiyyappan, A., 119 Alicia’s rejecting exploitation, 86 Akathi (Kottamurade woman) ethnography describes, 74 anti-indigenism, 129 AV . See AssociaciodeVe´ ¨ınats (residents’ Muthanga land occupation association) effects of, 128–29 involvement, 127 Bajo Segura (region in Spain), 80–81 social and economic position, 126–27 exploitation in, 77 Alicia (activist in Bajo Segura), 77–79, 82, 85 mixed economy, 77 Alliance for Progress, -

HISTORICAL ANTHROPOLOGY (Frazer Lecture)1

HISTORICAL ANTHROPOLOGY (Frazer Lecture)1 By Alan Macfarlane From: Cambridge Anthropology Vol.3 no.3 (1977) Marc Bloch wrote that the "good historian is like the giant of the fairy tale. He knows that wherever he catches the scent of human flesh, there his quarry lies" (Bloch, p.26).The good anthropologist is likewise a cannibal. "What social science is properly about" urged Wright-Mills, "is the human variety, which consists of all the social worlds in which men have lived, are living, and might live" (Wright-Mills, p.147). In the first half of this paper I will discuss the ways in which social anthropology and history could, in theory, benefit each other. In the second half I will briefly describe a case study of an attempt to compare historical and contemporary societies. The current dilemma facing social anthropologists can be stated briefly. While their past achievements command considerable respect and still excite students and general readers, practitioners already regard themselves as an almost extinct species. Their plight is easily explained. Their hunting grounds have nearly vanished, the pre-literate and non-industrial societies they originally studied have almost been destroyed and their rather simple weapons, the diffusionist spear and functionalist bow, are obsolete. They do not satisfy emotionally or intellectually. Doom was prophesied in the early 1950s, but has been masked and postponed by the hitherto impenetrable musings of Levi-Strauss. Some believed that he had discovered a hidden pass into a new land, thus locating a rich flora and fauna consisting of symbols, myths, collective representations, classificatory systems, all of which could be trapped and devoured with the aid of the structuralist net. -

Introduction Headlines of Nation, Subtexts of Class: Working-Class Populism and the Return of the Repressed in Neoliberal Europe

Introduction Headlines of Nation, Subtexts of Class: Working-Class Populism and the Return of the Repressed in Neoliberal Europe Don Kalb This is a book about the emergence and spread of mostly right-wing populism in contemporary Europe. Since about 1989 neo-nationalism has grown as a volatile political force in almost all European societies. This book does not so much look at the movements, political entrepreneurs and formal ideologies, as is done by political scientists and social movement researchers. Our focus is rather on the social groups that comprise their key constituencies. In a broad sense, these are working-class people. We study them in their natural habitats – factories, offices and neighbourhoods. And we study them as they are affected by longer run processes of social change commonly associated with neoliberal globalization. This book is therefore also a book about class and class formation(s). Because of this, we also look at capital, the state and the transnational capitalist order in the making, and how these forces impact on locales and sites. We make the anthropological case that working-class neo- nationalism is the somewhat traumatic expression of material and cultural experiences of dispossession and disenfranchisement in the neoliberal epoch. We argue that such experiences cannot be so easily signified in other than nationalist ways within the new neoliberal Europe, largely because capital, the upper middle classes and political, professional and managerial elites have become ‘cosmopolitanized’ and have lost their interest in the language of class and the nationally guaranteed social rights that it entails. Their class interests do not conjoin anymore with the project of welfare-state formation. -

1 CASCA/AES 2009 Conference Organizers / Organisation Du Colloque Local Organizing Committee / Comité Local D'organisation

1 CASCA/AES 2009 Conference Organizers / Organisation du colloque Local Organizing Committee / Comité local d’organisation, University of British Columbia Chair / Président: Gastón Gordillo General administrator / Administration générale: Natasha Damiano Paterson Faculty members / Corps professoral: Carole Blackburn, Alexia Bloch, Charles Menzies, Patrick Moore Students / Étudiant(e)s: Dai Cooper, David Geary, Lina Gómez-Isaza, Arianne Loranger-Saindon, Matt Sanderson, Jayme Taylor Special thanks / Remerciements: Marie-Ève Carrier-Moisan, Solen Roth, Arianne Loranger-Saindon (for the French translations / pour les traductions de l’anglais au français), Natalie Baloy (for the caffeine supplies / pour le café), Andrew Martindale (for the website design / pour la conception du site Internet), Matt Sanderson & family, UBC Museum of Anthropology, UBC Department of Anhropology AES: Jacqueline Solway CASCA: Craig Campbell, Karli Whitmore 2 CONFERENCE VENUES / LIEUX DU COLLOQUE • Anthropology and Sociology (Anso), 6303 NW Marine Drive • Buchanan D, 1866 Main Mall • Hebb Theatre, 2045 East Mall • Museum of Anthropology (MOA), 6393 NW Marine Drive REGISTRATION / INSCRIPTION Anthropology and Sociology Lounge (CASCA/AES) Tuesday, May 12 / mardi 12 mai 3:00 pm - 7:00 pm Wednesday, May 13 / mercredi 13 mai 9:00 am - 4:00 pm Thursday, May 14 / jeudi 14 mai 8:30 am - 4:00 pm Friday, May 15 / vendredi 15 mai 8:30 am - 4:00 pm Saturday, May 16 / samedi 16 mai 8:30 am - 12:30 pm (CASCA only / CASCA seulement) CONFERENCE REFRESHMENTS / RAFRAÎCHISSEMENTS Coffee, tea, and water provided daily at Meekison Lounge (ground floor of Buchanan D) and the Anthropology and Sociology Lounge / Du café, du thé et de l’eau sont disponibles tous les jours au Meekison Lounge, au rez-de-chaussée du Buchanan D, de même que dans le salon du Département d’anthropologie CASCA/AES BOOK EXHIBIT / EXPOSITION DE LIVRES (organized by / organisée par la Library of Social Sciences). -

Fire and Flames

FIRE AND FLAMES FIRE AND FLAMES a history of the german autonomist movement written by Geronimo introduction by George Katsiaficas translation and afterword by Gabriel Kuhn FIRE AND FLAMES: A History of the German Autonomist Movement c. 2012 the respective contributors. This edition c. 2012 PM Press Originally published in Germany as: Geronimo. Feuer und Flamme. Zur Geschichte der Autonomen. Berlin/Amsterdam: Edition ID-Archiv, 1990. This translation is based on the fourth and final, slightly revised edition of 1995. ISBN: 978-1-60486-097-9 LCCN: 2010916482 Cover and interior design by Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org Images provided by HKS 13 (http://plakat.nadir.org) and other German archives. PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the USA on recycled paper by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, MI. www.thomsonshore.com CONTENTS Introduction 1 Translator’s Note and Glossary 9 Preface to the English-Language Edition 13 Background 17 ------- I. THE EMERGENCE OF AUTONOMOUS POLITICS IN WEST GERMANY 23 A Taste of Revolution: 1968 25 The Student Revolt 26 The Student Revolt and the Extraparliamentary Opposition 28 The Politics of the SDS 34 The Demise of the SDS 35 Militant Grassroots Currents 37 What Did ’68 Mean? 38 La sola soluzione la rivoluzione: Italy’s Autonomia Movement 39 What Happened in Italy in the 1960s? 39 From Marxism to Operaismo 40 From Operaio Massa to Operaio Sociale 42 The Autonomia Movement of 1977 43 Left Radicalism in the 1970s 47 “We Want Everything!”: Grassroots Organizing in the Factories 48 The Housing Struggles 52 The Sponti Movement at the Universities 58 A Short History of the K-Groups 59 The Alternative Movement 61 The Journal Autonomie 63 The Urban Guerrilla and Other Armed Groups 66 The German Autumn of 1977 69 A Journey to TUNIX 71 II.