Introduction Headlines of Nation, Subtexts of Class: Working-Class Populism and the Return of the Repressed in Neoliberal Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focaal Forums - Virtual Issue

FOCAAL FORUMS - VIRTUAL ISSUE Managing Editor: Luisa Steur, University of Copenhagen Editors: Don Kalb, Central European University and Utrecht University Christopher Krupa, University of Toronto Mathijs Pelkmans, London School of Economics Oscar Salemink, University of Copenhagen Gavin Smith, University of Toronto Oane Visser, Institute of Social Studies, The Hague A regular feature of Focaal is its Forum section. The Forum features assertive, provocative, and idiosyncratic forms of writing and publishing that do not fit the usual format or style of a research-based article in a regular anthropology journal. Forum contributions can be stand-alone pieces or come in the form of theme-focused collection or discussion. Introducing: www.FocaalBlog.com, which aims to accelerate and intensify anthropological conversations beyond what a regular academic journal can do, and to make them more widely, globally, and swiftly available. _________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Number 69: Mavericks Mavericks: Harvey, Graeber, and the reunification of anarchism and Marxism in world anthropology by Don Kalb II. Number 66: Forging the Urban Commons Transformative cities: A response to Narotzky, Collins, and Bertho by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat What kind of commons are the urban commons? by Susana Narotzky The urban public sector as commons: Response to Susser and Tonnelat by Jane Collins Urban commons and urban struggles by Alain Bertho Transformative cities: The three urban commons by Ida Susser and Stéphane Tonnelat III. Number 62: What makes our projects anthropological? Civilizational analysis for beginners by Chris Hann IV. Number 61: Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession Wal-Mart, American consumer citizenship, and the 2008 recession by Jane Collins V. -

Flexible Capitalism

FLEXIBLE CAPITALISM EASA Series Published in Association with the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) Series Editor: Eeva Berglund, Helsinki University Social anthropology in Europe is growing, and the variety of work being done is expanding. This series is intended to present the best of the work produced by members of the EASA, both in monographs and in edited collections. The studies in this series describe societies, processes, and institutions around the world and are intended for both scholarly and student readership. 1. LEARNING FIELDS 13. POWER AND MAGIC IN ITALY Volume 1 Thomas Hauschild Educational Histories of European Social Anthropology 14. POLICY WORLDS Edited by Dorle Dracklé, Iain R. Edgar and Anthropology and Analysis of Contemporary Thomas K. Schippers Power Edited by Cris Shore, Susan Wright and Davide 2. LEARNING FIELDS Però Volume 2 Current Policies and Practices in European 15. HEADLINES OF NATION, SUBTEXTS Social Anthropology Education OF CLASS Edited by Dorle Dracklé and Iain R. Edgar Working Class Populism and the Return of the Repressed in Neoliberal Europe 3. GRAMMARS OF IDENTITY/ALTERITY Edited by Don Kalb and Gabor Halmai A Structural Approach Edited by Gerd Baumann and Andre Gingrich 16. ENCOUNTERS OF BODY AND SOUL IN CONTEMPORARY RELIGIOUS 4. MULTIPLE MEDICAL REALITIES PRACTICES Patients and Healers in Biomedical, Alternative Anthropological Reflections and Traditional Medicine Edited by Anna Fedele and Ruy Llera Blanes Edited by Helle Johannessen and Imre Lázár 17. CARING FOR THE ‘HOLY LAND’ 5. FRACTURING RESEMBLANCES Filipina Domestic Workers in Israel Identity and Mimetic Conflict in Melanesia and Claudia Liebelt the West Simon Harrison 18. -

A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition

A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition Edited by James G. Carrier Senior Research Associate in Anthropology, Oxford Brookes University, UK and Adjunct Professor of Anthropology, Indiana University, Bioomington, USA Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK • Northampton, MA, USA Contents List of contributors " ix Preface and acknowledgements xviii Introduction —- 1 James G. Carrier PART I ORIENTATIONS 1 KarlPolanyi 13 Barry L. Isaac 2 Anthropology, political economy and world-system theory 26 J.S. Eades 3 Political economy 41 Don Robotham 4 Decisions and choices: the rationality of economic actors 58 Sutti Ortiz 5 Provisioning 77 Susana Narotzky 6 Community and economy: economy's base 95 Stephen Gudeman PART II ELEMENTS 7 Property 111 Mark Busse \ 8 Labour 128 E. Paul Durrenberger 9 Industrial work 145 Jonathan Parry 10 Money in twentieth-century anthropology 166 Keith Hart vi A handbook of economic anthropology, second edition 11 Finance 2.0 183 Bill Maurer 12 Distribution and redistribution 202 Thomas C. Patterson 13 Consumption . 220 Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld PART III CIRCULATION 14 Ceremonial exchange: debates and comparisons 239 Andrew Strathern and Pamela J, Stewart 15 Markets: places, principles and integrations 257 Kalman Applbaum 16 s The gift and gift economy 275 Yunxiang Yan 17 One-way economic transfers 291 Robert C. Hunt PART IV INTEGRATIONS 18 Gender 307 Maila Stivens 19 Environment and economy 325 Eric Hirsch 20 Culture and economy 344 Michael Blim 21 Economy and religion 361 Simon Coleman 22 Economies of ethnicity 377 Thomas -

Anthropology, Second Edition

A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition Edited by James G. Carrier Senior Research Associate in Anthropology, Oxford Brookes University, UK and Adjunct Professor of Anthropology, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK • Northampton, MA, USA Contents List of contributors IX Preface and acknowledgements XVlll Introduction James G. Carrier PARTI ORIENTATIONS Karl Polanyi 13 Barry L. Isaac 2 Anthropology, political economy and world-system theory 26 J.S. Eades 3 Political economy 41 Don Robotham 4 Decisions and choices: the rationality of economic actors 58 Sutti Ortiz 5 Provisioning 77 Susana Narotzky 6 Community and economy: economy's base 95 Stephen Gudeman PART II ELEMENTS 7 Property 111 Mark Busse 8 Labour 128 E. Paul Durrenberger 9 Industrial work 145 Jonathan Parry 10 Money in twentieth-century anthropology 166 Keith Hart v vi A handbook ofeconomic anthropology, second edition 11 Finance 2.0 183 Bill Maurer 12 Distribution and redistribution 202 Thomas C. Patterson 13 Consumption 220 Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld PART III CIRCULATION 14 Ceremonial exchange: debates and comparisons 239 Andrew Strathem and Pamela J. Stewart 15 Markets: places, principles and integrations 257 Kalman Applhaum 16 The gift and gift economy 275 Yunxiang Yan 17 One-way economic transfers 291 Robert C. Hunt PART IV INTEGRATIONS 18 Gender 307 Maila Stivens 19 Environment and economy 325 Eric Hirsch 20 Culture and economy 344 Michael Blim 21 Economy and religion 361 Simon Coleman 22 Economies of ethnicity 377 Thomas Hylland Eriksen -

Anthropologies of Class: Power, Practice and Inequality Edited by James G

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-08741-5 - Anthropologies of Class: Power, Practice and Inequality Edited by James G. Carrier and Don Kalb Index More information Index A Consumer’s Republic (by L. Cohen), 90–91 Antunes, Juarez (mayor of Volta Redonda), abrazo (the hug), 158–59 158–59 absolute expediency, 128–29, 130 aristocracy of labor. See labor aristocracy accumulation by dispossession, 42–43, 44–45, Arrighi, Giovanni, 183, 184, 185 105 n 7, 150. See also primitive Arthur D. Little (consulting firm), 169, accumulation 170–71 Act 184. See Industrial Tax Exemption Act of spread of export processing zones, 176 Puerto Rico Arthur D. Little (person), 171 Adivasi assemblage and globalization, 188–89 circular migration, 124 AssociaciodeVe´ ¨ınats (residents’ association), education in Kerala, 125 111 Indian scholarly approach to, 129–30 Es Barri, 102–03, 111–12 Kottamurade, 120 changing membership, 112, 113 Adivasi identity. See also indigenism plans to improve area, 113 class analysis, 130 renewal of, 112–13 class processes, 125 autonomous practices of the self, 72, 73, ADL. See Arthur D. Little (consulting firm) 84 Aiyyappan, A., 119 Alicia’s rejecting exploitation, 86 Akathi (Kottamurade woman) ethnography describes, 74 anti-indigenism, 129 AV . See AssociaciodeVe´ ¨ınats (residents’ Muthanga land occupation association) effects of, 128–29 involvement, 127 Bajo Segura (region in Spain), 80–81 social and economic position, 126–27 exploitation in, 77 Alicia (activist in Bajo Segura), 77–79, 82, 85 mixed economy, 77 Alliance for Progress, -

1 CASCA/AES 2009 Conference Organizers / Organisation Du Colloque Local Organizing Committee / Comité Local D'organisation

1 CASCA/AES 2009 Conference Organizers / Organisation du colloque Local Organizing Committee / Comité local d’organisation, University of British Columbia Chair / Président: Gastón Gordillo General administrator / Administration générale: Natasha Damiano Paterson Faculty members / Corps professoral: Carole Blackburn, Alexia Bloch, Charles Menzies, Patrick Moore Students / Étudiant(e)s: Dai Cooper, David Geary, Lina Gómez-Isaza, Arianne Loranger-Saindon, Matt Sanderson, Jayme Taylor Special thanks / Remerciements: Marie-Ève Carrier-Moisan, Solen Roth, Arianne Loranger-Saindon (for the French translations / pour les traductions de l’anglais au français), Natalie Baloy (for the caffeine supplies / pour le café), Andrew Martindale (for the website design / pour la conception du site Internet), Matt Sanderson & family, UBC Museum of Anthropology, UBC Department of Anhropology AES: Jacqueline Solway CASCA: Craig Campbell, Karli Whitmore 2 CONFERENCE VENUES / LIEUX DU COLLOQUE • Anthropology and Sociology (Anso), 6303 NW Marine Drive • Buchanan D, 1866 Main Mall • Hebb Theatre, 2045 East Mall • Museum of Anthropology (MOA), 6393 NW Marine Drive REGISTRATION / INSCRIPTION Anthropology and Sociology Lounge (CASCA/AES) Tuesday, May 12 / mardi 12 mai 3:00 pm - 7:00 pm Wednesday, May 13 / mercredi 13 mai 9:00 am - 4:00 pm Thursday, May 14 / jeudi 14 mai 8:30 am - 4:00 pm Friday, May 15 / vendredi 15 mai 8:30 am - 4:00 pm Saturday, May 16 / samedi 16 mai 8:30 am - 12:30 pm (CASCA only / CASCA seulement) CONFERENCE REFRESHMENTS / RAFRAÎCHISSEMENTS Coffee, tea, and water provided daily at Meekison Lounge (ground floor of Buchanan D) and the Anthropology and Sociology Lounge / Du café, du thé et de l’eau sont disponibles tous les jours au Meekison Lounge, au rez-de-chaussée du Buchanan D, de même que dans le salon du Département d’anthropologie CASCA/AES BOOK EXHIBIT / EXPOSITION DE LIVRES (organized by / organisée par la Library of Social Sciences). -

The Anthropology of Development and Globalization Final Proof 15.10.2004 12:07Pm Page I

Edelman/The Anthropology of Development and Globalization Final Proof 15.10.2004 12:07pm page i The Anthropology of Development and Globalization Edelman/The Anthropology of Development and Globalization Final Proof 15.10.2004 12:07pm page ii Blackwell Anthologies in Social and Cultural Anthropology Series Editor: Parker Shipton, Boston University Series Advisory Editorial Board: Fredrik Barth, University of Oslo and Boston University Stephen Gudeman, University of Minnesota Jane Guyer, Northwestern University Caroline Humphrey, University of Cambridge Tim Ingold, University of Aberdeen Emily Martin, Princeton University John Middleton, Yale Emeritus Sally Falk Moore, Harvard Emerita Marshall Sahlins, University of Chicago Emeritus Joan Vincent, Columbia University and Barnard College Emerita Drawing from some of the most significant scholarly work of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Blackwell Anthologies in Social and Cultural Anthropology series offers a comprehensive and unique perspective on the ever-changing field of anthropology. It represents both a collection of classic readers and an exciting challenge to the norms that have shaped this discipline over the past century. Each edited volume is devoted to a traditional subdiscipline of the field such as the anthropology of religion, linguistic anthropology, or medical anthropology; and provides a foundation in the canonical readings of the selected area. Aware that such subdisciplinary definitions are still widely recognized and useful – but increasingly problematic – these volumes are crafted to include a rare and invaluable perspective on social and cultural anthropology at the onset of the twenty-first century. Each text provides a selection of classic readings together with contemporary works that underscore the artificiality of subdisciplinary definitions and point students, researchers, and general readers in the new directions in which anthropology is moving. -

Post-Socialist Contradictions the Social Question in Central and Eastern Europe and the Making of the Illiberal Right

12 Post-Socialist Contradictions The Social Question in Central and Eastern Europe and the Making of the Illiberal Right Don Kalb Jan Breman and Marcel van der Linden have provocatively claimed that the Global South is coming to the North, rather than the other way around.1 Not “develop- ment” toward Northern modernity, but the informalization and flexibilization of the North, as in the South. They see the global economic agenda as hijacked by capitalist interests that seek the precariatization and stepped-up exploitation of the world’s laboring populations. Global agencies duplicitously present this agenda as one of employment generation and poverty reduction—and therefore represent- ing the “general interest.” “Rigidities” stemming from the old language of labor cannot be allowed to derail this. The language of labor is a particularist trick on behalf of “rent seekers,” “insiders,” and “oligopolies of labor.” The rhetoric of global institutions has perhaps been changing slightly since the financial crises of 2008– 2014. Global economic technocrats consider social inequality now evidently as a negative. But the demand for “structural adjustment” and all that it entails in terms of precariatization and the flexibility of labor remains pervasive, from the IMF to the OECD to the ECB. And then there are “the markets” with their imperious judgments and their rejection of inflation. There is no reason to believe that a new era has arrived. But as they are making this claim, Breman and van der Linden are sharply aware of differences and differentiations worldwide. There is no implication of global homogenization around a zero point of social dumping. -

Anthropologies of Modernity

Capitalism and Modernity: Institutions, Power, Agency Don Kalb Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology AY 2016/17 MA and PHD level 4 credits, 8 ECTS credits A critical approach to modernity starts with blurring the conventional liberal ‘trias’ of state, market and civil society, foundational notions of differentiation upon which the modern disciplines of economics, political science and sociology are built. These notions have been seen as basic recipes for modern rule and Western power, among others because they take the jumbo relational processes of capitalism and empire, and therewith of combined and uneven development and ongoing ‘primitive accumulation’, from view. Critical anthropological practice is aimed at complicating these modern notions of liberal order, in particular the relational dynamics of power and counter-power. They call for searching the interstices between apparently distinct institutions, and for situating actual economic, political and civic practices in real human communities in time and space in the context of unfolding combined and uneven development. This four-credit course is an advanced conversation around aspects of a broadly conceived anthropological political economy, based in short but serious digressions into ‘the transition debate’, World Systems Theory, Postcolonial critique and the critique of postcoloniality, as well as the Anthropology of Global Systems, contemporary urban Marxism, and Polanyi. The course aims at an understanding of modernity from an anthropological perspective that rejects the separation of symbolic systems on the one hand and material structures and practices on the other, and envisions situated social practice within identifiable power fields that are constituted within the ‘critical junctions’ between relevant scales from the local to the global within uneven and combined capitalist development. -

Chapter 8. Redistribution and Indebtedness

8 ° Redistribution and Indebtedness A Tale of Two Settings Deborah James This chapter builds a comparative picture of the interrelation of redistribu- tion and financialized debt in two different national contexts. It does so not by adding to the already voluminous literature written from a neo-Marxist or anarchic anticapitalist perspective, nor by endorsing the position of free-market fundamentalists, but by exploring a kind of middle ground between them. This is the arena where a “mixed economy,” long preva- lent in the funding and administering of welfare (Cunningham 1998), has become even more dominant in recent times; where we find a “pluralist hybrid of market, non-market (e.g., redistribution by the welfare state) and non-monetary (based on reciprocity) forms of economy” (Alexander 2010). Animated by the work of authors who have explored the “ethics of care” (Fraser 2014; Lawson 2007), and the complex ways in which these inform the “new public good” (Bear and Mathur 2015), I seek to chal- lenge deterministic accounts of the ways in which financialized capital- ism is experienced by those on its margins. These suggest, inter alia, that capitalism in its newest form ceaselessly seeks out new zones for profit (Lapavitsas 2013), now including those at the bottom of the pyramid; that capitalist accumulation is further facilitated in this process (Harvey 2003); and that democratic/civil options have dissolved as subjects and are recon- figured in the form of a new and more insidious type of homo economicus (Brown 2015). My account takes two very different settings, one from the global North (austerity Britain) and the other from the global South (post-democracy South Africa), and illustrates both commonalities and contrasts between them. -

Anthropologists Approach the New Capitalism

FORUM ANTHROPOLOGISTS APPROACH THE NEW CAPITALISM CLASS, LABOUR, SOCIAL REPRODUCTION: TOWARDS A NON-SELF LIMITING ANTHROPOLOGY • DON KALB • Is there any serious dispute these days that we are living through the most jumbo laying out of capitalist social relations across the globe that humanity has ever experienced? The globalization of the capitalist value regime might not yet be complete, nor function fully synchronized in real time, but it is certainly more encompassing than it has ever been. For a while the (Western) social sciences thought that they could account for this process in terms of ‘modernity at large’ or cultural globalization theory. Increasingly, though, the capitalist nature of it all, left unspecified in such visions, has pushed itself to the foreground. Even the scholars of assemblages, governmentalities, or ontology, now sometimes admit that these were capital-driven assemblages, governmentalities, and ontologies after all. That capitalist nature is not just about the aggravating turbulence of boom and bust and about the increasing financialization and securitization of the process, though these are certainly very substantial and increasingly paramount properties, taking whole societies and classes hostage to bumpy rides and exposing them to serious risks. It is also about the systematic spatial unevenness of it all, the profound social and cultural polarizations, the aggravating inequalities, the exploitation and extraction, dispossessions and enclosures; the political crises, the cracking legitimacy of the state, the elevation of the nation as an imaginary protective shield; the violence, the people on the move—and ultimately also about their drowning in the Mediterranean by the thousands as an enforced sacrifice for the scares and uncertainties of the Western middle classes unpleasantly confronted by the change of the global scenery. -

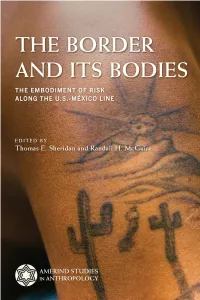

THE BORDER and ITS BODIES AMERIND STUDIES in ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editor, Christine R

THE BORDER AND ITS BODIES AMERIND STUDIES IN ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editor, Christine R. Szuter with special assistance from Joe Wilder and the Southwest Center of the University of Arizona AMERIND STUDIES IN ANTHROPOLOGY THE BORDER AND ITS BODIES THE EMBODIMENT OF RISK ALONG THE U.S.- MÉXICO LINE EDITED BY Thomas E. Sheridan and Randall H. McGuire e University of Arizona Press www .uapress .arizona .edu © by e Arizona Board of Regents All rights reserved. Published ISBN- : - - - - (cloth) Cover design by Leigh McDonald Publication of this book is made possible in part by the proceeds from a permanent endowment created with the assistance of a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Sheridan, omas E., editor. | McGuire, Randall H., editor. Title: e border and its bodies : the embodiment of risk along the U.S.- México line / edited by omas E. Sheridan and Randall H. McGuire. Other titles: Amerind studies in anthropology. Description: Tucson : e University of Arizona Press, . | Series: Amerind studies in anthropology | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Sum- mary: “is volume oers a critical investigation of the risk and the physical toll of migration along the U.S. southern border”— Provided by publisher. Identi£ers: LCCN | ISBN (cloth) Subjects: LCSH: Immigrants—Mexican- American Border Region—Social conditions. | Border crossing—Mexican- American Border Region. | Mexican- American Border Region—Emigration and immigration—Social aspects. Classi£cation: LCC JV .B | DDC ./—dc LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ Printed in the United States of America ♾ is paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z .