Notes and News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climbing the Sea Annual Report

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MARCH/APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 109 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE Annual Report 2014 PAGE 3 Climbing the Sea sailing PAGE 23 tableofcontents Mar/Apr 2015 » Volume 109 » Number 2 The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Features 3 Breakthrough The Mountaineers Annual Report 2014 23 Climbing the Sea a sailing experience 28 Sea Kayaking 23 a sport for everyone 30 National Trails Day celebrating the trails we love Columns 22 SUMMIT Savvy Guess that peak 29 MEMbER HIGHLIGHT Masako Nair 32 Nature’S WAy Western Bluebirds 34 RETRO REWIND Fred Beckey 36 PEAK FITNESS 30 Back-to-Backs Discover The Mountaineers Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the as a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of nonprofit organizations. informational meetings at each of our seven branches. Mountaineer uses: CLEAR on the cover: Lori Stamper learning to sail. Sailing story on page 23. photographer: Alan Vogt AREA 2 the mountaineer magazine mar/apr 2015 THE MOUNTAINEERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT Without individuals who appreciate the natural world and actively champion its preservation, we wouldn’t have the nearly 110 million acres of wilderness areas that we enjoy today. -

Ten Years of Winter: the Cold Decade and Environmental

TEN YEARS OF WINTER: THE COLD DECADE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE EARLY 19 TH CENTURY by MICHAEL SEAN MUNGER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Michael Sean Munger Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of History by: Matthew Dennis Chair Lindsay Braun Core Member Marsha Weisiger Core Member Mark Carey Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Michael Sean Munger iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Michael Sean Munger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History June 2017 Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century Two volcanic eruptions in 1809 and 1815 shrouded the earth in sulfur dioxide and triggered a series of weather and climate anomalies manifesting themselves between 1810 and 1819, a period that scientists have termed the “Cold Decade.” People who lived during the Cold Decade appreciated its anomalies through direct experience, and they employed a number of cognitive and analytical tools to try to construct the environmental worlds in which they lived. Environmental consciousness in the early 19 th century commonly operated on two interrelated layers. -

Hiking Withdogs

www.wta.org April 2008 » Washington Trails On Trail « Hiking withDogs Photo by “Sadie’s Driver” Dogs make some of the finest hiking companions. Sadie hikes with her “driver” on the Yellow Aster Butte Trail. Hiking with Your Best Buddy The Northwest is blessed with so many but sometimes that pushed her to the limits. places to venture in the outdoors—no matter Like the time I decided to do a trail run to the what your skill level. And, for some, it’s so top of Mount Dickerman in August. Not real much more enjoyable when you have a four- smart. She collapsed about a mile from the car legged companion to join you. The dogs I have on our way down. The combination of heat and seen on the trail seem so happy to be out roam- insufficient water took its toll. We made it back ing with their humans. fine, but I learned a lesson. Having hiked for a number of years all Some dogs are comfortable rock hopping around Washington and areas in British Colum- and scrambling, but many are not. Sadie could bia, my greatest enjoyment has been with my climb higher and faster than I could, but I al- Sadie’s buddy Sadie. This was a she-devil golden re- ways worried about what would happen when triever who, as a puppy, was a terror! But from she got to the top. Fortunately Sadie was quite Driver Sadie’s Driver lives her very first trip, being on the trail brought out confident on her feet and was cautious enough her best. -

An Appraisal of the Higher Classification of Cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadoidea) with Special Reference to the Australian Fauna

© Copyright Australian Museum, 2005 Records of the Australian Museum (2005) Vol. 57: 375–446. ISSN 0067-1975 An Appraisal of the Higher Classification of Cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadoidea) with Special Reference to the Australian Fauna M.S. MOULDS Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT. The history of cicada family classification is reviewed and the current status of all previously proposed families and subfamilies summarized. All tribal rankings associated with the Australian fauna are similarly documented. A cladistic analysis of generic relationships has been used to test the validity of currently held views on family and subfamily groupings. The analysis has been based upon an exhaustive study of nymphal and adult morphology, including both external and internal adult structures, and the first comparative study of male and female internal reproductive systems is included. Only two families are justified, the Tettigarctidae and Cicadidae. The latter are here considered to comprise three subfamilies, the Cicadinae, Cicadettinae n.stat. (= Tibicininae auct.) and the Tettigadinae (encompassing the Tibicinini, Platypediidae and Tettigadidae). Of particular note is the transfer of Tibicina Amyot, the type genus of the subfamily Tibicininae, to the subfamily Tettigadinae. The subfamily Plautillinae (containing only the genus Plautilla) is now placed at tribal rank within the Cicadinae. The subtribe Ydiellaria is raised to tribal rank. The American genus Magicicada Davis, previously of the tribe Tibicinini, now falls within the Taphurini. Three new tribes are recognized within the Australian fauna, the Tamasini n.tribe to accommodate Tamasa Distant and Parnkalla Distant, Jassopsaltriini n.tribe to accommodate Jassopsaltria Ashton and Burbungini n.tribe to accommodate Burbunga Distant. -

Early Winters.1977.1978.Pdf

Put on your Early Winters' Gore-Tex®Rainwear for . Impressive protection from wind, water and your own body's moisture! RLY It used to be that no single garment could possibly give you complete and New __ - _ comfortable protection from water, One-dollar wind, and your own body moisture. 1977-1978 Catalog But now that's all changed. The solution? Early Winters Gore-Tex Rainwear—just possibly the most versatile piece of clothing you'll ever wear. It combines the weight of a wind- breaker, the rain protection of North At- lantic foulweather gear and the breath- ability of Gore-Tex laminated fabric to keep you dry on the inside as well. Because as we proved with the now famous Light Dimensioetent (pg. 10), Gore-TelMs the one waterproof fabric that truly breathes . so not only does it keep moisture out, but it lets it out as well. (See "The Gore-Tex Story", pg. 4.) Combined with our new Gore-Tex wind and rain pants (pg. 30), you'll experience the most complete multipurpose body pro- tection ever available. Send for your Gore-Tex Parka or An- orak today, and experience the pleasure of owning and wearing one of these remark- able, lightweight garments. It's the only way to get total protection from wind, rain, and snow . without getting wet & clammy inside when you're really active. Fully guaranteed, of course! Colors: Blue/Navy; Green; Gold/Orange See pgs. 2&3 for sizes; more information. Early Winters Gore-Tex Parka No. 1211 ............................ $79.95 ppd Early Winters Gore-Tex Anorak No. -

Ed 356 932 Report No

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 356 932 RC 019 114 AUTHOR Miles, John C., Ed.; Watters, Ron, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the 1984 Conference on Outdoor Recreation: A Landmark Conference in the Outdoor Recreation Field (1st, Bozeman, Montana, November 1-4, 1984). REPORT NO ISBN-0-037834-10-6 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 213p.; Prepared by the 1984 Conference on Outdoor Recreation Steering Committee. For selected individual papers, see RC 019 115-117. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adventure Education; Disabilities; Elementary Secondary Education; *Environmental Education; Higher Education; *Leadership; *Outdoor Activities; *Outdoor Education; Program Descriptions; Program Development; Recreational Activities IDENTIFIERS *Outdoor Leadership; *Outdoor Recreation ABSTRACT This document consists of materials presented at a conference organized by representatives of university outdoor programs to discuss issues and exchange ideas about outdoor topics. Twenty-six papers were presented:(1) "Conference on Outdoor Recreation for the Disabled: Breaking the Stereotype" (Tom Whittaker and Sheila Brashear);(2) "Aquatics: A Viable Program for High Level Quadriplegics" (Jan Brabant);(3) "Community Integration with an In-house Recreation Program" (Jan Brabant);(4) "Whitewater Rafting for the Disabled" (Ginny McKay);(5) "Scuba Diving: Mainstreaming the Disabled" (Scott Taylor and Jan Brabant);(6) "Kinsmen Camp Horizon Presentation" (Bob Davies);(7) "Wilderness Leadership Certification Catch 22 Assessing the Outdoor -

Mountain Guides Association MOUNTAIN Bulletin Fall 2009 | a Publication of the American Mountain Guides Association | Amga.Com

American Mountain Guides Association MOUNTAIN bulletin Fall 2009 | A Publication of the American Mountain Guides Association | amga.com 2009 AMGA Annual Meeting laughter and holding back tears. The entire crowd rose when Doug asked those willing to stand by Main Event in Memory of Craig Luebben Silvia and Giulia as they deal with their loss to stand in support. “I laughed, I cried, it was better than Cats.” I’ve personally never seen Cats, but Margaret’s reaction to Malcolm from Trango brought with him a set of Big The Main Event – Presented by W.L. Gore – at our 2009 Annual Meeting leads me to believe that we Bros with an image of Giulia, by Jeremy Collins, put on a good show. Being a first-timer, I have nothing to compare it to, but it’s safe to say, I walked etched into them. The first set in existence. His away from the nights festivities rather humbled. The guiding community is tight. Perhaps family is a intention was to auction them to the highest better description. bidder to raise a bit of money for Giulia’s College The tension that permeated the meetings leading up to The Main Event was promptly released at Education Fund. How the auction unfolded was all the door. Greeted by a running slideshow of Craig Luebben, the discussion moved from access, at once inspiring and a bit unexpected. Opening prerequisites and membership dues to stories of Craig’s exploits and whether or not Adam Fox would bid was their retail value of $500. The bidding win the tent in the raffle for a third year in a row. -

The Mountaineers Annual Safety Report for 2013

The Mountaineers Annual Safety Report for 2013 May 11, 2014 Prepared by the Mountaineers Safety Committee: Mindy Roberts – Chair Helen Arntson – Seattle Janine Burkhardt – Seattle Safety Officer Peter Clitherow – Seattle Brent Colvin – Everett Suzy Diesen – Kitsap Safety Officer Steve Glenn – Bellingham Safety Officer N. Michael Hansen – Seattle Steve Kleine – Tacoma Dick Lambe – Foothills Safety Officer Geoff Lawrence – Properties Safety Officer Rich Leggett – Seattle Amy Mann – Tacoma Miriam Marcus-Smith – Seattle Jim Nelson – Seattle John Ohlson – Seattle Chad Painter – Tacoma Safety Officer Tom Pearson – Olympia Safety Officer Jeff Panza – Seattle James Pierson – Bellingham Mark Scheffer – Seattle Damien Scott – Everett Dave Shema – Seattle Mike Sweeney – Seattle Tony Tsuboi – Everett Safety Officer Mike Waiss – Tacoma Jud Webb – Tacoma 1 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Summary Statistics ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Major Incidents (Emergency Medical Attention; Search and Rescue or 911 call and search performed) ... 8 January 19, 2013 – Stevens Lodge (Properties) ........................................................................................ 8 April 7, 2013 - Green River Headworks (Whitewater kayak outing) ......................................................... 8 April 20, 2013 -

The Following Were Collected by Carlos R

United States Department of Agriculture Plant Inventory Agricultural Research Service No. 217 Plant Materials Introduced in 2008 (Nos. 652416 - 655520) Foreword Plant Inventory No. 217 is the official listing of plant materials accepted into the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) between January 1 and December 31, 2008 and includes PI 652416 to PI 655520. The NPGS is managed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service (ARS). The information on each accession is essentially the information provided with the plant material when it was obtained by the NPGS. The information on an accession in the NPGS database may change as additional knowledge is obtained. The Germplasm Resources Information Network (http://www.ars-grin.gov/npgs/index.html) is the database for the NPGS and should be consulted for the current accession and evaluation information and to request germplasm. While the USDA/ARS attempts to maintain accurate information on all NPGS accessions, it is not responsible for the quality of the information it has been provided. For questions about this volume, contact the USDA/ARS/National Germplasm Resources Laboratory/Database Management Unit: [email protected] The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in its programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs and marital or familial status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact the USDA Office of Communications at (202) 720-2791. To file a complaint, write the Secretary of Agriculture, U.S. -

Area Notes 1999 EDITED by JOSE LUIS BERMUDEZ

Area Notes 1999 EDITED BY JOSE LUIS BERMUDEZ Alps and Pyrenees Lindsay Griffin Russia and Central Asia Paul Knott Greenland Derek Fordham Scottish Winter Simon Richardson India Harish Kapadia Pakistan Lindsay Griffin & David Hamilton Nepal Bill O'Connor North America Paul Hortonl American Alpine Journal LINDSAY GRIFFIN Alps and Pyrenees 1998 .. 1999 This report looks at selected activity, both in terms of exploration and technical performance, during the winter of 1998-99 and the following spring to autumn season. In preparing these notes Lindsay Griffin would like to acknowledge the assistance of Valeri Babanov, Julian Cartwright, Andy Cave, Lucian Comoy, Liana Darenskaya, Igor Koller, Mireille Lazarevitch, Ian Parnell, Emanuele Pellizzari, Michel Piola, AI Powell, Joan Quintana, Simon Richardson, Hilary Sharp, Thomas Tivadar, Mark Twight and Paolo Vitali. Technical grades are either French or UIAA unless otherwise stated. New route descriptions, corrections and any information on AC members' activities are most welcome and should be sent either to the Club or directly to: 2 Top Sling, Tregarth, Bangor, Gwynedd LI;S7 4RL. WINTER 1998-1999 The winterI spring season was noted for the big storm towards the end of January that killed the talented British climber, Jamie Fisher, on the summit ridge of Les Droites; the almost unprecedented snowfalls that at one stage marooned a reported 100,000 skiers at over 100 resorts and caused catastrophic avalanches, notably the one that wiped out much of the village of Montroc (12 people killed) above Argentiere and a second, which caused the deaths of 38 inhabitants in the Austrian village, Galtiir; and for the mid-March accident and subsequent fire that closed the Mont Blanc Tunnel (with still no sign of it reopening at the 213 214 THE ALPINE JOURNAL 2000 time of writing) and subsequently a similar accident closing the Tauern Tunnel in Austria. -

Empowering a Generation of Climbers My First Ascent an Epic Climb of Mt

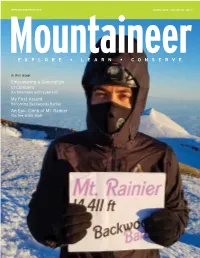

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG SPRING 2018 • VOLUME 112 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE in this issue: Empowering a Generation of Climbers An Interview with Lynn Hill My First Ascent Becoming Backwoods Barbie An Epic Climb of Mt. Rainier Via the Willis Wall tableofcontents Spring 2018 » Volume 112 » Number 2 Features The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy 24 Empowering a Generation of Climbers the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. An Interview with Lynn Hill 26 My First Ascent Becoming Backwoods Barbie 32 An Epic Climb of Mt. Rainier Via the Willis Wall Columns 7 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Marcey Kosman 8 VOICES HEARD 24 1000 Words: The Worth of a Picture 11 PEAK FITNESS Developing a Personal Program 12 BOOKMARKS Fuel Up on Real Food 14 OUTSIDE INSIGHT A Life of Adventure Education 16 YOUTH OUTSIDE We’ve Got Gear for You 18 SECRET RAINIER 26 Goat Island Mountain 20 TRAIL TALK The Trail Less Traveled 22 CONSERVATION CURRENTS Climbers Wanted: Liberty Bell Needs Help 37 IMPACT GIVING Make the Most of Your Mountaineers Donation 38 RETRO REWIND To Everest and Beyond 41 GLOBAL ADVENTURES The Extreme Fishermen of Portugal’s Rota Vicentina 55 LAST WORD Empowerment 32 Discover The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining, or have joined and aren’t sure where to star, why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the Mountaineer uses: Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of CLEAR informational meetings at each of our seven branches. on the cover: Bam Mendiola, AKA “Backwoods Barbie” stands on the top of Mount Rainier. -

JANUARY MEETING Thursday, January 5Th, 7:30 P.M

JANUARY 1989 BOEING EMPLOYEES ALPINE SOCIETY, INC. PresideW;~,.,., ... Ken Johnson .. OU·31 .. 342-3974 Conservation ........ Eric Kasiulis.. 81-16 .. 773-57 42 Vice Pr~llnt;. .... .steveMason.. 97 -1.7 ...237 -5820 Echo Editor......... .Rob Freeman .. 6N -95 ..234-0468 Treas=.......... EIden Altiz.er .. 97-17 ...234'1721 Equipm~nt ........... Gareth Beale .. 7A-35 .. 865-5375 Secre~_ .. , .. _.. _•• JolinSumner.• 2.6-63 ... 655~9882 Librarian ............ Rik Anderson .. 76-15 .. 237 -9645 Past Pmsident..A:mbrose. Bittner.. OT-06 ... 342-5140 Membership.. Richard Babunovic.. 6L-15 .. 235-7085 ·Aeti,:tilts ..........MelissaStorey .. 1R-40... 633-3730 Programs.......... Tim .Backman . .4M-02.. 655-4502 Photo: Nevado Huandoy by Mark Dale D. OTT 5K-25 * FROM: 6L-15 R_BABUNOVIC JANUARY MEETING Thursday, January 5th, 7:30 P.M. Oxbow Rec Center CROSS COUNTRY SKI ROUTES ON MT. HOOD AND CENTRAL OREGON The January meeting will feature a slide presentation by Klindt vielbig, mountaineer as well as skier and author of "Cross Country Ski Routes Of Oregons' Cascades". Klindt will show slides illustrating many of the tours described in his book including Mt. )iood, the Wallowa Mtns., Crater Lake, Broken Top Crater, and Mt. Shasta. The diversity of ski tours makes this program a great aid in learning more about oregon skiing. Additionally, Boealps member Jim Blilie will give a short ~esentation on ice climbing. This is an appetizer to Jim's Feb.4-5 Leavenworth ice climbing/knuckle bashing weekend extravaganza. Belay Stance Well November's powder has yielded to December's thaw. Where has all the snow gone. What had started as a great ski season is now looking somewhat questionable.