Alpine Courses Instruction Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Chamonix Ist Alles Ein Bisschen Höher Als Anderswo in Den Alpen

CHAMONIX DESTINATION 60 N Hohe 9 61 O O 9 9 Schule N Berge, Preise, Gefühle: In Chamonix ist alles ein bisschen höher als anderswo in den Alpen. Auf engem Raum hält das Mont-Blanc-Massiv alle Prüfungen bereit, denen sich ein Alpinist stellen kann. RALF!GANTZHORN erzählt, wie er nach Jahren des Büffelns das Alpin-Abitur doch noch absolviert hat. TEXT UND FOTOS: RALF GANTZHORN ALTE SCHULE Fritz Miller hat das große Orientierungs- Los gezogen und überprüft, ganz klassisch mit Kopie und Karte, Theorie und Praxis am Innominata-Grat. ALLMOUNTAIN DESTINATION Man kann es drehen und wenden wie tige Pracht final niederreißen. Tour man möchte, an Chamonix kommt man Ronde Nordwand – praktisch eisfrei. Zu- stieg zum Bivouac de la Fourche – nur nicht vorbei. Nirgendwo sonst auf dem noch durch Schutt möglich. „Schweizer- Planeten stehen so viele Berge, Spitzen, führe“ am Grand Capucin – der Berg- schrund wird sich kaum überwinden Türme und Nadeln von Weltruf, in lassen. Als Führerautor möchte man in keiner anderen Bergregion reiht sich auf so einem Moment verzweifeln. Seit fünf Jahren arbeite ich an einer Auswahl der so engem Raum eine Sehnsuchtstour an lohnendsten Touren im Südwesten des die nächste. Nicht zufällig also haben Alpenbogens. Und jetzt das! sich der Mont Blanc und seine Trabanten DIE!VERTE"!DAS!ALPIN-ABI zum weltweiten Mekka für Alpinisten Ein Jahr später sieht alles ganz anders aus. Der Winter 2017/2018 war endlich entwickelt. Chamonix quillt sommers mal wieder ein schneereicher. Die In- wie winters aus allen Nähten, ternetforen quollen über vor erfolgrei- chen Tourenberichten. Beste Verhält- Bergsteiger aus aller Welt bevölkern nisse am Walkerpfeiler; Innominata- Dorf und Granit oben drüber. -

Climbing the Sea Annual Report

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MARCH/APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 109 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE Annual Report 2014 PAGE 3 Climbing the Sea sailing PAGE 23 tableofcontents Mar/Apr 2015 » Volume 109 » Number 2 The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Features 3 Breakthrough The Mountaineers Annual Report 2014 23 Climbing the Sea a sailing experience 28 Sea Kayaking 23 a sport for everyone 30 National Trails Day celebrating the trails we love Columns 22 SUMMIT Savvy Guess that peak 29 MEMbER HIGHLIGHT Masako Nair 32 Nature’S WAy Western Bluebirds 34 RETRO REWIND Fred Beckey 36 PEAK FITNESS 30 Back-to-Backs Discover The Mountaineers Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the as a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of nonprofit organizations. informational meetings at each of our seven branches. Mountaineer uses: CLEAR on the cover: Lori Stamper learning to sail. Sailing story on page 23. photographer: Alan Vogt AREA 2 the mountaineer magazine mar/apr 2015 THE MOUNTAINEERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT Without individuals who appreciate the natural world and actively champion its preservation, we wouldn’t have the nearly 110 million acres of wilderness areas that we enjoy today. -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

Vocabulaire D'escalade Climbing Terms

VOCABULAIRE D'ESCALADE CLIMBING TERMS A - Assurer : To belay Assurer un grimpeur en tête ou en moulinette (To secure a climber) - Assureur : Belayer Personne qui assure un grimpeur (The person securing the climber) - "Avale" / "Sec"/ "Bloque" : "Tight rope" / "Take" Le premier de cordée (ou le second) demande à l'assureur de prendre le mou de la corde (Yelled by the leader or the follower when she/he wants a tighter belay) B - Bac / Baquet : Bucket, Jug Très bonne prise (A large hold) - Baudrier / Baudard : Harness Harnais d'escalade - Bloc : Bouldering, to boulder Escalade de blocs, faire du bloc (Climbing unroped on boulders in Fontainebleau for exemple) C - Casque : Helmet Protection de la tête contre les chutes de pierres... (Protect the head from falling stones...) - Chaussons d'escalade : Climbing shoes Chaussons ou ballerines pourvus d'une gomme très adhérente (Shoes made of sticky rubber) - Corde : Rope - Cotation : Grade Degré de difficulté d'une voie, d'un bloc... (Technical difficulty of the routes, boulders...) - Crux : Crux Le passage délicat dans une voie, le pas de la voie (The hard bit) D - Dalle : Slab Voie ou bloc généralement plat où l'on grimpe en adhérence ou sur grattons (Flat and seemingly featureless, not quite vertical piece of rock) - Daubé / Avoir les bouteilles : Pumped Avoir les avants-bras explosés, ne plus rien sentir... (The felling of overworked muscles) - Dégaine : Quickdraw, quick Deux mousquetons reliés par une sangle (Short sling with karabiners on either side) - Descendeur :Descender Appareil utilisé -

Tacoma Intermediate Snow Skills Curriculum 2019

Tacoma Intermediate Snow Skills Curriculum 2019 Purpose: Build competent basic glacier rope leaders ● Ensure Intermediate student understanding and knowledge of basic skills/topics so they may adequately teach basic students ● Build on student knowledge of basic skills: ○ Critical thinking through the steps of crevasse rescue and the haul systems ○ Snow anchors ○ Snow belays ● Discuss circumstances and decision making on a glacier climb ● Start introducing 2 person team travel ● Building the community - Have a good time and give the students a chance to get to know each other. Required Reading: Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, 9th Edition, Chapter 3 - Camping, Food, and Water Chapter 16 - Snow Travel and Climbing Chapter 17 - Avalanche Safety Chapter 18 - Glacier Travel and Crevasse Rescue Chapter 27 - The Cycle of Snow Snow Anchors for Belaying and Rescue. D. Bogie, A. Fortini. Backing up an Anchor for Crevasse Rescue. L. Goldie. Self Arrest with Crampons. J. Martin. Drop Loop Crevasse Rescue by Gregg Gagliardi Crevasse rescue videos by AMGA instructor Jeff Ward: ● How to Rope Up for Glacier Travel ● How to Transfer a Fallen Climber's Weight to a Snow Anchor for Crevasse Rescue ● How to Back Up a Snow Anchor for Crevasse Rescue ● How to Rappel Into and Ascend Out of a Crevasse ● How to Prepare a Crevasse Lip for Rescue ● How to Haul a Climber Out of a Crevasse Recommended Reading: Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain, 2nd edition. Bruce Tremper, ISBN 1594850844 Snow Sense. J.Fredston and D.Fester, ISBN 0964399407 Snow Travel: Skills for Climbing, Hiking, and Moving Over Snow. M. Zawaski. General design principles 1. -

Final Report Fhwa-Wy-09/05F Snow Supporting

FINAL REPORT FHWA-WY-09/05F State of Wyoming U.S. Department of Transportation Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration SNOW SUPPORTING STRUCTURES FOR AVALANCHE HAZARD REDUCTION, 151 AVALANCHE, HIGHWAY US 89/191, JACKSON, WYOMING By: InterAlpine Associates 83 El Camino Tesoros Sedona, Arizona 86336 April 2009 Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author(s) who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Wyoming Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The United States Government and the State of Wyoming do not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objectives of the document. Quality Assurance Statement The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Technical Report Documentation Page Report No. Government Accession No. Recipients Catalog No. FHWA-WY-09/05F Report Date Title and Subtitle April 2009 Snow Supporting Structures for Avalanche Hazard Reduction, 151 Avalanche, US 89/191, Jackson, Wyoming Performing Organization Code Author(s): Rand Decker; Joshua Hewes; Scotts Merry; Perry Wood Performing Organization Report No. -

Where Snow Is a Landmark: Route Direction Elements in Alpine Contexts

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Bangor University: eBangor / Prifysgol Bangor Where Snow is a Landmark: Route Direction Elements in Alpine Contexts Ekaterina Egorova1,2, Thora Tenbrink3, Ross S. Purves1 1 Department of Geography, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland {ekaterina.egorova,ross.purves}@geo.uzh.ch 2 University Priority Research Programme Language and Space (URPP SpuR), University of Zurich, Switzerland 3 School of Linguistics and English Language, Bangor University, Bangor, UK [email protected] Abstract. Route directions research has mostly focused on urban space so far, highlighting human concepts of street networks based on a range of recurring elements such as route segments, decision points, landmarks and actions. We explored the way route directions reflect the features of space and activity in the context of mountaineering. Alpine route directions are only rarely segmented through decision points related to reorientation; instead, segmentation is based on changing topography. Segments are described with various degrees of detail, depending on difficulty. For landmark description, direction givers refer to properties such as type of surface, dimension, colour of landscape features; ter- rain properties (such as snow) can also serve as landmarks. Action descriptions reflect the geometrical conceptualization of landscape features and dimension- ality of space. Further, they are very rich in the semantics of manner of motion. Keywords: route directions ∙ natural environment ∙ segmentation ∙ landmark ∙ mountaineering ∙ 1 Introduction In 1995, Max Egenhofer and David Mark proposed the notion of Naive Geography for the body of knowledge that lay people have about the surrounding geographic world [15] as a counterpart to the formalizations used by professional geographic community. -

Reviving We Can't Hear a Historical Race That Hasn't Been Run How to Take in Over 70 Years Great Action Shots Like the One on This Cover Tableofcontents

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2014 • VOLUME 108 • NO. 1 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE exciting and unpredictable mixed climbing mentoring women in the lead listening to animals reviving we can't hear a historical race that hasn't been run how to take in over 70 years great action shots like the one on this cover tableofcontents Jan/Feb 2014 » Volume 108 » Number 1 Enriching the community by helping people explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. 14 Mountaineers to the Rescue The Pierce County Red Cross honors six Mountaineers 18 Beauty of Unpredictability An interview with mixed-climber Roger Strong 22 Women in the Lead 10 An all-female climbing mentor group led by Stef Schiller 23 Have Camera Will Capture Mike Warren discusses his outdoor photography tricks 6 DONOR HIGHLIGHT Bill Hecker with a vision of world-class climbing 7 Impact GIVING The plan to add friction slabs 8 OUTDOOR Education Sisters of Adventure by Carolyn and Isabelle Stratford 10 Conservation currents 18 The importance and conservation of bees 12 nature'S waY Experts on sound, from underwater to extinction 16 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Nina Crampton and her 10 essential answers 28 RETRO rewinD The Patrol Race is back after over 70 years 23 DiscOVER THE MOuntaineers Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining—or have joined and aren’t sure where to Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates start—why not set a date to Meet The Mountainers? Check the as a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various Branching Out section of the magazine (page 32) for times and nonprofit organizations. -

View from the Summit Over the Italian Side of Mont Blanc Is Breathtaking! Descent Via Normal Route

Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix 190 place de l’église - 74400 Chamonix – France - Tél : + 33 (0)4 50 53 00 88 www.chamonix-guides.com - e-mail : [email protected] AIGUILLE VERTE - PRIVE - TISON Duration: 5 days Level: Price from: 2 485 € The Chamonix Compagnie des Guides offers you a collection of programmes to climb the legendary peaks of the Alps. We have selected a route together with a specific preparatory package for each peak. Each route chosen is universally recognised as unmissable. Thanks to our unique centre of expertise, we can also guide you on other routes. So don’t hesitate to dream big, as our expertise is at your service to help you make your dreams come true. The Aiguille Verte is THE legendary peak in the Mont Blanc Massif. The celebrated mountaineer and writer Gaston Rébuffat contributed significantly to this reputation when he said of it: “Before the Verte one is a mountaineer, on the Verte one becomes a ‘Montagnard’ (mountain dweller)”. It is certainly true that there are no easy routes on this peak and each face is a significant challenge. The south side of the Aiguille Verte is an outstanding snow route that follows the Whymper Couloir for over 700 metres. This is unquestionably one of the most beautiful routes in the massif, and we offer a four-day programme for its ascent. ITINERARY Day 1 and Day 2 : Acclimatisation routes with a night in the Torino Hut (3370m) These first two days give your body the essential time it requires to adapt to altitude. -

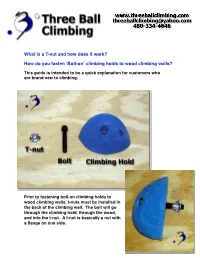

What Is a T-Nut and How Does It Work? How Do You Fasten ʻbolt-Onʼ

What is a T-nut and how does it work? How do you fasten ʻBolt-onʼ climbing holds to wood climbing walls? This guide is intended to be a quick explanation for customers who are brand new to climbing. Prior to fastening bolt-on climbing holds to wood climbing walls, t-nuts must be installed in the back of the climbing wall. The bolt will go through the climbing hold, through the wood, and into the t-nut. A t-nut is basically a nut with a flange on one side. The barrel of the t-nut can fit into a 7/16” hole, but the flange is 1” wide so it cannot fit through the hole. The flange catches the surface of the climbing wall surrounding the 7/16” hole. The Barrel of the T-nut should be recessed behind the front surface of the climbing wall by at least 1/ 4”. Climbing holds must not make di- rect contact with the t-nut. If the climbing hold makes direct con- tact with the t-nut it will eliminate the friction between the surface of the climbing wall and the back of the climbing hold. Climbing holds must have good contact with the climbing wall in order to be secure. Selecting the proper length bolts: Every climbing hold has a different shape and structure. Because of these variations, the depth of the bolt hole varies from one climbing hold to another. Frogs 20 Pack Example: The 20 pack of Frogs Jugs to the right consists of several different shaped grips. -

Ten Years of Winter: the Cold Decade and Environmental

TEN YEARS OF WINTER: THE COLD DECADE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE EARLY 19 TH CENTURY by MICHAEL SEAN MUNGER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Michael Sean Munger Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of History by: Matthew Dennis Chair Lindsay Braun Core Member Marsha Weisiger Core Member Mark Carey Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Michael Sean Munger iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Michael Sean Munger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History June 2017 Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century Two volcanic eruptions in 1809 and 1815 shrouded the earth in sulfur dioxide and triggered a series of weather and climate anomalies manifesting themselves between 1810 and 1819, a period that scientists have termed the “Cold Decade.” People who lived during the Cold Decade appreciated its anomalies through direct experience, and they employed a number of cognitive and analytical tools to try to construct the environmental worlds in which they lived. Environmental consciousness in the early 19 th century commonly operated on two interrelated layers. -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue.